Archive for April, 2011

Public Pensions and Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on April 29th, 2011

In a couple of previous posts, I’ve discussed the folly of using a loophole in public pension accounting to increase the discount rate by taking on added risk. Naturally, that fear would be more justified if it turned out that public pensions were doing that. Herewith, the evidence.

The Census Bureau does an annual survey of the state of public pensions, although they tend to take their sweet time posting the data. (The most recent data available was for FY2008.) Since the time when online records begin, in 1993, until 2008, you can see some obvious trends in public pension funds’ asset allocation:

The proportion in US stocks had risen almost 5 percentage points, from 34% to 39%, and the amount in safer, but really boring Treasuries has dropped from almost 20% to just under 5%. You can see where the poor years for stocks in 2007 and 2008 took back some of their gains, but inasmuch as the fund managers should have been rebalancing, this hardly vindicates them.

The fund managers have also been risking more of their money; cash and liquid securities dropped from about 7.5% to under 3%, although that could be for a number of reasons. The pension operations could be efficient, for instance, or the managers may have had better actuarial data at their disposal. In what looks like a gap in the Census survey questionnaire, “Other” is up significantly, from 5% in 1994 to 13% in 2008. Anything that’s 1/8 of your investment portfolio shouldn’t really be lumped together as “Other.”

And since its introduction as a separate category in 2002, Foreign Investments (not shown) have risen from 12% to about 15%. That’s probably a result of both better returns and increased investment.

I also want to emphasize that this is aggregate data for State & Local pensions across the US, not just for PERA. CalPers may well distort the data, and some plans, like DERP, are around 90% funded and suffered very little in the stock downturn in terms of fundedness.

In any event, what is clear is that the instruments best-suited to stable, long-term returns (at least up until now), US Treasuries have either been sold off or allowed to mature, with the funds being put into US stocks and some other, almost certainly riskier, categories.

There’s a lot more data over at the Census site, including some state-only data over the last 3 years that also has actuarials associated with it, so I’m hoping to make some time to dig into that, as well, but as usual, no promises.

Keeping the Higher Ed Bubble Inflated

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Education, PPC on April 28th, 2011

UPDATE: I am advised that this was the closest vote in 20 years on a tuition increase: 5-4. I don’t have the names of those who had the courage to vote No, but kudos to them for doing so. Even though Regents are elected, it’s relatively easy for them to roll over to an appointed administration on tuition votes, especially given the (at least perceived) centrality of higher education to opportunity for advancement.

The CU Regents have approved a 9.3% tuition increase for in-state students, and a 3% increase for out-of-state students. No doubt it’ll take special scientific instruments to measure the time that elapsed between this announcement and certain legislators’ bemoaning the fact that we “don’t fund higher ed.” But higher ed, even here in Colorado, has done a pretty terrible job of accounting exactly what it is we’re supposed to be funding.

The core mission of the university is the education of students, culminating in a degree that is supposed to represent the mastery of the material. It is almost impossible to get a straight answer as to what that actually costs. Go to the CU website, and you’ll be provided with a wealth of information about their sources of funding. Detailed information about spending is almost impossible to find.

Petraeus-Panetta Pavane Pensees

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Defense, National Politics, PPC on April 27th, 2011

My first reaction is that this is good for Obama, politically, bad for Afghanistan, as good for defense as can be expected, and bad for Petraeus. (The CIA being impervious to reform, hardly rates a good-bad mention.)

Bad for Petraeus: He probably was exhausted after close to 10 years in the field, but he should have been JCS Chief. True, working in counter-insurgency requires a lot of facility with operational intelligence, so it’s not completely a fish out of water. But the CIA does much more well-hedged intelligence “analysis,” most of it bad, than it does actual intelligence-gathering and use. Petraeus has directed the war in two theaters, and deserves a chance to apply what he’s learned to the military as a whole. It’s hard to escape the thought that Obama is sidelining someone he’s afraid of politically, even though Petraeus has repeatedly disavowed political ambition. That’s why it’s

Good for Obama Politically: He can put a purported rival in a position to fail (who was the last actually successful DCI?), keep him from speaking with authority as he spends energy navigating a bureaucratic and political jungle. Panetta will probably be at home (enough) in Defense, and will be on the President’s side there.

