Archive for category History

Mixed Feelings About UN Holocaust Remembrance Day

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Israel, Jewish on January 27th, 2013

Today is the UN’s annual Holocaust Remembrance Day. It’s commemorated on January 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army, and is generally pointed to, even by UN critics, as one of the few things that the UN gets right. For its admirers, the day pretty much absolves the UN of all sins.

I confess to having mixed emotions about it.

First, there’s the tendency towards universality that pervades everything Jewish-related that the UN does. The Holocaust has a specific, unique meaning to Jews that it doesn’t have to anyone else. This is a result of the special place that Jews held in Nazi ideology, and therefore the uniquely catastrophic results that the Holocaust had on the Jewish population and civilization of Europe. This point has been made before, but the need to draw universal lessons from a uniquely Jewish experience has the effect of lessening, rather than deepening, the lessons that we actually draw from it. It’s much easier, much more banal, to oppose “hate” in the abstract, than it is to look at the much more concrete way that a specific person or people is seen.

That universality has been the Trojan Horse by which, ironically, anti-Semitism has been given a new lease on life, when the Holocaust was supposed to have rendered it inert for all time. As British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has repeatedly pointed out, anti-Semitism is a virus, that mutates into whatever form the current zeitgeist finds most acceptable. Currently, racism is the one thing that can’t be tolerated. Therefore, it is convenient to condemn Israel – and Jews – for supposed racism vis-a-vis the Palestinians. Rebutting those charges is well beyond the scope of this blog post, and well-nigh impossible in the eyes of those who make them in the first place. But the charge of racism, accompanied by the de rigeur comparisons of 2013 Israelis to 1943 Germans, is what has allowed anti-Semitism to regain respectability within the Left. It will provide the cover for the very same diplomats shedding crocodile tears over the dead Jews of 70 years ago to condemn the living Jews of today for resisting a repeat of history.

In fact, there already is a Holocaust Remembrance Day in Israel, Yom HaShoah, and it celebrates life, vitality, resistance, and renewal, rather than the passive liberation and victim-status that the world prefers for its Jews. Two days were considered – first the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, 14 Nissan. That was rejected because of its proximity to Passover. Instead, Yom HaShoah is commemorated a week before Yom HaAtzmaut, Israeli Independence Day. Either one of those would be just fine for a UN Holocaust Remembrance Day, but either would make more difficult the UN’s current mission of demonizing and dispossessing the Jews of their national homeland.

If a Day of Liberation of the Camps were strictly necessary, perhaps the anniversary of the liberation of one of the camps by Eisenhower, who actually commissioned films to be made in order to perpetuate the awful memory of what happened. Instead, we get the liberation of Auschwitz, the Symbol of Symbols of the Holocaust, but one which was also liberated by the Red Army, which turned out to be in many ways, not much better than the Wehrmacht, and was servant to an ideology in every way the equal of Hitler’s.

Perhaps more ironically, there is a way to redeem this date specifically with respect to Jews. In 1945, as in 2013, it falls on Parshat Beshallach, the week where Jews read of the crossing of the Red Sea and the destruction of Pharaoh’s armies. Carrying the story a little further, we also read of the Amalekites attacking the Jews in their new sanctuary, with the intent of annihilating them, and the Jews’ success in fighting them off.

Don’t count on too many people pointing out those parallels.

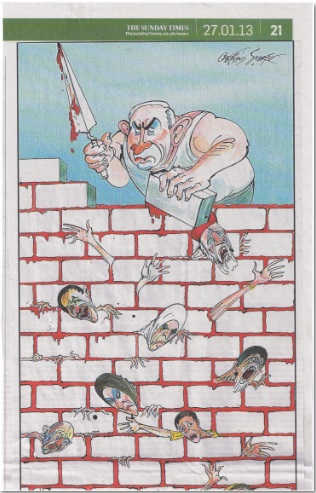

UPDATE: As if to make the point, here’s a front-page cartoon from this morning’s Sunday Times of London:

Dems Try to Tar Republicans With…Slavery?!?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, History, National Politics, PPC on January 17th, 2013

Gawker seems to think it has a scoop of some kind, trumpeting the fact that the Republicans are meeting in the Burwell Room of the Kingsmill Resort (named for a formed slave plantation) to discuss – ta da! – minority outreach. The irony, the sheer hypocrisy of such a thing is apparently too much for them to bear. And local DU polisci professor Seth Masket, on Twitter, is equally enthralled.

