Archive for category History

The Democrats’ Assault on Free Speech Continues

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, National Politics, Political History on November 17th, 2020

Joe Biden has selected Richard Stengel to head up state-owned media for his transition team. This includes overseas media such as Voice of America and our Middle East Broadcasting Networks.

Stengel was an Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs under the Obama Administration. Apparently, his big takeaway from that post was that the First Amendment’s free speech protections, being unique in the world, are deeply and profoundly flawed.

For some of us, American Exceptionalism is a feature. For the likely incoming administration, it is a bug. In the case of Stengel, it’s clear that he doesn’t even understand how the First Amendment protections of speech are supposed to work. He mocks that, “…the Framers believed this marketplace was necessary for people to make informed choices in a democracy. Somehow, magically, truth would emerge.”

There’s nothing magic about it, and there’s no guarantee that “the truth” will always emerge. Indeed, there’s no guarantee that there is a truth to emerge. The Founders believed, instead, that the government was a terrible vehicle for determining what speech was acceptable and what speech wasn’t. Anyone empowered to make those decisions would inevitably put his thumb on the scale, and a government empowered to do so would use that power to silence opposition.

For those of you on the other team, before you cheer too loudly, consider the possibility that you may not always be the ones defining “hate speech.” Along those lines, it is worth considering what will likely not qualify as “hate speech.” The Democrats consistently opposed extending Article VI protections under the Civil Rights Act to Jews, and consistently opposed adopting the IHRA definition of Anti-Semitism. I would oppose a “hate speech” exception to the First Amendment even if the Democrats had not reflexively opposed President Trump’s attempts to extend civil rights protections to Jews, however. Special protections extended can be special protections retracted, and even the threat to do so could be used to extract political concessions. That’s the point.

Many of us voted for Trump out of self-defense, to protect ourselves against the use of the government to attack us or censor us for our political or social opinions. Many of us were quite clear about that before the election. This sort of thing is exactly why.

The Great Triumvirate, Summarized

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 10th, 2018

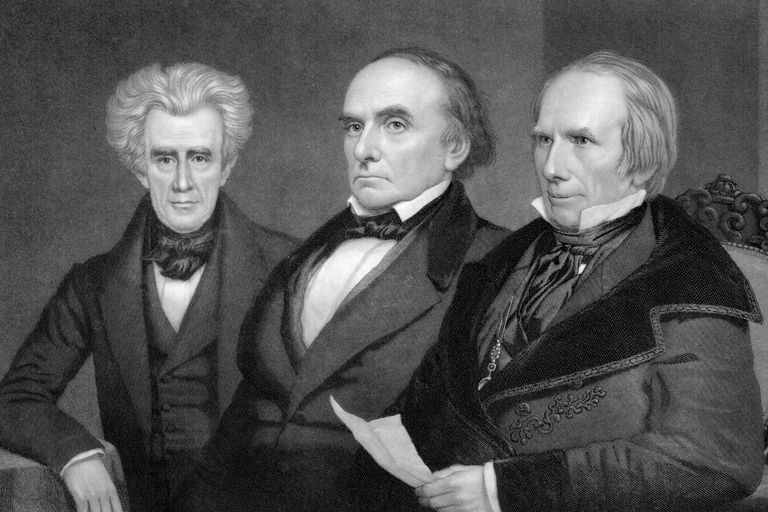

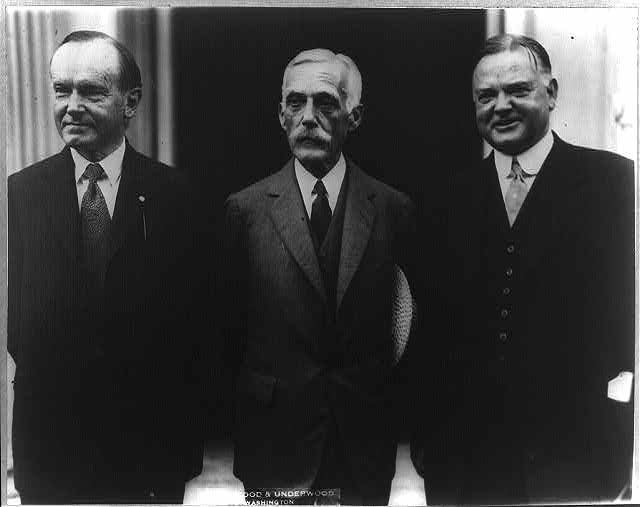

Tonight was our book club meeting for The Great Triumvirate, Merrill Peterson’s seminal history of the second generation of American political leadership – Clay, Webster, and Calhoun.

Tonight was our book club meeting for The Great Triumvirate, Merrill Peterson’s seminal history of the second generation of American political leadership – Clay, Webster, and Calhoun.

In discussing the differences among the three, and summing up, a point occurred to me that I hadn’t thought of until I offered it to the group: each man’s greatest strength represented a singular aspect of statesmanship.

Clay was the consummate legislator, putting together a comprehensive program of action, and adhering to the principle that politics is the art of compromising without being compromised. He was a bit of a peacock, but he also did the hard work of figuring out where there was common ground, allowing people to give without betraying their principles.

