Archive for August 31st, 2016

The Temper of Our Time – III

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 31st, 2016

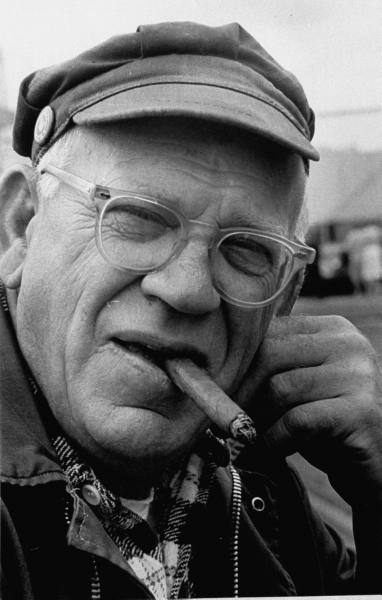

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

Hoffer identifies the essential tragedy of the black American:

This country has always seemed good to me chiefly because, most of the time, I can be a human being first and only secondly something else – a workingman, an American, etc. It is not so with the Negro. His chief plight is that in America, he cannot be first of all a human being. This is particularly galling to the Negro intellectual and to Negroes who have gotten ahead: no matter what and how much they have, they seem to lack the one thing they want most. There is no frustration greater than this.

Much has changed in the last 50 years in race relations, some for the good, some for the worse. But when you hear someone say, “Nothing’s changed,” I suspect that it is this, more than anything else, that he means. I think this is still largely true. Black Americans are stuck with a collective identity, whether they want it or not. Leftism has decided that p identity is indelible for all of us, that this a good thing, and that it should be reinforced by government regulation and bureaucracy from the time we are children. In doing so, it’s risked fracturing the country by undermining its basis, but it’s also made things much, much worse for blacks.

How?

The Negroes who emigrate from the South cannot repeat the experience of the millions of European immigrants who came to this country. The European immigrants not only had an almost virgin continent at their disposal and unlimited opportunities for individual advancement, but were automatically processed on their arrival into new men: they had to learn a new language and adopt a new mode of dress, a new diet, and often a new name. The Negro immigrants find only meager opportunities for self-advancement and do not undergo the “exodus experience,” which would strip them of traditions and habits and give them the feeling of being born anew. Above all, the fact that in America, and perhaps in any white environment, the Negro remains a Negro first, no matter what he becomes or achieves, puts the attainment of a new individual identity beyond his reach.

By depriving the black man of the opportunity to create his own new identity, because he’s never been forced to shed the old one. And for some decades now, the rest of us are being encouraged to undo the salutary effects of immigration. (What this says about new immigrants to the US should be pretty obvious. But even then, it’s worth noting that black immigrant from Africa and the Caribbean do about as well as immigrants from other countries, because they’ve had to undergo the immigrant experience.)

In this regard, blacks were doubly victimized by trendy leftism. Black civil rights successes came round about the same time as African countries were winning independence from Europe. Hoffer points out that just as Jewish success in Israel had bolstered the self-confidence of Jews worldwide, blacks in the US should have been a model for Africans. Instead, US blacks were misguidedly encouraged to look to dictators and ideologues like Nkruma for inspiration, setting back their own development at a critical moment of development. Black leaders in the US spent the better part of two decades trying to transplant African nationalist movements into very unhospitable soil.. Thanks for nothing.

Hoffer’s suggestion is one that remains as true today as it was half a century ago:

What can the American Negro do to heal his soul and clothe himself with a desirable identity? It has to be a do-it-yourself job….Non-Negro America can offer only money and goodwill….

The only road left for the Negro is community building. Whether he wills it or not, the Negro in America belongs to a distinct group, yet he is without the values and satisfactions which people usually obtain by joining a group. When we become members of a group, we acquire a desirable identity, and derive a sense of worth and usefulness by sharing in the efforts and achievements of the group. Clearly, it is the Negro’s chief task to convert this formless and purposeless group to which he is irrevocably bound into a genuine community capable of effort and achievement and which can inspire its members with pride and hope.

Whereas the American mental climate is not favorable for the emergence of mass movements, it is ideal for the building of viable communities; and the capacity for community building is widely diffused.

Hoffer makes it clear he’s not talking about the ghetto, but about broader black community institutions, and the re-engagement of the black middle class with the masses. And it doesn’t mean a separate, segregated, parallel society, but black institutions capable of creating a sense of community for people participating in the larger American society. All that talk about deriving a sense of worth isn’t statism or “collectivism” in a destructive sense (although it obvious has the potential for misuse). This is a real part of how people operate in the real world that libertarians ignore or ridicule at their own peril – communities matter to people, even if our legal rights come to use solely by virtue of our individuality.

And here’s the second great betrayal off blacks by the Left. Just as blacks were gaining the chance to remake their own communities with far fewer legal obstructions, the federal government swooped into destroy those institutions by replacing the black father with a welfare check. We’ve seen the results – absent fathers lead to unmanageable boys and now, generations of crime, a downward spiral that make community-building that much harder.

So along with the virtual elimination of legal barriers, the social barriers seem only to have gotten higher. That much, at least, has changed.