Let’s remember that the GOP is the reason that neither Burwell Plantation nor the location of the resort are slave plantations any more. Masket knows this, but still thinks that somehow the GOP is tarred by association with slavery.

Of course, the Democrats have been holding retreats there for years (1998, 2007, 2008, 2009 – where President Obama spoke), and President Obama did his 2nd debate prep there this past year, without anyone commenting on the location. There’s a good reason for that – it doesn’t matter. Many fine resorts in the south are located on former plantations; it’s a good use for the land. That it was a plantation 150 years ago should be cause for celebration.

If anyone has reason to be embarrassed about holding meetings there, it’s the party of slavery and secession, not the GOP.

Mitt Romney as Adlai Stevenson

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, History, National Politics, PPC on December 24th, 2012

These comments by Mitt Romney’s son Tagg have gotten a lot of attention in the last couple of days:

In an interview with the Boston Globe examining what went wrong with the Romney campaign, his eldest son Tagg explains that his father had been a reluctant candidate from the start.

After failing to win the 2008 Republican nomination, Romney told his family he would not run again and had to be persuaded to enter the 2012 White House race by his wife Ann and son Tagg.

“He wanted to be president less than anyone I’ve met in my life. He had no desire… to run,” Tagg Romney said. “If he could have found someone else to take his place… he would have been ecstatic to step aside.”

By coincidence, I happened to be reading Joseph Epstein’s profile of Adlai Stevenson in his new book, Essays in Biography. To the extent that these revelations can be taken at face value, the resemblance to Stevenson’s approach to power is remarkable.

Let’s start by acknowledging some differences between Stevenson and Romney. While both were bright, Romney is probably more intellectual than Stevenson was (Stevenson played the part of the intellectual better, but the only book on his nightstand when he died was the social register), and Stevenson was probably a better governor. He could have had the 2nd term in Illinois if he had wanted it instead of the presidential nomination, whereas it’s not clear at all that Romney would have had a 2nd term if he had run, rather than prepare for his 2008 run.

But both Romney and Stevenson appear to have had a healthy, philosopher-king style distrust of power, enough that it evidently made them each uneasy about having it themselves. That’s not necessarily the reason they lost, but in Stevenson’s case, his public prevarications seem to have projected enough weakness that the public went the other way. At least Romney had the sense to keep any doubts private. And while he made the strategic error of not answering the personal attacks sooner, nobody really thinks that’s because he was trying to take a dive.

Stevenson, like Romney, also seems to have lacked a coherent governing philosophy. In Epstein’s telling:

The style, it is said, is the message. But in the case of Adlai Stevenson, the style seemed sometimes to persist in the absence of any clear message whatsoever. He preached sanity; he preached reason; his very person seemed to exert a pull toward decency in public affairs. Yet there is little evidence in any of his speeches or writing that he had a very precise idea of how American society was, or ought to be, organized. His understanding of the American political process was less than perfect, as can be seen from his predilection for the bipartisan approach to so many of the issues of his time. One might almost say that Stevenson tried to set up shop as a modern, disinterested Pericles, but that he failed to realize that the America of the 1950s was a long way from the Golden Age of Athens.

Ultimately, Stevenson was better at not saying much; his rhetoric influenced both Kennedy’s New Frontier and Johnson’s sale of the Great Society; whomever the Republicans nominate in 2016 will likely owe little to Romney’s campaign talks.

I don’t want to overdraw the comparison. Romney only ran in one general election; in some ways, his 2012 race contains elements both of Stevenson’s initial 1952 run and his rematch with Eisenhower in 1956, but in other ways, was completely different. Having never been the party’s nominee in 2008, Romney couldn’t lead the party in-between elections. The Republicans as a whole are coming to understand what Stevenson learned in 1952 – that a Presidential campaign is a terrible place to define issues and educate the public; individual personalities simply play too large a part in any single-office election.