Good for Defense: At least in terms of not having an empty suit or someone likely to wreck the place or take on unnecessary fights. Panetta’s not a fool, but he was in over his head at CIA. His job will be to manage the Carter-like hollowing-out of DoD, which Obama’s successor will have to fix. But he’s unlikely to roll over completely, and will at least bring an outsider’s eye to the job.

Let The Narrative Define The Candidate

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Colorado Politics, National Politics, PPC on April 27th, 2011

Very quickly, the flagship Ricochet podcast has joined my favorite weekly listening. A couple of weeks ago, Pat Caddell was the guest, and as usual, the pragmatic, tell-it-like-he-sees it Democrat pollster was a font of helpful advice for Republicans, all of which is worth listening to. This particular bit stuck out: he suggested that the Republicans need to settle on a narrative first, and then the proper candidate will rise to the narrative. It’s an interesting thought, and one worth considering.

His strategic advice is predicated on the notion – facts, really – that time is shorter than we think, and that the narrative for the election will be set this year, not next. I think he’s probably right on this. People’s opinions on Obama – and presidential re-elections are always first about the incumbent – are already being cemented, and the cement is starting to cure. You see it in the “who do you trust more on X issue?” polling, on the right-track/wrong-track question, on a general atmosphere of incompetence and disconnect.

The Dems and the MSM (but I repeat myself) will try their hardest to shape the narrative this year to their advantage. You see this in the stepped-up union activity, the attempt to frame the budget fight. How both Wisconsin and the debt ceiling/budget fight play out, along with the continuing court battles over Obamacare (are you listening, Rep Stephens?) will be major factors in how these impressions solidify. The specific issues, and the framing of those issues as “budget-cutting” vs. “growth-enhancing,” as an example, will also make a huge difference. And even if we don’t know what particular economic or foreign policy details will be on people’s minds in 2012, the right narrative can absorb a wide variety of specifics and surprises.

By deciding on the narrative first, we determine the basis on which we’ll fight the election, we set out priorities and a vision of what’s right and wrong for the country, and where we want to lead it and see it led.

Last Days of Passover

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on April 24th, 2011

Sounds apocalyptic, no? Well, it’s just that Passover has non-work days at the beginning and at the end, so I won’t be posting Monday, or Tuesday during the day.

See you on the other side.

Everybody Likes A Good Discount

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on April 24th, 2011

So with all the discussion about PERA, one key aspect of pension accounting hasn’t yet been mentioned: the discount rate. Now before you go all accounting-comatose on me, understand how important this is. Because with all the talk of how underfunded PERA is, it’s actually even more underfunded than you think.

Basically, if you have an obligation to meet, the discount rate is the rate you use to see how much money you need to have now in order to meet that obligation. So if you’re going to have to make good on a $100,000 obligation 10 years from now, and you use a 4.5% discount rate, you need to have about $65,000 now. If you use an 8% discount rate, you only need about $46,000.

Of course, the discount rate isn’t arbitrary. It represents a concept. The discount rate is the required rate of return, the return that an investor in that project requires, given the level of risk that he’s taking on.

The problem here, and how this relates to PERA (and many, many other public pensions), is that PERA is using the wrong discount rate. Instead of using the 4.5% discount rate, they’re using the 8% discount rate, which makes them look even less underfunded than they are.

PERA – Why 8% Isn’t 8%

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on April 22nd, 2011

State Treasurer Walker Stapleton has been on the hustings, touting the need for PERA reform. His oped in the Denver Post a little while ago pointed out that the fund’s actuaries assume an 8% return on investments. If we don’t do something about the underfunding, Stapleton noted, we’ll be forced to take on more risk to try to reach the fund’s investment goals.

