Archive for November, 2011

Hear That Whistle Blowin’?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Economics, PPC, President 2012 on November 30th, 2011

It’s not very loud just yet. But if you bend down, ear to the rails, you can hear the ever-so-quiet singing of a train in the distance.

It’s the Hillary Special, and it’s scheduled to pull into 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., on January 21st, 2013.

The engine has always been there, in the railyard, getting refitted and cleaned and tuned up. Bill took it out for its paces a few weeks ago with the comments about Obama’s handling of the economy. Then, of course, came his book, with its false choice between drowning government and crony capitalism.

And now come the test runs, starting with the Wall Street Journal op-ed and the write-in campaign.

The train’s route was made clear by Pat Caddell, in last Friday’s appearance on the Ricochet Podcast. Caddell, along with liberal-but-not-insane pundit partner Douglas Schoen, explained in last week’s Wall Street Journal why Obama had to step aside for Hillary, for the good of the country, and the good of the Democratic Party, not necessarily in that order.

While some read this as desperation and wishful thinking, I’m more inclined to see it as the launching of Hillary’s 2012 exploratory committee. It tests the waters while not committing her to anything, indeed, while not tying her to any possible disloyalty at all.

Caddell’s & Schoen’s idea, in a nutshell, is that Obama can’t win re-election in such a way as to allow him to govern. That in order to win, he’ll have to poison the political environment so thoroughly that cooperation with the Republicans will be impossible, and that the country simply can’t afford that right now. If he loses, he’ll lose whatever gains he’s made for the Left with him. So for Caddell & Schoen, an Obama candidacy is a lose-lose situation.

Worse, Obama is simply giving up on large swatches of the Democrat coalition, in particular working class whites. He’s offered nothing substantial to labor, only the procedural, and is willing at every turn to sacrifice jobs and the economy to the elite green ideologues. (This is a Democrat talking, by the way, not me.)

Hillary, on the other hand, has shrewdly used her tenure at the State Department to build up her own stature as the actual adult in the party, as opposed to the aspirational adult – also known as an adolescent – currently occupying the White House. She’s been disciplined in sticking to foreign policy, keeping her mouth shut about everything else. Even Bill has, according to Caddell, mostly kept his mouth shut.

If in 2000, the country was suffering from Clinton fatigue, it’s now going through some nostalgia for the 90s. Unlike the Bush years, we were (mostly) at peace. Unlike the Obama years, we were prosperous, with a president who seemed to understand the importance of that fact.

Less odious to the center than Obama, Hillary could win with a positive campaign, or at least one without the overt slash-and-burn strategy that Obama is committed to. Once in office, she may be able to cut a grand spending-and-taxing bargain with the Republicans, where Obama has no hope of doing so. Merely by winning, she’ll be able to preserve the key elements of Obamacare, seen by the Left as this generation’s Progressive Great Wave.

Caddell & Schoen remember how, in 1968, when Johnson won only 58% of the vote in New Hampshire, he decided that he didn’t have the stomach for a long primary campaign, even though he stood an excellent shot at re-election against Nixon. He stepped aside in favor of Hubert Humphrey, who might well have won had Johnson stopped bombing Vietnam a couple of weeks sooner. The appeal to Obama’s sense of duty to persuade him to make the same choice.

More than that, they’ll appeal to the same sense of not wanting to fight for renomination. Caddell & Schoen are now trying to get one or several large Democrat donors to run a Hillary Write-In Campaign in New Hampshire. They believe that were she to win a significant percentage of the vote, it might really shake up the race on the Democrat side.

Since it wouldn’t be controlled by or connected to Hillary (wink, wink), Obama couldn’t really tell her to shut it down. Were he to be too forceful, it could allow her to resign and actually run against him, which is the last thing he wants.

