Bruce Catton and U.S. Grant

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, History on March 25th, 2018

Having finished Ron Chernow’s biography of Grant, I decided to go back to my library and re-read Bruce Catton’s shorter treatment of the subject, U.S. Grant and the American Military Tradition. Catton did most of his writing in the 50s and 60s, so some of the scholarship is dated, but most of his conclusions have held up.

More than that, Catton’s writing verges on the poetic, both summarizing and illuminating a subject with an economy of words I often wish I had. For instance, in describing frontier Ohio of the 1820s and 1830s:

Men who could do everything they chose to do presently believed that they must do everything they could. The brightest chance men ever had must be exploited to the hilt. And the sum of innumerable individual freedoms strangely became an overpowering community of interest.

When dissecting the rights and wrongs of secession, its present-day defenders (who do not defend the institution of slavery, it should be emphasized) tend to focus on the clinical, legal aspects of the matter. Catton captures what they miss, and why the North and especially the West was willing to fight:

Against anything, that is, which threatened the unity and the continuity of the American experiment.

Specifically, they would see in an attempt to dissolve the Federal Union a wanton laying of hands on everything that made life worth living. Such a fission was a crime against nature; the eternal Federal Union was both a condition of their material prosperity and a mystic symbol that went beyond life and all of life’s values.

On the post-Shiloh commanders:

McClellan, Halleck, and Buell, then, were the new team, and that hackneyed word “brilliant” was applied to all three. The Administration expected much of them. It had yet to learn what brilliance can look like when it is watered down by excessive caution and a distaste for making decisions, and when it is accompanied every step of they way by a strong prima donna complex.

And on how Americans view war. Catton believes it goes a long way towards explaining why Grant – representative of his people – was doomed to substantially fail at the big post-war task of Reconstruction and restoration:

…the will-o’-the-wisp again, recurrent in American history. Victory becomes an end in itself, and “unconditional surrender” expresses all anyone wants to look for, because if the enemy gives up unconditionally he is completely and totally beaten and all of the complex problems which made an enemy out of him in the first place will probably go away and nobody will have to bother with them any more. The golden age is always going to return just as soon as the guns have cooled and the flags have been furled, and the world’s great age will begin anew the moment the victorious armies have been demobilized.

Sound familiar?

Catton was not, of course, infallible. He had this to say about President-Generals, whose training is to treat Congress as supreme, the executive as the instrument of Congress’s declared war aims:

It made it inevitable that when he himself became President he would provide an enduring illustration of the fact that it can be risky to put a professional soldier in the White House, not because the man will try to use too much authority in that position but because he will try to use too little.

Catton wrote these words in 1954, with full awareness of who was then president. But history doesn’t bear out his fear, entirely. Washington maintained a strong sense of the office’s limitations, but worked to strengthen both the federal government and the executive. Neither of the two previous Whig presidents – both generals – lived long enough to have much impact in the office. And Eisenhower was working with an already-stronger executive, which he worked to professionalize, treating his cabinet a little like a corporate boardroom of competing ideas.

He differs with Chernow on a few points, and Catton is somewhat better at drawing connections. Catton considers the Santo Domingo treaty not merely ill-advised but actually corrupt, for instance. Both note that Grant manumitted the one slave he ever owned as quickly as he could (a gift), but only Catton points out that Grant did so even though he could really have used the money from a sale at that point in his life.

Catton is also harder on the Radical Republicans, and somewhat more forgiving of Andrew Johnson, than Chernow is, possibly because Catton was unaware of the postwar wave of white supremacist violence that swept over much of the Deep South. He argues that the Radical Republicans were at least as interested in using blacks as a means to political power as they were in their welfare – not the last time that would happen in American history. Catton also claims that Johnson adopted Lincoln’s view of postwar reconciliation, where Chernow states that Johnson adopted a softer line through misbegotten racial solidarity. Whether this is from cynicism or greater political savvy, or from both, it’s hard to know.

SB200 and PERA Reform – The Good, The Bad, and The Missing

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on March 23rd, 2018

Today, the State Senate is scheduled to debate SB18-200, the PERA reform bill, on the floor. As befits a big, complicated problem, it’s a big, complicated bill. As with any big, complicated bill it’s a mix of good and bad. In this case, there are also elements that are missing that would vastly improve the bill’s effectiveness and fairness.

And as with any bill, especially one in a divided legislature, there are political considerations. The bill is the result of several months of bipartisan effort, led by Republican Sen. Jack Tate and Democratic Rep. K.C. Becker, but also with the contributions of several Democratic senators and Republican representatives.

The Good

Photo Credit: Todd Shepherd

The Good in SB200 can be broken down into three parts. First, there’s the usual dial-turning and knob-twisting, but in this case, there’s also some screw-tightening and refitting. Second, there will be expanded legislative oversight. Third, there will be an expansion of the Defined Contribution plan. Let’s take each of these in turn.

