Archive for September, 2015

Podcast Experiment

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, Radio, Stacy Petty Show on September 30th, 2015

One of my fondest desires has been to produce a This American Life or RadioLab, only for free-market and conservative ideas. Thanks to Stacy Petty, I’ve actually been given a chance to do this.

One of my fondest desires has been to produce a This American Life or RadioLab, only for free-market and conservative ideas. Thanks to Stacy Petty, I’ve actually been given a chance to do this.

In one of his own podcast interviews, Dan Carlin of Hardcore History fame says that his goal has been to produce, for radio, a long-form edition of what a newspaper column would look like. That’s kind of what I’m aiming for here, as well. Edited, polished, but also using the illustrative and mood-setting background sound that radio give you, but newspapers don’t.

It’s unclear exactly what the format will be going forward, but here’s the first attempt, discussing PERA, the forthcoming State Auditor’s report on an early warning system, and small planes. It runs 10:30, but I’m hoping to bring future editions in at exactly 10:00.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

It’s Not Just Separation of Powers – It’s Also Federalism

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2016 Presidential Race, National Politics on September 25th, 2015

Facebook friend of mine Ken Gardner is fond of saying that a fair number of people who think they’re dissatisfied with Boehner and McConnell are really dissatisfied with the separation of powers. After all, any real change requires legislation, any legislation can be vetoed, and the Democrats in the Senate have proven that they won’t even let it come to that, with their abuse of the filibuster over the Iran deal.

Facebook friend of mine Ken Gardner is fond of saying that a fair number of people who think they’re dissatisfied with Boehner and McConnell are really dissatisfied with the separation of powers. After all, any real change requires legislation, any legislation can be vetoed, and the Democrats in the Senate have proven that they won’t even let it come to that, with their abuse of the filibuster over the Iran deal.

However, federalism plays as big a role as separation of powers. Our senators and representatives are from specific states and district, which can look very different from each other. In this respect, we are strikingly different from parliamentary democracies, even those such as Canada and the UK, where national slates really rule roost. In Will Mrs. Major Go to Hell?, William F. Buckley tells the story about a married couple, she from Massachusetts, he from Virginia. They discussed politics often, but never party registration. Turns out he was a Democrat, and she was a Republican, which came as a surprise to both of them. He being so conservative, she had assumed he was a Republican. She being so liberal, he had assumed she was a Democrat. Lots of fighting over that, apparently.

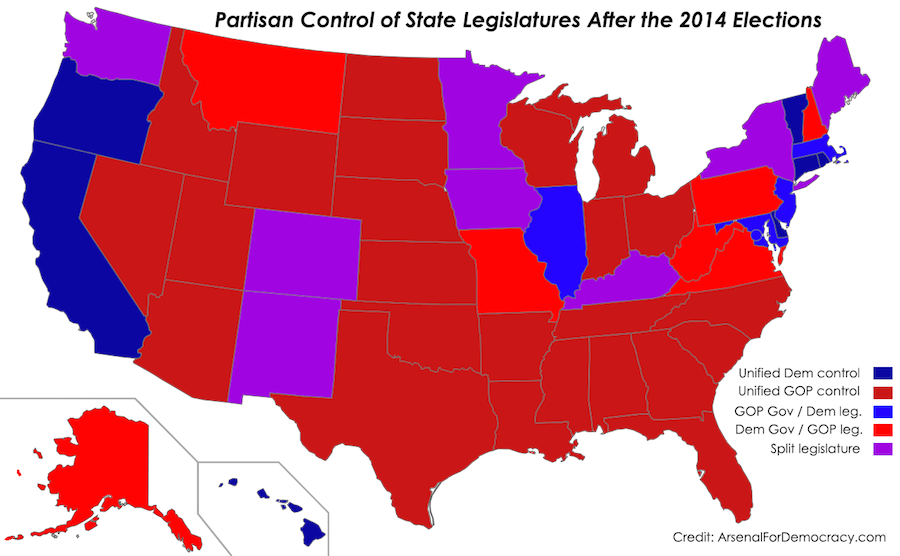

Those regional differences persist, even after the Great Reshuffling that began in earnest with the 1994 Congressional elections. The map that decorates this post, showing a broad swath of Republican legislative control across the country, masks a broad range of opinion and viewpoints. The Michigan and Wisconsin governments are run by Republicans, but I will promise you they are very different from Alabama and Mississippi.

