Archive for February, 2021

Purim, Esther, and Us

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 26th, 2021

I’ve always thought that the Book of Esther would make a terrific movie. It’s got palace intrigue, public politics, massive stakes, and the fate of empires and the Jewish people hang in the balance of the actions of fully-drawn characters.

That movie has yet to be made, and the oft-cited One Night With the King surely isn’t it, despite the casting of John Rhys-Davies as Mordecai. I mean, it’s a terrible movie, and I had to sit through it twice (don’t ask), and literally the only thing I remember of it was this speech that he gives:

“Do not imagine to yourself that you will escape in the king’s house from among all the Jews. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and rescue will arise for the Jews from elsewhere, and you and your father’s household will perish; and who knows whether it was for a time like this you became queen?”

Of course, Davies had better writers for this speech, since it’s directly from the Book of Esther itself.

Rabbi David Fohrman in his The Queen You Thought You Knew, notes that “if you remain silent” in Hebrew consists of a doubled-verb, for emphasis, and draws a connection to the only other time in Tanach that verb is doubled. It comes in a discussion of when a man can nullify a vow that his wife has made. He can either immediately nullify it, or he can immediately confirm it.

But if he tries to exercise a sort of “pocket veto” by actively remaining silent and doing nothing, well, that’s not an option. It becomes valid over his silence, his deliberate effort to pretend that no vow has been taken. Remaining silent in this case is kind of a coward’s way out, but it makes no sense – either the vow is valid or it’s not.

Esther, similarly, doesn’t have the option of silence and doing nothing. She either goes along with what’s happening or she tries to stop it. Doing nothing is tantamount to letting the genocide of her people happen – she can’t pretend there’s no mortal danger, even though nobody at the palace knows she’s Jewish.

And so, she doesn’t.

Rather than being seduced by the trappings of power and comfort and taking a pass, and not knowing what’s going to happen, she confronts her fears, concocts a risky plan, and runs the gauntlet of guards and idols to go visit the king in his private chamber. She has no idea if the guards have been told to not let anyone in. She has no idea what the king’s reception will be. She doesn’t really have any idea if her plan will work, although it’s a good plan and she’s tried to load the dice as well as she can.

The lesson for today, for each of us not only as Americans but also in the Jewish community, could not possibly be more obvious. Our current Jewish leadership is in disarray, unwilling to confront rising anti-Semitism as long as it comes from its preferred political party, instead pretending there’s no danger.

We know who our Esther is supposed to be. Do we have a Mordecai to slap some sense into them and remind them of their obligations?

Albion’s Seed

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 21st, 2021

Our American history book club’s official selection was The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America, 1600-1675, by Bernard Bailyn. But since I’m ridiculously competitive, I also read the additional 900 pages of David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed, which had come highly recommended by a number of friends.

Fischer traces the British settlement of North America to four main waves of migration, originating in four different regions in Britain at four different times, bringing with them four distinctive folkways that proved to be surprisingly durable here in the New World. Their social and political attitudes, and their distinctive interpretations of liberty, set the tones for the four different regions they settled, persisting often into the 20th Century, and the interplay of the four, with the occasional dominance of one or another, greatly affected national politics.

Fischer identifies four main English folkways that came to dominate what would become the United States. These are the Puritans who came here from 1620-1650, settling in New England; the Quakers and sympathetic (mostly) German Pietists who came here from 1675-1700; the Virginia Cavaliers, sympathetic to the Crown in the English Civil War, arriving in the mid-1600s, and the Anglo-Irish or Scots-Irish who settled the backcountry, coming in a series of waves from 1700 to about 1775.

Each of these migrations came from fairly specific locations back in England: the Puritans from East Anglia, the Virginians from Wessex and Mercia, the Quakers from the north Midlands, and the backcountry from the Border counties near the England-Scotland line. While none of the sections was settled exclusively from those areas, each of them drew at least 60% of their populations from them.

Fischer’s genius here is two-fold. First, he traces back distinctive cultural features to the groups’ regions of origin in England, including clothing, house design, language, relations between age groups and between the sexes, and so on. Many elements that historians had assumed were developed here on this side of the Atlantic in response to the Indians they encountered, or the geography where they settled, were actually brought over. Even terms such as “hoosier” or “redneck,” the origins of which frequently are the subjects of social media arguments and bar bets, were already in use back in England.