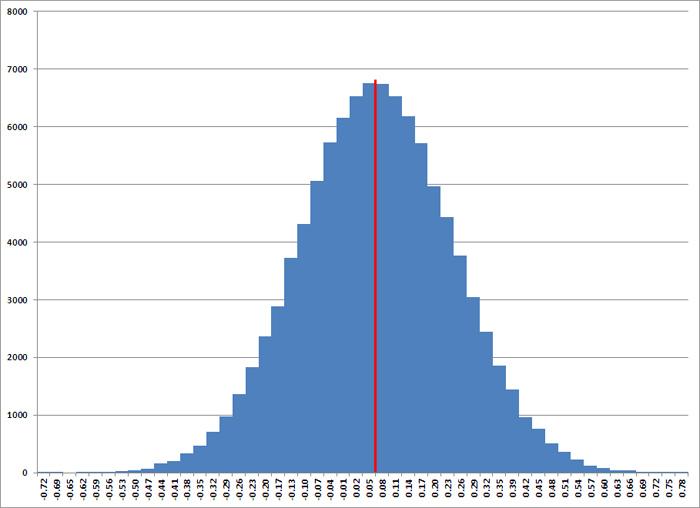

Now, PERA’s been criticized for assuming an 8% return, but that’s not really the problem. Eight percent is, in fact, the average annual return on US stocks since about 1870, according to data collected by Robert Shiller, he of the half-eponymous Case-Shiller Housing Index. The problem is, the standard deviation – the range within which about 5/8 of the returns actually fall – is 18%:

Which means that a lot of the time – almost one-third – you’re getting negative returns. For Backbone Business, I worked up a little scenario where you’re starting with $100,000, paying out certain portion each year, getting 8% return a year on your balance, and you come out even. But what should be apparent is that there are lots of scenarios that get you 8% average return, but force you to pay out more than you’re getting in the early years, and you never make up the difference. Here are some very basic scenarios:

And the graphs of the balances:

Atlas Shrugged and the Railroads

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on April 22nd, 2011

Interestingly, one of the complaints that conservatives have about Atlas Shrugged is that the movie centers around a railroad. (McClatchy, too, but then, they’ll believe – or not – pretty much anything.) For some reason, they have a hard time believing that people will, or do, actually use railroads.

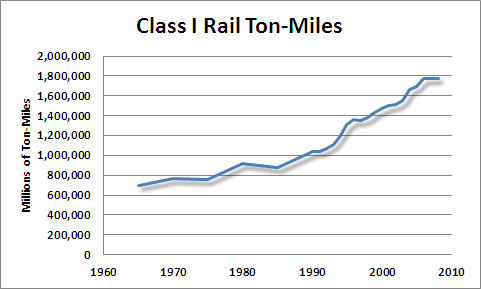

In fact, rail is increasingly important for freight, and has been on the upswing for a couple of decades now. Take a look at these following charts derived from Bureau of Transportation Statistics data. Overall Class I (major trunk line) ton-mileage stalled in the 70s, but started upward again with deregulation and the welcome death of the Interstate Commerce Commission:

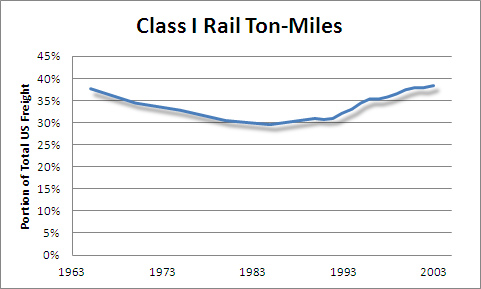

And as a percentage of total US freight ton-miles, it’s been headed up since the mid-80s:

About a year and a half ago, the Federal Railroad Administration published a report indicating that over long distances, rail is between 2-5.5x more efficient than trucking (Hat Tip: Future Pundit). I work at a trucking company, and I can tell you that intermodal – combined truck-train for long-haul shipments – is growing by leaps and bounds. Given the massive investment necessary to lay new track and secure new rolling stock, trucks continue to be a better choice for short-haul. But the best coast-to-coast operational choice seems to be rounding up the freight onto a container by truck, getting it to the railhead, and letting the train do the long-haul work. Trucks can then do the local or regional delivery at the other end. I even heard on long-time trucker complaining about this trend in the company cafeteria a few weeks ago.

