Posts Tagged Trains

Staggering Improvement

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, Regulation, Transportation on October 27th, 2014

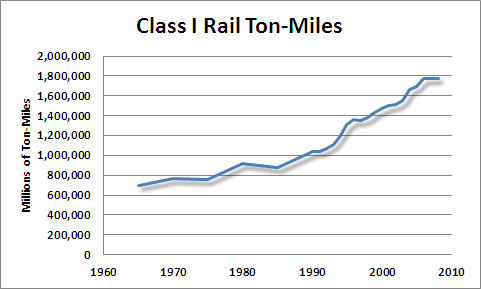

Looking over a CoBank report on the state of rail capacity in the West, I came across this astonishing graph:

The Staggers Act effectively deregulated the rail industry in this country, after almost a century of increasingly heavy-handed rules set out by the Interstate Commerce Commission (RIP). It took a few years for volume to rise, but contrary to the arguments of the regulators, rates fell, revenue fell, and productivity shot up almost overnight. As effects rippled through the economy, volume began to take off.

In recent years, as the cost of fuel has risen, and capacity constraints have become more evident, rates and revenue have started to rise, which accounts for the turnaround in railroad stocks.

What’s really striking is the stasis that the railroad industry was held in before 1980. The ICC set their rates, limited their service, and forced freight lines to continue to run unprofitable and largely unused passenger service, competing with bus lines that were getting significant federal help through the interstate highway system. How much of the overall economy’s stagnation and deterioration through the 60s and 70s was a result of this misguided paternalism can only be guessed at.

Harley Staggers, the author and chief sponsor of the Staggers Act, was no economic or political libertarian. He was a 16-term Democratic representative from West Virginia who tried to subpoena the footage from a CBS documentary on Watergate and filed an FCC complaint over the F-word in a song on a radio station. But he had enough sense to see that Appalachia’s coal industry needed a healthy railroad system to grow. He’s lucky that this act from his final term in office is what people remember him by.

In For The Long Haul

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, PPC, Transportation on June 6th, 2011

Well, this is interesting. From Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s AAR reports from the last two years:

Coal, as you can see, makes up about half of car loadings, and that’s headed down. Just from the couple of years, it looks as though there may be some seasonality in Intermodal, falling off in the last quarter. I’ll know some more when I look at Union Pacific (back to 2002 and also mostly western) and CSX (back to 2006, but mostly the northeast and south). Intermodal has improved through this year, but coal has been dropping for about 6 months.

Since the beginning of the year, coal has decoupled – so to speak – from the rest of loadings, which have climbed slightly or stayed level, even as coal has dropped. We export a great deal of coal, and BNSF serves the western half of the country, Mexico, Canada, and the Gulf of Mexico. (The railyard north of downtown Denver is a BNSF railyard, although we have a fair number of UP lines through the state, too.) There have been reports that China’s been slowing down, and nobody really trusts – or should trust – the official numbers coming out of there. Is it possible that fewer coal loadings as a sign of slackening Chinese demand?

I’m not quite sure what to make of the stagnating carloads combined with the improving outlook for intermodal. We know that, over long distances, trains are more efficient than trucks. Intermodal will continue to grow as a percentage of both rail traffic and overall freight ton-miles. Is it possible that this is just more inefficiency being wrung out of the system? Any other ideas?

A Tale of Two Trains

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on May 18th, 2011

Funny thing about trains. They work well for people over short distances when the densities are high enough, but are terrible over long, wide-open spaces. They work well for freight over long distances, but lose those efficiencies over short distances.

In the first instance, Amtrak, with record ridership, is losing more money than ever. The northeast corridor is making money, but the long-haul trains through the sparsely populated Not Northeast gives it all back, and more. Amtrak’s argument for keeping routes like the California Zephyr is that they provide a service to people who have no other means of transportation. It’s exactly the same argument that led the ICC to require the Western Pacific to keep running this line even though they were hemmorhaging money.

How many people? Well, let’s take the segment that I often use, the part between Denver and Omaha. Now, people in Lincoln can drive to the Omaha airport. If we add up all the alightings and boardings between Lincoln and Denver for 2010, not including Lincoln and Denver, we get 13,295 people. That’s 13,295 people boarding and leaving the train at those four stations, for the whole year. About 36 people a day. Part of this is the time of night, but why do you think this part of the trip is overnight?