But the biggest difference is how Romney will react after his loss, compared to how Stevenson reacted after his. Stevenson desperately wanted the nomination in 1960, only couldn’t bring himself to say so until it was too late. He wanted it, but he wanted to be asked, rather than having to ask. Romney really does seem done with politics, except for the inevitable post mortems.

Thanksgiving 2012

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, PPC on November 22nd, 2012

Susie and I went to New England for a couple of weeks this summer. It’s a part of the country I had never really been to before, which meant that I probably tried to cram too much into the two weeks. Hey, you never know when you’re going to be back – maybe never. So what’s the point of driving from Cape Cod to Bah Hahbah, and not making a brief pit stop at Plymouth?

I grew up in Virginia, the son and grandson of Tidewaterites, so I got to see the Virginia pole of the colonial experience pretty extensively. Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown are all within a quick drive of each other, and we took advantage. But I had never been to the Massachusetts pole of the Axis of Colonial America, Plymouth. (Boston is sui generis, and could be the subject of a whole trip all by itself.)

You know the story. The Pilgrims land here in 1620…

…things don’t go so well for them, so the Indians step in, help out with food and local know-how, and everyone celebrates together.

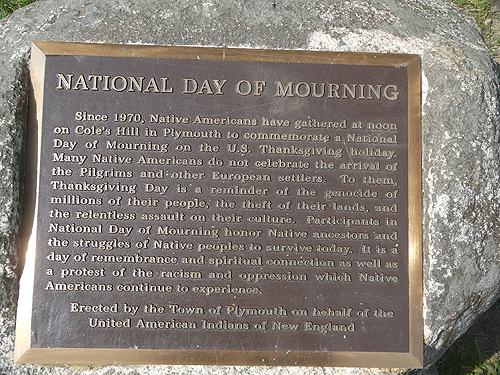

A few yards from Massasoit is this rather sour marker:

Hey, it’s a free country. This group of Indians want to come to Plymouth and mourn the fact that they ended up dealing with the English rather than the Spanish, I guess that’s their right, but it’s shame that the 1998 settlement had the city of Plymouth put up a plaque celebrating that.

This is where it started, the northern part at least, and it’s wrong that the city where it all started is coerced into turning the holiday into another excuse for an apology for success and constitutional government.

Even then, it’s only half the story. It turns out that while the Indians did make the difference that first couple of years, the colony was really failing because it was a socialist experiment. Once the colonists figured out that people work harder when they work for themselves, things really took off:

It’s wrong to say that America was founded by capitalists. In fact, America was founded by socialists who had the humility to learn from their initial mistakes and embrace freedom. One of the earliest and arguably most historically significant North American colonies was Plymouth Colony, founded in 1620 in what is now known as Plymouth, Massachusetts. As I’ve outlined in greater detail here before (Lessons From a Capitalist Thanksgiving), the original colony had written into its charter a system of communal property and labor. As William Bradford recorded in his Of Plymouth Plantation, a people who had formerly been known for their virtue and hard work became lazy and unproductive. Resources were squandered, vegetables were allowed to rot on the ground and mass starvation was the result. And where there is starvation, there is plague. After 2 1/2 years, the leaders of the colony decided to abandon their socialist mandate and create a system which honored private property. The colony survived and thrived and the abundance which resulted was what was celebrated at that iconic Thanksgiving feast.

Perhaps not surprisingly, I really had no idea about this part of the story until I read about it in the Wall Street Journal about 10-15 years ago. The story I heard was the one that essentially leads to the conclusions at top: the Indians saved the day, and other than the nice meal, have been regretting it ever since. The whole part about the communitarian experiment gone wrong – is there any kind that goes right? – somehow slipped everyone’s mind. It’s right there in Bradford’s journals, as Bowyer point out. Instead, we spent a couple of months rehearsing the class play, an adaptation of Witch of Blackbird Pond.

