Archive for August, 2016

The Temper of Our Time – III

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 31st, 2016

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

Hoffer identifies the essential tragedy of the black American:

This country has always seemed good to me chiefly because, most of the time, I can be a human being first and only secondly something else – a workingman, an American, etc. It is not so with the Negro. His chief plight is that in America, he cannot be first of all a human being. This is particularly galling to the Negro intellectual and to Negroes who have gotten ahead: no matter what and how much they have, they seem to lack the one thing they want most. There is no frustration greater than this.

Much has changed in the last 50 years in race relations, some for the good, some for the worse. But when you hear someone say, “Nothing’s changed,” I suspect that it is this, more than anything else, that he means. I think this is still largely true. Black Americans are stuck with a collective identity, whether they want it or not. Leftism has decided that p identity is indelible for all of us, that this a good thing, and that it should be reinforced by government regulation and bureaucracy from the time we are children. In doing so, it’s risked fracturing the country by undermining its basis, but it’s also made things much, much worse for blacks.

How?

The Negroes who emigrate from the South cannot repeat the experience of the millions of European immigrants who came to this country. The European immigrants not only had an almost virgin continent at their disposal and unlimited opportunities for individual advancement, but were automatically processed on their arrival into new men: they had to learn a new language and adopt a new mode of dress, a new diet, and often a new name. The Negro immigrants find only meager opportunities for self-advancement and do not undergo the “exodus experience,” which would strip them of traditions and habits and give them the feeling of being born anew. Above all, the fact that in America, and perhaps in any white environment, the Negro remains a Negro first, no matter what he becomes or achieves, puts the attainment of a new individual identity beyond his reach.

By depriving the black man of the opportunity to create his own new identity, because he’s never been forced to shed the old one. And for some decades now, the rest of us are being encouraged to undo the salutary effects of immigration. (What this says about new immigrants to the US should be pretty obvious. But even then, it’s worth noting that black immigrant from Africa and the Caribbean do about as well as immigrants from other countries, because they’ve had to undergo the immigrant experience.)

In this regard, blacks were doubly victimized by trendy leftism. Black civil rights successes came round about the same time as African countries were winning independence from Europe. Hoffer points out that just as Jewish success in Israel had bolstered the self-confidence of Jews worldwide, blacks in the US should have been a model for Africans. Instead, US blacks were misguidedly encouraged to look to dictators and ideologues like Nkruma for inspiration, setting back their own development at a critical moment of development. Black leaders in the US spent the better part of two decades trying to transplant African nationalist movements into very unhospitable soil.. Thanks for nothing.

Hoffer’s suggestion is one that remains as true today as it was half a century ago:

What can the American Negro do to heal his soul and clothe himself with a desirable identity? It has to be a do-it-yourself job….Non-Negro America can offer only money and goodwill….

The only road left for the Negro is community building. Whether he wills it or not, the Negro in America belongs to a distinct group, yet he is without the values and satisfactions which people usually obtain by joining a group. When we become members of a group, we acquire a desirable identity, and derive a sense of worth and usefulness by sharing in the efforts and achievements of the group. Clearly, it is the Negro’s chief task to convert this formless and purposeless group to which he is irrevocably bound into a genuine community capable of effort and achievement and which can inspire its members with pride and hope.

Whereas the American mental climate is not favorable for the emergence of mass movements, it is ideal for the building of viable communities; and the capacity for community building is widely diffused.

Hoffer makes it clear he’s not talking about the ghetto, but about broader black community institutions, and the re-engagement of the black middle class with the masses. And it doesn’t mean a separate, segregated, parallel society, but black institutions capable of creating a sense of community for people participating in the larger American society. All that talk about deriving a sense of worth isn’t statism or “collectivism” in a destructive sense (although it obvious has the potential for misuse). This is a real part of how people operate in the real world that libertarians ignore or ridicule at their own peril – communities matter to people, even if our legal rights come to use solely by virtue of our individuality.

And here’s the second great betrayal off blacks by the Left. Just as blacks were gaining the chance to remake their own communities with far fewer legal obstructions, the federal government swooped into destroy those institutions by replacing the black father with a welfare check. We’ve seen the results – absent fathers lead to unmanageable boys and now, generations of crime, a downward spiral that make community-building that much harder.

So along with the virtual elimination of legal barriers, the social barriers seem only to have gotten higher. That much, at least, has changed.

The Temper of Our Time – II

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 30th, 2016

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

The simple fact is that the people I have lived and worked with all my life, who make up about 60 percent of the population outside the South, have not the least feeling of guilt toward the Negro. The majority of us started to work for a living in our teens, and we have been poor all our lives. Most of us had only a rudimentary education. Our white skin brought us no privileges and no favors. For more that twenty years I worked in the fields of California with Negroes, and now and then for Negro contractors. On the San Francisco waterfront, while I spent the next twenty years, there are as many black longshoremen as white. My kind of people does not feel that the world owes us anything, or that we owe anybody – white, black, or yellow – a damn thing. We believe that the Negro should have every right we have: the right to vote, the right to join any union open to us, the right to live, work, study, and play anywhere he pleases. But he can have no special claims on us, and no valid grievances against us. He has certainly not done our work for us. Our hands are more gnarled and workbroken than his, and our faces more lined and worn. A hundred Baldwins could not convince me that the Negro longshoremen who come every morning to our hiring hall shouting, joshing, eating, and drinking are haunted by bad dreams and memories of miserable childhoods, that they feel deprived, disabled, degraded, oppressed, and humiliated. The drawn faces in the hall, the brooding backs, and the sullen, hunched figures are not those of Negroes.

