Archive for September, 2018

The Deep State, “Credible” Allegations: The Devil and Daniel Webster

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 23rd, 2018

The Devil, in this case, being politics as we know it today, practiced yesterday.

In 1842, Daniel Webster was John Tyler’s Secretary of State. Among the issues he had to deal with was a lingering dispute – since the Revolutionary War – between the US and Britain over the border between Maine and Canada. One obstacle to a settlement was the maximalist demands of Maine itself, whose senators would be voting on the treaty, and whose people would have to be relied on not to make trouble by trying to settle territory ceded to Britain and precipitating a war.

Parallel to the negotiations, Webster helped arrange for federal funds to secretly underwrite a public relations campaign in Maine in support of the proposed settlement. The treaty was eventually approved by the Senate by a vote of 39-9.

However, later, in 1846, Charles Jared Ingersoll, a Democratic congressman from Philadelphia, went on a tirade in the House against the treaty. He was particularly incensed that Webster had settled the Maine boundary without also settling the Oregon boundary. He also revived some old charges from years before. Webster, back in the Senate and rising to the bait, fired back ferociously. “He was not known for his invective, but here, it was reported, the invective exceeded that of Cicero, Burke, and Sheridan, to say nothing of Randolph, Clay, and Benton.”

Ingersoll figured he had hit a nerve.

“Where there was so much wrath, there must be guilt, so he now pursued his investigation into the State Department. There he discovered the expenditures from the secret service fund [this is not the Secret Service we know today, founded in 1865 -ed.]. Returning to the House, he charged Webster with misappropriation of funds and corruption of the press, and demanded an investigation. The refusal of President James K. Polk to break the seal of secrecy on the contingency fund, combined with Tyler’s testimony defending Webster and assuming full responsibility for the expenditures, doomed the project.”

It doomed Ingersoll, but in fact, Webster had been using clandestine taxpayer funds to run a domestic PR campaign in support of a treaty he negotiated. This may not rise quite to the level of leaking information to the press in order to use press stories to obtain surveillance warrants, but it is kinda of deep-statish.

Back in 1842, Webster was fighting off another kind of allegation all too familiar.

“In January 1842, George Prentice had published in the Louisville Daily Journal an editorial, ‘Anecdote of Daniel Webster,’ that gave a lurid account of [Webster’s] seduction of the wife of a poor clerk in his department. She had come to him asking employment as a secretary. After sending her to an adjoining room to provide a specimen of her handwriting, Webster came in, closed the door, and pounced on her… She screamed and clerks rushed in, thus forestalling ‘the old debauchee.’ Affidavits from Washington, one of them filed by Webster himself with a local magistrate, forced Prentice to retract the story…”

The story never found any real audience then or now, and he always blamed Clay for having planted it. But the fact that he was forced to deny it seemed to stain him all by itself.

Plus ça change.

Operation Finale

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Movies on September 23rd, 2018

“Our memory reaches back through recorded history. The book of memory still lies open. And you here now are the hand that holds the pen.

“If you succeed, for the first time in our history we will judge our executioner.”

With these words, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion sends the special Mossad unit off on its mission to Buenos Aires, to capture the Architect of the Final Solution and retrieve him to Israel to face justice, or at least as much justice as this world has to offer. It is an arresting, energizing moment in Operation Finale, Oscar Isaac’s film treatment of one of the Mossad’s early high-profile successes, and a defining moment itself in Jewish history.

The quote is especially apt, as much of the criticism of the movie revolves, wittingly or not, around the distinction between history and memory, and blurring that distinction in the name of art and commerce. Some of these compromises are valid. Others are unfortunate because unnecessary; the real operation had plenty of tension in real life.

There are more recent accounts, but Isser Harel’s The House on Garibaldi Street still captures most of the key operational details, as well as its flavor and atmosphere. In it, the then-head of the Mossad recounts the tip that led to the investigation, as well as the operational difficulties of working in a country far from home with a language barrier. Harel, for instance, ran the operation from diners, on a rotation known to the operatives, where they would meet and pass messages. The movie shows this briefly, but misses an amusing and potentially fatal error – the cafes that Harel had a “back room,” but by Argentinian custom, that room was almost exclusively used by women, making him stand out like a sore thumb and forcing a change in technique.