The fact that generations of historians continued to tell what amount to just-so stories about the layout of the Puritan house or village, for instance, should be profoundly disturbing, and cause for great skepticism concerning any generally accepted historical consensus.

The second great insight here is the persistence of these cultural differences, which were often the actual reasons for political differences we have traditional explained by other factors. A friend of mine who teaches American colonial and Revolutionary history points out that the best way to approach the colonial period, especially up to about 1750, is to treat the various regions as more or less independent entities, with occasional interaction.

Fischer himself takes it a step further, pointing out that the four folkways didn’t just operate independently before the Revolution, they actually detested each other, sentiments which continued well into the 19th Century. The Puritans saw the Virginians as dissolute and immoral. The Quakers saw the Puritans as tyrannical in their own way. And all three more or less looked down on the Border-country immigrants, which the Scots-Irish returned in at least equal measure.

Their political institutions also came into conflict when they came into contact at the Constitutional Convention. The conflict between the Virginia and the New Jersey plans for the Senate is usually painted as purely as dispute between the large and small states. But Fischer argues that it was at least as much a conflict between Puritans who were used to frequent elections and town meetings, and Virginia aristocrats who were used to controlling the paths to higher power. Massachusetts, a large state, opposed the Virginia Plan as presented.

Likewise, the Puritan idea of “ordered liberty” meant a strong government enforcing morality and limiting destructive dissent. It came in for a rude awakening when the other three folkways turned on it after the John Adams administration, and again after that of his son, John Quincy Adams.

Fischer deserves great credit here for the book’s organization and layout. First of all, he doesn’t stint on maps. You want to see where in America people settled, where in England they came from, and in what numbers, and he’s always got a clearly-labeled, clearly-shaded map for you. I cannot stress enough how frustrating it is to read a history book that skimps on maps.

Second, in each of the four main sections on the four folkways, he’s covering about 20 different aspects of their culture and society. It would have been easy – and lazy – to write each as a completely independent section, leaving the reader who’s working his way through the marriage section on the backcountry to remember what he read 600 pages ago about Puritan marriage customs. But he doesn’t do that. He frequently refers back to the earlier sections, making it easier to compare them all as you read.

The last chapter attempts to trace the post-Independence effects of these four folkways in the country’s presidential politics. It works reasonably well through the Virginia Dynasty, the Age of Jackson, the Civil War, and even the Gilded Age, up until Wilson’s election, after which the more one knows about the politics of the period, the more apparent how selective the supporting data becomes.

The dangers of this sort of analysis when applied to individuals become apparent in the few pages devoted to the country’s WWII leadership. Roosevelt, despite his Dutch name, was of largely Puritan stock, giving a clear moral tone to the war effort; Patton, whose family was Scots-Irish, loved fighting, and loved fighting from the front, but had problems controlling his own temper; Eisenhower, from a German Pietist background, went to West Point for the free education, never saw combat in his career, and sought to win the war with minimal casualties; Marshall, born in Pennsylvania of a family from the old Virginia aristocracy, was born to command, took on tremendous responsibility with tremendous self-restraint, and suffered neither fools nor insubordination. The stereotypes work for these four, but the weakness is in the millions for whom the stereotypes were no longer working.

But excellent books often overstate their cases. Fischer is still able to trace distinctive, persistent political elements back to the original culture created by each folkway. Virginia, for example, governed for many decades by Governor William Berkeley, early on had concentrated power and lower levels of literacy. The governing Cavaliers saw no reason why the populace at large should go to school, nor why independent presses with potentially dangerous ideas should be allowed to operate. And so lower literacy levels continue to persist, even to this day. Likewise, New England and the northern tier of states remain bastions of aggressive state-sponsored moralism, and the backcountry border people are clearly visible in J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy.

None of the four regions was, itself, a little proto-America, nor was it, in itself, representative all of England during the whole of 1600-1750. Fischer’s insight here is to show how much they brought over of what they became, and how their slow mixing and interaction formed what we are today.

The Economy Has No Pause Button (3)

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 20th, 2021

Aside from the wreckage to our small businesses, restaurants, and hospitality businesses, the Democrat shutdown of the economy and the imposition of Wuhan coronavirus work rules have done their worst work on our supply chains. These are the raw materials, components, and wholesale businesses upstream of the assemblers and retailers, that consumers never see. Unless they happen to work in those fields, in which case they see them all too immediately.

But they see the effects of these failures when they have to wait weeks or months for appliances and other products that were formerly readily available.

