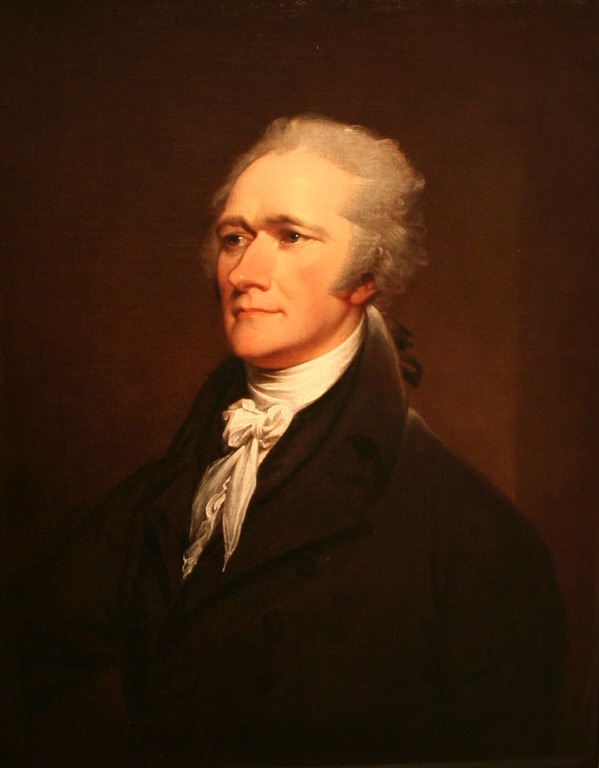

Hamilton’s Productivity

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 22nd, 2017

In his biography of Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow marvels several times of Hamilton’s capacity for work. He wrote the bulk of the Federalist Papers, sometimes turning out as many as 5 in a week. When his opponents in Congress wanted to try to hang him on unfounded corruption charges, for instance, they demanded that he produce voluminous reports on short deadlines. They underestimated him. On p. 250, Chernow describes how Hamilton was able to do this:

Hamilton’s mind always worked with preternatural speed. His collected papers are so stupefying in length that it is hard to believe that one man created them in fewer than five decades. Words were his chief weapons, and his account books are crammed with purchases for thousands of quills, parchments, penknives, slate pencils, reams of foolscap, and wax. His papers show that, Mozart-like, he could transpose complex thoughts onto paper with few revisions. At other times, he tinkered with the prose but generally did not alter the logical progression of his thought. He wrote with the speed of a beautifully organized mind that digested ideas thoroughly, slotted them into appropriate pigeonholes, then regurgitated them at will.

Both the organized mind and the regurgitation are harder than they look. They both require patience, training, and discipline. Yes, he was writing at a different time, when repeating arguments didn’t mean chewing up half of your allotted 700 words. Length was never an issue, and Hamilton, being Hamilton, was brilliant enough that neither was publication or readership. But I notice it when favorite columnists of mine no longer have anything new to say, and part of my own lack of production is from a desire to say something new each time, rather than even mentally cut-and-paste from previous efforts. Contrary to popular opinion, it takes patience to repeat yourself.

This goes hand-in-hand with having an organized mind. One wants to be able to assimilate events and ideas, and to respond to them. But there’s a concomitant risk of building a system and fitting everything into that system. One’s thinking becomes rigid, rather than supple and responsive. You see this all the time with people who reduce all political arguments to one or a handful of principles – everything becomes confirmation of those few underlying ideas, but then all arguments return to those same few ideas. Discussions become stale, because it’s more comfortable to have the discussion you’re used to having.

Breaking News From 1798

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Political History on October 18th, 2017

I may be the last person on the planet to have read Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. I’ll certainly be digesting it for a while.

Among Chernow’s contributions is a detailed discussion of the American political climate, during the Washington and Adams administrations, when the bulk of Hamilton’s contributions to the nascent government were made. It’s also when we saw the emergence of the first real political parties in history, parties committed to more than the mere attaining and retaining of power, but also to rival economic and political theories.