Also amusing was the difficulty that the team had in obtaining reliable transportation. Car after car broke down or had tire problems, or some other mechanical issue. They couldn’t rent or buy an expensive car for fear of attracting attention, so they were stuck with a series of lemons that might fail them at any moment, up to and including the decisive drive to the airport. Instead, we just see a lot of greenbacks changing hands for a couple of local cars.

There were multiple safe houses, with compromises made in choosing each one. There were questions about the safety of the route to the airport, and the possibility of using a shipping container was discussed, but during the operation as a backup, not in the initial planning as shown. And there was considerable concern about the diplomatic fallout with Argentina, all of which was justified by later events.

Isaac chooses to forego all of this real-life drama for what amount to three major historical compromises. First, El Al, which loaned the plane to Mossad, didn’t require a signed statement by Eichmann that he was going of his own free will. Second, there was no last-minute frenzied escape at the airport, hotly pursued by Nazi-infested Argentine police. Third, and related Graciela Sirota was not tortured in an effort to discover their location. To varying degrees, these historical compromises serve memory. They also, to varying degrees, do a disservice to the movie.

The conceit that El Al required Eichmann to sign a statement in order to permit the Mossad to transport him sets up an interrogation thread after Eichmann’s capture and removal to the safe house. Strictly historically, the Israelis who were charged with babysitting Eichmann did suffer psychologically from having to deal with him, and did end up slowly bending the strict minimum-contact rules that were initially imposed. Those were the result of 10 days in close contact, not a need to extract a statement. But the narrative thread serves another purpose, essentially moving Eichmann’s eventual defense from the trial into the safe house. To that extent, it’s perfectly good filmmaking. The memory of what Eichmann claimed remains the same, the story line is just compressed.

The other two compromises – offshoots of one invention, actually – are less defensible. The Israelis expected that Eichmann’s family would be loath to go to the police with a missing persons complaint, precisely because his presence in Argentina was under an assumed name. Giving a plausible reason for his kidnapping would mean blowing his cover. But it also means that while there was a surreptitious low-level search, there were none of the resources available that a full police investigation would have had. No close calls with people staring in windows, no mad dash to the airport after a hair-breadth escape, no police chasing down the airplane as it took off. This is pure cinematic dramatic invention, when drama would have been better-served by honing in on the operational issues.

The last incident – the torture of Graciela Sirota – happened, but the movie places it in the context of the chase. In fact, Miss Sirota was tortured and left with a swastika tattoo in June 1962, after Eichmann’s execution. It was part of a larger antisemitic backlash against the local Jewish community, and both its occurrence and the police indifference to it prompted a broad reaction in Argentinian society, isolating the antisemitic elements, and forcing the government to take action against the groups responsible. This is all chronicled in “The Eichmann Kidnapping: Its Effects on Argentine-Israeli Relations and the Local Jewish Community,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 7, No., 3, Spring-Summer 2001. So in this case, even the memory is somewhat garbled.

If the reader has made it this far, he probably thinks I didn’t much like the film, but I did. The character development is first-rate. The head-butting between Eichmann and Oscar Issac’s Malkin fulfills Israel’s promise to let Eichmann have his say. For those who don’t know better, one form of suspense about the outcome is as good as another. So the movie is good, as a movie. In its important parts, it’s even pretty good as memory. But it could have been better at both those things, and still better as history.