The Dials and Knobs

The bill will increase contributions and decrease benefits in a number of ways:

- Employee contributions will step up another 3%

- Contributions will be calculated on gross, rather than net salary, reducing the incentive to game the system through deductions and spiking

- The Highest Average Salary will be calculated on 7 years, rather than the current 3 years

- COLAs will take a 2-year break, and then will max out at 1.25% per year

- The retirement age will increase to 65 for new and younger employees

- If needed to keep the plan on track, employee contributions and COLAs will be adjusted automatically

The retirement age increase and the COLA limits have been the main targets of PERA members, for obvious reasons. COLA limitations put almost all the inflation risk on retirees. Adjusting the retirement age for new employees is relatively uncontroversial – there is no group less organized than those who have not yet decided to sign an employment contract. But adjusting the retirement age for existing employees, even younger employees who have time to adjust, will have to be tested in the courts to see whether that’s considered enough of a “core” benefit to resist change.

Increased Oversight

The bill also calls for the creation of a new joint legislative committee, composed of six House and six Senate members, three from each of the caucuses, specifically to oversee PERA. The committee would also have four non-voting outside experts appointed by the Treasurer. Creation of this committee would create an in-house body of expertise, much like we have with the Joint Budget Committee, and which is lacking the legislature now. It would also allow outside experts to grill the Board publicly and hold it accountable – at least in words – for the effects of its decisions and recommendations.

Defined Contribution

Currently, State employees – but not teachers or other PERA members – have the option to choose the Defined Contribution plan when they join PERA. This bill would extend that option to all new PERA members, and it is one of the most reviled parts of the bill as far as PERA and the unions are concerned. They believe that it will work to undermine the DB plan, but they say that as though it were a bad thing.

The Bad

The bad was the increase in the employer (read: taxpayer) contribution. The original bill would have increased that by 2%, when employers are already putting in 20.15% of salary. For school districts who are already paying upwards of 1/8 of their operating expenses into PERA, this would tighten budgets even further. Small governments and municipalities would also be looking a 23-25% of salary going into PERA. Fortunately, this was amended out of the bill in the Finance Committee on a party-line vote.

So, if there’s only good, and not much bad, why isn’t the Independence Institute full-throatedly behind the bill? Because of…

The Missing

We believe that, as it stands, the bill can do some good, but represents a potentially substantial missed opportunity to do more to solve the problem over the long term.

Obviously, our preferred DC/DB mix would be to get rid of the DB option for all new employees to keep from perpetuating the problem into the future. That would still leave the unfunded liability of $50 billion to be dealt with. We would also like to see an option for current PERA members to change their choice and go to the DC plan. This could be done in a cost-neutral way, where members only take their own contributions and the actuarial value of their vested benefits with them, and PERA would be able to set the price.

Barring that, we would have preferred an entirely new, more conservative DB plan with no employee contribution above the normal cost, and separate accounting for employer contributions going to the normal cost and the unfunded liability.

The bill implements neither of those. At a minimum, therefore, the defined contribution should be the default option, rather than the defined benefit. In the first place, the default option tends to be “sticky,” meaning that people tend to stick with what they’re put into as a default. Leaving the DB as the default will tend to minimize DC participation. That leads to a potential political problem down the road, where low DC participation is cited as a reason to yank the option altogether.

Second, the new oversight committee is the minimum of governance reform. But it isn’t Board reform, nor does it prevent the Board from using public money to lobby the legislature for or (mostly) against additional proposed reforms. Allowing the Board to lobby against additional reforms raises the stakes for this bill, which is bad, but also increases the likelihood that we’ll end up back in the same place in a few years.

Last, PERA needs to take some accounting measures to keep itself on track. Namely, it should seek more outside advice than just its actuaries when estimating its expected rate of return. It should ask multiple investment firms to provide estimates of how well its current portfolio will do. It should also decouple its discount rate from its rate of return, using something like the Muni 20 Index. It will only do these things if required by law. For those who dismiss these requirements as details, we should remember that the current crisis was initiated when PERA lowered its expected rate of return from 7.5% to 7.25%. And for the knobs and dials to mean anything, the discount rate and rate of return need to reflect reality as well as they can.

We doubt that if a fix is passed, there will be any appetite in the short-term to pass additional reforms. PERA and its allies will reprise their call to let the current reforms work, as their did with SB-1 for the last 7 years. This bill is the chance to get things right, so let’s do that.

UPDATE: The Senate fought back floor amendments to raise the COLA cap and to restore the employer contribution. When the Senate adjourned, it was considering a “strike-through” from Sen. Kagan that would have replaced the proposed reform plan with one essentially written by the unions. That amendment would restore the employer contributions, raise the COLA cap, lower the employee contribution increase, retain the current retirement age, and eliminate the DC expansion. It will resume consideration of the bill and the amendment on Monday.