Perfect for a legislator, but perhaps not so much for an executive, and country might well be better off that Clay never became president. As secretary of state, he hated the drudgery of paperwork and administrative work. And while he defined the pragmatic vision of the Whigs, he made the party over so much in his image that it didn’t long survive his death.

Webster was the great rhetorician, able to encapsulate an argument or an idea in a monumental speech. To him belong three of the greatest speeches of the 19th Century – the Plymouth Oration, the Bunker Hill Monument, and the Second Reply to Hayne. None of the main ideas is original, but each cemented in the public mind core principles of the republic.

And yet, for all his rhetorical brilliance, Webster was always going to be a follower, never the leader of either the Federalists or the Whigs. Of the three, he might have made the best president. As secretary of state, he made efficient use of his executive power. But because he could never lead his party, he would never even so much as sniff a nomination.

Calhoun was the theoretician, constructing a philosophical system to defend the south, its way of life, and of course, slavery. His great image of the Union as a contract among sovereign states rather than a covenant among free people would prove flexible enough to let him manipulate the Senate for decades, usually in opposition.

But in its service, Calhoun proved bafflingly flexible himself, finding principles convenient to the debate of the moment that he believed could fit in his overall philosophical framework. This let him maintain an iron grip on South Carolina politics, and eventually endeared him to much of the South, but in his lifetime, it left him isolated. Without a party or national vision, it’s hard to see how he could have governed as president.

Of course, these were only strengths, not the sum total of their political skills. Clay could speak. and buried in his American system was a philosophy of government. Webster understood ideas as well as anyone, and could compromise to get bills passed. And Calhoun’s rhetoric was sharp, if unimaginative, and he knew how to frame issues to draw distinctions and gain allies.

Still, the life’s work and achievements of each would be defined by their typical working styles – Clay the pragmatist; Webster the speaker, and Calhoun the thinker.

The Deep State, “Credible” Allegations: The Devil and Daniel Webster

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 23rd, 2018

The Devil, in this case, being politics as we know it today, practiced yesterday.

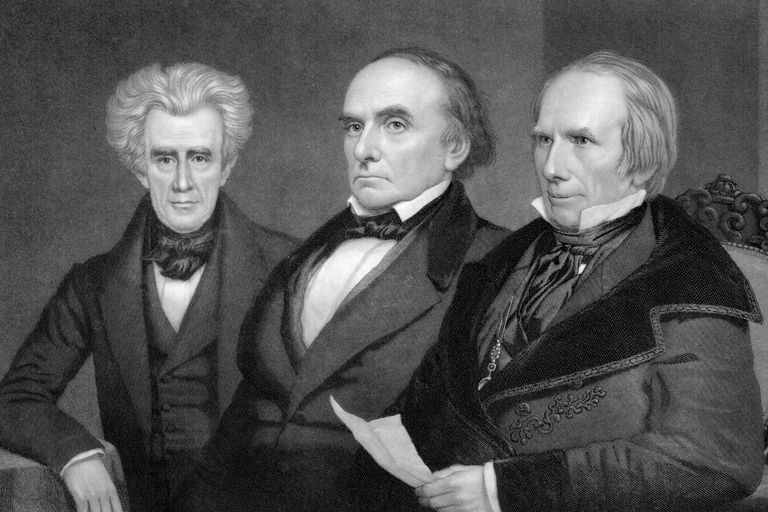

In 1842, Daniel Webster was John Tyler’s Secretary of State. Among the issues he had to deal with was a lingering dispute – since the Revolutionary War – between the US and Britain over the border between Maine and Canada. One obstacle to a settlement was the maximalist demands of Maine itself, whose senators would be voting on the treaty, and whose people would have to be relied on not to make trouble by trying to settle territory ceded to Britain and precipitating a war.

Parallel to the negotiations, Webster helped arrange for federal funds to secretly underwrite a public relations campaign in Maine in support of the proposed settlement. The treaty was eventually approved by the Senate by a vote of 39-9.

However, later, in 1846, Charles Jared Ingersoll, a Democratic congressman from Philadelphia, went on a tirade in the House against the treaty. He was particularly incensed that Webster had settled the Maine boundary without also settling the Oregon boundary. He also revived some old charges from years before. Webster, back in the Senate and rising to the bait, fired back ferociously. “He was not known for his invective, but here, it was reported, the invective exceeded that of Cicero, Burke, and Sheridan, to say nothing of Randolph, Clay, and Benton.”

Ingersoll figured he had hit a nerve.

“Where there was so much wrath, there must be guilt, so he now pursued his investigation into the State Department. There he discovered the expenditures from the secret service fund [this is not the Secret Service we know today, founded in 1865 -ed.]. Returning to the House, he charged Webster with misappropriation of funds and corruption of the press, and demanded an investigation. The refusal of President James K. Polk to break the seal of secrecy on the contingency fund, combined with Tyler’s testimony defending Webster and assuming full responsibility for the expenditures, doomed the project.”

It doomed Ingersoll, but in fact, Webster had been using clandestine taxpayer funds to run a domestic PR campaign in support of a treaty he negotiated. This may not rise quite to the level of leaking information to the press in order to use press stories to obtain surveillance warrants, but it is kinda of deep-statish.

Back in 1842, Webster was fighting off another kind of allegation all too familiar.