Economic surveys out of three Federal Reserve districts show these disruptions to be ongoing, if not worsening, a year into the largely-manufactured economic crisis in response to the very real virus.

The New York Fed reported last week that “The surveys also found that supply disruptions were widespread, with manufacturing firms reporting longer delivery times and rising input costs, a likely consequence of such disruptions.” Half of the businesses surveyed said that they had experienced supply disruptions this year, while over 25% said those disruptions had affected their businesses either moderately or substantially.

This confirms earlier reports from both the Dallas Fed and the Kansas City Fed (which has jurisdiction over Colorado). The Dallas Fed survey reported increases in Unfilled Orders, Delivery Time, and Prices Paid for Raw Materials. All of those would indicate supply line pressure. The Tenth District Survey reported decreases in inventories and increases in input prices, which would indicate difficulty in keeping items stocked.

When the shutdowns started, advocates assured us that things could be started up easily, that disruptions would be short-lived, and that people warning otherwise were motivated either by greed or politics. Like most progressive assumptions, they’ve proven to be wrong, and at great cost.

Woke Comes For Math

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 16th, 2021

The three women pictured above were pretty good at math. They helped the space program do the calculations that got us to the moon. They were the subject of the film Hidden Figures, nominated for Best Picture the same year that La La Land Moonlight won. For those of you keeping score at home, that was a scant five years ago.

They were remarkable not only for their brains, but also for having overcome both racism and sexism in mid-century Tidewater Virginia. There was no suggestion that, at any point in their mathematical educations, the material was dumbed-down or reorganized for them because they were black or because they were women. There was no suggestion that it needed to be. Grading their school work on a curve would have cheapened their achievements; doing so with their professional work would quite possibly led to men dying in space.

Indeed, at Virginia’s physics and math departments, where I was an undergrad in the 1980s, we were relieved that the standard of truth and rigorous examination required by the physical sciences and by mathematical reasoning rendered them impervious to what was then becoming known as “political correctness.”

It would take the brains of 2020s education professionals to promote such an absurdity.

Pictured below is the layout of a course on “dismantling racism in mathematics instruction.” It is being promoted by the state of Oregon’s education department.

You will note that being expected to work on your own, to show your work, and to get the right answer are considered elements of “white supremacy culture.” Grades are racist. Addressing mistakes is considered bigoted.

None of this is true, of course. Math problems have a right answer, especially those problems students are likely to see in high school. Showing your work is how you prove you understand the concepts, and how you help the teacher identify where you’ve gotten off-track if you end up in the Sea of Cortez rather than the Sea of Tranquility. Students can help teach each other, but eventually each has to understand the material on his own. And for some students, grades can be a powerful incentive to hunker down and do the homework. If these aren’t universally, true, there’s no reason to think they have anything to do with race.

Some of these elements are just part of the merry-go-round of pedagogical debate, dressed up in woke clothing to give it the moral high ground in order to dissuade dissenters. It is considered racist to “prefer procedural fluency over conceptual knowledge.” I grew up in the 1970s and was subjected to this garbage, getting lots of partial credit for “getting he idea right” even when I was sloppy in the execution. Teachers were following a fad, not trying to correct for decades of racism in my almost-all-white elementary schools, but it still contributed mightily to poor attention to detail that I struggled for many years to correct.

The one elements that seems to have some merit – that English-language proficiency shouldn’t be confused with technical proficiency – is also completely disconnected from race. Bilingual education may be foolish, counterproductive, and ultimately ghettoizing, but since immigrants can be of any race, it’s not racist.

Lost on the people with doctorates who designed this nonsense is its own inherent racism, the idea that somehow poor kids non-white students are too stupid to get to the right answer and to show how they got there, or to get there on their own, or to progress from one skill to another. Far from helping these kids, it risks condemning them to a lifetime of mathematical illiteracy by adding to the obstacles they have to overcome.

Mrs. Johnson, Mrs. Jackson, and Mrs. Vaughn would probably have something to say about that.

Mank, And Taking Things Seriously

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 15th, 2021

On the online recommendation of a friend, I watched David Fincher’s movie Mank over the weekend. It’s the story of dissolute Herman Mankiewicz as he works to finish the screenplay to Citizen Kane, after Orson Welles has cut a month off of his three-month deadline.

The central question of the film is why Mankiewicz is writing Kane as a takedown of William Randolph Hearst, when he knew both Hearst and Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies, socially, and was a frequent guest at San Simeon. That’s a question for another post, because it may contain some spoilers.

