Lincoln, Labor, and Us

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on September 7th, 2020

On March 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln spoke at New Haven, Connecticut. It was part of the same speaking tour that had taken him to Cooper Institute in New York City, but coming after that speech, in a smaller venue, it has attracted much less historical attention.

No doubt it also attracts less attention now is that much of the speech is a rehash of ideas first presented in the Cooper Institute speech. One section, however, discusses a “shoe strike” then going on in New England, and it thus particularly appropriate for Labor Day.

Workers in shoe manufacturing plants had first struck in Massachusetts over wages. Even though there was no formal union, the strike spread to other plants across New England. Lincoln, in the manner of politicians everywhere, sought to address great national issues in the context of local ones., in this case, slavery.

I am merely going to speculate a little about some of its phases. And at the outset, I am glad to see that a system of labor prevails in New England under which laborers CAN strike when they want to where they are not obliged to work under all circumstances, and are not tied down and obliged to labor whether you pay them or not! I like the system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere. One of the reasons why I am opposed to Slavery is just here.

So far, Lincoln is making a fairly pragmatic pro-free labor argument, one that will resonate with northern workers: that they have the right to quit and deprive the boss of their labor whenever they feel like it. He goes on:

When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition —when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!

Now, Lincoln moves subtly to a natural rights argument, one that goes straight after some Southerners’ argument that black men aren’t really human. Not only are blacks human, but they are also entitled to the same human rights as everyone else when it comes to selling their labor and improving their condition. Even to the point of being able to hire other men to work.

The outcome of this freedom is a general prosperity where wealth is no longer directly tied to the soil, while hinting at the next direction he’s taking this argument:

That is the true system. Up here in New England, you have a soil that scarcely sprouts black-eyed beans, and yet where will you find wealthy men so wealthy, and poverty so rarely in extremity? There is not another such place on earth! I desire that if you get too thick here, and find it hard to better your condition on this soil, you may have a chance to strike and go somewhere else, where you may not be degraded, nor have your family corrupted by forced rivalry with negro slaves.

Then comes the direct attack on Stephen Douglas, several paragraphs long, which require some unpacking. They refer to other events and even to other arguments that Lincoln was making, which the audience at the time would have understood. We might not grasp them at first, but once we do, the ominous similarities to today’s politics will be clear.

Now, to come back to this shoe strike,—if, as the Senator from Illinois asserts, this is caused by withdrawal of Southern votes, consider briefly how you will meet the difficulty. You have done nothing, and have protested that you have done nothing, to injure the South. And yet, to get back the shoe trade, you must leave off doing something that you are now doing. What is it? You must stop thinking slavery wrong! Let your institutions be wholly changed; let your State Constitutions be subverted, glorify slavery, and so you will get back the shoe trade—for what? You have brought owned labor with it to compete with your own labor, to under work you, and to degrade you! Are you ready to get back the trade on those terms?

But the statement is not correct. You have not lost that trade; orders were never better than now! Senator Mason, a Democrat, comes into the Senate in homespun, a proof that the dissolution of the Union has actually begun! but orders are the same. Your factories have not struck work, neither those where they make anything for coats, nor for pants, nor for shirts, nor for ladies’ dresses. Mr. Mason has not reached the manufacturers who ought to have made him a coat and pants! To make his proof good for anything he should have come into the Senate barefoot!

Recall that in the Cooper Institute address, Lincoln says that the South will never be mollified as long as the North continues to believe that slavery is wrong. Only a change in Northern beliefs – to be signalled by censorship of anti-slavery speech and changes in northern laws – will persuade the South that the North means slavery no harm where it exists.

Lincoln here is showing what that would look like. The Dred Scott decision has already brought the country close to the point where free soil laws might be illegal, that slaves brought by a southerner into a free state do not automatically become free. The next logical step would be to force the free states to permit not merely personal servants but slave labor in commercial enterprises.

Lincoln is also contradicting a frequently-assumed argument for popular sovereignty, that slavery simply won’t work in certain places. Part of the argument in favor of popular sovereignty was that if people didn’t want slavery, or if the climate of a place wouldn’t support it, then it wouldn’t take root no matter what the laws were. Lincoln appears to be arguing contrary to this, saying that slavery could well exist in an industrial economy, and that therefore laws against it are necessary.

This is an unsettled point among historians. Harry Jaffa seems to agree that slavery wouldn’t have worked in California or the New Mexico territory in Crisis of The House Divided. In his book The Impending Crisis, David Potter argues that Jaffa doesn’t quite prove the point, and re-opens the question about what would have happened had slavery not been banned in certain areas. Lincoln appears to be taking Potter’s position here, that slavery might well be possible no matter what the economy.

There was also, at this time, a movement in the South to boycott northern goods over the north’s opposition to slavery. So Lincoln is mocking that boycott as ineffective, and nothing to be afraid of.

Another bushwhacking contrivance; simply that, nothing else! I find a good many people who are very much concerned about the loss of Southern trade. Now either these people are sincere or they are not. I will speculate a little about that. If they are sincere, and are moved by any real danger of the loss of Southern trade, they will simply get their names on the white list, and then, instead of persuading Republicans to do likewise, they will be glad to keep you away! Don’t you see they thus shut off competition? They would not be whispering around to Republicans to come in and share the profits with them. But if they are not sincere, and are merely trying to fool Republicans out of their votes, they will grow very anxious about your pecuniary prospects; they are afraid you are going to get broken up and ruined; they did not care about Democratic votes—Oh no, no, no! You must judge which class those belong to whom you meet; I leave it to you to determine from the facts.