I can’t remember where I saw it, but someone also poke fun at the idea of transporting oil by train. Hadn’t these people ever heard of pipelines? Aside from the apparent permitting nightmare in getting new pipelines approved, I can also tell you that the idea isn’t necessarily as ridiculous as it sounds. When were were looking at a couple of different ethanol plays at the brokerage, the need for specialized railcars was one of the drivers we took into consideration.

I initially also had thought that maybe it would have been better to focus on some newer technology rather than trains, but having seen the film, I’ve no doubt they made the right choice. Trains are visible, tangible, and connect with something very American.

The interesting thing about O’Rourke’s suggestion – that maybe they would have been better off setting the film in the 1950s – is that instead of liberating the filmmakers, it would have firmly trapped the film in past, reducing its relevance even more. Because almost everything Rand projected about trains actually happened. Unable to compete with subsidized roads, regulated to death by the ICC, trains deferred more and more maintenance, until northeast corridor rail freight virtually collapsed in the late 60s, leading to an actual government takeover and the creation of Conrail and Amtrak.

Once railroads were able to set their own rates again, they consolidated and recovered. Conrail’s operations have since been privatized, and the graphs above show the results. Union Pacific has been profitable right through the recession.

Railroads, as mentioned, do have a problem with the large capital investment necessary to expand, making them less flexible compared to trucks, just as light rail or commuter rail is less flexible compared to buses. But the idea that the country neither needs nor uses railroads just isn’t true, and fuel costs – as indicated in the film – will just make them more relevant for long-haul trips.

Solar Assumptions

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC on April 20th, 2011

Some of my favorite listening is to Stanford’s Entrepreneur’s Corner. It seems to be guest lecturers to one of Stanford B-school classes, and they’re almost always entrepreneurs who’ve made good, coming back to share their wisdom. (The lectures tend to be entertaining, in Guy Kawasaki’s case, highly so.)

One of the recent lectures is by a fellow named Bill Gross, who’s founded a large number of companies, but is best known for eSolar and and Idealab. How he created Idealab, and turned it into a machine for generating ideas and exploring the interesting ones, while generating profit and not causing people to fear losing their jobs, is fascinating in itself. It bespeaks a willingness to think outside the normal managerial box, and a love of play, which is often missing in business. I think I’d like working for Bill Gross.

Unfortunately, he then turns to his other project, eSolar. Now, Gross doesn’t mention looking for government subsidies, although I haven’t researched how many of the solar farms he’s created benefit from them. But he freely admits that right now, on a per-unit-of-power-generated basis, solar cannot compete with oil. His thesis is, of course, that growing third-world economies are going to need power, too, and that there just isn’t enough oil or gas to power them through the next century.

Gross claims that solar is perfectly suited to the task, because unlike fossil fuels and wind, it’s evenly (democratically, in his word) distributed. And then he asks the really cool question: how can we apply a law we know: Moore’s Law, the progressive advance in computing power, to solar? He’s developed a means of closely coordinating the mirrors in a large solar-concentrator array, using microprocessors that help the mirrors tightly track the sun throughout the day, something that would have been prohibitively expensive only a few years ago. It’s very clever, really. Using these assumptions, he makes a compelling case for the long-term competitiveness of solar vs. fossil-fuels, without assuming huge runups in the cost of gas.