This is a shame not just because it passes up a chance to teach an obvious lesson about economics and human nature. It also misses a chance to point out the roots of our Constitution. (Honestly, everything before 1787 should be taught as a lead-up to the Constitution. There’s a reason they wrote what they did; it didn’t just come out of nowhere.) The colonies really were different in outlook. New York was founded as a commercial colony. Massachusetts wasn’t and the Puritan ethic echoes still. Federalism wasn’t just a matter of keeping the federal government in check, it was also a way of respecting different outlooks on life.

I’m not such a big fan of politicizing our national holidays. The point of them is that their national, not partisan or political. They’re supposed to be things that we all celebrate or commemorate together. (We’ll talk about Christmas some other time.)

So let’s remember and be thankful that, for the fact that, even with all the unfortunate changes over the last few years, we’re still living in the only country founded on an idea, and hope that over time, we can find our way back to it.

Jacques Barzun, RIP

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 25th, 2012

You would think that a death so long anticipated wouldn’t have much effect, but it doesn’t work that way. Jacques Barzun, cultural historian, iacademic, intellectual, and evangelist for Western culture, died today just a month short of his 105th birthday, and it still seems a shame. He was part of that glorious mid-Century intellectual atmosphere that not only sought to think, but to think publicly and to make its thinking accessible to the public at large.

Many of Barzun’s books are scattered about the house, in various parts of the library. I’ve read some, and will read the rest. I worked my way through his magisterial From Dawn to Decadence when it came out, when he was a mere 93. I nibbled at The Culture We Deserve. I’ve read most of his essays in A Reader’s Companion, (brilliantly reviewed by Joseph Epstein).

I have a first edition of his 1959 critique of the suicide of American intellectuals, The House of Intellect, along with two reviews of it, one by Harold Rosenberg and the other by Daniel Boorstin, future Librarian of Congress, no pikers they. When you merit having your books reviewed by them, you know you’ve arrived.

I have an unerring appreciation for books despised by their prolific authors. From what I can tell, Peter Robinson would just as soon forget Postcards from Hell, about his time at Stanford Business School, and Richard Miniter has never responded to my compliments for The Myth of Market Share. For some reason, I always figured that Barzun felt the same way about God’s Country and Mine, an appreciation of the culture of mid-Century America as only an immigrant can appreciate it. (Clifton Fadiman liked it, which may by itself be enough to spark a re-appraisal on my part.) Latino immigration may have changed this, but for about a century, more of us were descended from Germans that from any other European race, a fact not lost on Barzun, the French American-by-choice:

Our popular culture Germanic? Yes. It is not merely that at Christmas time we all eat Pfeffernusse and sing “Heilige Nacht,” nor that our GIs in the last war found ever country queer except Germany….

One could go on forever; our appalling academic jargon bears a deep and dangerous likeness to its German counterpart; our sentimentality about children and weddings and Christmas trees; our taste in and for music; our love of taking hikes in groupsm singing as we go; our passion for dumplings and starchy messes generally, coupled with our instinct for putting sweet things alongside badly cooked meats and ill-treated vegetables – all that and our chosen forms of cleanliness (every people is clean in different ways about different things) show how far a characteristic culture has spread from the three or four centers where Germans first settled.

Barzun first came to my attention in high school, not for his academic work but for his Modern Researcher, which he continued to update for decades. He kept it updated for decades, but the brilliance of the book isn’t in the technologies it describes, but in the basic fundamentals of the detective work, and how to keep your notes and mind orderly enough to make sense out of what it is you’re finding. When you’re done researching, keep Simple and Direct on your desk, open, next to Strunk and White. There’s a video of him discussing writing a couple of years ago with a small group in San Antonio, where he lived. Folks, this is a video of a 102-year-old man, and there are days when I don’t feel as lucid as he is in this video.

One of the gifts that Barzun’s long life bestowed on us was an embarrassment of mature work. Consider that when he wrote God’s Country and Mine, he was 47, one year older than I am now. This is the book of a mature man, and almost all the work I have from him is later than that. A huge percentage of what he wrote came with a lifetime or more of experience and seasoning. When he defended the value of the Western intellectual tradition and culture against the barbarians, he knew what we were in danger of losing. This wasn’t a political defense; it was born of an understanding that the West said things that had never been said before or since, and to abandon that tradition was in a very real sense criminal neglect of some of mankind’s greatest, most liberating ideas.