Here, Lincoln (to laughter) isn’t merely mocking the boycott – he’s pointing out its partisan nature. Northern Democratic businessmen were trying to organize a “white list,” (not in the racial sense, but as the opposite of a “blacklist” from which Southerners would not buy). Southern Democrats could then buy from Northern Democrats.

And your Democrat neighbors aren’t concerned about your profits because they’re not really worried about the boycott – if they were, they could just get themselves whitelisted and take your business. No, they’re worried about your votes.

All of this sounds dismayingly familiar – partisan boycotts, pretend concern for political opponents’ well-being, and demands that the other side not merely behave a certain way, but believe a certain way.

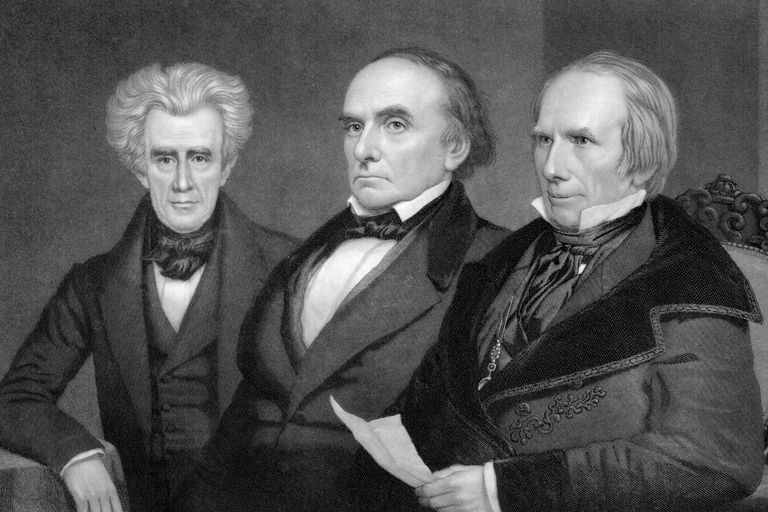

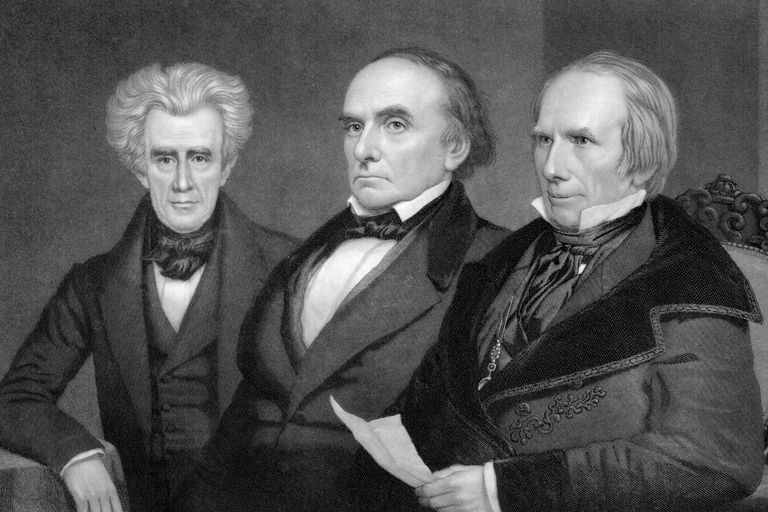

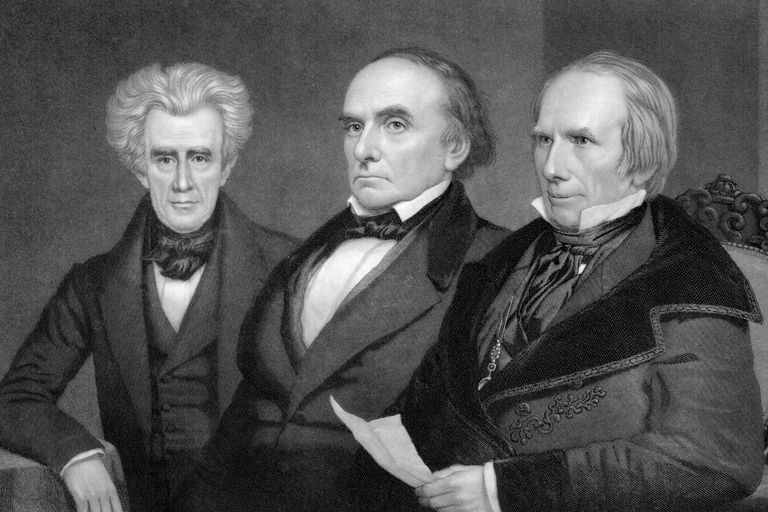

The Great Triumvirate, Summarized

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 10th, 2018

Tonight was our book club meeting for The Great Triumvirate, Merrill Peterson’s seminal history of the second generation of American political leadership – Clay, Webster, and Calhoun.