While it is likely that this amendment, along with all others to weaken the bill, will fail in the Senate, they also provide a preview of amendments that will be offered in the House, both in the Finance Committee and on the floor. Whether those amendments pass and force the bill to a Conference Committee will be the result of the efforts to defend against them by Reps. Pabon and Becker, and the level of commitment by Speaker Crisanta Duran to the bill’s integrity.

Civil Unrest, Not Civil War

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 4th, 2018

Among many conservatives, Civil War is in the air. For many, there’s a sense that things as they are now cannot go on. The civil order as we have known it is broken, and that things will end either in organized violence or in a semi-violent divorce.

Conservatives should remember not to immanentize the eschaton.

Instead of looking to the decades leading up to 1861, we have a far closer parallel with another decade – the 1790s.

Read this, from a 1961 number of American Quarterly, “Republican Thought and the Political Violence of the 1790s,” by John R. Howe, Jr.:

By the middle of the decade, American political life had reached the point where no genuine debate, no real dialogue was possible for there no longer existed the toleration of differences which debate requires. Instead there had developed an emotional and psychological climate in which stereotypes stood in the place of reality. In the eyes of Jeffersonians, Federalists became monarchists or aristocrats bent upon destroying America’s republican experiment. And Jeffersonians became in Federalist minds social levelers and anarchists, proponents of mob rule. As Joseph Charles has observed, men believed that the primary danger during these years arose not from foreign invaders but from within, from “former comrades-in-arms or fellow legislators.” Over the entire decade there hung an ominous sense of crisis, of continuing emergency, of life lived at a turning point when fateful decisions were being made and enemies were poised to do the ultimate evil….

In sum, American political life during much of the 1790s was gross and distorted, characterized by heated exaggeration and haunted by conspiratorial fantasy. Events were viewed in apocalyptic terms with the very survival of republican liberty riding in the balance.

Sound familiar?

Gordon S. Wood, in his magisterial Empire of Liberty notes that friendships were broken, there was political violence on a local scale scattered throughout the country. Everyday life and even religious affiliation became increasingly politicized. While this happened at the beginning of parties, those parties were largely organized around the personalities of their respective leaders, Hamilton and Jefferson.

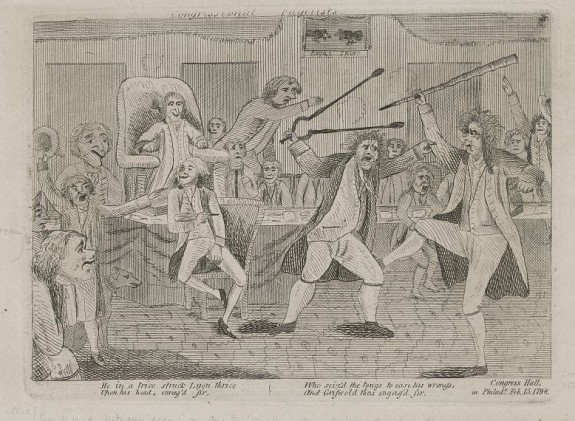

Jefferson’s Republicans didn’t necessarily expect to win in 1796, but the loss was clearly disappointing. In response, they adopted tactics that can only be described as resistance. They retreated to the state governments as bulwarks against what they saw as a too-powerful central government. They openly talked about states nullifying federal laws they considered unconstitutional. That picture accompanying this post? That’s from a fistfight on the floor of the US House of Representatives.

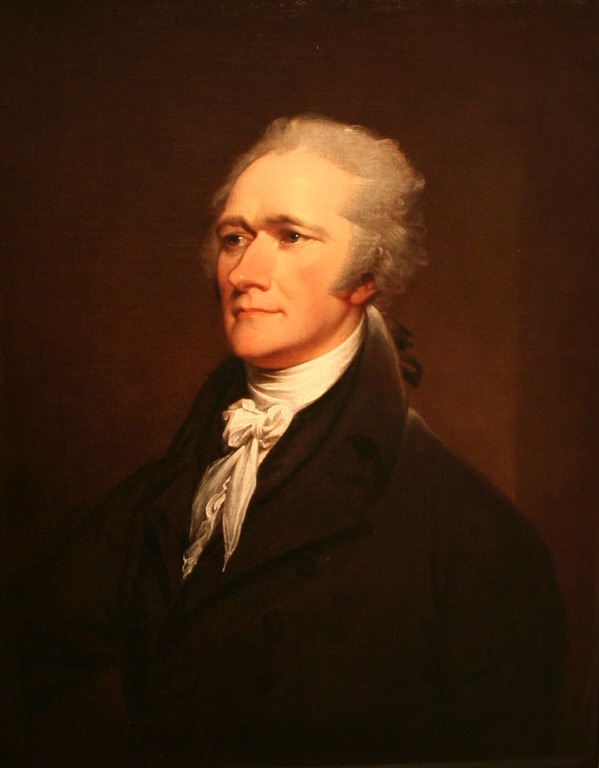

The Federalists, whose real leader wasn’t President Adams (who saw himself above parties), but Alexander Hamilton, continued to govern as though the government were simply the government, and any organized opposition to it was akin to treason. They reached out not to allies, but to the local or state elites to fill appointed posts and run for office. Instead of organizing, they wrote opinion pieces for the newspapers, and letters to each other.