I love taking the train rather than flying. I like that it’s overnight, that it’s less hurried, that I can get up a little early or stay up a little late and work, and that I don’t have to subject myself to a cavity exam. But let’s not pretend this is an economical way to travel out here.

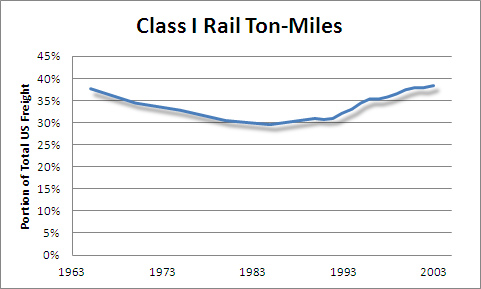

Freight is another matter. Ever since the ICC went away, rail freight as a percentage of total freight has been rising. In part, that’s because the lines have been able to invest a little in their operations, rather than being told that any profit is too much and being treated like utilities. And in the last year, intermodal traffic – a combination of rail and truck – grew 9% year-over-year, even as total rail traffic increased only 0.5%.

Steven Hayward has an interesting post about rail efficiency, and the fuel efficiency of engines:

In fact, the energy intensity of locomotives has improved substantially, with BTUs per freight mile falling by 65 percent since 1960. In other words, although total freight-rail miles have tripled since 1960, total railroad fuel consumption has remained about flat. If railroad locomotives had made no efficiency improvements since 1960, we’d have needed 9.2 billion gallons of fuel in 2009 instead of the 3.1 billion gallons actually consumed.

Passenger trains may have cafe cars, but freight trains have no CAFE standards of which I am aware.

Atlas Shrugged and the Railroads

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on April 22nd, 2011

Interestingly, one of the complaints that conservatives have about Atlas Shrugged is that the movie centers around a railroad. (McClatchy, too, but then, they’ll believe – or not – pretty much anything.) For some reason, they have a hard time believing that people will, or do, actually use railroads.

In fact, rail is increasingly important for freight, and has been on the upswing for a couple of decades now. Take a look at these following charts derived from Bureau of Transportation Statistics data. Overall Class I (major trunk line) ton-mileage stalled in the 70s, but started upward again with deregulation and the welcome death of the Interstate Commerce Commission:

And as a percentage of total US freight ton-miles, it’s been headed up since the mid-80s:

About a year and a half ago, the Federal Railroad Administration published a report indicating that over long distances, rail is between 2-5.5x more efficient than trucking (Hat Tip: Future Pundit). I work at a trucking company, and I can tell you that intermodal – combined truck-train for long-haul shipments – is growing by leaps and bounds. Given the massive investment necessary to lay new track and secure new rolling stock, trucks continue to be a better choice for short-haul. But the best coast-to-coast operational choice seems to be rounding up the freight onto a container by truck, getting it to the railhead, and letting the train do the long-haul work. Trucks can then do the local or regional delivery at the other end. I even heard on long-time trucker complaining about this trend in the company cafeteria a few weeks ago.

I can’t remember where I saw it, but someone also poke fun at the idea of transporting oil by train. Hadn’t these people ever heard of pipelines? Aside from the apparent permitting nightmare in getting new pipelines approved, I can also tell you that the idea isn’t necessarily as ridiculous as it sounds. When were were looking at a couple of different ethanol plays at the brokerage, the need for specialized railcars was one of the drivers we took into consideration.

I initially also had thought that maybe it would have been better to focus on some newer technology rather than trains, but having seen the film, I’ve no doubt they made the right choice. Trains are visible, tangible, and connect with something very American.

The interesting thing about O’Rourke’s suggestion – that maybe they would have been better off setting the film in the 1950s – is that instead of liberating the filmmakers, it would have firmly trapped the film in past, reducing its relevance even more. Because almost everything Rand projected about trains actually happened. Unable to compete with subsidized roads, regulated to death by the ICC, trains deferred more and more maintenance, until northeast corridor rail freight virtually collapsed in the late 60s, leading to an actual government takeover and the creation of Conrail and Amtrak.