Part of what makes this movie about Hollywood work is that almost all the main characters are actual historical Hollywood figures, most of them titans of the industry’s golden years in the 30s. Among them is Irving Thalberg, who now has a annual Oscar named after him. Thalberg began life as a writer, but by this time was Louis B. Mayer’s production supervisor at MGM.

Early in the movie, we get a sense of what Mankiewicz thinks of Hollywood, when he sends a telegram to a writer friend of his inviting him out to the coast: “There are millions to be made here and your only competition is idiots.” In a confrontational scene in Thalberg’s office, Mankiewicz resorts to wit and clever condescension. This provokes Thalberg to retort:

I know what I am, Mank. When I come to work, I don’t consider it slumming. I don’t use humor to keep myself above the fray. And I always go to the mat for what I believe in. I haven’t the time to do otherwise. But you, sir, how formidable people like you might be if they actually gave at the office.

A later generation of writers would give at the office, both for better and for worse.

It’s not a particularly original observation to say that social media has encouraged this “court jester” tendency in too many of us, myself included. I’ve often had the idea of FB as a big, multithreaded cocktail party with lots of simultaneous conversations going on. It’s easy to drop in, see where things are, lay down a laugh line, and stick around for a moment to enjoy the laugh reacts.

That’s not always an inappropriate thing to do. Sometimes the conversation itself isn’t very serious. And I happen to best enjoy humor that draws connections between unexpected threads. Maybe there really is something there that’s food for thought.

But then you actually have to go and do the thought. Leaving the connection unexplored is lazy and it’s cheating. A joke itself may be the product of some thought or some intuition or even some analysis. Sometimes it’s an excellent way to quickly encapsulate an entire worldview. But unless you’ve put in the work, it’s a dead end, it’s a lot of icing without the cake.

Posting rewards cleverness, writing rewards thought.

It’s part of the reason that I’ve begun writing again here on the blog. Yes, I want to escape the tyranny of having Facebook own all my writing on subjects as they come up. But it’s also a medium that’s more conducive to thinking things out and considering consequences and implications. I don’t necessarily want to be a humorless Irving Thalberg, but at the end of the day, there’s more substance to a Joseph Epstein than a Henry Mankiewicz.

We’d all be better off stretching those muscles more often when it comes to serious subjects.

Biden Kow Tows

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 14th, 2021

The Biden Administration, less than a week after taking office, has reversed a proposed Trump Administration rule that would have required colleges and universities to disclose their operating agreements with Confucius Institutes.

The Institutes are popular with US schools because the Chinese government picks up the tab and provides the teachers and materials, while the university or college need only provide the venue and the students. They give colleges a turn-key operation that teaches Chinese language, history, and culture, often where there was no such offering available before.

Of course, that also comes with strings – the Chinese get to dictate the curriculum. The teachers are also skilled at deflecting, ignoring, or marginalizing uncomfortable questions about Uyghur genocide, Hong Kong suppression, Tibetan imperialism, or designs on Taiwanese democracy.

And with so many Chinese students attending US colleges, the Institutes provide a convenient base from which to keep eyes on them. One of the selling points of letting us train the next generation of Chinese scientists and engineers is that they’ll take home their exposure to US freedoms, leading to domestic discontent among the Chinese middle class with the CCP’s repression. Spies at the CIs aim both to keep close watch on the Chinese students here, and to remind them that they usually have vulnerable family back home.

All of this led the Trump Administration both to its belated effort to require schools to disclose the terms of their arrangements, and to its designation of CIs as Chinese foreign missions.

Biden’s move comes at a time when these institutes have come under intense scrutiny both from the US government and from students themselves, leading schools to begin closing them. If Biden’s foreign policy team tries to relieve that pressure, it could extend their presence on US soil.

Worse than that, it signals an unwillingness to interfere with the ongoing Chinese purchase of the US elite institutions, and the creation of battalions of progressive advocates and apologists for the Chinese system here in the US.

Infinity

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 12th, 2021

A few days ago, The Atlantic carried an article by physicist and writer Alan Lightman (“It Seems I Know How The Universe Originated“), about the infinite, and about Andrei Linde’s refinements to the Big Bang Theory of the universe. It’s about that, but also about much else.