Today, we’re used to the stability of the two-party system, but at the time, they were not only a novelty, but a bit of a shameful one at that. The Founders had wanted to avoid factions, or parties. The new parties were not only organized around ideas, but also around the personalities of their leaders. This led to a curious combination of personal touchiness, mutual misunderstanding and hostility, and denial that it was going on at all.

From Pages 391-92 of the softcover edition:

The sudden emergence of parties set a slashing tone for politics in the 1790s. Since politicians considered parties bad, they denied involvement in them, bristled at charges that they harbored partisan feelings, and were quick to perceive hypocrisy in others. And because parties were frightening new phenomena, they could be easily mistaken for evil conspiracies, lending a paranoid tinge to political discourse. The Federalists saw themselves as saving America from anarchy, while Republicans believed they were rescuing America from counterrevolution. Each side possessed a lurid, distorted view of the other, buttressed by an idealized sense of itself. No etiquette yet defined civilized behavior between the parties. It was also not evident that the two parties would smoothly alternate in power, raising the unsettling prospect that one party might be established to the permanent exclusion of the other. Finally, no sense yet existed of a loyal opposition to the government in power. As the party spirit grew more acrimonious, Hamilton and Washington regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature.

One last feature of the inchoate party system deserves mention. The emerging parties were not yet fixed political groups, able to exert discipline on errant members. Only loosely united by ideology and sectional loyalties, they can seem to modern eyes more like amorphous personality cults. It was as if the parties were projections of individual politicians – Washington, Hamilton, and then John Adams on the Federalist side, Jefferson, Madison, and then James Monroe on the Republican side – rather than the reverse. As a result, the reputations of the principle figures formed decisive elements in political combat. For a man like Hamilton, so watchful of his reputation, the rise of parties was to make him ever more hypersensitive about his personal honor.

The parallels between the politics of that day, when parties were being formed, and today, when they have been structurally weakened and are in flux, should be obvious. The party establishments and the administrative state mitigate some of the effects, but there’s no question that election laws have neutered party back-rooms and allowed anyone to run under a party banner. The move towards open primaries further erodes party discipline. Each party increasingly sees the other less as principled opposition and more as a conspiracy bordering on organized crime. And there is no question that the Bush and Clinton dynasties, along with the personally prickly Obama and Trump, have personalized presidential politics to a degree we’ve not seen in a while.

Over the last several presidential elections, people have called attention to the vitriolic nature of political campaign rhetoric, if not (until 2016) by the candidates themselves, then by their surrogates and supporters. As often, people have trotted out some of the truly vicious things said in the campaign of 1800. With a somewhat broader view, that similarity seems less a coincidence and more like the product of a common cause.

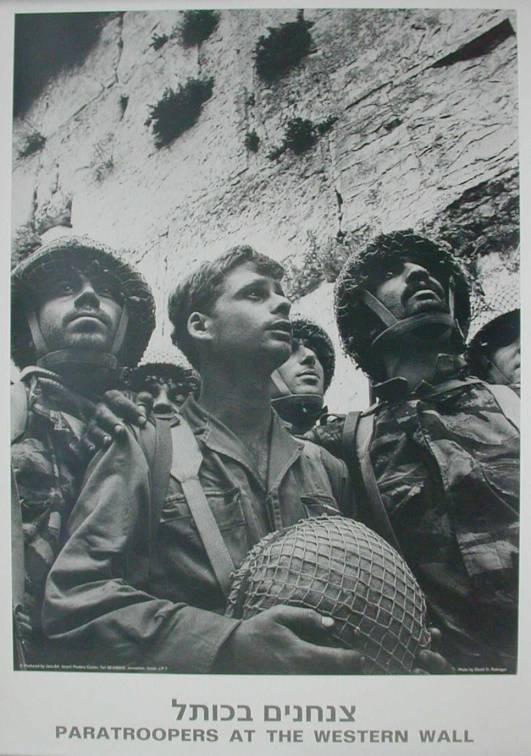

Jerusalem Day, 1967

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on May 23rd, 2017

Tonight marks the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Old City and reunification of Jerusalem by Israeli forces in the Six Day War. That event marked the first time that Jerusalem and its holy places had been under Jewish sovereignty in 1900 years.

