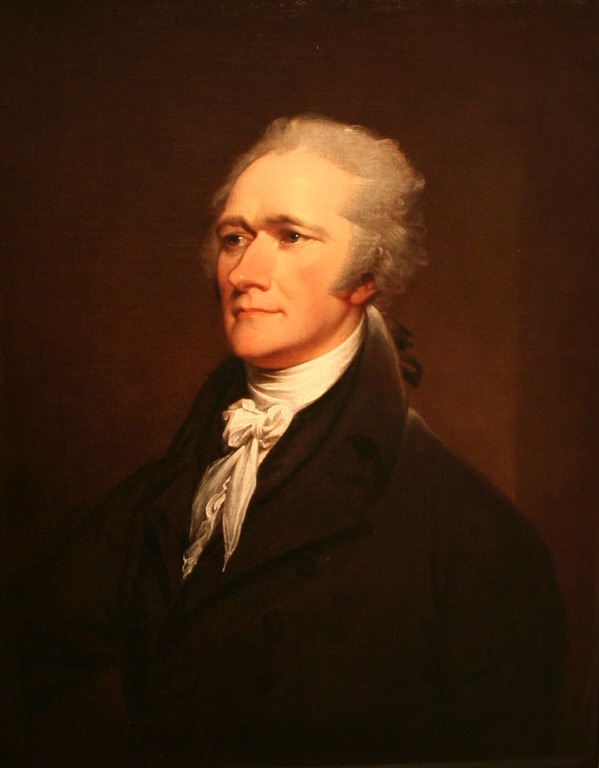

I may be the last person on the planet to have read Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. I’ll certainly be digesting it for a while.

Among Chernow’s contributions is a detailed discussion of the American political climate, during the Washington and Adams administrations, when the bulk of Hamilton’s contributions to the nascent government were made. It’s also when we saw the emergence of the first real political parties in history, parties committed to more than the mere attaining and retaining of power, but also to rival economic and political theories.

Today, we’re used to the stability of the two-party system, but at the time, they were not only a novelty, but a bit of a shameful one at that. The Founders had wanted to avoid factions, or parties. The new parties were not only organized around ideas, but also around the personalities of their leaders. This led to a curious combination of personal touchiness, mutual misunderstanding and hostility, and denial that it was going on at all.

From Pages 391-92 of the softcover edition:

The sudden emergence of parties set a slashing tone for politics in the 1790s. Since politicians considered parties bad, they denied involvement in them, bristled at charges that they harbored partisan feelings, and were quick to perceive hypocrisy in others. And because parties were frightening new phenomena, they could be easily mistaken for evil conspiracies, lending a paranoid tinge to political discourse. The Federalists saw themselves as saving America from anarchy, while Republicans believed they were rescuing America from counterrevolution. Each side possessed a lurid, distorted view of the other, buttressed by an idealized sense of itself. No etiquette yet defined civilized behavior between the parties. It was also not evident that the two parties would smoothly alternate in power, raising the unsettling prospect that one party might be established to the permanent exclusion of the other. Finally, no sense yet existed of a loyal opposition to the government in power. As the party spirit grew more acrimonious, Hamilton and Washington regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature.

One last feature of the inchoate party system deserves mention. The emerging parties were not yet fixed political groups, able to exert discipline on errant members. Only loosely united by ideology and sectional loyalties, they can seem to modern eyes more like amorphous personality cults. It was as if the parties were projections of individual politicians – Washington, Hamilton, and then John Adams on the Federalist side, Jefferson, Madison, and then James Monroe on the Republican side – rather than the reverse. As a result, the reputations of the principle figures formed decisive elements in political combat. For a man like Hamilton, so watchful of his reputation, the rise of parties was to make him ever more hypersensitive about his personal honor.

The parallels between the politics of that day, when parties were being formed, and today, when they have been structurally weakened and are in flux, should be obvious. The party establishments and the administrative state mitigate some of the effects, but there’s no question that election laws have neutered party back-rooms and allowed anyone to run under a party banner. The move towards open primaries further erodes party discipline. Each party increasingly sees the other less as principled opposition and more as a conspiracy bordering on organized crime. And there is no question that the Bush and Clinton dynasties, along with the personally prickly Obama and Trump, have personalized presidential politics to a degree we’ve not seen in a while.

Over the last several presidential elections, people have called attention to the vitriolic nature of political campaign rhetoric, if not (until 2016) by the candidates themselves, then by their surrogates and supporters. As often, people have trotted out some of the truly vicious things said in the campaign of 1800. With a somewhat broader view, that similarity seems less a coincidence and more like the product of a common cause.