Ultimately, it was organizing that brought the Republicans to power nationally. Aaron Burr’s efforts in New York tipped that state’s legislature, and thus its electoral votes, to the Republicans, and put Jefferson over the top. The Republicans would win the next six consecutive presidential elections, even as the part fragmented into regional and ideological factions of its own.

The Federalists were down, but not really out until the elections of 1816 and 1820. The conflict between the parties was resolved when the Federalists, by then almost exclusively concentrated in New England, ended up on the wrong side of the War of 1812. They worked to break the embargo and trade with Britain. They rediscovered their small-f federalist principles when their state militias frequently refused to cross the border into Canada. Old line churches often actually prayed for British victory.

By the end of the war, the country had a renewed sense of nationhood, and had turned away from Britain in the east, and towards its own future in the west. In 1789, almost all Americans had once been British subjects; by 1815, only those over 40 had, and even fewer could remember that time.

Neither the ideologies nor the tactics nor the self-identification with an “aristocracy” cut as cleanly today as they did in 1796. That’s less important than the fact that the conflict was eventually resolved, peacefully among Americans, even if it did require a war. Right now, the question of which issue will be the ultimate dividing line, which party is more in touch with the body politic, which one will emerge to create a durable, long-term majority, is still very much up in the air.

Talking Down the Dollar

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on January 25th, 2018

The dollar has been weakening over the last year. I tend to like a strong dollar, so I don’t like to see the President or the Treasury Secretary talking the dollar down, as the expression goes. I understand the impetus – it makes exports easier, which should help employment. But of course, you’re also being paid in depreciated dollars.

The dollar has been weakening over the last year. I tend to like a strong dollar, so I don’t like to see the President or the Treasury Secretary talking the dollar down, as the expression goes. I understand the impetus – it makes exports easier, which should help employment. But of course, you’re also being paid in depreciated dollars. Some Short History Reading Lists

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, Cold War, Constitution, History, Revolutionary War on January 21st, 2018

We were over at a friend’s house for lunch this Shabbat. Knowing that 1) I have a lot of history books, and 2) I tend to read them, he was kind enough to ask me for some reading lists about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Cold War. “I haven’t had much luck with fiction, so I’m trying to round out my history.”

Here’s what I sent him. These aren’t intended to be college syllabuses, or comprehensive. They’re books that I have and leafed through, or that I’ve read. I’ve tried to vary them by author. I could have had the entire Revolutionary War list by Joseph Ellis, the whole Civil War list by Bruce Catton, but what’s the fun in that? My library, while large by 19th Century standards, is limited by the size of the house. Had I fewer books, I would paradoxically have more room for them. But it’s a good list, enough to cover some key points, get an overview, or just when your appetite for more.

American Revolution

For a decent overview of the war as a whole, Liberty by Thomas Fleming isn’t bad. I think it was originally written as a companion book to a PBS series, but it’s good in its own right. For a deeper examination of the issues around the Revolution and the war, and how the Founders handled them, American Creation by Joseph Ellis is recommended.

We all know of Washington Crossing the Delaware; David Hackett Fischer has written a great in-depth review of the events surrounding that crossing and subsequent battles, and how they set the stage for the rest of the war, in Washington’s Crossing.

And for well-researched discussions of adoption of the two primary founding documents – the Declaration and the Constitution, Pauline Maier’s American Scripture and Ratification give surprising insights into what people were thinking at the time.

The Founders lived on into the post-Revolutionary era, and had a second act right after the Constitution in 1787, so some bios are in order. Richard Brookheiser’s short Founding Father is a fine thumbnail bio of Washington; for something longer Ron Chernow has bios of both Washington and Hamilton. And David McCullough’s John Adams is what the PBS series was based on.

Having come this far, read about 700+ pages about the early Republic, when were getting ourselves established, with Gordon Wood’s Empire of Liberty. I’m reading it now, and pretty much every chapter has some surprise or another.

Civil War

For the lead-up to the war, and how we got to the point of secession and war, William Freehling’s long, two-volume The Road to Disunion is among the best.

Much of the same material is covered in the first volume of Bruce Catton’s very readable and shorter three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War. These are The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat. I would recommend anything written by Catton on the Civil War.