Once railroads were able to set their own rates again, they consolidated and recovered. Conrail’s operations have since been privatized, and the graphs above show the results. Union Pacific has been profitable right through the recession.

Railroads, as mentioned, do have a problem with the large capital investment necessary to expand, making them less flexible compared to trucks, just as light rail or commuter rail is less flexible compared to buses. But the idea that the country neither needs nor uses railroads just isn’t true, and fuel costs – as indicated in the film – will just make them more relevant for long-haul trips.

Notes From a Train

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PPC, Transportation, Uncategorized on April 17th, 2011

Yes, literally from a train. I’m writing this on Amtrak’s #5, the westbound California Zephyr, on my way home from Omaha for Passover.

I’ll confess a weakness for trains. In this, I’m not unlike most Americans, although unlike the Americans running the government, I recognize the economic limitations of passenger trains in a country with a relatively low population density. But hey, if I’m already subsidizing the thing, I may as well use it, especially if planes are more expensive and buses are dirtier, more expensive, and take longer. Driving, in this day of $4-a-gallon gas, just means I’m spending too much money to also lose 8 hours of productivity.

With all but the northeast corridor reduced – essentially – to tourist service, Amtrak has scheduled the dull parts of the ride at night. The train goes from Chicago to San Francisco, and as there’s a fair amount of majesty in Colorado, and not so much on the fruited plain, the segment from Omaha to Denver is mostly at night both ways. This makes it the rare practical alternative to flying. I can leave Omaha at 11:00, and (usually) be in Denver by 7:30, and leave Denver at 7:30 PM, and be in Omaha by 5:00 AM.

It’s also a better class of passenger than on the bus, even with the lower fares. The problem is sleeping. When I was just out of college, I took a long train trip from DC, up to Toronto, and then across Canada on the Canadian, all the way out to Vancouver. I came back from Seattle to Washington. Another time, I took a trip down to Orlando to visit my parents. On both trips, I got a sleeper car. (On the second one, I took my electric typewriter with me and wrote a twenty-page term paper in my berth.) I can tell you that sleeping in a chair, even when you get both of them, with a CPAP, is a somewhat different experience. In any case, train travel has always been less North By Northwest, than our romantic imaginations would imply. For one thing, in that shot, it’s the scenery that moves.

The other thing I’ve re-discovered is that it’s easier to take pictures of trains than to take pictures from trains. When you’re driving, you can stop the car, maybe double back to take a shot you saw from the road. The train frowns upon that sort of behavior. Added to that, in recent years, Amtrak has changed its rolling stock on its cross-country trains. When I took that cross-country trip, the observation car looked like this:

Now, the trains are all double-decker:

You can see the problem. When the whole train is double-decker, you can’t see ahead, you can only see out the side of the train. You can’t see as much to begin with, and by the time you see something worth photographing, your shot ends up be perpendicular to the train’s motion, leaving you with a lot of blurry pictures. It also had the side-effect of slowing us down Thursday night because of high winds, costing us about 90 minutes into Denver.

The thing is, despite the somewhat newer rolling stock, the train still has an air of faded glory. The bathrooms are clean enough, but often not fully stocked. There seem to be plenty of staff, but on the train, it’s not entirely clear what they do when not at the station. The first time back at Denver, it took 30 minutes to move the luggage across the street from the train to the station. The one thing they don’t do it grope you on the way to your destination or make you stand in line for 2 hours, and I overheard a number of conversations that indicated Amtrak was benefiting from that behavior at airports.

The fact is, the train is an anachronism. It’s fun, it’s less money and less work than flying. But because it takes more time, it’s not how people travel these days. Most cross-country routes are tourist trains, and so there’s sense of guilty luxury, in spite of the price. And if you’re going farther than overnight, the cost of a room really does turn the trip into a luxury outing. These routes couldn’t exist with taxpayer subsidies; even with a fairly good ridership, I doubt they come close to breaking even. And they’re only half-full because there’s only one train a day, which limits your options.

But if it makes economic sense, it’s still a great way to go.

.jpg)