“In January 1842, George Prentice had published in the Louisville Daily Journal an editorial, ‘Anecdote of Daniel Webster,’ that gave a lurid account of [Webster’s] seduction of the wife of a poor clerk in his department. She had come to him asking employment as a secretary. After sending her to an adjoining room to provide a specimen of her handwriting, Webster came in, closed the door, and pounced on her… She screamed and clerks rushed in, thus forestalling ‘the old debauchee.’ Affidavits from Washington, one of them filed by Webster himself with a local magistrate, forced Prentice to retract the story…”

The story never found any real audience then or now, and he always blamed Clay for having planted it. But the fact that he was forced to deny it seemed to stain him all by itself.

Plus ça change.

The Great Triumvirate

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 20th, 2018

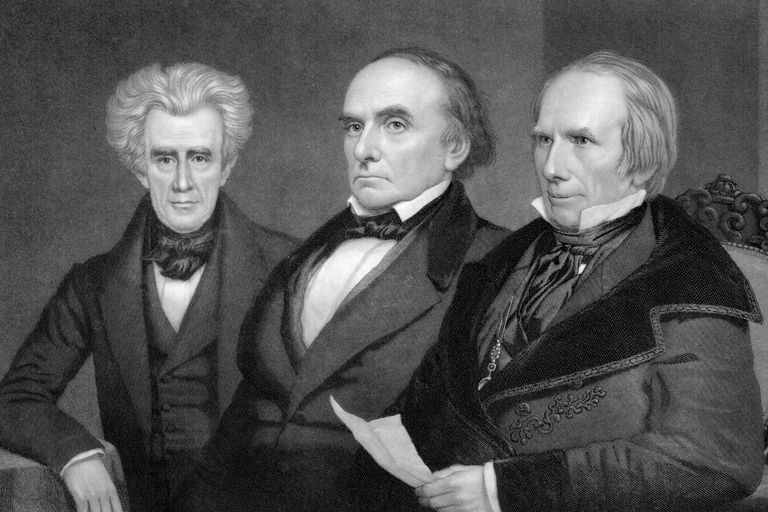

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

Since it’s 2018, and not 1838, things differ. But pretty much every reading of American history is a lesson in how our own political dynamics have deep roots.

For instance, our political system is, as one wag put it, “ridiculously over-designed” when it comes to distributing political power. We not only have federalism, which limits the national government and reserves most policy-making to the states. We also have, at every level of government, separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. These structures were so over-designed that it has taken a couple of centuries and the trojan-horsing of late 19th Century European political ideas inside our walls to break down these barriers.

Given the proximity to the Founding – the creation of the Constitution was still a living memory into this period, one might therefore think that one party would be dedicated to a concentration of power, and one party dedicated to a distribution of power as the Founders intended. That roughly, although not perfectly, mirrors the situation today.

But in the Clay Whig vs. Jackson Democrat era, it didn’t. The Whigs sought broader federal powers, especially as regards internal improvements and protectionist tariffs, but legislative supremacy at the federal level and vigorous westward expansion. The Democrats wanted to devolve federal power and money back to the states, but concentrate federal power in the executive. In other words, each sought to adhere strictly to certain aspect of the Constitutional distribution of powers, while stretching others to achieve its desired political ends. (It goes without saying that neither had yet conceived of the bureaucratic state as a means of immunizing their policy preferences from popular opinion.)

The Jacksonians saw themselves as the logical extension of the “Spirit of ’98” and the Jeffersonian revolution of 1800, which is why, up until the current history purge, Democrats called their annual county dinners “Jefferson-Jackson Day” dinners.

Webster, never the leader of the Whigs but their most active campaigner in 1840, sought to turn the tables on them, relishing “beating the Democrats at their own game.” He campaigned on the idea that returning power to the legislature was fulfilling the Jeffersonian idea. The Democrats were appalled at his claim, but given the deep economic depression in 1840, nothing they said was likely to make much of an impression on the voting public.

From 70 to 2018

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Jewish, National Politics on July 20th, 2018

Sunday is the 9th of Av* on the Jewish Calendar. If Yom Kippur is universally recognized as the holiest day of the year, the 9th of Av, is unquestionably the saddest. It is the anniversary of the destruction of both the First and Second Temples. Jews around the world will mourn by fasting, reading the Book of Lamentations, and engaging in communal self-examination.