He could stand neither Marxism nor the self-loathing of American that it brought to academia. It’s only justice that as long as the execrable Eric Hobsbawn lived, Barzun, 10 years his senior, outlived him. Bully.

As I’m writing this, obits are being prepared all over academia, and Arts and Letters Daily will hopefully have a round-up of them tomorrow. I’ll pick out the best and link to them here.

Forward! To The 1870s!

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, History, National Politics on September 23rd, 2012

A lot’s been made in the last few days about the new Obama campaign “flag,” which replaces the 50 stars with the Obama campaign symbol. (After all, who need 50 stars when you can get by with The One?) As a counterpoint, some on the left have taken to posting Lincoln campaign flags, and a few of my friends on the left haven’t been above calling conservatives names over their outrage. It turns out it wasn’t just Lincoln who did this – it was a fairly common, almost standard campaign motif from about 1840 to William McKinley. I’ve collected a slideshow (although those of you reading this in email will need to go to the site to see it):

Then, starting in the very late 1800s, around about the same time that we started to take our place on the world stage, our attitude about the flag started to change as well. In 1898, the poem, “Hats Off!” was published. It was still current as late as the 1960s, when it was being republished in a book I read as a kid. The Pledge of Allegiance was published in 1892, as well. (Ironically, Francis Bellamy was a Christian socialist, but nowadays it’s the “right-wingers” who open meetings with it. It was written in the days when American socialism was more nationalist, and less Internationale, I suppose. Good thing they dropped the salute, though.) And in 1924, the Code of Conduct for the Flag was finally enacted, about a generation after the flag’s started to become a more venerated symbol. By that time, of course, putting your picture on the flag had long gone out of fashion.

Does this mean that the Obama campaign flag is much ado about nothing? I don’t think so. I was never outraged by the appropriation of the flag, but I did consider it to be just another example of the creepy cult of personality that Obama seems way too comfortable with, and which is completely inappropriate for a sitting president of a democratic republic. Harsanyi missed this year’s DNC logo, a stylized Obama campaign “O.” I looked back at convention logos of both parties from 1980 onward, and didn’t see anything remotely like that for either party. He also didn’t mention the other weird stuff, like making an “O” with your hands in 2008, and the Obama Campaign Wedding Registry.

We’ve lionized presidents before, but usually after they’ve left office. Lincoln, FDR, Kennedy, and Reagan come to mind. Three of them died in office, three led us through decisive moments in major struggles. (JFK’s persists to this day. I was looking at a poster of presidential portraits in DAT this morning, and while almost all were the official presidential portrait, Kennedy’s was of his standing with his hand on his desk, head bowed, in a golden haze, which struck me as a little over-the-top. Fifty years on, that sort of thing isn’t doing anything to encourage serious appraisals of his time in office, is it?) But I can’t remember anything like this for a living President, and Obama’s the eighth one I’ve been conscious of.

Certainly the way that Obama did this is different from what came before. In some ways, the redesign does more violence to the flag than the portraits did. The Obama “O” is a paler shade of blue, cyan really. And the previous presidents and campaigns at least kept the stars there, rather than replacing them entirely. But I’m sure that if he had put his portrait, or a stylized, dark blue monochrome of the Sheperd Fairey poster there, and kept the stars, it would still have been weird. It’s not just about the design elements.

My friend State Senator Shawn Mitchell put his finger on it when he said that campaign symbols, indeed any political symbols, are created in a particular time and a particular environment. In the 1870s, people were used to seeing this sort of thing. Now they’re not.

The claim that this is just reviving an old tradition of flag redesign doesn’t ring true, not in today’s context. A lot’s changed since the late 19th Century, and how we think about the flag is only part of it. Maybe it was more acceptable when the Republic was younger. Maybe there was a recognition that the presidency was itself, in some way, a national symbol, and that in the days before the federal government has usurped so much of the states’ powers, there was less danger in any one individual who occupied the office.

