Posts Tagged Atlas Shrugged

How Would You Sell The Tea Party?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Movies, National Politics, PPC on March 22nd, 2012

Reading Malcolm Gladwell’s What the Dog Saw, I got to his essay, “True Colors: Hair Dye and the Hidden History of Postwar America.” He argues that the difference between Clairol’s “Does She or Doesn’t She?” and L’Oreal’s “Because I’m Worth It,” is the difference between 1950s and 1970s feminism. Moreover, even when the two product’s pitches had essentially merged (Gladwell was writing in 1999), their buyer’s different self-images lingered on. Smart ad men know they’re selling more than a product, they’re selling an experience, or an image. Sometimes, that image or dream ties into a larger social change or movement, and that that’s both a reflection and an agent of that change:

This notion of household products as psychological furniture is, when you think about it, a radical idea. When we give an account of how we got to where we are, we’re inclined to credit the philosophical over the physical, and the products of art over the products of commerce…

“Because I’m worth it,” and “Does she or doesn’t she?” were powerful, then, precisely because they were commercials, for commercials come with products attached, and products offer something that songs and poems and political movements and radical ideologies do not, which is an immediate and affordable means of transformation.

Far from trivializing a political, social, or economic movement, commercialization can help make it personal and accessible, and therefore less threatening and more familiar.

We’ve seen a couple of Tea Party movies, one explicitly so, (Atlas Shrugged), and one implicitly (Robin Hood). Thus far, I’m aware of only one commercial that implies a Tea Party presence, the Starbucks commercial with the angry old loner who yells at town halls, which would be a bit like L’Oreal selling “Because I’m worth it” using Nurse Ratchet or Gloria Steinem, who quickly became a caricature of herself.

It may be that we have to wait until the Tea Party sees more success, in winning hearts and minds if not yet national elections, before companies are willing to bet their products’ success on its messaging. But just as feminism succeeded in making the political personal (and more destructively, the personal political), and as environmentalism succeeded in making small actions and then products green, the Tea Party might get farther by doing something similar for its own themes.

It’s not wise to choose your political message based on the products it might sell, but certain themes will sell better than others. We can search forever in the tall grass of social history to discover how much of feminism’s public appeal was based on opportunity, and how much drew from raging against The Patriarchy, but there’s no question that positive sells. Ilon Specht may have been angry when she wrote, “Because I’m worth it,” but the slogan expresses liberation, not anger.

To be sure, it faces some hurdles in doing this. If the theme is fiscal responsibility, most families already need to spend less than they make. If it’s personal liberty, the government’s probably a tougher customer to disobeying rules, tougher than most companies. And to the extent that it dwells on what used to be, rather than what might be, its message is nostalgia, and the only products it will sell are baseball and Coca-Cola. You want to get people to invite your ideas into their homes, you need to be relevant to how they’re living their lives today, and want to be living them tomorrow.

So, what products do you see as being right for capturing the Tea Party ethos, and allowing people to internalize it? Which themes are best suited to commercialization? And what messages should go in their commercials? How would you write such a commercial?

Atlas Shrugged and the Railroads

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on April 22nd, 2011

Interestingly, one of the complaints that conservatives have about Atlas Shrugged is that the movie centers around a railroad. (McClatchy, too, but then, they’ll believe – or not – pretty much anything.) For some reason, they have a hard time believing that people will, or do, actually use railroads.

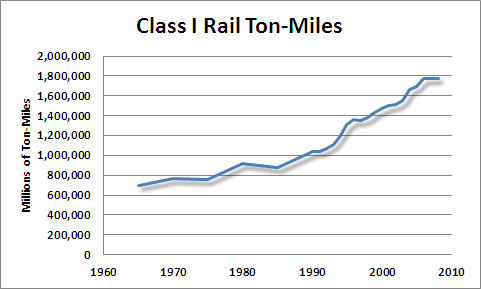

In fact, rail is increasingly important for freight, and has been on the upswing for a couple of decades now. Take a look at these following charts derived from Bureau of Transportation Statistics data. Overall Class I (major trunk line) ton-mileage stalled in the 70s, but started upward again with deregulation and the welcome death of the Interstate Commerce Commission:

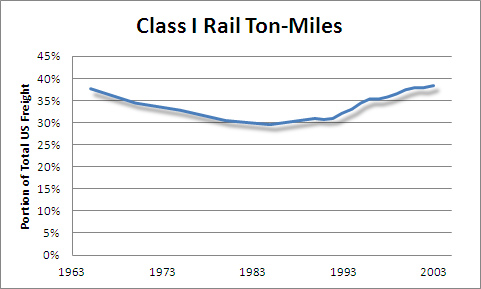

And as a percentage of total US freight ton-miles, it’s been headed up since the mid-80s:

About a year and a half ago, the Federal Railroad Administration published a report indicating that over long distances, rail is between 2-5.5x more efficient than trucking (Hat Tip: Future Pundit). I work at a trucking company, and I can tell you that intermodal – combined truck-train for long-haul shipments – is growing by leaps and bounds. Given the massive investment necessary to lay new track and secure new rolling stock, trucks continue to be a better choice for short-haul. But the best coast-to-coast operational choice seems to be rounding up the freight onto a container by truck, getting it to the railhead, and letting the train do the long-haul work. Trucks can then do the local or regional delivery at the other end. I even heard on long-time trucker complaining about this trend in the company cafeteria a few weeks ago.