Also excellent is Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson. As a guide to Lincoln’s war, what the events looked like from DC, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals is magnificent.

Cold War

This one is tougher, because it covers decades, not mere years, so the politics, military, and technology changed substantially from 1948 to 1989. I’ve picked out the books I have and have read that do a good job talking about the Cold War. My library is heavier on the spy stuff, but there was a lot of spy stuff.

Witness by Whittaker Chambers is indispensable. He starts out as a Communist, and then converts over to the good guys, and was a key player in one of the great Cold War controversies, the Alger Hiss case. Nixon’s rise to prominence began with this case, and the left never forgave him for being right.

The Great Terror, is one of the best books about Stalin’s Russia, by one of the best chroniclers of the 20th Century, Robert Conquest.

The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn is recognized as the best insider account of the Soviet punishment system.

Berlin 1961 by Frederick Kempe covers the building of the Berlin Wall.

Merchants of Treason by my friend Norman Polmar and KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents are old now, but a good guide to how to the KGB operated in the day, and how the Russians still operate today.

There’s also a vast literature of spy fiction, from Len Deighton’s devastating Game-Set-Match trilogy to John LeCarre’s oeuvre (start with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy).

That’s enough to keep you busy for a few years. So what are you still doing on this page?

DACA and the Courts

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Immigration, National Politics on January 11th, 2018

Two days ago, a 9th Circuit federal judge in San Francisco blocked the Trump Administration’s reversal of Obama’s DACA, the program under which illegal aliens brought here as children could register, in return for a suspension of enforcement of immigration law. He did so with a decision that, as Josh Blackman puts it, reads like bad punditry, bereft of any legal reasoning or precedent.

On the Twitters, the pseudonymous “Thomas H Crown” explains in an 800-word thread what got us here, why this sort of ruling both stems from and feeds a deeper civic rot.

So a judge begins with the proposition that an executive order is lawfully entered; executive orders by definition lie entirely in the discretion of the Executive and may be withdrawn or advanced at his sole discretion; and concluded withdrawing it may be illegal.

The problem with our system of government right now is diffuse responsibility and a categorical unwillingness by the legitimately-enumerated-and-responsible actors to retake their power and responsibility.

The judiciary has absolutely no power to order the Executive to retain a program the Executive created ex nihilo and contrary to the express terms of a lawfully-enacted, Constitutional statute.

The Executive should be aggrieved because its power is being summarily denied by a Branch with no rule/law-making power of its own; its power is (theoretically) limited to derivative lawmaking based on other Branches’ acts.

The Legislature should be absolutely losing its poop because (1) its power was wrongfully grabbed by the Executive at the start and (2) now that the Executive is backing down, the Judiciary is grabbing the mantle in its place.

Elementary civics teaches that the Constitution creates checks and balances, i.e., no one branch can become more powerful than any other because each has a power to negate the one taking its authority; and two beat one.

Elementary civics also teaches that Congress has the power, under extraordinary circumstances, to rip the other branches to shreds, by impeachment and by defunding their day-to-day operations (but not Article III’s salaries).

But this arrangement is a dead letter.

Instead, here, roughly, is our system.

Congress passes laws sometimes and sometimes not, and passes budgets sometimes and sometimes not, but never actually exercises the power of the purse over anything.

Impeachment, because of its uneven execution on the Executive, is considered a nuclear device, and even in the face of clear lawbreaking and arrogation of power is at best a toss of slightly-loaded dice.

The bulk of lawmaking is actually done by the Executive, by a facially unconstitutional delegation of authority of that power by Congress almost a century ago that most people now take for granted.

When the Executive makes laws/novel interpretations completely outside the text/creates whole new programs, Congress races to fundraise off it. Sometimes, it asks the third branch to say the second is naughty.

The judiciary makes new Constitutional amendments, something it’s really not qualified to do (lawyers know our own), occasionally orders the Executive to change its interpretation of a law to what the judiciary wants, and now runs illegal Executive programs.

Instead of ordering up a round of impeachments or at least informing the judiciary that its electric, gas, water, rent, etc., bills won’t be paid any more, Congress races to fundraise.

Instead of telling the judiciary it can enforce its own damned laws (BUT THE MARSHAL OF THE SUPREME COURT) if it wants to be the Executive, the Executive asks the judiciary to please reconsider. Please.

So instead of Article I — the first and most expansive — being primus inter pares, which is necessary for effective small-r republican governance, or Article II, which is at least elected, the system is totally inverted and no one changes it.

The system is now designed to funnel power to the only unelected — and therefore least-inclined to republican responsibility — branch, then the second-least responsible, and leave the most electorally-responsible one the one with the least power.