So how about a deal. We’ll stop complaining about Obama “desecrating” the flag, if they’ll pare back the Federal Government to the scope it had in 1876.

Grey Eminence

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Defense, History on July 8th, 2012

by Aldous Huxley

by Aldous Huxley

Most people know Cardinal Richelieu as the architect of France’s foreign policy during the reign of Louis XIII and the Thirty Years’ War. Less well-known is his right-hand man, Father Joseph du Tremblay, the subject of Aldous Huxley’s biography Grey Eminence, which has been called the “best book on the intelligence operations of the French state” of that period.

Father Joseph was a Capuchin monk, and even before entering politics, a serious mystic, whose successful evangelism seemed merely to take time from his efforts to achieve union with the Godhead. His piety was not a pose; he would continue to honor his vow of poverty to the point of rigorous self-denial, right to the end of his life. In their personal lives, Richelieu lived in luxury, while Joseph lived the Church teachings.

The question that fascinates Huxley is how a fellow mystic, so loyal to the Church and its divine mission, could devote his public life to the perpetuation of what amounted to a war of extermination in Germany. It was a question that Fr. Joseph’s contemporaries asked, and one that marred his reputation almost from the time he took office. It would follow him even to his funeral.

To fully understand what’s at stake, one needs to understand the position that the Thirty Years’ War holds in German history. The war’s destructiveness was unmatched for its time, killing about half the German population, reducing the rest to utter poverty and starvation. Armies, foreign and domestic, pillaged what food their was, and destroyed urban production.

It was the conscious policy of France – both Richelieu and Joseph – to extend it as long as possible, precisely to inflict this damage on France’s most dangerous continental rival.

For Richelieu, the motivation is easy to see. But when Father Joseph took a position as Richelieu’s right-hand diplomat, the motivations were a little more subtle. Joseph identified France’s interests with God’s. He seems to have truly believed that a strong France would advance the Church’s interests in the world. More than anything, he wanted another Crusade against the Turks, to recover Constantinople and the Holy Land. (Constantinople had only been Ottoman for about 150 years; Christian rule there wasn’t a living memory, but it also wasn’t terribly distant, and much if not most of the city’s population remained Orthodox.)

Spain had actually expressed interest in the enterprise, but wanted overall leadership. To Joseph, anything other than French leadership was unimaginable. In order to accomplish a French-led Crusade, France would not only have to turn Germany into a highway for Catholic troops, it would also have to break the power of the encircling Hapsburgs, who sat on the thrones of both Spain and Austria. Thus France’s support for the Dutch resistance to Spanish rule, and the strategic support of the Lutheran Swedes against the Austrians, using Germany as their battlefield. Catholic France’s support for Protestant armies against other Catholic powers only fed the cynicism about its motives.

That such cynicism existed at all was a result of the mixture of religious and political roles, and of religious and nationalistic motives. The Peace of Westphalia has been seen as establishing a secular international order. But such an order was only possible because governments – even diplomats who had Church titles – had been pursuing a nationalistic foreign policy for decades beforehand. Only such a worldview can explain France’s actively promoting German bloodshed almost as an end unto itself, and delaying a crusade until France could lead it.

David Goldman, a.k.a. Spengler, flatly states that our position with respect to the Muslim world is roughly that of France of the early 1600s to the rest of Europe. Still the main power to be reckoned with, we should pattern our Middle East policy on France’s: divide and weaken, intervening only directly when absolutely necessary. And just as France became the dominant European land power for over 200 years after the War, so we can manipulate the Sunni-Shia divide to our advantage.

And yet, Huxley, in a somewhat mystical moment, notes simply that violent actions rarely if ever have salutary results. Germany remembered. Germany rose to challenge France, and Germany never really forgot the horrors that French diplomacy had visited upon it. It was a vengeance that was fueled by a moral indignation, as well, that France had posed as a religiously-motivated power, even as it reduced Germany to cannibalism.