I can’t remember where I saw it, but someone also poke fun at the idea of transporting oil by train. Hadn’t these people ever heard of pipelines? Aside from the apparent permitting nightmare in getting new pipelines approved, I can also tell you that the idea isn’t necessarily as ridiculous as it sounds. When were were looking at a couple of different ethanol plays at the brokerage, the need for specialized railcars was one of the drivers we took into consideration.

I initially also had thought that maybe it would have been better to focus on some newer technology rather than trains, but having seen the film, I’ve no doubt they made the right choice. Trains are visible, tangible, and connect with something very American.

The interesting thing about O’Rourke’s suggestion – that maybe they would have been better off setting the film in the 1950s – is that instead of liberating the filmmakers, it would have firmly trapped the film in past, reducing its relevance even more. Because almost everything Rand projected about trains actually happened. Unable to compete with subsidized roads, regulated to death by the ICC, trains deferred more and more maintenance, until northeast corridor rail freight virtually collapsed in the late 60s, leading to an actual government takeover and the creation of Conrail and Amtrak.

Once railroads were able to set their own rates again, they consolidated and recovered. Conrail’s operations have since been privatized, and the graphs above show the results. Union Pacific has been profitable right through the recession.

Railroads, as mentioned, do have a problem with the large capital investment necessary to expand, making them less flexible compared to trucks, just as light rail or commuter rail is less flexible compared to buses. But the idea that the country neither needs nor uses railroads just isn’t true, and fuel costs – as indicated in the film – will just make them more relevant for long-haul trips.

Atlas Shrugged – Part I

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Movies, PPC on April 18th, 2011

Susie and I went to go see Atlas Shrugged last night over at the Aurora 16. I’m not a big fan of saying something just to hear myself blog, so I’ll limit myself here to comments that I don’t think I’ve seen anywhere before.

The consensus – that the acting seemed good, the fidelity to the book about right, and that the writers picked the right parts to hold onto and the right portions to let go – seems about right to me. The budget – a mere $10 million, shot quickly to retain the rights – should also be kept in mind.

That said, the movie could have benefitted from slowing down in a couple of ways. Dagny’s entrance in the book – riding the train, taking control of a muddled situation on the line, musing about promoting Owen Kellogg – would have made the scene with Kellogg work better. It’s ok to make Midas Mulligan disappear after introducing him to a really pompous-sounding John Galt. We don’t need to know him, and we don’t know Galt. But Kellogg isn’t a Producer, he’s a potential producer who right now is just a competent guy. Dagny needs him because the line is falling apart all over the country, and that’s the only context in which we’re going to care about him either.

We’re told that American infrastructure is disintegrating into dust with footage from a train wreck and an opening scene that looks like it was pulled from the Kobe, Japan earthquake. A scene where Dagny has to basically take control of a side-tracked train would show it to us, which is what movies are supposed to do. I know $10 million doesn’t leave a lot for on-location shooting. One of the reviewers’ favorite complaints is that the move spends too much time with people talking in offices. But that’s true of all boardroom and courtroom dramas, including a couple of my favorites, Executive Suite, and Sabrina.

One complaint that I had about Atlas Shrugged the book is that I don’t think Rand really articulated what drives the Carnegies, Vanderbilts, and Fords to build. She has her stand-in for them, Hank Rearden say that his only purpose is to make money. I think this slightly misses the mark, that Arthur Brooks’s “earned success” is closer, and that making money is largely a by-product of that success. You’ll hear that from any number of wildly successful businessmen.

The movie actually captures this notion better than the book, in a brief scene where Rearden turns down an offer for the rights to his metal, “Because it’s mine,” in a way that the iron mines and foundries weren’t. Those were all managed by him, but his contribution is his metal.

Most reviewers will also allow their impatience with the subject matter to cloud their judgment about the movie as a whole. There’s almost nothing to be done about that. It’s an inherently political movie as much as an inherently economic one. Wesley Mouch, in announcing his czar-like plans for the country’s economy, sounds almost exactly like Obama. I’m afraid that too many reviewers will assume that the dialog was written with current Democrats in mind, without realizing that it’s Obama who sounds like Mouch.

That openning scene with Dagny would also have let us see her listening to Richard Halley’s music on her iPod or iPad3. The train, finally on track, speeding off into the dark towards New York, to what Rand described as his “heroic” music, would not only have given us insight into Dagny’s character, it would have given the lie to the idea that only the industrial is beautiful to industrialists.

The overall per-screen take for the weekend was pretty good, (via the Charlottesville Libertarian) and hopefully, good enough to get it some additional screens this weekend when the acid test of a word-of-mouth movie comes. (The movie’s website had actively promoted “demanding” the film, which had resulted in a more screens being added at the last minute, including one in Omaha and one in Lincoln.)