In times of economic downturn or uncertainty, direct stimulus to the humans does not lead to increased spending. They instead disproportionately use it to pay down debt or accrue savings (same thing).

This is because the humans are surprisingly cannier than the people they elect to govern them.

The effects are fairly straightforward: Increased voter apathy, lower turnout for elections in which only Congress is in play, and increased energy and commitment to the outcome of the only elected branch where real decisions are made.

In other words, the humans can tell that there’s no point in caring too too much about Congress, as it’s an ATM with occasional fits of lawmaking, and a great deal of reason to care about the Executive, the source (more or less) of judges and only meaningful elected office.

It’s an unpleasant feedback loop, as this only encourages the same mess that caused that behavior in the first place.

Worse, the incentives the Founders identified in the elected officials were way and totally wrong. In Congress, they don’t care about power, they care about prestige, the appearance of power, and wealth.

They have no incentive to check the Executive or Judiciary because if what they do doesn’t make vox populi roar with approval, their incentives could be endangered.

The people care that they feel like they have a responsive system, regardless of the accuracy of this feeling, and have a king/champion and wise philosopher bench to guide them.

If you care about republican governance, this is a truly hideous state of affairs.

Most people don’t.

People have been fixated on the dangers of getting used to Trump’s unusual behavior for a president. Getting used to this kind of “because I said so” jurisprudence strikes me as just as dangerous. Hamilton wrote that the judiciary would be the weakest branch, and that judges would be afraid of getting so far out of line for fear of being impeached. This is the kind of ruling that begins to make impeachment look plausible.

PERA Forum

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on January 10th, 2018

On December 20th of last year, the South Metro Denver Chamber of Commerce hosted a forum on the future of Colorado’s deeply troubled public pensions, the Public Employees Retirement Association, or PERA.

PERA’s been in trouble for a while, but it only noticed how much trouble it was in late in 2016 when it adopted new mortality tables an a slightly less unrealistic estimate of its long-term rate of return. Since then, it’s been frantically trying to salvage the current defined benefit plan. PERA has a legislative proposal to tighten up COLAs, slightly increase the retirement age, increase contributions, and tighten up some loopholes in the benefit calculation formula. Governor Hickenlooper has released a plan of his own, similar to PERA’s with a few tweaks.

Independence Institute and I think the long-term solution needs to be more sweeping – a cutoff of the traditional pension plan for new members, and even providing the option for existing members to transfer into a new, 401(k)-style defined contribution plan. This won’t get rid of the massive, $80 billion unfunded liability, but it will keep it from getting any worse, and it will take the investment risk off the shoulders of the rest of the state and put it where it belongs, on the shoulders of the employees themselves.

The panel featured PERA’s interim Executive Direction Ron Baker, Amy Slothower representing the pro-reform Secure Futures Colorado, and Lynnea Hansen of the pro-PERA Secure PERA lobbying group, and me. It was moderated by State Senator Jack Tate (R-Arapahoe).

Here’s the audio from the event:

As you can see, things got most heated around the discussion of the composition and responsibilities of PERA’s Board of Trustees. Ron claimed the PERA’s Board was responsible for managing the money and administering the plan. That’s true, but as I point out, it’s far too modest. PERA’s Board also lobbies the legislature, posing as a disinterested unbiased source of information, but in fact opposing almost all interim reform proposals, including some that are now part of its proposed slate of reforms.

The Eternal Tax Debate – Lessons from the 1920s

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Economics, History, Taxes on November 28th, 2017

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

Growth was too low, as the post-war economy struggled to recover from a recession.

The new president and his treasury secretary were convinced that a serious package of tax reform could unleash much-needed growth.

And they had a plan. The top marginal rate was too high; it should be in the 20s. The estate tax drove down the price of assets and should be eliminated. There were too many special carve-outs. Tax-free interest on municipal bonds was diverting capital from private enterprise.

To be sure, not all the proposals were for lowering tax rates. The secretary wanted a capital gains rate higher than the income tax rate.

But the political situation was working against them. Their own party was split, and they ran into opposition not just from the openly Progressive party, but from the Progressive wing of their own party, which included the Senate Majority Leader. Opponents of the administration’s plans pointed out that the bulk of the benefits would go to the wealthy, including the treasury secretary himself.

Opponents argued that federal revenue would plunge; the treasury secretary persuaded the president that unlocking capital would cause an economic boom and swell the tax take. They argued for a top tax rate around 40%.

Conservatives believed that nearly everyone should pay something. Progressives disagreed.

Scandals, distractions, and Congressional investigations also sapped the president’s attention and political capital.

The president and the treasury secretary also complained that the time it was taking to pass a bill was extending the experimentation of the previous Democratic administration, and the destructive uncertainty that accompanied it. Passing something, they argued, even if it didn’t meet their exact specifications, would be more important than dithering and passing nothing.