I had first read of Linde’s theories many years ago in Omni magazine, but in Omni, it was often difficult to separate actual science from pseudo-science or speculative fantasy, even when it was labeled science. So I filed them away. Lightman’s is the first article that explained Linde in a way that allowed me to understand him. Here’s the key paragraph:

A strange aspect of quantum physics is that energy and matter can suddenly appear out of nothing for short periods of time. If you could examine space with a strong enough microscope, you would find that it is constantly fluctuating, seething with ghost-like particles and energies that randomly appear and disappear. Quantum phenomena are normally apparent only in the tiny world of the atom, but near t = 0 the entire observable universe was smaller than an atom. If at a certain point in the infant universe sufficient scalar field energy had materialized, its repulsive gravitational effect would have caused space to expand so rapidly that an entire universe would have been created. Since such quantum fluctuations would have been going on at random places and times—this is the “chaos” in Linde’s eternal chaotic inflation theory—new universes would have been constantly forming.

“In this vision, universes endlessly spawn new universes, each with its own Big Bang beginning. Our t = 0 would not be the beginning of space and time in the larger cosmos, only in our particular universe.” New universes would have been constantly forming, and presumably, still are forming. Forever.

Left mentioned but undiscussed are the theological implications of such a universe. Judaism and the monotheistic religions have tended to posit that only God is infinite, and that the Universe has a definite beginning and end. This stands in rough opposition to Aristotle’s assertion that the Universe itself is infinite. I realize this is a simplification, but it’s a reasonably accurate one. Even if the Rabbis admitted that God created many universes before ours, only God Himself remains infinite. I’m unsure if they entertained the possibility of universes after ours.

A few months ago, I watched most of a video of the Life of the Universe, the vast majority of which consisted of relentlessly increasing disorder and darkness, where life took up a vanishingly small portion of the very beginning of time. Something like 75% of Time was taken up with things like the last black holes evaporating. Linde’s modification of Guth’s Inflationary Model offers, in some sense, a way out of this, that is perhaps also consistent with an infinite God presiding over the creation of many universes rather than just one.

Lightman mentions in several places the role that interpretation plays in theoretical physics, something not always understood by non-physicists, but which became readily apparent to me even as an undergrad at Virginia.

Yet Linde’s bulbs follow as logical consequences of certain mathematical equations. As Linde would acknowledge, those equations are also works of the human imagination, models of reality instead of reality itself. Linde’s ideas are at once visionary and grounded in logical thinking. Although mathematically proficient in the manner of all theoretical physicists, Linde described himself to me as more intuitive than technical, a Steve Jobs more than a Steve Wozniak.

….

Other scientists with equal brainpower but more cautious dispositions have not ventured nearly so far in their theories of the world. The equations are the equations, but they must be imagined and interpreted in the human mind, a particular human mind, a complex universe itself, endlessly variable in its quirks and possibilities.

It’s one thing to derive an equation, something else again to understand and imagine its implications in the real, physical universe. It is something else again to distinguish between those implications that are observable – and therefore provable or falsifiable – and those that must remain speculative. Theoreticians who have a gift for derivation don’t always have the intuition for interpretation.

As with almost everything Lightman writes, read the whole thing.

The Play’s The Thing

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 10th, 2021

The recent demise of Christopher Plummer led to a lot of postings of Edelweiss, or other clips from The Sound of Music, the movie for which he was best-known, even if he was at best ambivalent about the role.

It led me to go back and listen to the Broadway cast album which included Mary Martin (not Julie Andrews) and Theodore Bikel (not Mr. Plummer). And tucked in there are two songs that were dropped from the movie, “How Can Love Survive,” and “No Way To Stop It.” They’re the only two songs where Max and Elsa sing, they’re the only singers in each song. The significance of that is clear – Max and Elsa, with no romantic connection, share an outlook on life.

In “No Way To Stop It” that outlook is grim; the duet tries to persuade the Captain to go along with the inevitable Anschluss. They fail, and the Captan and Elsa agree to end their engagement.

But “How Can Love Survive,” earlier in the first act, is lighter and funnier and wittier, true R&H fare. Elsa knows that something is keeping the Captain from proposing, and Max suggests it’s because the couple, being wealthy, doesn’t face enough adversity. It’s a funny conceit, although also foreshadowing: how much money can you carry over the mountains on skis?

The numbers are important to the plot for two reasons – they make Max and Elsa into something more than cardboard characters, and serve in different degrees to show that Elsa isn’t the best match for the Captain, even in Maria’s absence. The show works better if Elsa’s somewhat likable; it makes the Captain’s emotional struggle more real.

