Posts Tagged Election Fraud

Could Election Fraud Cost Republicans the Minnesota House?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on November 27th, 2020

It’s not the most likely scenario, but it’s certainly possible, and explaining how highlights the difficulty of detecting fraud after the fact.

For the 2020 election, the coronavirus allegedly made voting in person too dangerous to contemplate. Minnesota, like many other states, responded by trying to implement universal mail-in voting. In its case, this took the form of mailing an absentee ballot application to everyone on the voter rolls.

As John Hinderaker at Powerline documented, the process they used opened up a massive loophole:

If you receive this invitation, as I did, no identification is required to obtain an absentee ballot. You may have a Minnesota driver’s license, or maybe a Social Security number. (Who doesn’t?) But failing that, or if fraud is your object, you can check the third box. In that case, “Your identification number will be compared to the one on your absentee ballot envelope.”

“Your identification number” is not explained in the enclosed materials, but it can only refer to a bar code on the Business Reply Mail envelope that is included with each absentee ballot application. This obviously affords no ballot security. It merely will document that an application for an absentee ballot was submitted, and a ballot corresponding to that application was later cast. It provides no assurance as to who filled out that ballot.

As Hinderaker points out, this loophole is complicated by the country’s notoriously sloppy voter rolls. In many states, including Colorado, it’s very difficult to get yourself removed from the voter rolls if you move out of state, and even address updates often lag months or even years behind the move. Having walked precincts here in Denver consisting largely of apartments, I can personally attest to this.

The net result is that someone living in an apartment where multiple previous residents are still listed as voting residents could have filled out those absentee ballot applications and voted as those people. To get caught before Election Day, it would be necessary for the person in question to still be living in Minnesota, to inquire as to why they hadn’t received an application, to protest, and then to have the Secretary of State or the County Clerk investigate the possibility of upstream fraud. A Secretary of State who would promulgate such a lax process in the first place would be extremely unlikely to investigate such failures.

Given that Trump lost Minnesota by about 7 1/2 percentage points, it’s unlikely that this particular form of fraud would have been widespread enough to cost him the state. But that doesn’t mean that other races couldn’t have been affected. In this case, control of the Minnesota State House of Representatives could have been switched.

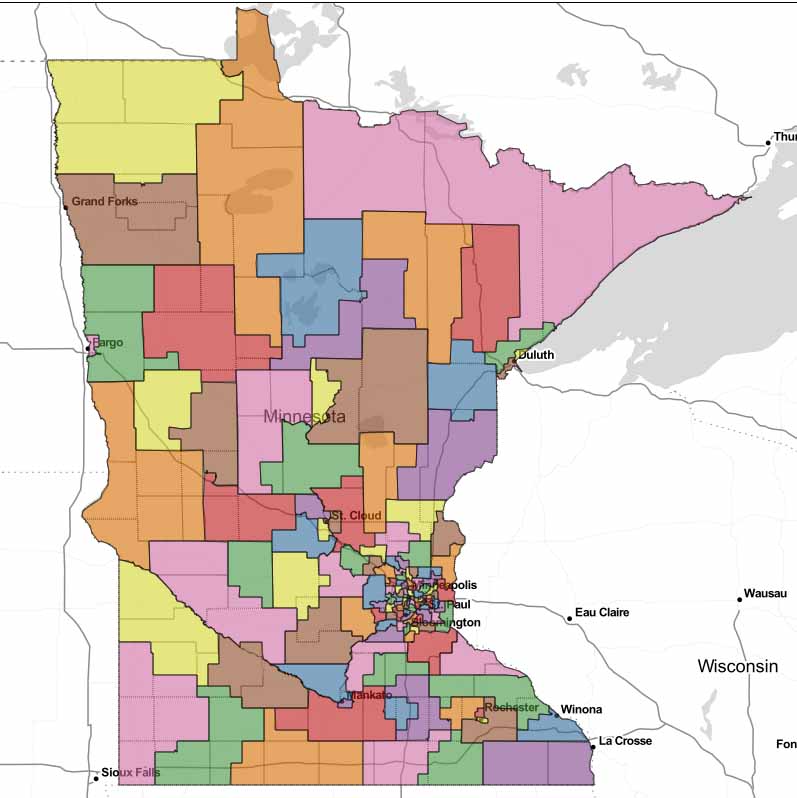

Prior to the election, the Democrats held the chamber by a 75-59 margin. As in many other states, Republicans made significant gains at the state legislative level, and on Election Night it appeared that they had narrowed the gap to 70-64. However, four state representative seats were decided by fewer than 200 votes, and those districts went 3-1 for the Democrats. Flip the three Democrat wins, and the House is split 67-67, requiring some sort of power-sharing agreement. The Minnesota State Senate is already controlled by the Republicans, so the stakes in being able to serve as a check on the state’s Democratic statewide officeholders, including the execrable Attorney General Keith Ellison, is considerable.

Each state house district consists of roughly 20,000 voters, so it would take only 1% of the ballots in any of these races to be fraudulently cast using the method described above to potentially swing the race the other way.

The problem is that such fraud would likely be incredibly expensive to detect and virtually impossible to cure. Consider the district where the Democrat won by 40 votes. If only 50 ballots had been mailed out without any ID provided or required, investigators would have to go investigate each and every of those ballots, and prove that there was something amiss. The manpower and time alone would be prohibitively expensive, and would be multiplied by at least a factor of 4 for the other three districts in question.