I have to admit, I was a little disappointed at the lack of close questioning by the Ricochet gang. A number of Caddell’s assertions were dubious at best, and yet went relatively unchallenged. Obama has abandoned labor on the high-profile projects like Keystone XL. But he’s practically turned the NLRB into an arm of the AFL-CIO. The NLRB itself, as an end-run around the loss of a quorum to conduct business, threatens to invest its general counsel with an unheard amount of unreviewable authority and power.

Bill, as we’ve seen, has not been very quiet of late, complaining about Obama’s handling of the economy. Caddell also claims that Hillary is the only thing keeping Obama’s National Security Advisor in check with respect to Israel, but in fact, we don’t really know what Hillary’s person opinions about Israel are, and there’s plenty of reason to think they’re not particularly friendly. I believe Caddell makes that claim because it appeals to a clearly disaffected part of the Democrat base that remembers, as do most Israelis, Bill as a friend of that state.

Similarly, Caddell appeals to what the Democrat Party once was, but no longer is, when he tosses out with obvious disgust, but does not elaborate on, the notion that Obama will seek to circumvent a hostile Congress by ruling by executive fiat. True enough, but worthy of fuller examination, playing as it does to our fears of a truly imperial Presidency.

Thus, the outlines of the prospective Clinton 2012 campaign. The reality is, of course, is that Hillary would not govern as a centrist. She would likely be a more effective salesman for the old, unimaginative Blue Social Model policies that doom us to Europe’s fiscal fate, however.

That clickety clack that promises to take us back will, instead, leave us all – Obama included – singing the blues in the night.

Nebraska Sand Hills, Thanksgiving 2011

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Photoblogging on November 28th, 2011

Driving back from Denver this time, I took a detour through an area of Nebraska known as the Sand Hills. It’s a part of the state that most people never see, because I-80 is designed to avoid anything interesting. It serves as a very quiet, and largely unheard, rebuke to those who think that Nebraska is table-top flat. (As always, click on the photos for the full size.)

It’s not necessarily the most dramatic scenery. Nothing as majestic as the Rockies. But the hills are essentially large dunes, with enough water around to sustain grass, and therefore ranching, if not farming.

The Ogallala Reservoir is very close to the surface. Close enough that wind power can actually do something useful, like draw water for cattle.

As I said, it’s not exactly the Rockies. But the Hills can be quite high, and you can easily see where the Plains provide ample cover for ambushes and pre-drone, pre-GPS maneuvers. Without a GPS or roads, getting lost out here wouldn’t be difficult. Not getting lost would be.

The non-reflective parts of the lake are frozen. Yep, happens early and ends late out on the Great Plains.

Thucydides The Revisionist

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Iran, War on Islamism on November 21st, 2011

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History

Prof. Donald Kagan

Since it was written, the prism through which we study the Peloponnesian War has been Thucydides’s History. Virtually everything we know about the war, we know through his writing. It was Thucydides who established the first recognizable historical standards, eschewing myth and legend in a way that even Herodotus did not.

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History is Donald Kagan’s attempt to apply – finally – the same critical approach to the History as we do to virtually every other historical record. What makes it special is that it’s not merely Kagan’s attempt, it’s pretty much the only recent attempt to do so.

There must have been different opinions. A war as long-lasting, as all-consuming, as destructive as the Peloponnesian War, must have produced different contemporaneous interpretations. And yet, as Kagan points out, so effectively has Thucydides established his point of view as authoritative, that people aren’t even aware that there were other points of view. In fact, even the facts that Kagan uses to challenge Thucydides’s conclusions come from the History itself.

Kagan would know. He’s been a serious historian of the ancient Greeks at Yale for decades now. (Yale just made his course lectures available in both video and audio online for the first time. His discussion of Greek hoplite warfare alone is worth the price of admission.) His one-volume study of the Peloponnesian War was even a popular hit. “The damn thing sold 10,000 copies,” he says, in evident amazement.

So when Kagan decides that we must treat the History not as a dispassionate academic work, but an apologia pro vita sur, we should take him seriously.