That’s fine when you’re dealing with state issues. It comes into collision in Congress, where these regional Republicans have to sit in the same body.

When I was growing up, southern Congressional Democrats, who often voted conservatively, were referred to as “boll weevils,” while their northern liberal Republican counterparts were the “gypsy moths.” And it’s worth remembering that while Jesse Helms couldn’t have gotten elected in Minnesota, or Rudy Boschwitz in North Carolina, they both voted for the Reagan tax cuts.

What made it different was the “Reagan” part. Yes, the president has the veto power, but he also has the bully pulpit, and is the only office-holder elected by the entire country. He can set the agenda and give the party focus and direction in a way that it’s almost impossible for Congressional leaders to do.

There’s no question that Obama has broken the basic political agreement between citizens and the government:

Barack Obama has become the transformational president he aspired to be. Among the things he has transformed is the nature of the political compact between the rulers and the ruled in our republic.

Before Obama, citizens hoped that their elected leaders would be wise, independent, and disinterested leaders—but they never really counted on utopian vision. What they banked on was that the people they elected would, at the very least, be self-interested vote-seekers—so that if voters started punishing politicians for a specific course of action, the politicians would abandon it.

The passage of Obamacare broke this arrangement. And the impending passage of the Iran nuclear deal, in the face of voter discontent will cement this new relationship as the norm. In both cases, Democratic law makers went along in processes that were highly irregular (the nuclear option for passage of Obamacare; no treaty ratification with Iran); with initiatives they largely disliked on the merits; that voters demonstrably disliked in polling; and that had (or are likely to have) negative outcomes not just in the real world, but in the political world, too. This sort of power dynamic is new in American politics.

There’s also no question that Boehner and McConnell have been slow to recognize this shift, even as their opposite numbers on the Democrat side conspired in the reduction of Congress to an adjunct of the executive branch.

Whatever Boehner and McConnell may have “let” happen, real change will not come through Congressional action. It will have to wait for a Republican president, and even then, it will only happen with an energetic president committed to pushing legislation that devolves executive power back to Congress, reduces actual regulatory authority, and devolves federal power back to the states. It’s why primaries matter.

Obama is more Marius than Augustus, and we will not find our way back with a Sulla of our own. Sulla, of course, thought he was restoring the old order, but in the end, his lasting accomplishment was to establish a road map for future despots.

Politics and the Pope

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Jewish on September 24th, 2015

It w ould be unfair to say that this morning’s Papal speech to Congress has been the subject of immediate politicization, since that started even before the speech was given.

ould be unfair to say that this morning’s Papal speech to Congress has been the subject of immediate politicization, since that started even before the speech was given.

Lachlan Markay noted on Facebook how embarrassing it was to have pretty much everyone in Washington picking and choosing favored parts of the speech. Michael Walsh (alias David Kahane) implored non-Catholics to just shut up about the Pope, since he’s not an American politician.

Markay is right, that the attempt to claim the Pope for one’s own side is a trivializing exercise, mostly to the politicians involved. And Walsh is right that non-Catholics probably don’t understand Catholic doctrine very well.

That said, it’s pretty much an impossible situation for our political culture.

The Pope is a religious figure, which we tend to see as a non-political figure, who doesn’t fit neatly into American political categories. At the same time, he’s giving speeches where he opines on manifestly political topics, in an inherently political town, including one to an inherently political body. Not discussing these issues in a political context would be absurd. And indeed, why does the Pope speak on these subjects if not to influence the real world debate? Of course, that’s what he wants, and his means of doing do is to influence the moral framework through which Catholics see these issues.