Huxley answers his central question by concluding that Father Joseph simply bargained away, piece by piece, the practical tenets of his mystical faith in pursuit of his more concrete policy goals. At a personal level, his extreme piety convinced him that God would forgive whatever compromises he had to make to ensure France’s success.

We too have our ideals, that such a purely realpolitik foreign policy would betray. And years down the line, some future Huxley might also find that, in pursuit of national interests, we had, little by little, allowed ourselves to completely bargain them away.

Thucydides The Revisionist

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Iran, War on Islamism on November 21st, 2011

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History

Prof. Donald Kagan

Since it was written, the prism through which we study the Peloponnesian War has been Thucydides’s History. Virtually everything we know about the war, we know through his writing. It was Thucydides who established the first recognizable historical standards, eschewing myth and legend in a way that even Herodotus did not.

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History is Donald Kagan’s attempt to apply – finally – the same critical approach to the History as we do to virtually every other historical record. What makes it special is that it’s not merely Kagan’s attempt, it’s pretty much the only recent attempt to do so.

There must have been different opinions. A war as long-lasting, as all-consuming, as destructive as the Peloponnesian War, must have produced different contemporaneous interpretations. And yet, as Kagan points out, so effectively has Thucydides established his point of view as authoritative, that people aren’t even aware that there were other points of view. In fact, even the facts that Kagan uses to challenge Thucydides’s conclusions come from the History itself.

Kagan would know. He’s been a serious historian of the ancient Greeks at Yale for decades now. (Yale just made his course lectures available in both video and audio online for the first time. His discussion of Greek hoplite warfare alone is worth the price of admission.) His one-volume study of the Peloponnesian War was even a popular hit. “The damn thing sold 10,000 copies,” he says, in evident amazement.

So when Kagan decides that we must treat the History not as a dispassionate academic work, but an apologia pro vita sur, we should take him seriously.

This conclusion leads Kagan to take issue with a number of Thycydides’s conclusions. Thucydides argues that the war was inevitable, the result of an insecure Sparta facing a rising and dynamic Athens, at odds with each other over the proper form of government for Greeks.

It’s true, Kagan says, that there was tension on this point. The Spartans had invited other Greeks to help them put down a Helot rebellion, and then asked the Athenians – and only the Athenians – to leave, worried about where their sympathies might really lie. Later, the Athenians do turn a captured city over to some Helots, frustrating Spartan plans to round them up and return them to servitude, and no doubt increasing their suspicion and mistrust at the same time.

And yet. It wasn’t the two principals who dragged their alliances into war, but two allies who dragged the principals along. Years earlier, with much better odds and with two armies actually facing each other in the field, Sparta had demurred. Pericles knew the Spartan king to be a personal friend and an advocate of peace between the two alliances. When the Spartans took almost a year to actually start the war, they had reduced their demands to something almost symbolic, something so minor that Pericles himself had to persuade the Athenians not to give in. Those living through those years wouldn’t have seen an inevitable conflict between superpowers, but a series of events and miscalculations leading to war.

Thucydides argues that the Sicilian disaster was the result of the unchecked passions of Athenian democracy, in the absence of Periclean wisdom to restrain it. Kagan shows instead that the general entrusted with the mission, Nicias, never really believed in it, made a series of mistakes of omission and commission, and bears primary responsibility for its failure. Thucydides, having argued elsewhere that Athens under Pericles wasn’t really a democracy, is here trying to show what happened when it became one. It’s a game partisan effort, but its central thesis is at least open to question.

Perhaps the most critical question for our times, however, has been what to make of Pericles’s war strategy, and his diplomatic strategy leading up to the war. Pre-war signals that, to Pericles, must have seemed like subtle signals to the Spartans were evidently too subtle. And his war strategy, instead of persuading the Spartans of the uselessness of fighting, merely encouraged them in thinking that they could go on fighting it out along these lines if it took all summer. Or indefinitely.

In the entanglement that would eventually lead to the war, Pericles adopted a defensive treaty with Corcyra, primarily directed against Corinth. Then, when the crunch came, he sent, from the ancient world’s largest navy, a force so small that it had to be doubled by the Athenian assembly, with instructions only to intervene if it looked as though their ally might lose. While they eventually did intervene to save Corcyra, their manner of doing so neither assuaged the Corinthians, nor earned them the loyalty of their ally.