This conclusion leads Kagan to take issue with a number of Thycydides’s conclusions. Thucydides argues that the war was inevitable, the result of an insecure Sparta facing a rising and dynamic Athens, at odds with each other over the proper form of government for Greeks.

It’s true, Kagan says, that there was tension on this point. The Spartans had invited other Greeks to help them put down a Helot rebellion, and then asked the Athenians – and only the Athenians – to leave, worried about where their sympathies might really lie. Later, the Athenians do turn a captured city over to some Helots, frustrating Spartan plans to round them up and return them to servitude, and no doubt increasing their suspicion and mistrust at the same time.

And yet. It wasn’t the two principals who dragged their alliances into war, but two allies who dragged the principals along. Years earlier, with much better odds and with two armies actually facing each other in the field, Sparta had demurred. Pericles knew the Spartan king to be a personal friend and an advocate of peace between the two alliances. When the Spartans took almost a year to actually start the war, they had reduced their demands to something almost symbolic, something so minor that Pericles himself had to persuade the Athenians not to give in. Those living through those years wouldn’t have seen an inevitable conflict between superpowers, but a series of events and miscalculations leading to war.

Thucydides argues that the Sicilian disaster was the result of the unchecked passions of Athenian democracy, in the absence of Periclean wisdom to restrain it. Kagan shows instead that the general entrusted with the mission, Nicias, never really believed in it, made a series of mistakes of omission and commission, and bears primary responsibility for its failure. Thucydides, having argued elsewhere that Athens under Pericles wasn’t really a democracy, is here trying to show what happened when it became one. It’s a game partisan effort, but its central thesis is at least open to question.

Perhaps the most critical question for our times, however, has been what to make of Pericles’s war strategy, and his diplomatic strategy leading up to the war. Pre-war signals that, to Pericles, must have seemed like subtle signals to the Spartans were evidently too subtle. And his war strategy, instead of persuading the Spartans of the uselessness of fighting, merely encouraged them in thinking that they could go on fighting it out along these lines if it took all summer. Or indefinitely.

In the entanglement that would eventually lead to the war, Pericles adopted a defensive treaty with Corcyra, primarily directed against Corinth. Then, when the crunch came, he sent, from the ancient world’s largest navy, a force so small that it had to be doubled by the Athenian assembly, with instructions only to intervene if it looked as though their ally might lose. While they eventually did intervene to save Corcyra, their manner of doing so neither assuaged the Corinthians, nor earned them the loyalty of their ally.

Nor did Pericles understand the internal politics of Sparta as well as he thought. Knowing that at least one of the kings was opposed to war, he attributed to him far more political influence than he actually was able to exert in the Spartan assembly. As a result, when Corinth accused Athens of breaking the 30-Years’ Truce – in fact, Athens had stayed just within the lines – Pericles had already undercut the position of a relatively weak office.

Kagan argues that Thucydides, as a member of the Periclean political party, is seeking to recast a series of bad decisions by Pericles as part of an irresistible chain of events. Instead, his policy should be seen as one of weakness masquerading as diplomacy and moderation, combined with a deeply mistaken sense of when and where to take a stand.When Sparta did finally declare war, it eventually narrowed its demands down to a rescission of the Megaran Decree, a punitive prohibition of access to the Athenian marketplace to residents of Megara. What led Pericles to argue against a tactful withdrawal from the Megaran Decree was his belief that he had a winning strategy for the war, one that would lower its cost in terms of both lives and treasure to the point where it would be worth it to make the point, and prevent potential unrest throughout the empire. Contrary to all previous Greek strategy, Athens would barely fight. It would play rope-a-dope, letting Sparta punch itself out with destructive, but ultimately futile raids, and make it pay a price by attacking its coastal cities, as only a naval power could do. Eventually, the Spartans would decide that they couldn’t force Athens to surrender this way, and come to terms.