To those who don’t like mixing politics and religion, though, the Papal visit a good reminder that almost all political arguments are inherently moral ones. Virtually every question in the public arena today is cast as a moral matter – from health care, to the environment, to welfare, to foreign policy, is a moral question. One of the reasons that conservatives tend to lose these debates is because we’re terrible at pointing out that our side has at least as good a moral argument as the allegedly caring Left. (It’s actually a far superior moral argument, but for purposes of this post, we’ll settle for there being two sides to the coin.)

That doesn’t mean the government has to get involved in everything, or that it should be a sectarian tool. But even libertarians make moral arguments about policy – they just claim that it’s more moral to leave the government out of most things. The case is a bit of a bank shot, but it’s got solid fundamentals – if capitalism raises people out of poverty, and if moral societies are more robust when mediating institutions are strong on their own, then a smaller government usually is more moral.

Where libertarians tend to lose out is when the judgment that the government shouldn’t be making moral calls leads them to complain about any moral judgments at all, and I’ve seen this happen – a lot. Both Thomas Merton and Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik would agree that no man is an island, that societies exist in the real world, and that they only work when they can internally enforce moral norms.

There is also some slight difference between starting from Catholic doctrine and arriving at political conclusions, and working backwards to find support for your politics in religious thought. The reporting on this Pope’s comments has been so truly awful that I really can’t tell how much of it is the press trying to co-opt the Pope for its lefty agenda, and how much really is organic. Much of the criticism of Pope Francis comes from people who assume he’s doing the latter.

It’s the same problem as when rabbis talk about politics from the pulpit, making the Reform rabbinate the marketing arm of the Democratic Party. Tradtional Judaism, which is to say, actual Jewish thought grounded in sources and Jewish law, is anything but socialist and redistributionist, anything but passive in the face of existential threats.

The fact that it, too, doesn’t fit neatly into contemporary party politics doesn’t meant that it doesn’t have something to say about contemporary controversies, or provide a framework that can inform the Jewish point of view on those subjects. It’s why the work being done by the Tikvah Fund, which works in the other, proper direction, is so admirable.

Who Do You Trust?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2016 Presidential Race, National Politics on September 17th, 2015

That was the name of a TV show back in the 50s & 60s, whose main claim to fame is launching the national career of a young star named Johnny Carson. Carson would go on to actually be a guy who people trusted enough to invite into their homes almost every night for 30 years.

was the name of a TV show back in the 50s & 60s, whose main claim to fame is launching the national career of a young star named Johnny Carson. Carson would go on to actually be a guy who people trusted enough to invite into their homes almost every night for 30 years.

It’s also the name of the game when electing a President, to a degree we often don’t like to admit to ourselves. We don’t govern the country by plebescite, and even if we did, a President would still be required to make a large number of major decisions for which he will only later be held accountable. Part of the reason we put so much emphasis on intangibles is that we need to be able to trust the man (or woman) making those decisions.

Some of this does come down to philosophy. There’s a principle in Jewish law that if you give someone a gold coin, but you tell them it’s a silver coin, they’re only responsible for taking care of it like a silver coin. Why? Because what’s important to you may not be important to them. If you want something treated like a gold coin, you need to make sure that the person you’re giving it to values it that way. It’s the reason that we demand that kosher supervisors keep kosher themselves.

In the same way, people who are passionate about a particular issue will want proof that a candidate is as sincerely intense (or intensely sincere) about it as they are. If you really care about guns, then a comment like Ben Carson’s about not needing semi-automatics in a big city is a disqualifier.

If you really care about small government, then you want someone you can trust to be making the small decisions that reduce the power of the executive, and who’ll take on entitlement reform. You want someone who invests his staff, from the cabinet on down, with that same zeal, and who is always guiding the budget, rule-making, and legislative processes in that direction. You can’t measure that on a day-to-day basis. You have a business to run, a job to do. You need to trust that it matter to him (or her), and that what you don’t see is also going in the right direction.