Nor did Pericles understand the internal politics of Sparta as well as he thought. Knowing that at least one of the kings was opposed to war, he attributed to him far more political influence than he actually was able to exert in the Spartan assembly. As a result, when Corinth accused Athens of breaking the 30-Years’ Truce – in fact, Athens had stayed just within the lines – Pericles had already undercut the position of a relatively weak office.

Kagan argues that Thucydides, as a member of the Periclean political party, is seeking to recast a series of bad decisions by Pericles as part of an irresistible chain of events. Instead, his policy should be seen as one of weakness masquerading as diplomacy and moderation, combined with a deeply mistaken sense of when and where to take a stand.When Sparta did finally declare war, it eventually narrowed its demands down to a rescission of the Megaran Decree, a punitive prohibition of access to the Athenian marketplace to residents of Megara. What led Pericles to argue against a tactful withdrawal from the Megaran Decree was his belief that he had a winning strategy for the war, one that would lower its cost in terms of both lives and treasure to the point where it would be worth it to make the point, and prevent potential unrest throughout the empire. Contrary to all previous Greek strategy, Athens would barely fight. It would play rope-a-dope, letting Sparta punch itself out with destructive, but ultimately futile raids, and make it pay a price by attacking its coastal cities, as only a naval power could do. Eventually, the Spartans would decide that they couldn’t force Athens to surrender this way, and come to terms.

As we know, things didn’t quite work out that way. And yet, even as he – along with a large portion of the Athenian population – was dying from a overcrowding-enhanced plague, Pericles (reports Thucydides) said that he was happy that his strategy had ensured that no Athenians had died by force. Historians have long noted echoes of his Funeral Oration in the Gettysburg Address, but up until this point, in his handling of the crisis, Pericles reminds us more of another president.

Thucydides argues that had the Athenians but kept to Pericles’s strategy, they would have won the war. This seems to stem more from his distaste for the low political tone set by Cleon, the successful commander and politician than from the evidence. In fact, the Athenians, once they pursued an active ground war, quickly won victories and brought the Spartans to sue for peace. Merely raiding coastal cities wasn’t enough; the Spartans had to be afraid that the Athenians would pursue and offensive strategy, invade, and potentially free the helots (or at least severely disrupt the Spartan social order), to sue for peace. They had to fear being beaten, humiliated, and impoverished, not merely wasting their time.

It’s a point that those who would argue for a strategy based solely on missiles and naval power would do well to learn, and it bodes ill for a style of warfare dedicated to dismantling an opponent’s military while leaving the population at large untouched.

Likewise, societies can only absorb so many hits, even superficial ones, without reprisal, before morale begins to erode. The Germans had to re-learn this lesson in WWI, as they sought a quick victory over France, while letting the Russians advance virtually unopposed over East Prussia, ancestral home to the Junker military professionals who had concocted the war in the first place. Whether or not the troops removed from the French front to the east were dispositive is open to question; it’s certain that the second front was a distraction.

Why do we care about the Greeks? Why, even now, 2500 years later, do we still read about their wars, against each and against their neighbor, the imperial eastern superpower?

The Greeks are a lot like us, and by learning about them, we hope to learn about ourselves. Not for nothing are the twin pillars of Western civilization Jerusalem and Athens. We see in ourselves echoes of our fractious, democratic, pluralistic, pious, postmodern Greeks. If we can see what stresses a long epoch of war places on a society, we can at least avoid being surprised.

If we’ve been learning those lessons from the wrong reading of Thucydides, then we’ve quite possibly been learning the wrong lessons. If we believe that wars are inevitable, we will fail to take our decision-making seriously. If we learn that “democracy” cannot make large strategic decisions, we abandon our core value of open debate, and are likely to fail to hold our generals properly accountable.

And if we learn that we can avoid wars by looking non-threatening, and win them merely by showing that we can, we’ll lose.