Tonight was our book club meeting for The Great Triumvirate, Merrill Peterson’s seminal history of the second generation of American political leadership – Clay, Webster, and Calhoun.

In discussing the differences among the three, and summing up, a point occurred to me that I hadn’t thought of until I offered it to the group: each man’s greatest strength represented a singular aspect of statesmanship.

Clay was the consummate legislator, putting together a comprehensive program of action, and adhering to the principle that politics is the art of compromising without being compromised. He was a bit of a peacock, but he also did the hard work of figuring out where there was common ground, allowing people to give without betraying their principles.

Perfect for a legislator, but perhaps not so much for an executive, and country might well be better off that Clay never became president. As secretary of state, he hated the drudgery of paperwork and administrative work. And while he defined the pragmatic vision of the Whigs, he made the party over so much in his image that it didn’t long survive his death.

Webster was the great rhetorician, able to encapsulate an argument or an idea in a monumental speech. To him belong three of the greatest speeches of the 19th Century – the Plymouth Oration, the Bunker Hill Monument, and the Second Reply to Hayne. None of the main ideas is original, but each cemented in the public mind core principles of the republic.

And yet, for all his rhetorical brilliance, Webster was always going to be a follower, never the leader of either the Federalists or the Whigs. Of the three, he might have made the best president. As secretary of state, he made efficient use of his executive power. But because he could never lead his party, he would never even so much as sniff a nomination.

Calhoun was the theoretician, constructing a philosophical system to defend the south, its way of life, and of course, slavery. His great image of the Union as a contract among sovereign states rather than a covenant among free people would prove flexible enough to let him manipulate the Senate for decades, usually in opposition.

But in its service, Calhoun proved bafflingly flexible himself, finding principles convenient to the debate of the moment that he believed could fit in his overall philosophical framework. This let him maintain an iron grip on South Carolina politics, and eventually endeared him to much of the South, but in his lifetime, it left him isolated. Without a party or national vision, it’s hard to see how he could have governed as president.

Of course, these were only strengths, not the sum total of their political skills. Clay could speak. and buried in his American system was a philosophy of government. Webster understood ideas as well as anyone, and could compromise to get bills passed. And Calhoun’s rhetoric was sharp, if unimaginative, and he knew how to frame issues to draw distinctions and gain allies.

Still, the life’s work and achievements of each would be defined by their typical working styles – Clay the pragmatist; Webster the speaker, and Calhoun the thinker.

The Deep State, “Credible” Allegations: The Devil and Daniel Webster

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 23rd, 2018

The Devil, in this case, being politics as we know it today, practiced yesterday.

In 1842, Daniel Webster was John Tyler’s Secretary of State. Among the issues he had to deal with was a lingering dispute – since the Revolutionary War – between the US and Britain over the border between Maine and Canada. One obstacle to a settlement was the maximalist demands of Maine itself, whose senators would be voting on the treaty, and whose people would have to be relied on not to make trouble by trying to settle territory ceded to Britain and precipitating a war.

Parallel to the negotiations, Webster helped arrange for federal funds to secretly underwrite a public relations campaign in Maine in support of the proposed settlement. The treaty was eventually approved by the Senate by a vote of 39-9.

However, later, in 1846, Charles Jared Ingersoll, a Democratic congressman from Philadelphia, went on a tirade in the House against the treaty. He was particularly incensed that Webster had settled the Maine boundary without also settling the Oregon boundary. He also revived some old charges from years before. Webster, back in the Senate and rising to the bait, fired back ferociously. “He was not known for his invective, but here, it was reported, the invective exceeded that of Cicero, Burke, and Sheridan, to say nothing of Randolph, Clay, and Benton.”

Ingersoll figured he had hit a nerve.

“Where there was so much wrath, there must be guilt, so he now pursued his investigation into the State Department. There he discovered the expenditures from the secret service fund [this is not the Secret Service we know today, founded in 1865 -ed.]. Returning to the House, he charged Webster with misappropriation of funds and corruption of the press, and demanded an investigation. The refusal of President James K. Polk to break the seal of secrecy on the contingency fund, combined with Tyler’s testimony defending Webster and assuming full responsibility for the expenditures, doomed the project.”

It doomed Ingersoll, but in fact, Webster had been using clandestine taxpayer funds to run a domestic PR campaign in support of a treaty he negotiated. This may not rise quite to the level of leaking information to the press in order to use press stories to obtain surveillance warrants, but it is kinda of deep-statish.

Back in 1842, Webster was fighting off another kind of allegation all too familiar.

“In January 1842, George Prentice had published in the Louisville Daily Journal an editorial, ‘Anecdote of Daniel Webster,’ that gave a lurid account of [Webster’s] seduction of the wife of a poor clerk in his department. She had come to him asking employment as a secretary. After sending her to an adjoining room to provide a specimen of her handwriting, Webster came in, closed the door, and pounced on her… She screamed and clerks rushed in, thus forestalling ‘the old debauchee.’ Affidavits from Washington, one of them filed by Webster himself with a local magistrate, forced Prentice to retract the story…”

The story never found any real audience then or now, and he always blamed Clay for having planted it. But the fact that he was forced to deny it seemed to stain him all by itself.