As we know, things didn’t quite work out that way. And yet, even as he – along with a large portion of the Athenian population – was dying from a overcrowding-enhanced plague, Pericles (reports Thucydides) said that he was happy that his strategy had ensured that no Athenians had died by force. Historians have long noted echoes of his Funeral Oration in the Gettysburg Address, but up until this point, in his handling of the crisis, Pericles reminds us more of another president.

Thucydides argues that had the Athenians but kept to Pericles’s strategy, they would have won the war. This seems to stem more from his distaste for the low political tone set by Cleon, the successful commander and politician than from the evidence. In fact, the Athenians, once they pursued an active ground war, quickly won victories and brought the Spartans to sue for peace. Merely raiding coastal cities wasn’t enough; the Spartans had to be afraid that the Athenians would pursue and offensive strategy, invade, and potentially free the helots (or at least severely disrupt the Spartan social order), to sue for peace. They had to fear being beaten, humiliated, and impoverished, not merely wasting their time.

It’s a point that those who would argue for a strategy based solely on missiles and naval power would do well to learn, and it bodes ill for a style of warfare dedicated to dismantling an opponent’s military while leaving the population at large untouched.

Likewise, societies can only absorb so many hits, even superficial ones, without reprisal, before morale begins to erode. The Germans had to re-learn this lesson in WWI, as they sought a quick victory over France, while letting the Russians advance virtually unopposed over East Prussia, ancestral home to the Junker military professionals who had concocted the war in the first place. Whether or not the troops removed from the French front to the east were dispositive is open to question; it’s certain that the second front was a distraction.

Why do we care about the Greeks? Why, even now, 2500 years later, do we still read about their wars, against each and against their neighbor, the imperial eastern superpower?

The Greeks are a lot like us, and by learning about them, we hope to learn about ourselves. Not for nothing are the twin pillars of Western civilization Jerusalem and Athens. We see in ourselves echoes of our fractious, democratic, pluralistic, pious, postmodern Greeks. If we can see what stresses a long epoch of war places on a society, we can at least avoid being surprised.

If we’ve been learning those lessons from the wrong reading of Thucydides, then we’ve quite possibly been learning the wrong lessons. If we believe that wars are inevitable, we will fail to take our decision-making seriously. If we learn that “democracy” cannot make large strategic decisions, we abandon our core value of open debate, and are likely to fail to hold our generals properly accountable.

And if we learn that we can avoid wars by looking non-threatening, and win them merely by showing that we can, we’ll lose.

The Naked City

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on November 17th, 2011

That was tonight’s Netflix special. Sort of a 1948 version of Law & Order, on location in New York, following the police solve a crime, pre-high tech forensics. And of course, Sam Waterston doesn’t have to put up with a world-wise voice-over giving advice to detectives and criminals alike. The narration flattens out what could be a pretty compelling story.

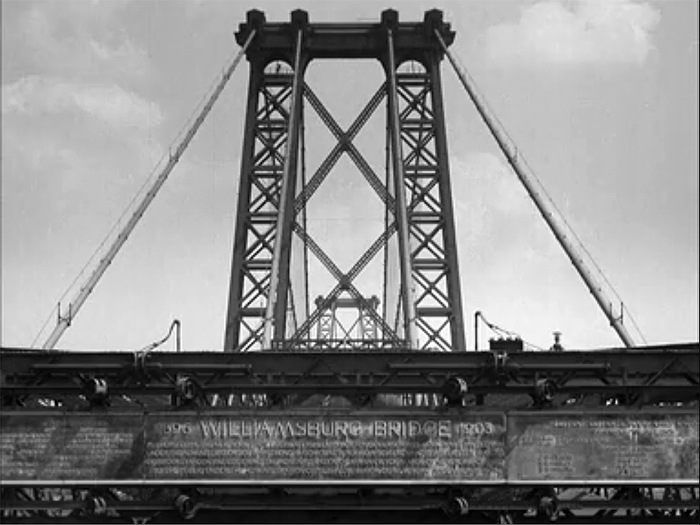

Towards the end, though, at the climactic chase scene, we get some terrific views of and from the Williamsburg Bridge:

Not only is the bridge still there, but like many of Manhattan’s bridges, you can still walk across it. Notice the subway train coming in the opposite direction down the middle?