The clip above is from the ITV’s live TV performance of the show from 2015, featuring Julian Ovenden as the Captain, probably better known to American audiences as Charles Blake on Downton Abbey and Andrew Foyle, the Inspector’s son, on Foyle’s War. He’s also a bona fide West End musical stage star.

Katherine Kelly is probably mostly unknown to Americans, but well-known to British viewers; they may not have known that she can sing like that. She may sing beautifully, but it’s her acting that really sells the song. The faux grim-visionary determination on the line, “two millionaires with a dream are we,” is hysterical.

Once I found the song, I looked through YouTube for some other stagings, and this one is the best by far. It’s suitably understated, and it only gains by including the Captain, where his presence for the song is often treated as optional. After you’re done, go back and watch it again, focusing on the servants. Chances are you barely noticed them the first time through.

Petty, Small Behavior, From Petty, Small-Minded People

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 4th, 2021

Over at the Washington Times, Brandon Weichert makes the case that the infant Biden Administration is taking deliberate and infantile aim at Elon Musk’s SpaceX and its efforts to colonize Mars in our lifetimes:

The FAA did not cite its reasoning behind ordering the cancellation of the launch. Many have speculated that the cancellation was brought about due to safety concerns. After all, in December 2020, SpaceX did a test of the experimental rocket. The Starship prototype made it to a height of 41,000 feet. Once it reoriented itself, in order to allow for the rocket to land vertically, the great silver spacecraft promptly did a bellyflop that ended in a massive explosion.

Despite this, SpaceX learned many valuable lessons from the December failure that were to be applied to the Starship launch in January. In science, the only lasting failure occurs when one does not test a new idea or hypothesis….

It’s likely that the FAA’s decision to cancel the launch is part of a wider Biden administration effort undo the Trump administration’s vibrant space policy. Plus, former President Trump’s space vision was explicitly aimed at countering advances made by China in space….

Concern over Mr. Musk’s Martian intentions is likely another factor for the FAA’s cancellation of the Starship launch. Last year, Mr. Musk indicated that any future SpaceX Martian colony would not be “ruled by Earth-based laws.” The problem for Mr. Musk is that SpaceX has been awarded lucrative contracts by the Earth-based U.S. government. If SpaceX were to create a colony on Mars, because of the company’s contractual relationship with the U.S. government, Washington very much expects that colony to be an American endeavor.

I’ve joked (mostly) before that the good news is that Elon Musk is the hero in an Ayn Rand novel, but that the bad news is that we’re living through an Ayn Rand novel. That just got a lot less funny, and a lot more enraging.

Weichert himself notes that the FAA’s possible safety concerns make no sense. NASA itself blew up dozens of rockets on launch or on the pad during the space race with the Soviets. Tragically, we also lost three astronauts during an Apollo test, nearly lost three more on Apollo 13, and only Neil Armstrong’s calm nerves and professionalism saved two more during the Gemini program.

And leave aside the national security and world-historic consequences of turning Mars and the high ground over to Chinese totalitarians, because I can’t think of a single reason why that shouldn’t carry the day all by itself.

There’s also a possibility that some of this is to protect Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin.

The most interesting point is Weichert’s last speculation, also easily the most short-sighted and petty, but typical of how our ideological elites think these days. Sure, it makes sense that Washington wants a Mars colony that’s loyal to the US, and it was probably unwise of Musk to shoot his mouth off about effective independence before he’s gotten there. But there are ways of satisfying everyone.

If DC were judicious and far-sighted, it would realize that as long as there’s a supply line reaching back to Earth, it will have the final say over much of what goes on in a Mars colony, but that at a practical level its direct control will be severely limited. Its best bet would be to do what the British Crown did with Massachusetts when it allowed the General Court to pass any laws that didn’t conflict with British law. Allow Mars to pass any laws that don’t conflict with the US Constitution.

More prosaically, though no less destructively, every “i” must be dotted, every “t” must be crossed before the program is allowed to proceed, which is why so little actually happens. Compare Israel’s Wuhan coronavirus vaccination program with New York’s. Israel set some basic guidelines, and then allowed flexibility in how they’d be implemented. Governor Cuomo threatened to start prosecuting people for giving vaccines “out of order.” Guess who’s vaccinated more of its people? Regardless of how all this shakes out, I’d rather be having this argument then, when there are actual colonists on the way, than now, when we’re still trying to figure out the engineering.