Plus ça change.

Operation Finale

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Movies on September 23rd, 2018

“Our memory reaches back through recorded history. The book of memory still lies open. And you here now are the hand that holds the pen.

“If you succeed, for the first time in our history we will judge our executioner.”

With these words, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion sends the special Mossad unit off on its mission to Buenos Aires, to capture the Architect of the Final Solution and retrieve him to Israel to face justice, or at least as much justice as this world has to offer. It is an arresting, energizing moment in Operation Finale, Oscar Isaac’s film treatment of one of the Mossad’s early high-profile successes, and a defining moment itself in Jewish history.

The quote is especially apt, as much of the criticism of the movie revolves, wittingly or not, around the distinction between history and memory, and blurring that distinction in the name of art and commerce. Some of these compromises are valid. Others are unfortunate because unnecessary; the real operation had plenty of tension in real life.

There are more recent accounts, but Isser Harel’s The House on Garibaldi Street still captures most of the key operational details, as well as its flavor and atmosphere. In it, the then-head of the Mossad recounts the tip that led to the investigation, as well as the operational difficulties of working in a country far from home with a language barrier. Harel, for instance, ran the operation from diners, on a rotation known to the operatives, where they would meet and pass messages. The movie shows this briefly, but misses an amusing and potentially fatal error – the cafes that Harel had a “back room,” but by Argentinian custom, that room was almost exclusively used by women, making him stand out like a sore thumb and forcing a change in technique.

Also amusing was the difficulty that the team had in obtaining reliable transportation. Car after car broke down or had tire problems, or some other mechanical issue. They couldn’t rent or buy an expensive car for fear of attracting attention, so they were stuck with a series of lemons that might fail them at any moment, up to and including the decisive drive to the airport. Instead, we just see a lot of greenbacks changing hands for a couple of local cars.

There were multiple safe houses, with compromises made in choosing each one. There were questions about the safety of the route to the airport, and the possibility of using a shipping container was discussed, but during the operation as a backup, not in the initial planning as shown. And there was considerable concern about the diplomatic fallout with Argentina, all of which was justified by later events.

Isaac chooses to forego all of this real-life drama for what amount to three major historical compromises. First, El Al, which loaned the plane to Mossad, didn’t require a signed statement by Eichmann that he was going of his own free will. Second, there was no last-minute frenzied escape at the airport, hotly pursued by Nazi-infested Argentine police. Third, and related Graciela Sirota was not tortured in an effort to discover their location. To varying degrees, these historical compromises serve memory. They also, to varying degrees, do a disservice to the movie.

The conceit that El Al required Eichmann to sign a statement in order to permit the Mossad to transport him sets up an interrogation thread after Eichmann’s capture and removal to the safe house. Strictly historically, the Israelis who were charged with babysitting Eichmann did suffer psychologically from having to deal with him, and did end up slowly bending the strict minimum-contact rules that were initially imposed. Those were the result of 10 days in close contact, not a need to extract a statement. But the narrative thread serves another purpose, essentially moving Eichmann’s eventual defense from the trial into the safe house. To that extent, it’s perfectly good filmmaking. The memory of what Eichmann claimed remains the same, the story line is just compressed.

The other two compromises – offshoots of one invention, actually – are less defensible. The Israelis expected that Eichmann’s family would be loath to go to the police with a missing persons complaint, precisely because his presence in Argentina was under an assumed name. Giving a plausible reason for his kidnapping would mean blowing his cover. But it also means that while there was a surreptitious low-level search, there were none of the resources available that a full police investigation would have had. No close calls with people staring in windows, no mad dash to the airport after a hair-breadth escape, no police chasing down the airplane as it took off. This is pure cinematic dramatic invention, when drama would have been better-served by honing in on the operational issues.

The last incident – the torture of Graciela Sirota – happened, but the movie places it in the context of the chase. In fact, Miss Sirota was tortured and left with a swastika tattoo in June 1962, after Eichmann’s execution. It was part of a larger antisemitic backlash against the local Jewish community, and both its occurrence and the police indifference to it prompted a broad reaction in Argentinian society, isolating the antisemitic elements, and forcing the government to take action against the groups responsible. This is all chronicled in “The Eichmann Kidnapping: Its Effects on Argentine-Israeli Relations and the Local Jewish Community,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 7, No., 3, Spring-Summer 2001. So in this case, even the memory is somewhat garbled.

If the reader has made it this far, he probably thinks I didn’t much like the film, but I did. The character development is first-rate. The head-butting between Eichmann and Oscar Issac’s Malkin fulfills Israel’s promise to let Eichmann have his say. For those who don’t know better, one form of suspense about the outcome is as good as another. So the movie is good, as a movie. In its important parts, it’s even pretty good as memory. But it could have been better at both those things, and still better as history.

The Great Triumvirate

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on September 20th, 2018

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

I’m continuing to work through Merrill Peterson’s The Great Triumvirate, about Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. These three legislative titans dominated Congress during a period of Congressional dominance from the 1820s through the 1840s. We normally think of this as the Age of Jackson, and most histories revolve around the key presidents of the period – Jackson and Polk, and to some degree the accidental John Tyler. Peterson’s genius is to recognize both the relative legislative control compared our age, and to examine both politics and policy through the shifting relationships among these three giants.