Eventually, the treasury secretary would get his tax reform package, mostly on his own terms, and he and the president would see federal revenue leap upward as a result. (He wouldn’t get everything; the secretary wanted a top marginal tax rate in the 20s; Congress seemed more inclined to something around 40%.)

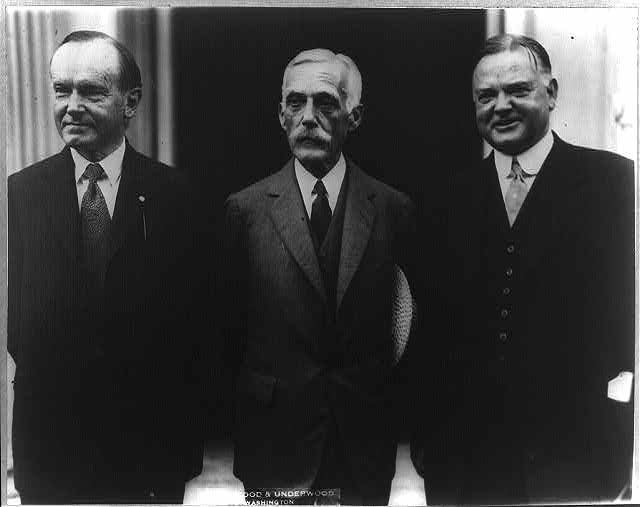

The treasury secretary was Andrew Mellon, and it would take another round of elections, the death of President Harding and the accession of President Coolidge to make it happen.

Ironically, these tax reform plans weren’t originally even Mellon’s. Wilson Administration Treasury Department bureaucrats developed them after the war. They hoped to transform federal tax policy from an ad hoc patchwork into a permanent, systemic tax regime, the emphasis being on permanent.

Ninety years later, we are still having substantially the same discussions, on substantially the same terms. Does that mean that the Progressives were successful? Perhaps, and perhaps not.

Mellon dubbed his approach “scientific taxation,” designed to maximize revenue while minimizing the tax burden. But the fact that we’re still picking over many of the same details in 2017 suggests that the science is far from settled.

Analogies to past epochs in American history are not currently commonplace. Some see a darker replay of the late 60s and early 70s. Others, more alarmist, see a replay of the pre-Civil War 1850s divide. Those comparisons rely more on the social atmosphere than on specific issues.

It’s unusual to see a policy debate stagnating, with the same arguments, over roughly the same issues, for nearly a century.

To some degree, this is the peculiar result of its being both narrow and central. The income tax itself cuts across numerous persistent philosophical and political divides.

Superficially, the room for policy debate is narrow: after 100 years, the personal income tax’s basic structure – progressive rates with special-interest credits and deductions – remains essentially the same.

But the tax’s seeming simplicity masks endless room for mischief, and therein lie the complications.

The personal income tax contributes nearly half of the federal government’s annual revenue; combine it with the payroll tax, and just under 5/6 of federal tax revenue is based off of personal income.

Lowering or raising rates will affect not only an individual year’s deficit, but also the economy’s rate of growth and attendant opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, and employment. The overall take calls into question the size of government as a whole.

The amount of progressiveness, both the top rate and the number of people who pay nothing, raise the ill-defined but politically potent question of “fairness.”

In policy terms, each deduction or credit raises the question of whether or not the government should be supporting or suppressing the industry or choice involved. What gets exempted raises the question of privileged institutions like university endowments or state and municipal debt and taxes.

In fact, the whole structure implicitly accepts the idea that it’s the federal government’s job to support or suppress certain economic decisions. That credits and deductions can only be taken under certain circumstances open the door to micromanaging those decisions.

And every one of these credits and deductions immediately acquires a non-partisan, which is to say bipartisan, constituency, either because it helps someone or hurts their competition. Thus are we treated to the spectacle of otherwise conservative Republicans in New York, California, and New Jersey defending national taxpayer subsidies for their expansive state and local governments.

That goes a long way toward explaining why we’re stuck in the same debate.

And unfortunately, why we probably will be for a long time.

PERA and the 30-Year Amortization

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on October 25th, 2017

In its campaign to sell its proposed reforms the PERA board has taken to emphasizing that the 30-year amortization period is written into Colorado statute. Per C.R.S. 24-51-211:

(1) An amortization period for each of the state division, school division, local government division, judicial division, and Denver public schools division trust funds shall be calculated separately. A maximum amortization period of thirty years shall be deemed actuarially sound. Upon recommendation of the board, and with the advice of the actuary, the employer or member contribution rates for the plan may be adjusted by the general assembly when indicated by actuarial experience.

Not only did they mention this at the Aurora tour stop last week, they tweeted it out last night.

The less rigorous standard means they never actually have to achieve full funding. PERA’s appeal to the authority of the law in this case rings hollow.