And a picture I happened to take a couple of years ago:

They replaced the lower fence, and added a taller grill to the outside as well, probably to discourage people from jumping, or climbing the gridwork. They also paved the walkway, and added instructions for bikers and pedestrians about which way to face.

This shot was perhaps the most interesting:

You could spend a day figuring this out. Fortunately, I had some help. The bridge currently carrier cars, the subway, and foot traffic, but it used to have trolleys and streetcars as well. The streetcars would be permanently gone by the end of 1948, but continued to operate on the south side of the bridge until then. This picture was taken on the north side of the bridge, which had evidently already been given over to automobile traffic. Look at which way the cars under the bridge are headed. This only makes sense if the plea for politeness posted from the walkway is for cars travelling away from you, and the north side handles two-way car traffic.

At the same time, while the subway wouldn’t stop in the middle of the bridge, those towers actually go all the way down to the ground (we’re near the Manhattan end of the bridge here), and were meant to provide access to the streetcars. If you wanted to change directions, you needed to cross over the bridge, and on foot, this was the only place you could do that until the other end of the bridge, over in Brooklyn. Thus the catwalk across the bridge, which has since been removed:

Aside from the Google labeling that turns the picture into a scene from the new BBC Sherlock Holmes production, I can’t help but think this is a depressing come-down for the bridge. They kept the circular stairway, but you can’t get there from there, so the walkways and towers would be purely decorative, if they weren’t so ugly.

We can’t end on that picture. We just can’t.

Sun Sets On Solar

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Energy, PPC on November 15th, 2011

Chinese solar manufacturers, heavily subsidized by the Chinese government though they are, are not completely immune from the laws of economics. Faced with falling demand, falling prices, and growing inventories, they’re cutting production. The follows on the heels of a number of high-profile failures of solar manufacturers here in the states.

True that the Chinese government, in its relentless mercantilism, was, and is, subsidizing solar heavily enough that three of their companies may survive the shakeout, whereas it’s possible none of ours will. But in fact, they were just responding to a market that largely existed because of European and American solar subsidies in the first place. The collapse of solar prices isn’t about new manufacturing techniques (yet), it’s about Europeans realizing that not only is the energy more than they can afford, so are the jobs, and they’re mostly going overseas, anyway.

The irony is that we’re still being told that we need to “invest” in solar because the Chinese are committed to it, and that must validate the idea. It turns out that the Chinese were only invested in it because they figured to have us as their high-priced customers. Not only were we funding both sides in the solar arms race, we were using the result to justify nonsense subsidies like Solyndra and LightSquared. It’s like one of those experiments where the monkey reacts to itself in the mirror. Only in this case, it was more like Lucy and Harpo pretending to fool each other.

Colorado, under former Governer Bill Ritter, began to pursue a “New Energy Economy,” chasing and subsidizing alternative energy companies, hoping to lure them to the state. Ritter was elected in 2006, and the financial meltdown and succeeding recession created revenue shortfalls that limited the damage he could do. The latest brouhaha over missing funds at the Governor’s Energy Office hasn’t done their cause any good, either.

The ideologues won’t be swayed, of course, but perhaps many of the more pragmatic politicians can be persuaded that these are bad bets for governments to be making.

President Golf Calls You Lazy – Again

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Regulation on November 14th, 2011

In what was called a “scripted conversation” with Boeing’s CEO James McNerney, Jr., President Obama reprised his Malaise Moment of a few weeks ago, and said, “We’ve been a little bit lazy, I think, over the last couple of decades,” which resulted in the 2009 dropoff in Foreign Direct Investment in the United States.

I have to admit that my first reaction was that I was too busy to be bothered with replying. But, as the saying goes, sharks gotta swim and bats gotta fly.