Since it’s 2018, and not 1838, things differ. But pretty much every reading of American history is a lesson in how our own political dynamics have deep roots.

For instance, our political system is, as one wag put it, “ridiculously over-designed” when it comes to distributing political power. We not only have federalism, which limits the national government and reserves most policy-making to the states. We also have, at every level of government, separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. These structures were so over-designed that it has taken a couple of centuries and the trojan-horsing of late 19th Century European political ideas inside our walls to break down these barriers.

Given the proximity to the Founding – the creation of the Constitution was still a living memory into this period, one might therefore think that one party would be dedicated to a concentration of power, and one party dedicated to a distribution of power as the Founders intended. That roughly, although not perfectly, mirrors the situation today.

But in the Clay Whig vs. Jackson Democrat era, it didn’t. The Whigs sought broader federal powers, especially as regards internal improvements and protectionist tariffs, but legislative supremacy at the federal level and vigorous westward expansion. The Democrats wanted to devolve federal power and money back to the states, but concentrate federal power in the executive. In other words, each sought to adhere strictly to certain aspect of the Constitutional distribution of powers, while stretching others to achieve its desired political ends. (It goes without saying that neither had yet conceived of the bureaucratic state as a means of immunizing their policy preferences from popular opinion.)

The Jacksonians saw themselves as the logical extension of the “Spirit of ’98” and the Jeffersonian revolution of 1800, which is why, up until the current history purge, Democrats called their annual county dinners “Jefferson-Jackson Day” dinners.

Webster, never the leader of the Whigs but their most active campaigner in 1840, sought to turn the tables on them, relishing “beating the Democrats at their own game.” He campaigned on the idea that returning power to the legislature was fulfilling the Jeffersonian idea. The Democrats were appalled at his claim, but given the deep economic depression in 1840, nothing they said was likely to make much of an impression on the voting public.

From 70 to 2018

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Jewish, National Politics on July 20th, 2018

Sunday is the 9th of Av* on the Jewish Calendar. If Yom Kippur is universally recognized as the holiest day of the year, the 9th of Av, is unquestionably the saddest. It is the anniversary of the destruction of both the First and Second Temples. Jews around the world will mourn by fasting, reading the Book of Lamentations, and engaging in communal self-examination.

Self-examination for what, exactly? The Rabbis say that the Second Temple was destroyed as punishment for sinat chinam, among Jews, usually translated as “baseless hatred.”

But is any hatred truly baseless? Doesn’t even irrational hatred have some basis? Does anyone really hate someone else for no reason at all? Individuals have grudges, groups have rivalries, parties have different visions for the future. Sure, some of these may get out of hand, but are they ever totally baseless?

Rabbi David Fohrman discusses this at some length in his writing. In discussing the destruction of the Temple, the rabbis tell a story about what got the ball rolling. It’s the story of Kamsa and Bar Kamsa, and in it lies both the answer to our question, and a lesson for Americans today.

The story begins with a party. A wealthy man – he remains unnamed, perhaps a personal punishment – is throwing a party, and he sends his servant with an invitation to his friend, Kamsa. The servant, by mistake, brings the invitation to his enemy, a man named Bar Kamsa.

When the host sees Bar Kamsa at the party, he orders him to leave. Bar Kamsa, embarrassed at the mistake, asks to be allowed to save face. He’ll pay for his food. The host turns him down. He’ll pay for half the party. No, says the host, you must leave. Bar Kamsa will pay for the whole party, just don’t humiliate him in front all these people. No, insists the host, and forcibly escorts Bar Kamsa to the door.

What really stings Bar Kamsa, is that a number of prominent rabbis at the party saw the whole thing and who did nothing. Fine, the host was his enemy, thinks Bar Kamsa, I get that. He was being a jerk, but did I really expect anything better?

But the rabbis, it’s their job to encourage people to act with decency and respect, and they just sat there and did nothing. The longer Bar Kamsa thinks of this, the angrier he gets, until he finally decides to take revenge. He tells the Romans that the rabbis are plotting rebellion, manipulates events to make it look that way, and the whole thing snowballs into an actual revolt and the burning of the Temple. Bar Kamsa’s hatred has sown the seeds of Israel’s national destruction.

Fohrman notes that when we’ve been wronged, we react on two separate scales. One is how right we are, the other is how intensely we feel it. Was Bar Kamsa right? Of course he was. He humiliated in front of the cream of Jerusalem society, and the conscience of that society passively let it happen.

But on a scale of 1 to 10, how angry was he? Looks like 11. How angry should he have been? A four, maybe a five? After all, it’s just a party. By next week, everyone will have forgotten about it. Instead he decided to turn it into an international incident that ended up destroying the remnants of Jewish sovereignty for the next 1900 years.

Bar Kamsa, the host, and even to some extent the rabbis, had stopped seeing other people as whole human beings, and instead saw them as symbols. The host saw Bar Kamsa not as a person who was trying to redeem an uncomfortable situation, but as “enemy.” Bar Kamsa saw the rabbis as people who may not even have fully understood what was going on, but purely as instruments of his humiliation. The rabbis, for their part, didn’t see the host and Bar Kamsa as people acting out a personal drama in public, but as litigants in a dispute they couldn’t rule on. It’s much easier to get uncontrollably angry at a symbol than at an actual person.