Tonight marks the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Old City and reunification of Jerusalem by Israeli forces in the Six Day War. That event marked the first time that Jerusalem and its holy places had been under Jewish sovereignty in 1900 years.

And yet, when the war started, taking the Old City was on the minds of very few Israeli Jews. Certainly not on the mind of Moshe Dayan, newly-installed Minister of Defense. Certainly not on the minds of the troops.

Jordanian artillery had been shelling the western half, the Jewish half, of the city as well as part of the coastal plain farther north, since the start of the war, but the Israeli government felt that it could more or less overlook this. Jordan’s British-trained Arab Legion was among the best-led and most disciplined of the Arab armies, and it had been supplemented by some crack Egyptian units. For Israel, the main front was, as in 1956, the Sinai, and it simply didn’t have the resources for a two-front war.

Only when Jordan moved to take over Government House, a UN post guarding the road to the southern entrance to Jerusalem, did Israel feel that it might have to move.

Even then, the Old City was off limits. The orders were to take the high ground surrounding the city, from where the Jordanian artillery was firing.

Dayan, while not religious, felt a deep, profound historical ownership of the land, and wanted the Old City back as much as anyone. His worries were twofold. First, the density of religious sites and population was such that a firefight could end up killing a lot of civilians, and damaging those sites. Bullet holes in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher or mortar rounds ending up in the side of Al Aqsa would be objectively bad, and would also likely provoke a reaction on the part of the rest of the world.

That let to Dayan’s second concern. He had seen how military victory in 1956 had been turned into political defeat, when Israel had been forced to surrender the Sinai in return for useless UN peacekeeping guarantees. He feared to blow to Israeli morale should they take the Temple Mount and Western Wall only to be forced to give them back.

In the end, air power proved militarily decisive. After a difficult night of confused fighting, Israeli planes pounded the Augusta Victoria Ridge for much of the morning before the troops slogged up the hill to take it. When they reached the summit, the Jordanians had fled, and with no fire coming from inside the Old City, it was reasonable to believe those troops had fled as well. This mitigated Dayan’s first fear, and he gave the order to take the Old City.

As for Dayan’s second fear, it wasn’t realized either, at least not immediately. But one need only look at UNESCO and the Arabs and UN Resolution 2334 to know that they have not yet surrendered the idea of driving the Jews from their home.

Bennet Takes the Path of Least Courage on Gorsuch

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, National Politics on April 4th, 2017

Colorado’s Senator Michael Bennet has announced that he will not support the Senate Democrats’ filibuster of Gorsuch’s nomination, but that his vote on the nomination itself will depend on whether Senate Republicans move to change the filibuster rules, in which case all bets are off.

Conveniently, Bennet’s announcement came just as Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer claimed to have the needed 41 votes to sustain the filibuster.

Bennet has been under pressure here in Colorado to support Gorsuch’s nomination, for two obvious reasons – Gorsuch is unquestionably qualified for the Court, and he’s a fellow Coloradan. (In fact, Gorsuch’s childhood home is just a few blocks from where I live now.) This approach allows Bennet to maximize political posturing, while allowing others to do all the heavy lifting.

This is, perhaps, the most pointless partisan filibuster in all of history. Majority Leader McConnell has all but announced his intention to change the Senate rules to ditch the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations, the last remaining nomination filibuster permitted. In doing this, he is doing no more than Harry Reid intended that Chuck Schumer do, when the Democrats expected to retake the Senate and retain the White House back in November.

Bennet’s position allows him to pretend that he opposed the filibuster that forces McConnell’s hand, while knowing that other Democrats will carry that filibuster on without him. Then, he can avoid the question of Gorsuch’s merits by pretending to be outraged by the inevitable rules change.