Taken at face value, I don’t have any idea what the hell he was talking about. Worse, I don’t think he does, either. Certainly even a cursory examination of the facts would reinforce the conclusion that Obama’s grasp of recent economic history isn’t any better than his grasp of mid-century diplomatic history.

Below is a quarterly graph of foreign direct investment in the United States, starting in 1980. The series starts in 1960, but it roughly zero from then until 1980, owing to the fact that the US, generating the lion’s share of the world’s wealth, was relying on exports more than FDI for growth:

You can see a couple of patterns here. First, FDI accelerates through the business cycle, as expected. As the economy picks up steam, it generates interest abroad and confidence in investors looking for growth. Second, over the last “couple of decades,” FDI has grown through each business cycle, if you discount the dot-com bubble evident in the very late 90s. Third, when the US economy goes into recession, foreigners stop investing here, until they see some evidence of a bounce-back. All of these patterns clearly apply to the most recent recession, and the current economy.

Of course, we all knew this was bunk, anyway. National accounts must balance, and the only way we can finance our trade deficit is through FDI in our economy. If we find ourselves unable to generate enough wealth, or attract enough investment, to import the things we want, that’s indeed an indictment of our ability to compete, but it likely has much more to do with government policy and regulation than with the work ethic of most Americans.

Obama’s statement that this pattern existed over “the last couple of decades,” is, I think, an attempt to include Bill Clinton’s presidency in his criticism, a back-handed return volley to Clinton’s oblique criticisms of Obama’s economic policies. It’s more than just his routine scolding of his fellow citizens, it also contains a domestic partisan political component, as well. One wants to resist the temptation to overstate the electoral consequences of such tension. But it may be that the President’s famously thin skin is once again getting the better of his judgment.

At this rate, maybe his staff should just use that XtraNorml animation engine for any future “scripted conversations.”

Notes on the State of Virginia

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PPC on November 9th, 2011

Coming as I do from Virginia, I like to keep an eye on the politics of the old country. Virginia is one of the few states to hold its elections in odd-numbered years. As a result, their elections are often seen as better bellwethers than the Congressional mid-terms. (This is a little odd, inasmuch as, in the last 11 gubernatorial elections, Virginians have voted against the party in the White House. Virginia governors can’t succeed themselves, but they can run again after sitting it out, and Mills Godwin holds the distinction of being both the last Democrat elected under a Democratic President, and the last Republican elected governor under a Republican President.)

This year, the Republicans entered the post-2010 Census elections with 58 seats in the House of Burgess- er, Delegate, and 18 seats in the State Senate. Holding the governorship meant that they needed only one seat to regain control of the State Senate.

The results show the perils and power of redistricting. Unlike in Colorado, state legislative redistricting is done by the legislature itself. With a split legislature, the Senate and House agreed to draw their own maps for their own chamber, and to abide by the other house’s map. So the Senate Democrats and House Republicans, essentially, got to draw the maps for the Senate and House, respectively.

The Republicans ended up taking an astonishing 67 seats in the House, but they could only manage a 20-20 tie in the Senate. That’s good enough for control, but the Republican Lt. Governor will be spending a lot of time up at the state capitol building over the next two years.

These results mask the utter collapse of the Democrat party in the Old Dominion. Though they’ll never say so, the Democrats made a strategic decision to sacrifice the House to try to hold onto the Senate. Of seven Senate races decided by less than 10%, the Democrats won five, and came within half a percentage point of a sixth. In the House, they lost all six.

Statewide, the Democrats received an aggregate 34% of the vote in the House, and just under 40% of the vote in the Senate. The Republicans out-polled the Democrats roughly 3-2, and still ended up with only a tie. Democrats didn’t even bother to run in 12 of the 40 Senate districts. (Republicans vacated the field in only four.) In the House, it’s even worse. Republicans didn’t compete in 27 districts, but Democrats only ran in 54 districts. Put another way, the Republicans could have lost in almost every contested race, and still won control of the House.