Musk’s dreams are grand, inspiring, breath-taking.

Too bad they’re being crushed by people who can’t stand actual hope.

The Economy Has No “Pause” Button (2)

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 3rd, 2021

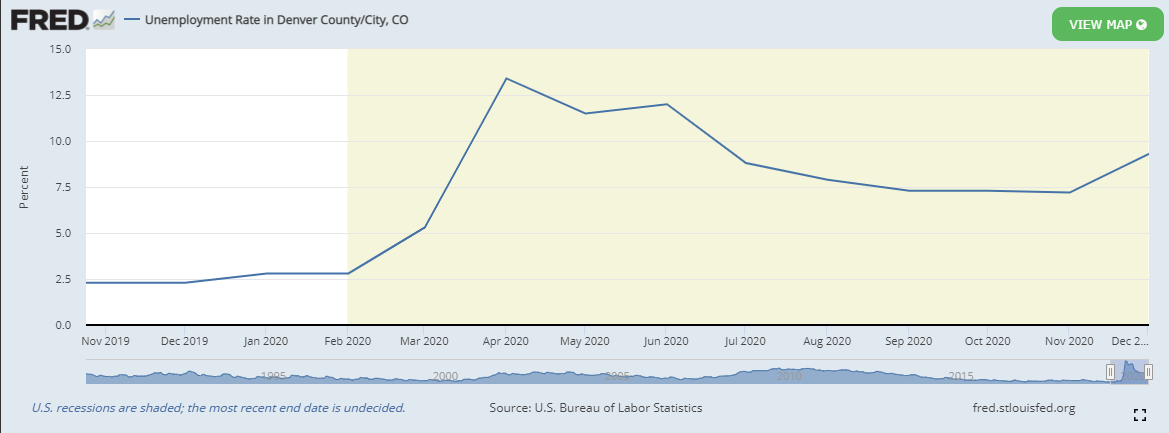

I’ve written over at Complete Colorado about how Colorado’s economy has been slow to recover from the government-induced recession in the wake of the Wuhan coronavirus.

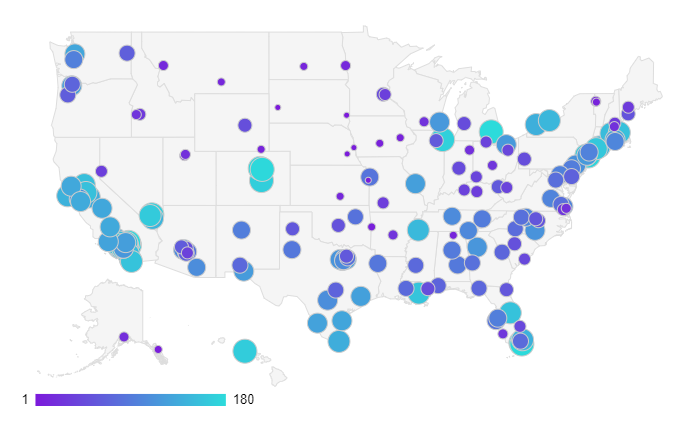

What’s true for Colorado is true for Denver, as well. In December of 2019, Denver’s unemployment rate was 2.5%, among the lowest in the country. Since then, it zoomed upward, recovered somewhat, and in the last months has gone up again, topping 10% if one includes those laid off.

According to a monthly survey by WalletHub, Denver’s increase in unemployment rate, at more than 300%, is 177th among the 180 cities they surveyed. Adjusted to include those laid off, it is at 10.14%, it is 155th on the list.

There is no question but that the city has had among the most aggressive restrictions in the state, attempting to regulate even out-of-city travel by residents. It was one of the first to implement a city-wide lockdown last March. It was slow to allow businesses to reopen. When the state announced its so-called 5-Star program, allowing restaurants in “red zones” qualify for increased seating, Denver was not near the front of the line for state approval.

Famously, Mayor Michael Hancock called for city residents to stay home for Thanksgiving, even as he was jetting off to Houston to visit his family in Mississippi for the holiday.

The mayor and much of the city council have been shameless cheerleaders for the state restrictions, preferring instead to grandstand about the Trump administration’s alleged failures with respect to the virus. And the result is not only devastating economically for Denver, but also for Aurora (#177) and Colorado Springs (#168). As is the case nationally, there is little evidence that all this ongoing economic pain has actually accomplished anything in the way of stopping the virus’s spread.