But I think his assumptions are flawed. First, solar power is decidedly not uniformly distributed. Colorado has 300 days or so of sunlight. Germany and Japan, solar leaders by virtue of massive (and since revoked) government subsidy, have far less sunlight. It’s not just climate, either. The farther you are away from the equator, the less sunlight you have on average, because the sun’s rays come in at a shallower angle during half the year. Even during summer, I wouldn’t want to rely on solar in Alaska.

He also puts his thumb on the scale in a more subtle way. Other energy sources can also inventively use computing power, both in their production and their consumption. By denying them the benefits of Moore’s Law, he’s giving his idea an advantage it won’t enjoy in the real world.

He argues that wind has its place, but it’s not a very large place. He argues that nuclear can’t provide enough power, and here, I have to say, I find his numbers unconvincing. (He maintains that long lead times and the expenses involved in making nuclear safe limit the number of plants you can create. But demand will make supply profitable, and you can finish as many as you can start.) So while he’s willing to live with a suite of energy sources, he really believes in solar.

Unfortunately, I think he’s built too many assumptions into that belief.

Passover 5771

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Jewish on April 19th, 2011

So as Passover 5761 is here, a few thoughts, some old some new.

Passover commemorates, in effect, the birth of the Jewish people as a nation, as opposed to simply being a collection of tribes, or individuals descended from Jacob. The Haggadah is in a very real sense, the story that we as Jews, tell ourselves about ourselves. The Seder admonishes us to relive the Exodus as though it actually happened to us. And for anyone who becomes Jewish, it becomes their story, as well.

I know I’ve mentioned before that there’s a story in the Haggadah about five rabbis discussing the Exodus. All five rabbis are either converts, descended from converts, or in one case, a Levi (according to Jewish tradition, the members of the tribe of Levi weren’t forced into labor). So none of them actually had ancestors who were enslaved, yet all were allowed and encouraged to adopt, that story as their own.

I like to compare this to what we, as Americans do, every time a new round of immigrants is sworn in as citizens. Our story is now their story. The Declaration and the Constitution are my inheritance, even though my ancestors were stuck in eastern Europe and Russia at the time. It’s one of the reasons that I find Dennis Prager’s notion of an Independence Day Seder to be brilliant. (I’ve been asked to help design the program for one such seder this year; I’ll work on it with relish, but seriously, wish me luck.)

Michael Medved’s article about the “Preposterous Politics of Passover” in the current Commentary, seems to make a similar connection between freedom and the value of tradition and ritual:

Ironically, the Jewish festival that most explicitly emphasizes freedom and liberation simultaneously highlights the inescapable bonds of tradition—especially with a surprising 77 percent of American Jews reporting that they observe the holiday of Passover, according to the National Jewish Population Survey of 2003, more than any other form of religious participation.

It’s an article worth reading, a warning against the hijacking of sacred tradition for transient politics. I do have one objection, though. Medved mentions, but glosses over, “Christian” Seders, which I have to say, I do object to. It’s one thing to attend (or recreate) a Jewish ceremony for the purposes of better understanding the Jewish roots of Christianity, it’s something else entirely to appropriate a Jewish tradition, make the Jews disappear, and recast the symbolism as Christian. There’s Easter. There’s Passover. They are different and separate things, that embody different notions of man’s relationship to God and to the world.

That said, Medved makes a tour of the modern Haggadah. We always make it a point of getting at least one new Haggadah each year. We always get one with a traditional text, but with a commentary we don’t have yet. A couple of years ago, we got a compilation of Rav Soloveitchik’s commentaries on the Haggadah. This year, it was Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks.

Probably the wittiest Haggadah we have is the IDF Haggadah. On the night before the holiday starts, we’re obliged to do a “search for chametz,” or leavened bread. The Haggadah’s illustrative photograph is of an IDF unit examining a smuggling tunnel in Gaza.

(Written Monday evening, before the actual start of Passover, for those of you who are wondering.)