This may be a mixed blessing for the Republicans. As Colorado House Republicans have found out over the last year, governing with a majority of one vote is often worse than being in the minority; in effect, you don’t have working control of the body. You can kill and pass lots of stuff in committee, but when it gets to the floor, the minority can almost always count on standing together in opposition, while they need only pick off the squishiest member of your caucus on any given vote. The net result for Virginia may be that the Republicans are perceived as having full governing authority, while not necessarily having full governing power.

For 2012, though, it’s probably very good news for Republicans. I can’t imagine President Obama carrying the state, and even a popular ex-governor like Tim Kaine will be facing a daunting structural deficit (something Democrats are excellent at creating).

Wahoowah.

Field Work at DU

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PPC on November 8th, 2011

I didn’t do the field work. I was the field work.

For the last several years, I’ve been lucky enough to be invited to be the Conservative for Inspection by the Students at Prof. Christina Foust’s class on Anarcism and Conservatism. It’s always a terrific experience, being able to put conservative ideas in front of a set of students who probably don’t hear them very often on campus. And Prof. Foust, despite admitting to being left-of-center, has been unfailingly gracious, has always let the discussion go where it may.

This year was no different, although instead of me responding to questions and expounding on conservative solutions to the world’s problems, we tried to get the students more involved, asking them to explain their questions, come up with their own answers, and show how rhetoric is used to frame an issue by one side or another. Many of the students who take the course are prospective business students for some reason, so they tend to be focused on economic & business questions, and we did indeed spend a fair amount of time on those. But when we took up the question of taxing & spending, I took the opportunity to reframe it as one of government power, in a way that readers of this blog will be familiar with. It was, I hope, a small revelation for them. As was the emphasis on federalism and the role of the states as laboratories of democracy.

One student asked an interesting question about what they, as individuals, could do to help out with regards to the economy. I decided to take an economic rather than a political attitude towards the question. Alluding to Arnold Kling’s analogy of the Great Recalculation, as opposed to the Hydraulic Model of the economy, I suggested that 1) they should make themselves as appealing to potential employers as possible, and 2) they should think about starting businesses of their own. Both are necessary, as our economy adapts, and we struggle to figure out what goods and services people are willing to pay for.

At the end of the class, we took up the question of higher education, and how their time at the school would affect their lives. With most of them being business majors, I thought it was a good opportunity to mention the value that the much-derided humanities could have in their lives later on. Although I was a physics and math major, I took a number of history courses in school. I was graduating in 1987, and I had every reason to believe that my career would be spent fighting the Soviet Union. My ability to do that, to maintain perspective on that great struggle, and to stay grounded in it, would be enhanced by a greater understanding of world and European history. Even after I changed careers, I found that my most rewarding moments in b-school and as an equities research analyst were when I saw how understanding business, and understanding human nature and how the world works, are really one in the same.

The key element, I think, is that they need to take the classic authors on their own terms, not the politically-charged and ethnic- and gender- and all-too-abstract ways that many professors would try to present them. Immediately after the class, I happened to pick up a copy of the September 2001 Journal of Political Science, just to see what people were writing about before the world changed. There was an article about “Thucydides as Constructivist.” It’s a shame I didn’t look at it immediately before the class, because it’s exactly the kind of thing I would have advised the students to avoid, as utterly irrelevant to the historical lessons they should be getting from the History. Thucydides is writing a history of a war that actually happened, between two states and two ways of governing, and it’s important not to lose sight of the story he’s telling. The biases we should care about stem from his own political and military involvement in that war, not from some backward-projected modern critical categories.

Last week, the guests had been anarchists, so I took advantage of the home field advantage to compare (unfavorably) the OWS protestors with the Tea Party, in particular to show how the rhetoric being used by the Occupation is deliberately aimed so as to confuse the differences between the two. Hey, these kids are going to be making decisions someday; best that they know right from wrong.