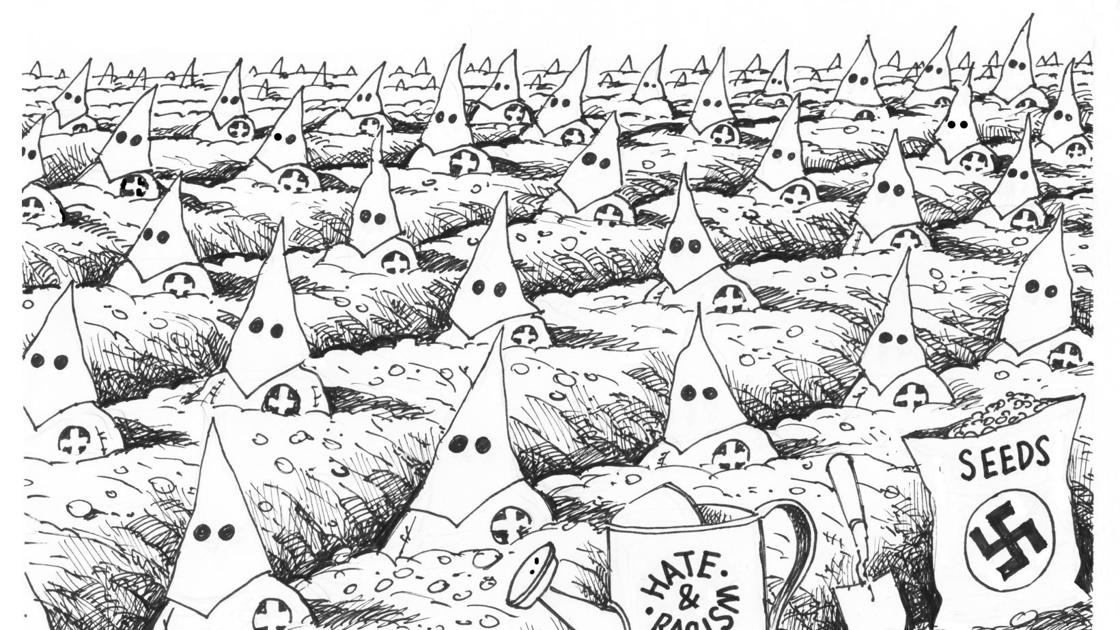

Self-examination for what, exactly? The Rabbis say that the Second Temple was destroyed as punishment for sinat chinam, among Jews, usually translated as “baseless hatred.”

But is any hatred truly baseless? Doesn’t even irrational hatred have some basis? Does anyone really hate someone else for no reason at all? Individuals have grudges, groups have rivalries, parties have different visions for the future. Sure, some of these may get out of hand, but are they ever totally baseless?

Rabbi David Fohrman discusses this at some length in his writing. In discussing the destruction of the Temple, the rabbis tell a story about what got the ball rolling. It’s the story of Kamsa and Bar Kamsa, and in it lies both the answer to our question, and a lesson for Americans today.

The story begins with a party. A wealthy man – he remains unnamed, perhaps a personal punishment – is throwing a party, and he sends his servant with an invitation to his friend, Kamsa. The servant, by mistake, brings the invitation to his enemy, a man named Bar Kamsa.

When the host sees Bar Kamsa at the party, he orders him to leave. Bar Kamsa, embarrassed at the mistake, asks to be allowed to save face. He’ll pay for his food. The host turns him down. He’ll pay for half the party. No, says the host, you must leave. Bar Kamsa will pay for the whole party, just don’t humiliate him in front all these people. No, insists the host, and forcibly escorts Bar Kamsa to the door.

What really stings Bar Kamsa, is that a number of prominent rabbis at the party saw the whole thing and who did nothing. Fine, the host was his enemy, thinks Bar Kamsa, I get that. He was being a jerk, but did I really expect anything better?

But the rabbis, it’s their job to encourage people to act with decency and respect, and they just sat there and did nothing. The longer Bar Kamsa thinks of this, the angrier he gets, until he finally decides to take revenge. He tells the Romans that the rabbis are plotting rebellion, manipulates events to make it look that way, and the whole thing snowballs into an actual revolt and the burning of the Temple. Bar Kamsa’s hatred has sown the seeds of Israel’s national destruction.

Fohrman notes that when we’ve been wronged, we react on two separate scales. One is how right we are, the other is how intensely we feel it. Was Bar Kamsa right? Of course he was. He humiliated in front of the cream of Jerusalem society, and the conscience of that society passively let it happen.

But on a scale of 1 to 10, how angry was he? Looks like 11. How angry should he have been? A four, maybe a five? After all, it’s just a party. By next week, everyone will have forgotten about it. Instead he decided to turn it into an international incident that ended up destroying the remnants of Jewish sovereignty for the next 1900 years.

Bar Kamsa, the host, and even to some extent the rabbis, had stopped seeing other people as whole human beings, and instead saw them as symbols. The host saw Bar Kamsa not as a person who was trying to redeem an uncomfortable situation, but as “enemy.” Bar Kamsa saw the rabbis as people who may not even have fully understood what was going on, but purely as instruments of his humiliation. The rabbis, for their part, didn’t see the host and Bar Kamsa as people acting out a personal drama in public, but as litigants in a dispute they couldn’t rule on. It’s much easier to get uncontrollably angry at a symbol than at an actual person.

Which brings us to today. Our social media personas can’t possibly reflect our full selves, and we react to others’ personas as though they were pure, true, authentic, and complete. For most of us, even for public figures, politics is a fragment of our lives. But we increasingly reduce each other to avatars of political movements, judging and punishing each other on that basis.

We react rather than taking time to think. We post with the fierce urgency of now, rather than the calm reflection of later. We use words designed for anger, and then find ourselves made angry not only by our own words, but by those of others. We go to 11 on the outrage meter and stay there, on everything, and we quickly make our disagreements about each other rather than about the thing we disagree on.

Increasingly, we think there is no escape, feel backed into a corner, raising the stakes of our politics. Each side believes that the other, given power, will use that power to take away our livelihoods and ruin our social lives merely for holding the “wrong” opinions. Each side believes that the other represents a metaphorical authoritarian gun pointed at our heads. Elected officials openly compare policy to the Holocaust, and call for the public harassment of political opponents – and it won’t end with high-level officials.