The South has a special burden to bear (although to what extent it still does is another question), but for most of white America outside the South, I think this fairly sums up the attitude, if not universally the work experience. And I think it’s about right. People should be able to pursue their life’s path without laboring under legal handicaps because of their race. I have no doubt that it accurately reflects Hoffer’s own inclinations, and that of his brother dockworkers in mid-1960s San Francisco. They worked hard, and didn’t create or perpetuate the hardships that blacks had suffered.

But if Hoffer understands that the black man’s tragedy is that he can’t be an individual without being seen as black first, he seems to miss who’s doing the seeing. Hoffer’s a union guy through and through, but the union movement in the North gained great strength in response to the influx of black workers during the Great Migration, especially during the Depression, and worked hard to deny blacks the benefits of union membership. Hoffer doesn’t have to answer for that behavior, but he should have at least acknowledged that it existed, and the effects it had on blacks outside the South.

The more relevant question is what it does for blacks. Hoffer’s main point, which I’ll examine in greater length in another post, was the what blacks needed wasn’t cheap, easy, flashy political victories, but community institutions that would give him pride, security, and and self-respect.

The Temper of Our Time

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 28th, 2016

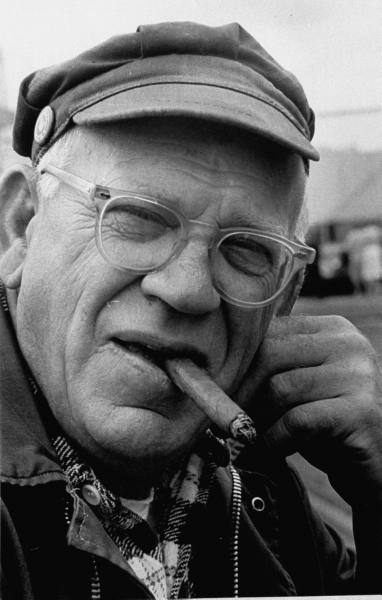

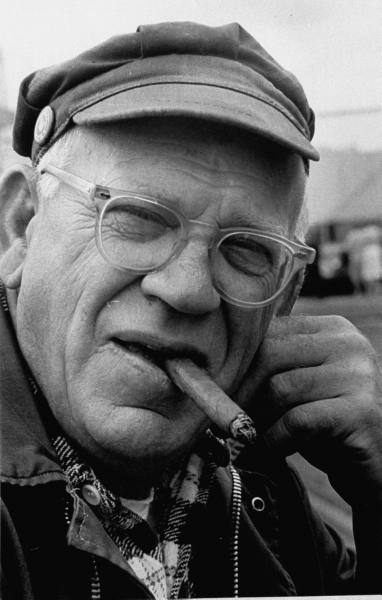

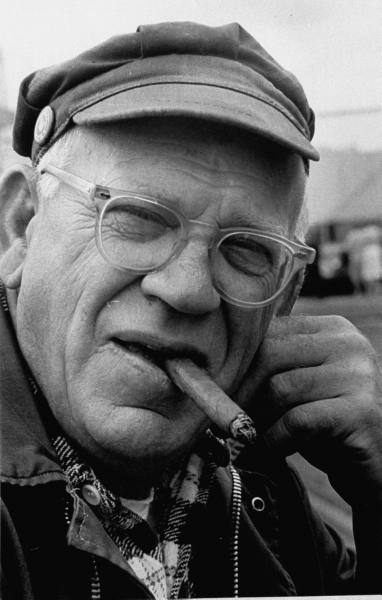

Eric Hoffer was known as the “Longshoreman Philosopher,” mostly because that’s what he was. Born in the Bronx in 1902, he lived most of his life as a migrant worker and then a longshoreman. He had spent 50 years reading, observing, and thinking before producing his first and best-known book, The True Believer, about the psychology of mass movements.

Eric Hoffer was known as the “Longshoreman Philosopher,” mostly because that’s what he was. Born in the Bronx in 1902, he lived most of his life as a migrant worker and then a longshoreman. He had spent 50 years reading, observing, and thinking before producing his first and best-known book, The True Believer, about the psychology of mass movements.

Hoffer’s writing is blunt, direct, thoroughly working-class and thoroughly American, but neither his style nor his ideas are simple. Unlike academicians who do field work in red states, he’s not writing to explain the working man to the rest of the country; he’s writing as a working man talking to the rest of the country.