It’s classic Bennet, who expressed doubts about the Iran deal, even playing on his own Jewish background, but then threw up his hands, shrugged, asked, “What can you do?” and voted to sustain the Senate Democrats’ filibuster of the resolution of disapproval, so as to avoid a recorded vote on the merits.

Bennet, always one to conserve political courage for another day, has stayed true to himself in his decision.

Why PERA’s Cumulative Returns Matter

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on March 9th, 2017

PERA’s unfunded liability often comes into sharper after a year of low returns. Its detractors point to last year’s 1.5% return, for instance, as evidence that PERA’s expected rate of return is too optimistic (it is). Its defenders argue that a single year’s returns are less important than the long-term (they are). They then point to a time frame, say, the last 7 years, where PERA has averaged 9.7%.

But it’s not just average returns that matter. It’s cumulative returns, and there, even a couple of bad years can wreak havoc on a defined benefit plan.

Let’s look at PERA’s returns since 1990:

A few really bad years to start off the century, and we all remember 2008. But aside from that, mostly above expected, and a few years slightly below expected. If you had invested $100 in PERA Mutual Fund in 1990 and let it sit for a quarter century, you’d be about where you should be, based on each year’s expected rate of return. Most years, you’re even ahead of the game, before the dot-com burst and the housing bubble burst bring you back to earth.

But of course, you don’t put $100 in in 1990 and let it sit. You put $100 in every year. Instead of looking at this from the perspective of each year going forward, let’s choose the perspective of 2015 looking back at each year. That is, for each year where you’ve invested $100, let’s see how you end up in 2015.

For $100 invested in 1990, you’d expect to have about $800, and we already know that that’s what you’ve got. For $100 invested in 2000, though, you’d expect that to be worth $355 today, but it’s only appreciated to $228. That’s because in January 2000, you invested before the bad years of 2000-2002. So money invested in every year from 1995-2003 is worth less now than PERA’s expected return would project. In fact, there are only a few years where the cumulative return through 2015 is better than expected, because 2000-2002 and 2008 wipe out all the gains beyond expectations.

Not surprisingly, this means that your PERA Mutual Fund is short of expectations in 2015, by just over 9%. You’d expect to have just over $9000, but instead you’re just under $8200.

Naturally, PERA’s actual situation is much more complex than this. But the point remains – it’s not enough to do as well as you’d expect over a long period of time, even in the absence of required annual payouts. In order to keep the plan solvent, you need to do better than that.

Russia Elects A US President

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2016 Presidential Race, History, National Politics on March 7th, 2017

In 1960. At least that’s what Khrushchev thought.

In 1960. At least that’s what Khrushchev thought.

Khrushchev took a particularly keen interest in the 1960 US presidential election. Having engaged Nixon in the famous 1959 “Kitchen Debate” while on tour in the US, he became convinced that the firm anti-Communist would be impossible to do business with. He determined to help elect whoever the Democratic nominee was.

First, he tried to convince Adlai Stevenson to run again. Stevenson declined to openly seek a third straight nomination, mostly out of pride and a desire to be asked rather than have to ask. But he was certainly not about to be goaded into it by the Soviets.

Then, when John F. Kennedy became the nominee, Khrushchev tried to intervene in the election on his side. Quoting from Dan Carlin’s podcast on the Cuban Missile Crisis:

In the book Inside the Kremlin’s Cold War by Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov, it’s interesting to read exactly how much Khrushchev was hoping Kennedy would become the president. But not because he thought he was weak, but because he thought he might be another Franklin Roosevelt, someone who could reach out and have another relationship the way Stalin’s and Roosevelt’s relationship was seen to be.

Khrushchev apparently did everything he could to help Kennedy get elected. He told KGB officers in Washington to analyze the situation, and if there was anything they could do diplomatically or with propaganda to help, to do it. He called Kennedy, ‘his president’ after he was elected, and told Kennedy at the first eye-to-eye meeting they every had, ‘I got you elected.’