Since the election, the bulk of the hysteria has come from the Democrats and the Left. This is because they lost. However, given the reason that many voted for Trump, exemplified by Michael Anton’s famously persuasive Flight 93 Election article, I am reluctant to conclude that Republicans would have behaved much better had they lost. The Russians on whom so much attention is focused were careful to leave plenty of conspiratorial breadcrumbs on both sides of the street.

The Left is more responsible for the relentless politicization of every square inch of our public, private, and personal lives. But that doesn’t absolve anyone of trying to arrest this slide. Because we have a very clear message on the consequences of not arresting it.

And I have no idea how to put that back together.

*It’s actually the 10th of Av, but the fast and commemoration are put off for a day because the 9th falls on the Jewish Sabbath.

Bruce Catton and U.S. Grant

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, History on March 25th, 2018

Having finished Ron Chernow’s biography of Grant, I decided to go back to my library and re-read Bruce Catton’s shorter treatment of the subject, U.S. Grant and the American Military Tradition. Catton did most of his writing in the 50s and 60s, so some of the scholarship is dated, but most of his conclusions have held up.

More than that, Catton’s writing verges on the poetic, both summarizing and illuminating a subject with an economy of words I often wish I had. For instance, in describing frontier Ohio of the 1820s and 1830s:

Men who could do everything they chose to do presently believed that they must do everything they could. The brightest chance men ever had must be exploited to the hilt. And the sum of innumerable individual freedoms strangely became an overpowering community of interest.

When dissecting the rights and wrongs of secession, its present-day defenders (who do not defend the institution of slavery, it should be emphasized) tend to focus on the clinical, legal aspects of the matter. Catton captures what they miss, and why the North and especially the West was willing to fight:

Against anything, that is, which threatened the unity and the continuity of the American experiment.

Specifically, they would see in an attempt to dissolve the Federal Union a wanton laying of hands on everything that made life worth living. Such a fission was a crime against nature; the eternal Federal Union was both a condition of their material prosperity and a mystic symbol that went beyond life and all of life’s values.

On the post-Shiloh commanders:

McClellan, Halleck, and Buell, then, were the new team, and that hackneyed word “brilliant” was applied to all three. The Administration expected much of them. It had yet to learn what brilliance can look like when it is watered down by excessive caution and a distaste for making decisions, and when it is accompanied every step of they way by a strong prima donna complex.

And on how Americans view war. Catton believes it goes a long way towards explaining why Grant – representative of his people – was doomed to substantially fail at the big post-war task of Reconstruction and restoration:

…the will-o’-the-wisp again, recurrent in American history. Victory becomes an end in itself, and “unconditional surrender” expresses all anyone wants to look for, because if the enemy gives up unconditionally he is completely and totally beaten and all of the complex problems which made an enemy out of him in the first place will probably go away and nobody will have to bother with them any more. The golden age is always going to return just as soon as the guns have cooled and the flags have been furled, and the world’s great age will begin anew the moment the victorious armies have been demobilized.

Sound familiar?

Catton was not, of course, infallible. He had this to say about President-Generals, whose training is to treat Congress as supreme, the executive as the instrument of Congress’s declared war aims:

It made it inevitable that when he himself became President he would provide an enduring illustration of the fact that it can be risky to put a professional soldier in the White House, not because the man will try to use too much authority in that position but because he will try to use too little.

Catton wrote these words in 1954, with full awareness of who was then president. But history doesn’t bear out his fear, entirely. Washington maintained a strong sense of the office’s limitations, but worked to strengthen both the federal government and the executive. Neither of the two previous Whig presidents – both generals – lived long enough to have much impact in the office. And Eisenhower was working with an already-stronger executive, which he worked to professionalize, treating his cabinet a little like a corporate boardroom of competing ideas.

He differs with Chernow on a few points, and Catton is somewhat better at drawing connections. Catton considers the Santo Domingo treaty not merely ill-advised but actually corrupt, for instance. Both note that Grant manumitted the one slave he ever owned as quickly as he could (a gift), but only Catton points out that Grant did so even though he could really have used the money from a sale at that point in his life.

Catton is also harder on the Radical Republicans, and somewhat more forgiving of Andrew Johnson, than Chernow is, possibly because Catton was unaware of the postwar wave of white supremacist violence that swept over much of the Deep South. He argues that the Radical Republicans were at least as interested in using blacks as a means to political power as they were in their welfare – not the last time that would happen in American history. Catton also claims that Johnson adopted Lincoln’s view of postwar reconciliation, where Chernow states that Johnson adopted a softer line through misbegotten racial solidarity. Whether this is from cynicism or greater political savvy, or from both, it’s hard to know.

Some Short History Reading Lists

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, Cold War, Constitution, History, Revolutionary War on January 21st, 2018

We were over at a friend’s house for lunch this Shabbat. Knowing that 1) I have a lot of history books, and 2) I tend to read them, he was kind enough to ask me for some reading lists about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Cold War. “I haven’t had much luck with fiction, so I’m trying to round out my history.”

