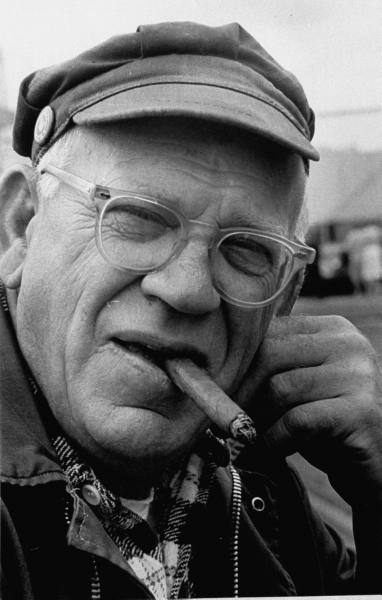

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

The simple fact is that the people I have lived and worked with all my life, who make up about 60 percent of the population outside the South, have not the least feeling of guilt toward the Negro. The majority of us started to work for a living in our teens, and we have been poor all our lives. Most of us had only a rudimentary education. Our white skin brought us no privileges and no favors. For more that twenty years I worked in the fields of California with Negroes, and now and then for Negro contractors. On the San Francisco waterfront, while I spent the next twenty years, there are as many black longshoremen as white. My kind of people does not feel that the world owes us anything, or that we owe anybody – white, black, or yellow – a damn thing. We believe that the Negro should have every right we have: the right to vote, the right to join any union open to us, the right to live, work, study, and play anywhere he pleases. But he can have no special claims on us, and no valid grievances against us. He has certainly not done our work for us. Our hands are more gnarled and workbroken than his, and our faces more lined and worn. A hundred Baldwins could not convince me that the Negro longshoremen who come every morning to our hiring hall shouting, joshing, eating, and drinking are haunted by bad dreams and memories of miserable childhoods, that they feel deprived, disabled, degraded, oppressed, and humiliated. The drawn faces in the hall, the brooding backs, and the sullen, hunched figures are not those of Negroes.

The South has a special burden to bear (although to what extent it still does is another question), but for most of white America outside the South, I think this fairly sums up the attitude, if not universally the work experience. And I think it’s about right. People should be able to pursue their life’s path without laboring under legal handicaps because of their race. I have no doubt that it accurately reflects Hoffer’s own inclinations, and that of his brother dockworkers in mid-1960s San Francisco. They worked hard, and didn’t create or perpetuate the hardships that blacks had suffered.

But if Hoffer understands that the black man’s tragedy is that he can’t be an individual without being seen as black first, he seems to miss who’s doing the seeing. Hoffer’s a union guy through and through, but the union movement in the North gained great strength in response to the influx of black workers during the Great Migration, especially during the Depression, and worked hard to deny blacks the benefits of union membership. Hoffer doesn’t have to answer for that behavior, but he should have at least acknowledged that it existed, and the effects it had on blacks outside the South.

The more relevant question is what it does for blacks. Hoffer’s main point, which I’ll examine in greater length in another post, was the what blacks needed wasn’t cheap, easy, flashy political victories, but community institutions that would give him pride, security, and and self-respect.