Zubok and Pleshakov go on (p. 238) to detail that they were rebuffed when they rather clumsily tried to approach Robert F. Kennedy directly. However,

In the end, Khrushchev did influence the U.S. presidential elections by his belligerent rhetoric, as well as by demonstrating that a constructive U.S. – Soviet dialogue would be impossible so long as Eisenhower or Nixon remained in the White House. Twenty years before the revolutionary leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran used American hostages to influence a U.S. presidential campaign, Khrushchev did the same by holding captive two pilots of the U.S. reconnaissance plane RB-47, shot down in July 1960 over the Soviet North. Along with fears of the “missile gap,” Kennedy successfully exploited the issue of the captive pilots in his barbs against the Eisenhower-Nixon administration.

Correctly or incorrectly, Khrushchev believed this was a decisive factor in the elections. From his memoirs, Khrushchev Remembers, page 458, he details how he mentioned this to Kennedy at the Vienna summit:

By this time President Kennedy was in the White House. Not long before the events in Berlin came to a head, I met Kennedy in Vienna. He impressed me as a better statesman than Eisenhower. Kennedy had a precisely formulated opinion on every subject. I joked with him that we had cast the deciding ballot in his election to the Presidency over that son-of-a-bitch Richard Nixon. When he asked me what I meant, I explained that by waiting to release the U-2 pilot Gary Powers until after the American election, we kept Nixon from being able to claim that he could deal with the Russians; out ploy made a difference of at least half a million votes, which gave Kennedy the edge he needed.

Of course, at the time, nobody accused RFK or JFK of actually colluding with the Soviets to ensure JFK’s election. (That would have to wait for another election, and another Kennedy.)

Pension Sabermatrics

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 21st, 2017

We need new pension metrics.

In the 1980s, baseball writer and analyst Bill James recognized that the traditional baseball statistics, like Batting Average, RBI, and Runs Scored, were so severely limited as to be wildly misleading. Batting average didn’t distinguish between home runs and singles, and didn’t count walks at all. RBI depended heavily on batters in front of you getting on base. Likewise Runs Scored depended heavily on batters behind you driving you in. Park size influenced ERA. Slow fielders got to fewer batted balls, so paradoxically recorded fewer errors. And so on.

By writing and thinking and analyzing what data was available, James created entirely new stats, intended to isolate individual performance, or tease out surprising results about team performance. So now we have the “Slash Line,” of Batting Average, On-Base Percentage, and Slugging. We have Runs Created, Park-independent ERA, and Range Factor. James created a whole new field of baseball analysis, and now there’s not a major league team without an analytics department using them to evaluate team and individual performance.

In the last few years, the country has had a growing realization that its public pensions are in trouble. Communities, struggling to meet unrealistic commitments that by and large their members didn’t make, have undertaken a series of reforms to existing defined benefit programs, and have even been converting those plans to 401(k)-style defined contribution and cash balance plans.

But in doing so, policymakers are still guided by a small number of traditional metrics that give only a vague sense of a plan’s health, and little if any guidance on potential fixes.

Right now, policymakers focus primarily on Funded Status and Amortization Period. The first tells you how much money a fund has on hand to cover promises made, in present-day dollars. The second tells how long it would take to reach fully-funded status. But each has severe limitations. A plan’s funded status is a snapshot of where it is right now, but does nothing to capture the trend, or the risk that things will get worse. The Amortization Period helps describe how far off-track a plan is, but quickly becomes extremely sensitive to small changes in plan dynamics.

Much like baseball in 1980, public pension analysis is ripe for new statistics. Over the last few years, plans’ financial reports have become more detailed and include more historical information, so there’s much more information for analysts to work with. This shouldn’t just be playing games with numbers; new statistics should be designed to help policymakers, plan managers, and citizens understand how bad the problem is, and where the risks to their plans lie.