Harmon Kaslow, the movie’s producer, has said that he needs $100 million in box office to justify making Part II. I hope he gets it.

Rand and Cloward-Piven

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC on April 17th, 2011

Leaving the movie aside, since I haven’t seen it yet, this certainly ranks as one of the weirdest criticisms of Atlas Shrugged:

For the past two years Glenn Beck has successfully demonized what he calls the Cloward-Piven strategy amongst his conservative audience. Using a 1966 article written by academics Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, Beck has claimed that progressives are attempting to “collapse the system” by causing an economic downfall. Theoretically, this collapse would then usher in a new, socialist government. However, conservatives seem to be ignoring the fact that the same strategy is used, with an opposite goal, in the newly released movie Atlas Shrugged.

…

Atlas Shrugged is based entirely on “collapsing the system” upon itself in order to achieve a better ends. In the movie, if it stays true to the novel, a group of industrial leaders purposefully leave their businesses in order to collapse the economy.

While Atlas Shrugged reads at times more like a political tome than a novel, that’s no excuse for not reading like a novel.

First, the Strike – the Captains of Industry going on strike to protest their inability to actually create wealth – is a thought experiment. Capitalists, innovators, will do what they love to do, and they’ll find someplace to do it. They won’t go “on strike,” they’ll go to someplace where they can be capitalists. That used to be the US, and in order to demonstrate the thought experiment, Rand had pretty much every other country on earth turned into a People’s Republic, so there was no other place to go.

Second, the capitalists are people, but they’re also a stand-in for capital, which has gone “on strike” in the past, when punished for success, or when regulatory uncertainty is too great. Done so in the past, and may have been doing so for the last couple of years.

Third, at least one half of Cloward-Piven actively encourages street violence to get their way. There’s none of that in Atlas Shrugged. Societal breakdown is never pretty, but from Rand, it’s a warning, from Piven it’s a means.

Finally, and a little tangentially, the goal of the strikers isn’t a more “pro-business” environment. It’s a pro-market regulatory environment. One of Rand’s main points is that Big Business is perfectly able and willing to collude with Big Government and Big Labor to lock out the little guy, whether he be businessman or worker.

Honestly, this looks like another in a series of “I’m Rubber, You’re Glue” arguments by the left.

Motive Force or The Information Superhighway?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PPC on February 15th, 2011

Tax Day has never been this anticipated. Go file your return, and then catch a matinee of Atlas Shrugged. Tom’s already posted the trailer.

Most of the concerns in his post center around fidelity to the book. The compromise between strict fidelity and actual movie-making is always an issue when dealing with a beloved book with rabid fans. It led the first two Harry Potter movies to be little more than scene-by-scene recreations of the books, and pretty much drained the life out of Prince Caspian.

Now, despite Rand’a paean to motive force, Atlas Shrugged isn’t really about railroads. It was written in 1957, and the gradual decline of American railways, along with the special place they hold in our imagination, made them the natural industry for the book to focus on. But today, most Americans don’t ride on long-haul trains, and unless you live near a hub, you look for them on long-distance road trips the same way you’d try to spot buffalo or pronghorn or elk. They’re just not central to most people’s lives the way they were 54 years ago. As someone who helped his dad build N-scale models and is currently working a stone’s throw from The Union Pacific, I take no pleasure in saying this. But it’s true.

No, the book is about stifling innovation and creativity and wealth creation by mediocrity’s need to crush greatness, and the damage that does to all those people who aren’t great. (It’s also about lots of other stuff, too, but that’s the point I want to focus on.) So in an era when people are liable to ask, “why on earth would they stoop to bother about a train?” would the film’s power be better served by making Dagny and Hank something else, something that really is on the cutting edge right now?

You can think of dozens of examples without trying very hard. She’s got an internet business model that will change the world, but it needs Hank’s new infrastructure to carry the data. She’s got a vaccine to cure a disease, but it needs Hank’s delivery system. More bleeding edge: she’s ready to make commercial space travel as common as, well, a commuter rail trip from Boston to NY, but needs Hank’s metal. Wyatt sits ready to provide her the power, but his next-generation nuclear plant sits idle for lack of plutonium.

Obviously, such a substitution would do violence to the project of literally translating the book to the screen, but it’s completely in the spirit of this. The question is, would it get in the way of the story to make the industries affected more immediate, or would it help? Would it complicate or simplify the filmmakers’ task? We have, today, in the headlines, the FCC trying to force internet service providers into being candidate for the DJ Utilities Index. We have, today, Obamacare doing to the same to insurance companies and, eventually, hospitals and doctors. Would a change have made the story more relevant, or just have made the filmmakers seem opportunistic and editorializing?

So while it’s completely unthinkable that Dagny Taggart could be anything other than a railway executive, and that Hank Rearden could have anything other than a super-strong, super-light metal to sell, what if?

With the premiere two months away, it’s probably exactly the wrong time to be asking this question. It’s too late to do anything about it, it would probably just be better to wait and see how well they’ve done with the original source material.

But hey, that’s what blogs are about.

UPDATE: And this, too. A little behind-the-scenes featurette from a few months ago over at reason.tv