Here’s what I sent him. These aren’t intended to be college syllabuses, or comprehensive. They’re books that I have and leafed through, or that I’ve read. I’ve tried to vary them by author. I could have had the entire Revolutionary War list by Joseph Ellis, the whole Civil War list by Bruce Catton, but what’s the fun in that? My library, while large by 19th Century standards, is limited by the size of the house. Had I fewer books, I would paradoxically have more room for them. But it’s a good list, enough to cover some key points, get an overview, or just when your appetite for more.

American Revolution

For a decent overview of the war as a whole, Liberty by Thomas Fleming isn’t bad. I think it was originally written as a companion book to a PBS series, but it’s good in its own right. For a deeper examination of the issues around the Revolution and the war, and how the Founders handled them, American Creation by Joseph Ellis is recommended.

We all know of Washington Crossing the Delaware; David Hackett Fischer has written a great in-depth review of the events surrounding that crossing and subsequent battles, and how they set the stage for the rest of the war, in Washington’s Crossing.

And for well-researched discussions of adoption of the two primary founding documents – the Declaration and the Constitution, Pauline Maier’s American Scripture and Ratification give surprising insights into what people were thinking at the time.

The Founders lived on into the post-Revolutionary era, and had a second act right after the Constitution in 1787, so some bios are in order. Richard Brookheiser’s short Founding Father is a fine thumbnail bio of Washington; for something longer Ron Chernow has bios of both Washington and Hamilton. And David McCullough’s John Adams is what the PBS series was based on.

Having come this far, read about 700+ pages about the early Republic, when were getting ourselves established, with Gordon Wood’s Empire of Liberty. I’m reading it now, and pretty much every chapter has some surprise or another.

Civil War

For the lead-up to the war, and how we got to the point of secession and war, William Freehling’s long, two-volume The Road to Disunion is among the best.

Much of the same material is covered in the first volume of Bruce Catton’s very readable and shorter three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War. These are The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat. I would recommend anything written by Catton on the Civil War.

Also excellent is Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson. As a guide to Lincoln’s war, what the events looked like from DC, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals is magnificent.

Cold War

This one is tougher, because it covers decades, not mere years, so the politics, military, and technology changed substantially from 1948 to 1989. I’ve picked out the books I have and have read that do a good job talking about the Cold War. My library is heavier on the spy stuff, but there was a lot of spy stuff.

Witness by Whittaker Chambers is indispensable. He starts out as a Communist, and then converts over to the good guys, and was a key player in one of the great Cold War controversies, the Alger Hiss case. Nixon’s rise to prominence began with this case, and the left never forgave him for being right.

The Great Terror, is one of the best books about Stalin’s Russia, by one of the best chroniclers of the 20th Century, Robert Conquest.

The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn is recognized as the best insider account of the Soviet punishment system.

Berlin 1961 by Frederick Kempe covers the building of the Berlin Wall.

Merchants of Treason by my friend Norman Polmar and KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents are old now, but a good guide to how to the KGB operated in the day, and how the Russians still operate today.

There’s also a vast literature of spy fiction, from Len Deighton’s devastating Game-Set-Match trilogy to John LeCarre’s oeuvre (start with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy).

That’s enough to keep you busy for a few years. So what are you still doing on this page?

The Eternal Tax Debate – Lessons from the 1920s

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Economics, History, Taxes on November 28th, 2017

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

Growth was too low, as the post-war economy struggled to recover from a recession.

The new president and his treasury secretary were convinced that a serious package of tax reform could unleash much-needed growth.

And they had a plan. The top marginal rate was too high; it should be in the 20s. The estate tax drove down the price of assets and should be eliminated. There were too many special carve-outs. Tax-free interest on municipal bonds was diverting capital from private enterprise.

To be sure, not all the proposals were for lowering tax rates. The secretary wanted a capital gains rate higher than the income tax rate.

But the political situation was working against them. Their own party was split, and they ran into opposition not just from the openly Progressive party, but from the Progressive wing of their own party, which included the Senate Majority Leader. Opponents of the administration’s plans pointed out that the bulk of the benefits would go to the wealthy, including the treasury secretary himself.

Opponents argued that federal revenue would plunge; the treasury secretary persuaded the president that unlocking capital would cause an economic boom and swell the tax take. They argued for a top tax rate around 40%.

Conservatives believed that nearly everyone should pay something. Progressives disagreed.

Scandals, distractions, and Congressional investigations also sapped the president’s attention and political capital.

The president and the treasury secretary also complained that the time it was taking to pass a bill was extending the experimentation of the previous Democratic administration, and the destructive uncertainty that accompanied it. Passing something, they argued, even if it didn’t meet their exact specifications, would be more important than dithering and passing nothing.

Eventually, the treasury secretary would get his tax reform package, mostly on his own terms, and he and the president would see federal revenue leap upward as a result. (He wouldn’t get everything; the secretary wanted a top marginal tax rate in the 20s; Congress seemed more inclined to something around 40%.)

The treasury secretary was Andrew Mellon, and it would take another round of elections, the death of President Harding and the accession of President Coolidge to make it happen.

Ironically, these tax reform plans weren’t originally even Mellon’s. Wilson Administration Treasury Department bureaucrats developed them after the war. They hoped to transform federal tax policy from an ad hoc patchwork into a permanent, systemic tax regime, the emphasis being on permanent.