Which brings us to today. Our social media personas can’t possibly reflect our full selves, and we react to others’ personas as though they were pure, true, authentic, and complete. For most of us, even for public figures, politics is a fragment of our lives. But we increasingly reduce each other to avatars of political movements, judging and punishing each other on that basis.

We react rather than taking time to think. We post with the fierce urgency of now, rather than the calm reflection of later. We use words designed for anger, and then find ourselves made angry not only by our own words, but by those of others. We go to 11 on the outrage meter and stay there, on everything, and we quickly make our disagreements about each other rather than about the thing we disagree on.

Increasingly, we think there is no escape, feel backed into a corner, raising the stakes of our politics. Each side believes that the other, given power, will use that power to take away our livelihoods and ruin our social lives merely for holding the “wrong” opinions. Each side believes that the other represents a metaphorical authoritarian gun pointed at our heads. Elected officials openly compare policy to the Holocaust, and call for the public harassment of political opponents – and it won’t end with high-level officials.

Since the election, the bulk of the hysteria has come from the Democrats and the Left. This is because they lost. However, given the reason that many voted for Trump, exemplified by Michael Anton’s famously persuasive Flight 93 Election article, I am reluctant to conclude that Republicans would have behaved much better had they lost. The Russians on whom so much attention is focused were careful to leave plenty of conspiratorial breadcrumbs on both sides of the street.

The Left is more responsible for the relentless politicization of every square inch of our public, private, and personal lives. But that doesn’t absolve anyone of trying to arrest this slide. Because we have a very clear message on the consequences of not arresting it.

And I have no idea how to put that back together.

*It’s actually the 10th of Av, but the fast and commemoration are put off for a day because the 9th falls on the Jewish Sabbath.

More From the Democratic Bad Idea Factory

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics on April 10th, 2018

Back in the 1960s, Colorado lengthened its state legislative session from 120 calendar days to 160, reverting it back to 120 via a 1988 Constitutional Amendment. It’s still among the longest in the country, and two Democratic bills up in the State House of Representatives argue in favor of reducing it even further.

Back in the 1960s, Colorado lengthened its state legislative session from 120 calendar days to 160, reverting it back to 120 via a 1988 Constitutional Amendment. It’s still among the longest in the country, and two Democratic bills up in the State House of Representatives argue in favor of reducing it even further.

The first, HB18-1209, would prevent parents and grandparents from using 529 accounts to deduct the cost of K-12 private school tuition from their state income taxes. Under 529 accounts, parents and grandparents may pre-fund college tuition tax-free. The 2017 tax reform law extended that exemption to K-12 education under federal law, but it remained up to the individual states to decide whether 529 deposits would be tax-exempt under state taxes.

In this session, two competing an diametrically opposed bills were introduced in the House. HB18-1221 (sponsored by Republicans) would have explicitly allowed 529 funds to be used to K-12 tax free, but it was killed in committee. HB18-1209, which is still alive, would explicitly prevent 529s from being used that way under state law. It will probably pass the House, and it’ll be up to the Republican-controlled Senate to kill it in committee.

The objections to HB18-1221 were primarily from the teachers unions and their supporters. They argued that it was an attack on public education, but to be honest, you can’t really get there from here. The money would have been deductible from the general fund. It’s not a voucher, it’s not even a refundable tax credit. It would have reduced general fund monies, but wouldn’t have affected the school funding formula, and money wouldn’t “follow” the student from public to private schools, so on a per-pupil basis, anyone taking advantage of this would actually be increasing the per-student school funding in that district.

The other argument is that the public schools will suffer when the “better” students leave to go to private school. This claim is absurd on the face of it. If the better students are leaving, it’s because their parents think they can do better in a private school and are willing to pay for the privilege. Those parents are surely under no obligation to subject their children to an inferior education in addition to paying for it while they wait for their local school board to figure out what to do. The only way this claim makes any sense at all is if the mere existence of private schools poses a threat to public education.

This latter argument, by the way, was what swayed a majority of the local Jewish Community Relations Council not to support 1221, even though it would have made a substantial difference to many families struggling to pay day school tuition. Because apparently education is a Jewish value, unless it’s Jewish education.

The other product of the Bad Idea Factory is a government-run 401(k) for everyone in the state, known as HB18-1298. The bill reprises last year’s similar effort. Every business in the state with more than a certain number of employees, who doesn’t offer a retirement plan, would be required to participate in the state’s plan, and employees would be automatically opted in to participation, with the ability to opt out. That number of employees would ratchet down, going from 100 to 5 over a period of three years.

The real effect here – perhaps even the goal – is to force out privately-run 401(k) plans. It would have the effect of concentrating investment power in the hands of the government, and eventually forcing us all into the same, government-run retirement system. And they call me ideological.

More subtly, the authors of the bill accept at least two premises that those of us pushing for reform of the state’s catastrophically underfunded public pensions have been making for years. First, the bill explains that the DC plan won’t add to the state’s liabilities. Second, by making the plan opt-out rather than opt-in, they admit that default choices are sticky, that people tend to stick with them even if the effort required to switch is low. Which is why they want PERA to continue to default to the DB plan.