What’s more, once the ballot is separated from the envelope, there isn’t (or shouldn’t be) any way of reconnecting the two. If there were, it would mean that a sufficiently motivated election worker with access to the ballots and envelopes would be able to find out how any given voter had voted.

Does this mean that the Democrats necessarily retained control of the Minnesota House of Representatives fraudulently? Of course not. It does mean that it’s at least plausible, and demonstrates the extreme difficulty of dealing with fraud after-the-fact. It renders facile claims of fraud-free elections ludicrous, and it increases the chance that someone will try something like this in the future. And allowing this kind of loophole to exist is what damages the credibility of the election system, not those of us calling it out.

A Retention Vote for Morris Hoffman

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PPC on October 25th, 2012

I’ve never made any secret of the fact that I usually vote against retaining judges. It’s not out of any personal animus, of course. For citizens who are asked to keep track of so much when they vote, it’s almost impossible to learn enough law, let alone enough about every judge, to make a truly informed decision on a given judge. But we have retention votes for a reason, and it’s helpful to judges to be reminded every so often that the law belongs to the people, not to the lawyers, or even to the legislature. As long as the retention voters weren’t close, a No vote was a reasonably safe protest vote that would only tip the scales if other, well-known information about that particular judge pushed a lot of other people to vote the same way.

But times have changed, the retention votes have gotten closer, and it’s important now to reward judges who’ve actually done a good job on the bench.

So I’ll be voting to retain Morris Hoffman as a Denver judge, and I would ask all those voting in Denver to do the same.

I had the pleasure of sitting in Hoffman’s court eight years ago as he decided Common Cause v. Davidson – an attempt by Common Cause and other Democrat groups to hijack the voting rules in Colorado in order to prevent certain basic ballot security measures – and was impressed with Hoffman’s humor and ability to keep things moving without cutting people off. The opinion is readable even by laymen – not an easy thing for a judge to do when time is short and the pressure to be right is long. And the ruling itself was a model of understanding both of the role of judges and of the nature of voting.

I quoted some of the salient bits at the time, but they’re worth quoting again:

But the Court has also recognized that the right to vote, unlike some other individual rights that are exercised in essential opposition to the state, is a right that has meaning only in a highly regulated social context. A vote is not merely one individual’s casual expression of political opinion at any particular time on any particular subject. Votes count, and because they count they must be sought and given in a structured environment that allows the votes of all other proper voters to count….

Maximizing voters’ access to the process is just one part of the compelling interest the state has in regulating the architecture of elections. Preventing voters from voting more than once, preventing otherwise ineligible voters from voting, and preventing other kinds of election fraud, is part and parcel of this same compelling state interest, as the Burdick Court expressly recognized when it included the words “fair and honest” at the very beginning of its litany of state interests in structuring elections. Professor Chemerinsky had it only half right, and perhaps not even that, when, in the aftermath of the controversy of the 2000 election, he wrote “What good is the right to vote if every ballot isn’t counted?” (Erwin Chemerinsky, Fairness at the Ballot Box, 40 TRIAL—APRIL 32 (2004).) A complete description of the state’s interest in regulating elections should have included something like, “What good is the right to vote, even if every ballot is counted, if the votes of duly registered voters are diluted by the votes of people who had no right to vote?”

…

It may or may not be true, as Plaintiffs claim, that as an historical matter actual voter fraud has been rare in Colorado. But the state has a legitimate, indeed compelling, interest in doing what it can to make sure that last month’s fraudulent or no-longer-eligible registrant does not become next month’s fraudulent voter. Ms. Davidson and local election officials testified that once a fraudulent regular ballot is cast, and the voter’s identity forever divorced from the ballot, there is no way to remedy the fraud. The fraudulent vote will count. That is, election fraud must be detected before fraudulent regular ballots are cast and fraudulent provisional ballots are counted.

…

Nor do I think it likely that Plaintiffs will be able to demonstrate that the identification requirement is discriminatory or will have disparate impacts…. Plaintiffs’ suggestion that the identification requirement will “chill” people without identification may be true (though there was absolutely no credible evidence of that), but then again it may also “chill” fraudulent voters. Whether one kind of chill justifies the other is precisely the kind of public policy choice that must be made by legislators, not by judges legislating under the cover of strict scrutiny.

…

In what must surely qualify as one of the understatements of the year, even Plaintiffs’ own witness, a Denver election official, testified that allowing voters to vote in any precinct they wished “could be problematic.”

…At the moment, if I were to try to design a system that maximizes the chances that fraudulent and ineligible registrants will be able to become fraudulent voters, I’m not sure I could do a better job than what Plaintiffs are asking me to do in this case—allow voters to vote wherever they want without showing any identification.

(My own emphasis added throughout.)

For better or for worse – and probably for the much worse – courts across the country haven’t accepted these basic tenets of how a voting system ought to work, but that doesn’t make the reasoning here any less correct.

I don’t want to go overboard here. We’re talking about one decision, one data point, in a much longer judicial career. But given the stakes of the case, it’s a pretty large data point, and it’s one more than most of us will have on most of the judges. Let’s reward it.