It’s the industry standard for public pensions, which is why it was written into the law in the first place. Presumably, if the industry standard were to change, the statute would change as well. Legislators aren’t experts in this material; they were clearly relying on the recommendations of the public pension stewards at the time. In effect, PERA is appealing to its own authority in this matter.

The fact is, industry standards for public pensions haven’t saved the industry from its problems. Not so long ago, the industry standard was a rate of return well over 8%. Right after SB1 was implements, PERA’ amortization periods all dropped under 30 years. That lasted all of one year.

The choice of a target amortization period should be based on whether or not it makes sense, not on appeals to authority that have proven less than authoritative over the years.

Photo Credit: Todd Shepherd

Breaking News from 1800

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on October 23rd, 2017

In 1800, in the midst of a contentious presidential election, Alexander Hamilton decided that the future of the Federalist Party was too important to be left in the hands of John Adams. In order to promote his own candidate for Federalist electoral votes, Hamilton issued an anti-Adams broadside cataloging the shortcomings of Adams as president. Chernow assesses the screed as one of the worst of Hamilton’s political miscalculations.

That it was partly also driven by personal grievances, though, doesn’t change the truth of some of the charges, or that they echoed much of the popular sentiment around Adams’s performance in the job. Many of the weaknesses of the Adams presidency may sound familiar to observers in 2017, even though the book was written in 2004.

Beyond the unenviable task of succeeding Washington, Adams had several handicaps to overcome. Despite long years in politics, he had never exercised executive power at the state or federal level. And he detested political parties at a time when America was being torn asunder by factions. As president, Adams was the nominal head of the Federalists, but yet he dreamed of being a nonpartisan president….During his presidency, Adams was often stranded between the Federalists and the Republicans and accepted by neither. It was to prove a rare case in American history of the president hesitating to function as the de facto party leader. — p. 523

He had retained his cabinet from the second Washington Administration. But even as he found himself frequently publicly at war with them, he refused to fire them until late in his term. It was certainly true that Hamilton exercised some influence over the individual cabinet members, in some part because he bothered to engage them rather than dictate to them from afar during his frequent absences in Quincy.

Washington had always shown great care and humility in soliciting the views of his cabinet. Adams, in contrast, often disregarded his cabinet and enlisted friends and family, especially Abigail, as trusted advisers. His cabinet members found him aloof and capricious and prone to bark out orders instead of asking opinions. — p.524

Adams, having held over for too long subordinates with no personal loyalty to him, or ideological loyalty to his program, whatever than might have been, found himself stuck with no good defense of his leadership, and so found himself putting out several mutually inconsistent but self-serving versions, simultaneous arguing that people were working to undermine him, and that he was actually in control and playing a higher-level game the whole time:

John Adams told two stories of his presidency that never quite jibed. In one, he claimed to be an innocent bystander, long oblivious of Hamilton’s influence over his cabinet members. He had no idea until the end, he said, that they were receiving guidance from his foe; when he belatedly discovered the plot, he moved swiftly to purge the culprits. In another version, Adams claimed that he had known all along that Hamilton controlled the cabinet, because he had already controlled it under Washington… — p. 524

And Hamilton’s pamphlet drew heavily on anonymous, inside sources – the cabinet members themselves – who were concerned about Adams’s temperament and suitability for the job.

[Treasury Secretary Oliver] Woolcott considered the president a powder keg. Of Adams, he told Fisher Ames, “We know the temper of his mind to be revolutionary, violent and vinditive…. [H]is passions and selfishness would continually gain strength.” …At moments, however, Woolcott grew ambivalent about the idea of Hamilton exposing Adams, arguing that, “the people [already] believe that their president is crazy.”

Thus, in his massive indictment of Adams, Hamilton drew on abundant information provided by McHenry, Pickering, and Woolcott about presidential behavior behind closed doors….Stories about Adams’s high-strung behavior, if legion in High Federalist circles, were little known outside of them. Hamilton also wanted to stress the mistreatment of cabinet members, lest readers dismiss his critique of Adams as mere personal pique…

Yes, the Republic survived both the mutual enmity of protean political parties, and the chaotic behavior of the often-absentee Adams. But that was at the beginning of our Constitutional framework, when we were still working out how the presidency and parties would work. (And even then, one could argue that parties didn’t survive this first attempt. The Federalists pretty much collapsed after the 1800 election, leaving no effective opposition to Jefferson’s Republicans. Madison was widely blamed for a terribly destructive and unpopular War of 1812, but the mediocrity that was James Monroe won two terms virtually unopposed, anyway.)

The point is that by now, we’re a world power, still the wealthiest nation on earth, responsible for maintaining freedom of the seas and some level of global stability. That we’ve reverted back to some of the inchoate quality of our early political development does not necessarily bode well for the coming decades, possibly the coming century.