By 1967, he had written several more books including The Temper of Our Time, which he characterized as impatient, and he provides a number of examples. The book is short – six essays, about 110 pages in all. When his publisher complained about the length, he replied that it had six original ideas and twelve excellent sentences. If he had bought a book of any length that had six original ideas and twelve excellent sentences, he would have felt that he had gotten a good deal.

I think Hoffer sold himself short. I found many more than six original ideas, and many more than twelve superb sentences. I don’t propose to go over all of them here, but let’s start with a story:

When we speak of the American as a skilled person, we have in mind not only technical but also his political and social skills. Once, during the Great Depression, a construction company that had to build a road in the San Bernadino Mountains sent down two trucks to the Los Angeles skid row, and anyone who could climb onto the trucks was hired. When the trucks were full, the drivers put in the tailgates and drove off. They dumped us on the side of a hill in the San Bernadino Mountains, where we found bundles of supplies and equipment. The company had only one man on the spot. We began to sort ourselves out: there were so many carpenters, electricians, mechanics, cooks, men who could handle bulldozers and jackhammers, and even foremen. We put up the tents and the cook shack, fixed latrines and a shower bath, cooked supper and next morning went out to build the road. If we had to write a constitution we probably would have had someone who knew all the whereases and wherefores. We were a shovelful of slime scooped off the pavement of skid row, yet we could have built America on the side of a hill in the San Bernadino Mountains.

And so the paradox of America in Hoffer’s day was – how is it that a country that produces so little leadership in normal times manages to produce great leaders when it needs them?

Hoffer doesn’t directly answer the question, but I think the answer lies in the very capacity for self-organization. People who are capable of self-organization don’t need external leadership to tell them what to do in normal times. What defines abnormal times is the nature of the large-scale projects to be accomplished – winning a war, for instance. But the American’s capacity for self-organization makes the leader’s job easier in those circumstances. Leadership is free to focus on the general direction things need to take, and leave the lower-level problem-solving to the lower levels.

Hoffer’s quote comes in the context of the American genius for community-building. One of the most destructive aspects of leftism has been the shrinking of our citizens’ initiative when it comes to communities, where more and more basic functions are left to city government, and individual or neighborhood initiative often needs to wait for government approval. Even the petty bureaucrats of HOAs enjoy pseudo-governmental authority.

Americans’ ability to spontaneously and collectively solve problems on their own does survive, though, both in the military and in private business. Every successful business I’ve worked in encourages small groups to solve technical problems, and every unsuccessful one has been a top-down affair. When I got my MBA 11 years ago, the management classes were definitely the most trendy social-sciency courses, but they all stressed leadership in terms of empowering employees rather than directing them. That strikes me as a very American approach, where workers generally think of themselves as equal to their bosses.

Presidential Candidates’ Health Then And Now

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 22nd, 2016

Hillary Clinton is not a young woman. If elected President, Mrs. Clinton would be a few months younger than Ronald Reagan was when he was first elected. Mrs. Clinton also suffered a fall and a concussion in 2012. The cause of the fall has not been determined, and the extent of the concussion has been the subject of some informed speculation.

Hillary Clinton is not a young woman. If elected President, Mrs. Clinton would be a few months younger than Ronald Reagan was when he was first elected. Mrs. Clinton also suffered a fall and a concussion in 2012. The cause of the fall has not been determined, and the extent of the concussion has been the subject of some informed speculation.

Much of this was covered by the press in 2014, but there have been no definitive answers from the Clinton camp, and as usual, the press has responded with its usual lack of curiosity where Democrats are concerned, and has been content with being stiffed by the campaign.

It has therefore fallen to the Trump campaign to raise the issue, in its usual ham-handed way. The press has responded by, more or less, suggesting that there is something inappropriate in raising the question of a candidate’s health.

And yet, I can recall plenty of speculation about Reagan’s mental capacity in 1980. Mark Russell even did a song about Reagan promising to quit if he became senile while in office.

Another candidate who faced a lot of discussion about his health was John McCain in 2008. A few minutes of googling produced the following:

- On the Campaign Trail, Few Mentions of McCain’s Bout With Melanoma – New York Times

- McCain’s Age and Past Health Problems Could Be An Issue in the Presidential Race – U.S. News

- How Healthy is John McCain? – Time

- McCain’s Health Records – New York Times

- John McCain’s Health – CNN

- McCain Healthy But Cholesterol Concerns Remain – ABC News

- What’s In John McCain’s Medical Records? – Salon

- Liberal PACs Ready Attack Ad on McCain’s Health – New York Times

- McCain Faces Questions on Age, Health – CNN

Indeed, the NY Times post about the attack ad evidences an acknowledgement that some people might be mildly uncomfortable with such an ad, but mostly simply reports on the ads content, and concerns about illegal coordination with the Obama campaign or the Democratic Party.

Uninformed or wild speculation about Clinton’s health is, of course, irresponsible. But merely raising the question?

This seems to be another example of a special “Hillary Rule.”