Here are the criteria I propose:

- Each statistic should be a single number

It shouldn’t have error bars, or only be understood in combination with other numbers. A full analysis should require more than one number, but Slugging Average means something by itself, it doesn’t need other numbers to make sense. - It should have a clear meaning and definition

People should know what they’re looking at, and understand exactly what the number is meant to describe. - We should be able to calculate it, or at least estimate it, from publicly available information

Reproducibility is key. We shouldn’t have to rely on pensions to make these calculations for us, or for legislatures to commissions studies, and we should be able to ding plans that start removing useful data from their reports

At the same time, it’s important to keep in mind what we’re not trying to do:

- There is no Holy Grail here

We’re not looking for a single Public Pension Score that captures everything. There will be numbers that are more desriptive, statistics that encapsulate more information, but there’s no reason to create some artificially-weighted “Pension Health Score” that tells you too much while telling you nothing at all - Closed Definitions

There can be debate on the best way to calculate these numbers. There are very strong competing opinions about the proper discount rate to use, for instance, or the proper tax base, and so on. Those are legitimate debates to have. We’re striving for clarity, not absolutism - Fairness Metrics

Recent studies such as one by the Urban Institute have also looked at pension fairness, and how well a pension plan performs its functions. That may help in making the political case, but it’s outside the scope of what I’m proposing here.

In 2014, the Colorado legislature mandated a sensitivity study of PERA. As part of that study, the consulting firm developed a simpler, “Signal-light” structure, that included calculations of a plan’s risk of going broke over a period of time, based on variations in investment returns. That’s an example of a great, simple number that encapsulates a great deal of information and helps policy-makers decide the risk to their communities.

It’s a good start, but I’m pretty sure we can do better. For one thing, while the methodology behind that calculation may be fairly simple, it’s almost impossible to recreate it without developing a complex actuarial model of the pension plan. That might be an interesting and useful exercise, but it breaks requirement #3.

Just sitting down and brainstorming, I came up with a list of a few metrics that might be useful, as a starting point.

- Projected Inflow vs. Outflow using projected rates of return, based on historic rates of return

- Liability vs. State (or Jurisiction) GDP

- Unfunded Liability vs. Jurisdiction GDP

- Liability vs. Tax Rates

- Liability vs. Overall Jurisdictional Budget

- Required rate of return to lower the amortization period

- Effects of increased risk on likelihood of ruin

Real analysis would whittle down from a list a of 20 or so but the purpose here should be obvious. How much flexibility is there in the jurisdiction’s finances to deal with its problem? Can it cover current costs? Can it raise taxes to cover them? How big a bite out of actual services is the pension contribution taking?

There’s enough good information out there now that we don’t need to keep flying blind.

PERA Admits Problem – Blames Legislature

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on January 4th, 2017

Could people be catching on to the shell game / ponzi scheme that is Colorado’s public pension system? If the Denver Post can start running critical articles, then anything’s possible.

Could people be catching on to the shell game / ponzi scheme that is Colorado’s public pension system? If the Denver Post can start running critical articles, then anything’s possible.

Yesterday (“‘Alarm bells’ raised: PERA stability again under scrutiny“), the Post noted that even PERA is admitting that it’s going to take longer to reach fully-funded status than had been previously estimated.

Wow! Who could have predicted this? It’s a shame nobody’s been around to tell them this might happen.

PERA is paying particular attention to the Judicial Fund, which is projected never to crash and burn, but never to achieve fully-funded status. It’s like a pension version of Purgatorio. We’ve been here before with larger funds, and indeed, the Denver Public Schools Fund also has an infinite amortization period.

The Judicial Fund is tiny. The DPS fund isn’t huge itself. The state could easily just pay these pensions out of current cash.

The State and School Funds, however, are gigantic by comparison, and have the potential to crush state and school budgets. Their amortization periods are now around 45 years, and headed in the wrong direction. The amortization period varies wildly with relatively small shifts in return because we’re operating so close to the margin. It’s not the 10 year shift itself that’s worrisome, it’s the fact that we’re so close to infinity to begin with.