Third, and most critically, they admit that a DC plan can help people save for retirement in a constructive way that helps ensure security. And it raises the question – if a DC plan isn’t good enough for teachers and state employees, why is it good enough for the rest of us?

Most factories, if they continued to turn out products like these at such a rate, would go bankrupt and close up shop. The Democrats and the Left went intellectually bankrupt at least a decade ago, but unfortunately, don’t show any signs of going out of business.

Republic vs. Democracy

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on March 28th, 2018

Say, “our democracy,” and it shall follow as the night the day that a libertarian will pedantically correct you, “We’re a republic, not a democracy.” This is usually said hearkening back to the Founders, and of course it’s technically correct. We are, or at least were designed to be, a representative republic and not a direct Athenian democracy.

I can state with some confidence that the number of people it’s persuaded is in the low single-digits. Neither those being corrected nor those listening in are likely to second-guess their opinions on whatever subject is at hand, and there’s a good reason for that: our elections are democratic, we frequently have ballot measures that are decided by majority democratic vote, and people use the word “democracy” in common parlance all the time without thinking, “What Would Pericles Do?”

Most of the time, it’s both annoying and irrelevant.

A recent Washington Post oped decried the practice of “gunsplaining,” or pointing out that gun control activists often don’t know very much about the items they’re trying to regulate or ban. The author argued that the sole purpose of correcting factual mistakes is to bully gun-control advocates into silence. In my experience, bringing up the fact that there’s no such thing as a “full semi-automatic mode,” or noting with some derision that a Congressman, who’s actually empowered to make laws on this subject, describes a non-existent, “shoulder thing that goes up,” serves a different purpose.

Most of the gun-control activists and legislators in this country are on the left, which has spent the last century or so quietly and not-so-quietly shifting control over our lives to a bureaucracy of experts. We are expected not merely to defer but to actually give thanks for this growing rule-by-enlightened-bureaucrat. But when the subject turns to firearms, these very same people turn ignorance into a virtue. “Gunsplaining”, in its best form, is used to make sure that we’re all talking about the same thing, as with any technical subject, and to make sure that people who want to impose new laws or regulations don’t make them overly-broad. It’s not contemptuous; it pays the other party the respect of assuming that they’re acting in good faith.

To shout, “We’re a Republic, not a democracy!” in the middle of a gun control discussion doesn’t do any of that, because it’s not really relevant to the subject at hand.

There are plenty of cases where it does matter. If the discussion is about eliminating the Electoral College in favor of a mythical National Popular Vote, or Colorado’s recent Amendment 71, changin

g the way that Constitutional amendments are adopted, govsplaining is entirely appropriate. Like gunsplaining, it assumes that the other side is discussing the issue in good faith, may simply not recognize the difference between the two or the difference it makes, and tries to reach some understanding of terms that matter. Govsplaining should be confined to those instances, but usually isn’t.

Contrary to popular opinion, this confusion is not a recent development, nor does it represent a catastrophic failure of our educational system, although there are plenty of those. Allow a lengthy quotation from Gordon S. Wood’s Empire of Liberty towards the end (pp. 717-18), where he’s discussing the changes between 1789 and 1815 in our early Republic:

If indeed the Americans had become one homogeneous people and the people as a single estate were all there was, then many Americans now became much more willing than they had been in 1789 to label their government a “democracy.” At the time of the Revolution, “democracy” had been a pejorative term that conservative leveled at those who wanted to give too much power to the people; indeed Federalists identified democracy with mobocracy, or as Gouverneur Morris said, “no government at all…”

But increasingly in the years following the Revolution the Republicans and other popular groups, especially in the North, began turning the once derogatory terms “democracy” and “democrat” into emblems of pride. Even in the early 1790s some contended that “the words Republican and Democratic are synonymous” and claimed that anyone who “is not a Democrat is an aristocrat or a monocrat.” …soon many of the Northern Republicans began labeling their party the Democratic-Republican party. Early in the first decade of the nineteenth century even neutral observers were casually referring to the Republicans as the “Dems” or the “Democrats.”

With these Democrats regarding themselves as the nation, it was not long before people began to challenge the traditional culture’s aversion to the term “democracy.” “The government adopted here is a DEMOCRACY,” boasted the populist Baptist Elias Smith (pictured) in 1809. “It is well for us to understand this word, so much ridiculed by the international enemies of our beloved country. The word DEMOCRACY is formed of two Greek words, one signifies the people, and the other the government which is in the people…. My Friends, let us never be ashamed of DEMOCRACY!”

We all know the difference between a representative republic and a direct democracy. The Americans of 1790-1810 knew it, too. I suspect when pressed, most Americans even now understand the difference. It’s important not to let corruption of the language degrade our understanding of institutions, and eventually our institutions themselves. But it’s most important when it’ll do some actual good.

SB200 Passes the Senate With No Democrat Votes

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on March 27th, 2018

SB200, the PERA reform bill, has passed the State Senate on a party-line 19-16 vote, with Sen. Cheri Jahn (U) joining the majority Republicans in support.

SB200, the PERA reform bill, has passed the State Senate on a party-line 19-16 vote, with Sen. Cheri Jahn (U) joining the majority Republicans in support.