It’s the main reason that – for President – I prefer governors to senators, and politicians to newbies. What do they care enough about to keep, and what do they consider to be disposable? Governors have to make decisions and run organizations, while senators have to run their mouths and cast votes. Newbies may have opinions, serious opinion even, but they haven’t been tested in the crucible of tradeoffs and compromise that our system is built on.

And as difficult as things in Austin or Madison or Tallahassee or Columbus might be, they’re nothing like DC. If you want real change – not just a return to normalcy that ratifies the wreckage of the last 8 years, but a real effort, against colossal pressures, to undo the damage wrought by this administration in virtually every area of our public life, then you need to trust that that person will be disciplined and energetic, as well as persuasive.

That sort of trust, as well as the 3 AM Phone Call-kind of trust, needs to be projected. And as a voter, it requires judgment about character, discipline, and energy, as well as political philosophy and how deeply they’ve thought about the issues at hand.

Here’s what I think I know about the candidates so far. The one guy I could trust on all counts just dropped out. So much for Perry. Trump has shown me that I can’t trust him. Rubio and Fiorina have earned the right to convince me. Fourteen months away from the election, six months away from our state caucus, that’s about all I’ll commit to for them. I remain wary of Cruz, who I think would make a dynamite Supreme Court Justice, but who politically, seems to always have more of an angle than a plan. Paul has shown me that I can trust him on foreign policy – to pretty much always be wrong. Walker has pretty much shaken my trust in his instincts, at least in primaries, and will need to work to get it back. Carson, I’d love to have over for a meal – I could trust him with my best china and most delicate stemware, as well as to provide entertaining, charming conversation. And Kasich and Bush, I think I could trust to be solid men who wouldn’t do a lick to roll back Obamacare or reimpose sanctions on Iran.

One last word about Fiorina, since she’s the one non-professional I’m considering. The reason she’s earned to right to persuade me is that she says most of the right things, is quick on her feet, but also projects being in control. She also knows how to use her gender to advantage without beating you over the head with it, which I think is part of the reason she’d do well in the general – women don’t like Hillary; women do like Carly. That said, there’s danger there that she becomes the Republican gender-based version of the Democratic race-based Barack Obama: we get so swept up in the idea of electing a woman that we forget that we’re electing a real person we need to trust to make the right decisions. We need to be sure of what we’re getting, and not let smoke get in our eyes.

Of course, people can also vote against not trusting someone. I know people who bit their fingernails before voting for Nixon in 1972, hoping they did the right thing, and who did the same thing in 1976 with someone who made trust an explicit campaign theme, which would indicate some insecurity on the subject. Many uneasily trusted Ronald Reagan in 1980, when the incumbent asked openly if we could “trust” him with his finger on the button. By 1992, many had decided they couldn’t trust George H.W. Bush, and by 1996, decided they could trust Clinton politically, if not personally. In 2012, Obama had lost the trust of many American Jews, and by 2015, I personally can’t see how he’s retained the trust of any. (Whether or not that creates an electoral opportunity for the 2016 Republican nominee is also a matter of trust, something last night’s Ann Coulter tweets did nothing to help.)

Of course, people can also vote against not trusting someone. I know people who bit their fingernails before voting for Nixon in 1972, hoping they did the right thing, and who did the same thing in 1976 with someone who made trust an explicit campaign theme, which would indicate some insecurity on the subject. Many uneasily trusted Ronald Reagan in 1980, when the incumbent asked openly if we could “trust” him with his finger on the button. By 1992, many had decided they couldn’t trust George H.W. Bush, and by 1996, decided they could trust Clinton politically, if not personally. In 2012, Obama had lost the trust of many American Jews, and by 2015, I personally can’t see how he’s retained the trust of any. (Whether or not that creates an electoral opportunity for the 2016 Republican nominee is also a matter of trust, something last night’s Ann Coulter tweets did nothing to help.)

In the end, trust is part of the reason that people get very testy when you criticize their chosen candidate: you’re not just discussing a person, you’re criticizing their own judgment, as well, and a personal bond the candidate has forged with them. Which is why it shouldn’t be easily earned or easily given.