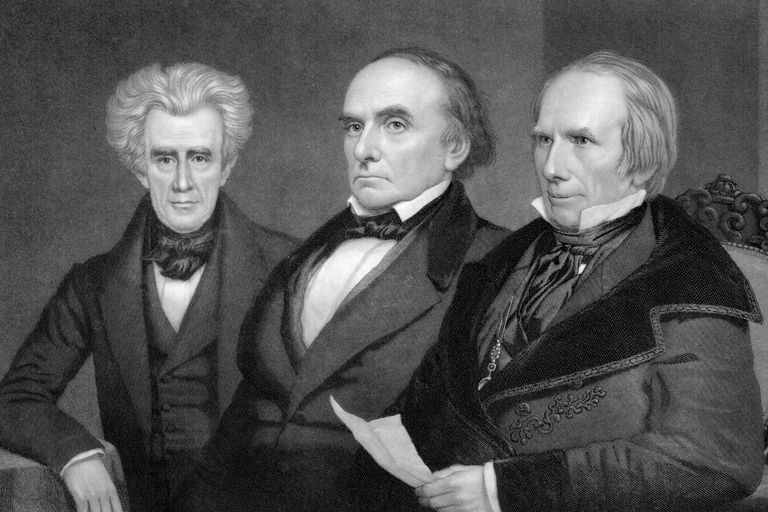

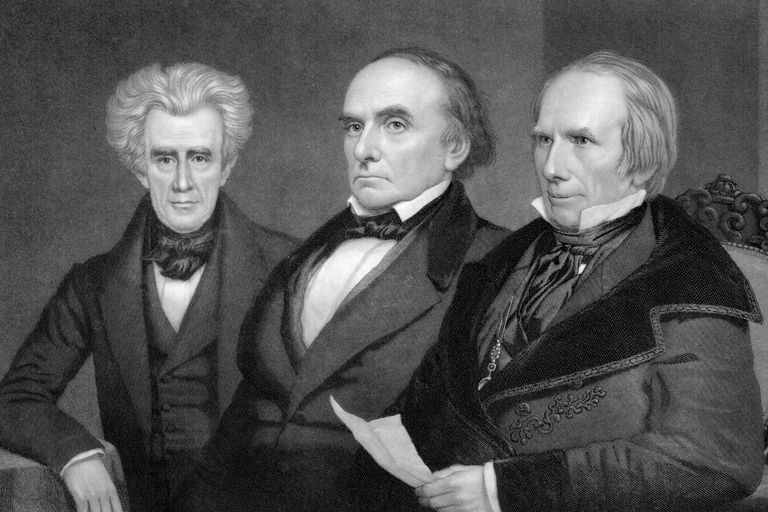

The Great Triumvirate

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 20th, 2018

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

Since it’s 2018, and not 1838, things differ. But pretty much every reading of American history is a lesson in how our own political dynamics have deep roots.

For instance, our political system is, as one wag put it, “ridiculously over-designed” when it comes to distributing political power. We not only have federalism, which limits the national government and reserves most policy-making to the states. We also have, at every level of government, separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. These structures were so over-designed that it has taken a couple of centuries and the trojan-horsing of late 19th Century European political ideas inside our walls to break down these barriers.

Given the proximity to the Founding – the creation of the Constitution was still a living memory into this period, one might therefore think that one party would be dedicated to a concentration of power, and one party dedicated to a distribution of power as the Founders intended. That roughly, although not perfectly, mirrors the situation today.

But in the Clay Whig vs. Jackson Democrat era, it didn’t. The Whigs sought broader federal powers, especially as regards internal improvements and protectionist tariffs, but legislative supremacy at the federal level and vigorous westward expansion. The Democrats wanted to devolve federal power and money back to the states, but concentrate federal power in the executive. In other words, each sought to adhere strictly to certain aspect of the Constitutional distribution of powers, while stretching others to achieve its desired political ends. (It goes without saying that neither had yet conceived of the bureaucratic state as a means of immunizing their policy preferences from popular opinion.)

The Jacksonians saw themselves as the logical extension of the “Spirit of ’98” and the Jeffersonian revolution of 1800, which is why, up until the current history purge, Democrats called their annual county dinners “Jefferson-Jackson Day” dinners.

Webster, never the leader of the Whigs but their most active campaigner in 1840, sought to turn the tables on them, relishing “beating the Democrats at their own game.” He campaigned on the idea that returning power to the legislature was fulfilling the Jeffersonian idea. The Democrats were appalled at his claim, but given the deep economic depression in 1840, nothing they said was likely to make much of an impression on the voting public.