Ninety years later, we are still having substantially the same discussions, on substantially the same terms. Does that mean that the Progressives were successful? Perhaps, and perhaps not.

Mellon dubbed his approach “scientific taxation,” designed to maximize revenue while minimizing the tax burden. But the fact that we’re still picking over many of the same details in 2017 suggests that the science is far from settled.

Analogies to past epochs in American history are not currently commonplace. Some see a darker replay of the late 60s and early 70s. Others, more alarmist, see a replay of the pre-Civil War 1850s divide. Those comparisons rely more on the social atmosphere than on specific issues.

It’s unusual to see a policy debate stagnating, with the same arguments, over roughly the same issues, for nearly a century.

To some degree, this is the peculiar result of its being both narrow and central. The income tax itself cuts across numerous persistent philosophical and political divides.

Superficially, the room for policy debate is narrow: after 100 years, the personal income tax’s basic structure – progressive rates with special-interest credits and deductions – remains essentially the same.

But the tax’s seeming simplicity masks endless room for mischief, and therein lie the complications.

The personal income tax contributes nearly half of the federal government’s annual revenue; combine it with the payroll tax, and just under 5/6 of federal tax revenue is based off of personal income.

Lowering or raising rates will affect not only an individual year’s deficit, but also the economy’s rate of growth and attendant opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, and employment. The overall take calls into question the size of government as a whole.

The amount of progressiveness, both the top rate and the number of people who pay nothing, raise the ill-defined but politically potent question of “fairness.”

In policy terms, each deduction or credit raises the question of whether or not the government should be supporting or suppressing the industry or choice involved. What gets exempted raises the question of privileged institutions like university endowments or state and municipal debt and taxes.

In fact, the whole structure implicitly accepts the idea that it’s the federal government’s job to support or suppress certain economic decisions. That credits and deductions can only be taken under certain circumstances open the door to micromanaging those decisions.

And every one of these credits and deductions immediately acquires a non-partisan, which is to say bipartisan, constituency, either because it helps someone or hurts their competition. Thus are we treated to the spectacle of otherwise conservative Republicans in New York, California, and New Jersey defending national taxpayer subsidies for their expansive state and local governments.

That goes a long way toward explaining why we’re stuck in the same debate.

And unfortunately, why we probably will be for a long time.

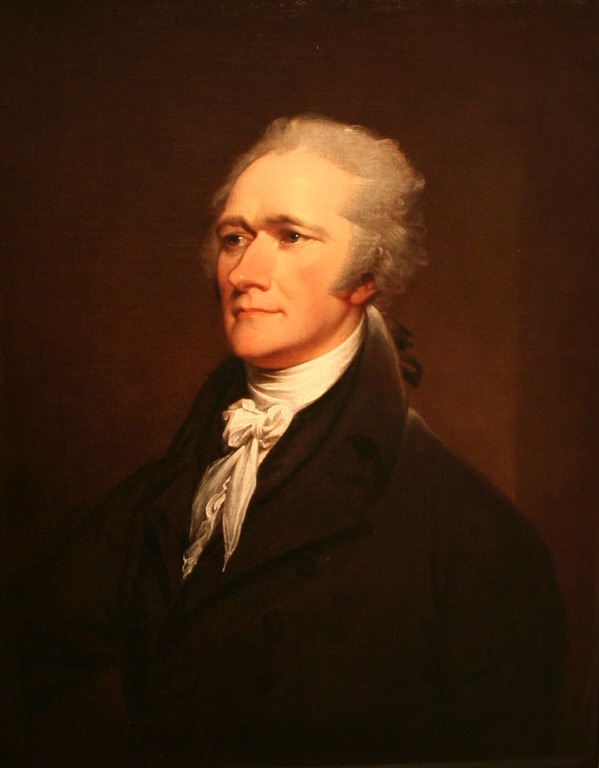

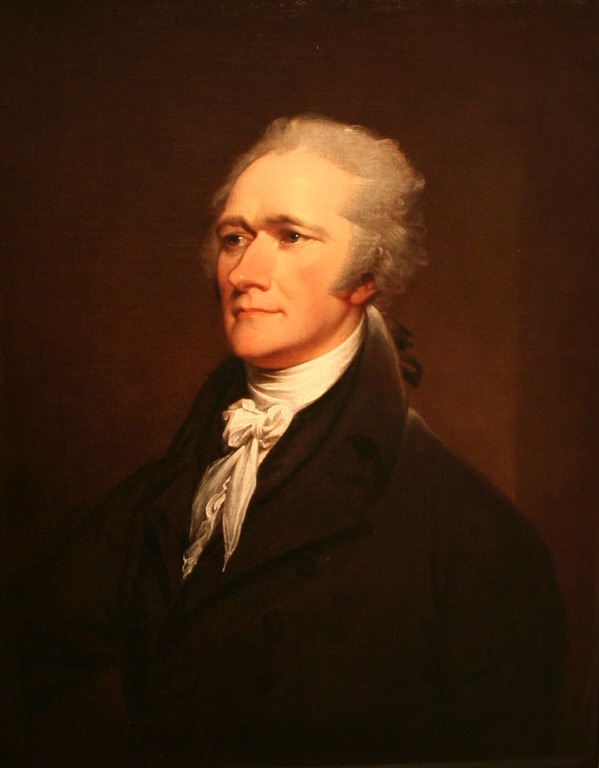

Hamilton’s Productivity

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 22nd, 2017

In his biography of Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow marvels several times of Hamilton’s capacity for work. He wrote the bulk of the Federalist Papers, sometimes turning out as many as 5 in a week. When his opponents in Congress wanted to try to hang him on unfounded corruption charges, for instance, they demanded that he produce voluminous reports on short deadlines. They underestimated him. On p. 250, Chernow describes how Hamilton was able to do this:

Hamilton’s mind always worked with preternatural speed. His collected papers are so stupefying in length that it is hard to believe that one man created them in fewer than five decades. Words were his chief weapons, and his account books are crammed with purchases for thousands of quills, parchments, penknives, slate pencils, reams of foolscap, and wax. His papers show that, Mozart-like, he could transpose complex thoughts onto paper with few revisions. At other times, he tinkered with the prose but generally did not alter the logical progression of his thought. He wrote with the speed of a beautifully organized mind that digested ideas thoroughly, slotted them into appropriate pigeonholes, then regurgitated them at will.

Both the organized mind and the regurgitation are harder than they look. They both require patience, training, and discipline. Yes, he was writing at a different time, when repeating arguments didn’t mean chewing up half of your allotted 700 words. Length was never an issue, and Hamilton, being Hamilton, was brilliant enough that neither was publication or readership. But I notice it when favorite columnists of mine no longer have anything new to say, and part of my own lack of production is from a desire to say something new each time, rather than even mentally cut-and-paste from previous efforts. Contrary to popular opinion, it takes patience to repeat yourself.

This goes hand-in-hand with having an organized mind. One wants to be able to assimilate events and ideas, and to respond to them. But there’s a concomitant risk of building a system and fitting everything into that system. One’s thinking becomes rigid, rather than supple and responsive. You see this all the time with people who reduce all political arguments to one or a handful of principles – everything becomes confirmation of those few underlying ideas, but then all arguments return to those same few ideas. Discussions become stale, because it’s more comfortable to have the discussion you’re used to having.

Breaking News From 1798

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Political History on October 18th, 2017

I may be the last person on the planet to have read Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. I’ll certainly be digesting it for a while.

Among Chernow’s contributions is a detailed discussion of the American political climate, during the Washington and Adams administrations, when the bulk of Hamilton’s contributions to the nascent government were made. It’s also when we saw the emergence of the first real political parties in history, parties committed to more than the mere attaining and retaining of power, but also to rival economic and political theories.

Today, we’re used to the stability of the two-party system, but at the time, they were not only a novelty, but a bit of a shameful one at that. The Founders had wanted to avoid factions, or parties. The new parties were not only organized around ideas, but also around the personalities of their leaders. This led to a curious combination of personal touchiness, mutual misunderstanding and hostility, and denial that it was going on at all.

From Pages 391-92 of the softcover edition:

The sudden emergence of parties set a slashing tone for politics in the 1790s. Since politicians considered parties bad, they denied involvement in them, bristled at charges that they harbored partisan feelings, and were quick to perceive hypocrisy in others. And because parties were frightening new phenomena, they could be easily mistaken for evil conspiracies, lending a paranoid tinge to political discourse. The Federalists saw themselves as saving America from anarchy, while Republicans believed they were rescuing America from counterrevolution. Each side possessed a lurid, distorted view of the other, buttressed by an idealized sense of itself. No etiquette yet defined civilized behavior between the parties. It was also not evident that the two parties would smoothly alternate in power, raising the unsettling prospect that one party might be established to the permanent exclusion of the other. Finally, no sense yet existed of a loyal opposition to the government in power. As the party spirit grew more acrimonious, Hamilton and Washington regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature.

One last feature of the inchoate party system deserves mention. The emerging parties were not yet fixed political groups, able to exert discipline on errant members. Only loosely united by ideology and sectional loyalties, they can seem to modern eyes more like amorphous personality cults. It was as if the parties were projections of individual politicians – Washington, Hamilton, and then John Adams on the Federalist side, Jefferson, Madison, and then James Monroe on the Republican side – rather than the reverse. As a result, the reputations of the principle figures formed decisive elements in political combat. For a man like Hamilton, so watchful of his reputation, the rise of parties was to make him ever more hypersensitive about his personal honor.

The parallels between the politics of that day, when parties were being formed, and today, when they have been structurally weakened and are in flux, should be obvious. The party establishments and the administrative state mitigate some of the effects, but there’s no question that election laws have neutered party back-rooms and allowed anyone to run under a party banner. The move towards open primaries further erodes party discipline. Each party increasingly sees the other less as principled opposition and more as a conspiracy bordering on organized crime. And there is no question that the Bush and Clinton dynasties, along with the personally prickly Obama and Trump, have personalized presidential politics to a degree we’ve not seen in a while.

Over the last several presidential elections, people have called attention to the vitriolic nature of political campaign rhetoric, if not (until 2016) by the candidates themselves, then by their surrogates and supporters. As often, people have trotted out some of the truly vicious things said in the campaign of 1800. With a somewhat broader view, that similarity seems less a coincidence and more like the product of a common cause.