PERA with good amortization. A small difference in the funded level doesn’t change the date much. This is ok, as long as you don’t drift too far off center.

PERA with bad amortization. A small difference in returns sends you first to the brink, and then spinning off into space, helpless, never able to retire. You just don’t want to be operating in this region.

PERA, like most public pensions, relies on “time diversification,” or the idea that over the long term, average expected returns are the best guide to what will happen. But they’re not the best guide to what the risk is to the fund, the retirees, and the citizens of the state. The paradox is that even as average returns converge, where you end up at the end of 30 or 40 years spreads out.

It’s like the pension version of “gas expands to fill the available space.” Imagine if I brought a canister of chlorine gas into the room and took the top off of it. Sure, the center point would stay the same, but pretty quickly we’d be all DIA murals.

In the same way, the expected returns converge to the mean, but the number of things that can happen, the number of different balances you can end up with, grows, and therefore so does the risk of one of those balances being negative.

PERA itself has acknowledged this. Its own study in 2015 showed a better than 1-in-6 chance that the School and State Funds would crash and burn sometime in the next 30 years, based solely on variations in expected returns:

When PERA runs into trouble, it will likely be because of low investment returns. The state will then likely try to come to the taxpayers to bail it out. It may even be forced to do so by the courts.,

The problem is, the taxpayers have their retirement money in mostly the same places of PERA, and will have also been seeing low returns on their own retirement portfolios. Basically, the state will be demanding money from people who don’t have it, in order to honor promises they didn’t make.

As a taxpayer, I’m mad. But I’d also be mad if I were in the legislature. Here’s PERA Executive Director Greg Smith:

“You all put together a 30-year plan to recover from that,” Smith told lawmakers. “We’re six years in, and we’re behind. And we’re going to go and talk about how can we get back on track for what that plan was.”

“You all?” Yes, that’s true. The Legislature had to vote on the plan. But it was informed by PERA’s Board, who not only backed SB1, but also had a huge part in drafting it and commenting on its provisions. Every year, every time the question has come up, PERA’s Smith has said that things were just fine. Every time anyone proposed changes to make it more robust – better reporting, small tinkering at the edges, larger more substantive improvements – PERA’s Smith has been there with his merry band of union and retiree groups arguing against them.

This is Exhibit A of why we need to move to a defined contribution plan and take these decisions out of the hands of elected officials. Legislators aren’t (all) dumb, but they’re not specialists, and they rely on experts like Smith to inform them about what needs to be done. But Smith and PERA as a whole have a vested interest in telling them that everything is fine, or that more money from taxpayers will fix the problem.

Moving to a 401(k)-style plan, or even a cash balance plan, would help insulate everyone from the politics here.

La-La Land

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on December 25th, 2016

There’s a scene in the new musical La La Land where jazz pianist Sebastian, played by Ryan Gosling, is confronted by his old friend and band-leader, Keith (Jon Legend) about the nature of jazz. It’s after Sebastian’s first practice session with Keith’s new band. Sebastian is convinced jazz is dying because people won’t take it on its own terms. Keith replies that Sebastian talks about saving jazz, but that to do that, you have to bring it up to date with synthesizers and backup singers, not be a slave to its history. But Sebastian isn’t trying to put jazz in amber, he just wants it to be confident in its own authenticity.

There’s a scene in the new musical La La Land where jazz pianist Sebastian, played by Ryan Gosling, is confronted by his old friend and band-leader, Keith (Jon Legend) about the nature of jazz. It’s after Sebastian’s first practice session with Keith’s new band. Sebastian is convinced jazz is dying because people won’t take it on its own terms. Keith replies that Sebastian talks about saving jazz, but that to do that, you have to bring it up to date with synthesizers and backup singers, not be a slave to its history. But Sebastian isn’t trying to put jazz in amber, he just wants it to be confident in its own authenticity.

Keith and Sebastian are talking about jazz. And about the movie musical.