It faces a tougher road in House, where the Democrats have a 10-seat majority, pending a Republican successor to evicted Rep. Steve Lebsock (D-R) in House District 34. But the bill has Democratic support, even among leadership. Majority Leader K.C. Becker (D) is one of the sponsors, and she’s been working with Sen. Jack Tate (R) since the beginning to get something written that can both pass and do more than just tweak things until the next crisis.

With a minority in the Senate, and the Republicans solidly behind the bill as amended, it was easy for Democrats to vote to oppose. They took no risk in doing so. What they could do was propose amendments that laid down markers for what the unions party expects to see changed coming out of the House and headed into a presumed conference committee. I covered those in a previous post, but they amount to:

- Reducing the employee contribution increase

- Increasing the employer contribution

- Not increasing the retirement age

- Not expanding access to the Defined Contribution plan

- Increasing the COLA cap

- Eliminating the new oversight committee

Now is where the Senate Republicans and House Democrats who have been leading the effort will really be tested. The needle to thread is much narrower, with Republicans more likely to vote against a substantially weakened bill, but Democrats potentially demanding more change to vote for it.

The Senate Democrats, in particular Sen. Rachel Zenzinger, complained that they were willing to compromise but that the Republicans had rejected such efforts. In fact, the final bill represented serious compromise from the Republican desiderata going in.

Will Becker and her co-sponsor Rep. Dan Pabon (D) be able to corral enough House Democrats to avoid poison-pill amendments, and have Sens. Tate and Priola been clear and convincing about just what those red lines are? Should a weakened bill make it out of conference, will enough Senate Republicans vote against it to offset any pickup in Senate Democrats. Recall that in the Senate Finance Committee, Sen. Jahn actually voted to support two amendments by Sen. Lois Court (D-Not Math) that ended up being proposed again on the floor.

We’re far from done. Let’s just hope they’re not still marking up amendments the first week in May.

Sen. Dan Kagan Emerges as Defender of PERA

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA on March 26th, 2018

In Friday’s debate on SB200, the PERA reform bill, Sen. Daniel Kagan (D-Cherry Hills) emerged as the floor leader of those fighting to defend the current system. Neither his positions nor his prominence on this issue should entirely be a surprise to observers.

Kagan’s district isn’t particularly left-wing: it’s got a 32000 – 27000 Democrat-to-Republican registration advantage, but also has 35,000 Unaffiliated voters. Kagan won his race against Republican Nancy Doty 53% – 47% in 2016, running slightly behind Hillary Clinton, who got 56% of the three-way vote among herself, Donald Trump, and Libertarian Gary Johnson. Located in suburban Denver, it’s a battleground district, but because of its loction also has a lot of PERA members and retirees.

Kagan reliably votes the Democratic line and has since his time in State House of Representatives, but has a way of conducting himself with civility and generally respects even hostile witnesses who come before his committees. The plummy British accent born of a well-to-do aristocratic upbringing probably doesn’t hurt as a public face, either.

On Friday, Kagan proposed three separate amendments, all of which could well have been written by the unions. The first would have restored an increase in the employer contribution, a 1.5% increase as compared with the 2.0% increase that was amended out in the Finance Committee. He used the traditional phrases about “shared sacrifice,” but also noted that the SAED enacted in 2006 was supposed to come from money from foregone raises, claiming that the nominal current 20.15% overstates the actual employer contribution.

This is an argument rejected by both the governor’s office and even PERA itself, whose former executive director, the late Greg Smith, testified before committee that it was his impression that school boards around the state were eating the SAED themselves rather than taking it out of teacher pay.

Next, he moved an amendment to raise the COLA cap from 1.25% to 1.75%, although he didn’t speak to that amendment.

Finally, he proposed L-013, comprehensively different plan altogether. These sorts of amendments are called “strike-through” amendments because they strike-through the whole of the bill, seeking to replace it with something else. In this case, the “something else” would restore the employer contribution to 1.5%, lowered the increase in the employee contribution to 1.5%, capped the COLA at 1.75%, increased the Highest Average Salary calculation from 3 years to 5 years (as opposed to the 7 in the bill), rescinded the increase in the retirement age, kept the calculation on net pay rather than gross pay, and prevented the expansion of the DC plan availability to all employees.

He defended this proposal by arguing that the plan’s actuaries confirmed that, according to their assumptions, it would put PERA on a path to 100% funding in 30 years. He claimed that PERA was not in “crisis” as in 2010, but did lack “resiliency,” especially since the adoption of more “conservative” assumptions. The language here is important. The term that the PERA Board would use for its November 2016 revisions in the expected rate of return and mortality tables is “realistic,” but this is incorrect – they are more conservative, and still far too optimistic. It is those assumptions that the actuaries are operating under.

He also derided the expanded DC plan availability as a “poisoned chalice,” that most PERA members rejected in favor of the shared responsibility and pooled resources of a DB plan that would always be there for people. I think it should be obvious to all but the most blind observer that the experience of the last 20 years shows that, absent continual adjustments, benefit cuts, and increased taxpayer contributions, the DB plan will not “always be there.”

Debate on this amendment – backed by the unions – will continue Monday morning when the Senate reconvenes.