The central artistic tension of the film is between nostalgia and creativity. Both writer-director Damien Chazelle and his on-screen avatar Sebastian struggle with how to draw on the goodwill and good feelings of a golden age, while not getting trapped in stagnant nostalgia. This year saw a number of films set in Hollywood’s golden age that didn’t work well. I had high hopes for the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar!, but it failed precisely because it was post-modern nostalgia, and homage rather than a creation.

Chazelle solves the problem by not making a period piece. It’s set in 2016, but follows the conventions of the traditional musical.

La La Land works because it’s confident in its own authenticity. From the opening production number set in a traffic jam on an LA freeway, the characters simply slide into singing or dancing because that’s what characters in musicals do. The musical numbers advance the plot or develop the characters because that’s what musical numbers do.

Gosling and Stone don’t wink at the audience. Hip irony, or self-aware self-consciousness would kill the picture, because if a film doesn’t take its own form seriously, why should you?)

The musical is actually melodic and enjoyable, legitimate 21st Century show tunes, not rock or rap shoehorned into a mismatched genre. You recognize Seb & Mia’s theme when it’s repeated; the recurring ballad, a rhythm song named “City of Lights,” works in any tempo or mood, and isn’t so overworked that you get sick of it.

And oh, do you take it seriously. There’s plenty of humor, of course, but through the first 120 minutes, right up to the climactic “Epilogue,” you first believe in Seb and Mia, and then invest heavily in their relationship. Each of them is charming in their own right, but the chemistry between them pops off the screen. You desperately want them to succeed as individuals and as a couple.

Therein lies the central relationship tension of La La Land – can they have both their creative dreams and their dream of each other?

By setting a traditional music today, and by writing for a 2016 audience, Chazelle really does keep you guessing up until the very end. Some will find the ending satisfying; to others, it will look like the easy way out.

But sorry, no spoilers here. You’ll have to see it yourself.

Sen. Gillibrand Does History

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on December 2nd, 2016

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) has tweeted out that she won’t support a law allowing Gen. Mattis to serve as Secretary of Defense with 7 years of his military separation, because she believes in civilian control of the military. Nobody I know disagrees with the principle, and there’s plenty of civilian control built in, starting with the fact that Mattis himself is now a civilian, as is the incoming president, and most of the members of Congress.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) has tweeted out that she won’t support a law allowing Gen. Mattis to serve as Secretary of Defense with 7 years of his military separation, because she believes in civilian control of the military. Nobody I know disagrees with the principle, and there’s plenty of civilian control built in, starting with the fact that Mattis himself is now a civilian, as is the incoming president, and most of the members of Congress.

Maybe Gillibrand needs a history lesson.

The only other time such a law was needed was when former Gen. George Marshall moved from the State Department to Defense under Pres. Truman. Marshall, for the benefit of Sen Gillibrand, was the author of something called “The Marshall Plan,” which saved much of Western Europe from Communism by helping it to rebuild after World War II. Truman asked him to serve as Secretary of Defense during something called “The Korean War,” which saved South Korea from Communism by defending it against the Chinese and Russians.

Pres. Truman knew a thing or two about civilian control of the military. For instance, during the Korean War, he found himself standing up to and relieving the popular Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who thought he knew enough to dictate the scope and terms of the war to the president.

Gillibrand’s about my age and got into Dartmouth at a time when the Ivies hadn’t descended into madness, so I assume she’s familiar with at least some of these facts. (In case she’s not, she’s got a 50th birthday coming up in a week; maybe someone can buy her David McCullough’s biography of Truman for a present.)

More likely, she’s posturing as a leader of The Resistance, positioning herself for a 2020 White House run. Rumor has it that she’s already been contacting Clinton donors with that possibility in mind. She may also remember 1989, when Democrats torpedoed the nomination of fellow Senator John Tower for Defense Secretary, and believe that this is a road to weakening a President Trump at the outset.

It may play well with her base, and with the party, which is where she needs to start. But Gen. Mattis is revered among his troops and admired by the public at large. Starting with an attack on his nomination might not be the swiftest move in the long run.