It’s not the most likely scenario, but it’s certainly possible, and explaining how highlights the difficulty of detecting fraud after the fact.

For the 2020 election, the coronavirus allegedly made voting in person too dangerous to contemplate. Minnesota, like many other states, responded by trying to implement universal mail-in voting. In its case, this took the form of mailing an absentee ballot application to everyone on the voter rolls.

As John Hinderaker at Powerline documented, the process they used opened up a massive loophole:

If you receive this invitation, as I did, no identification is required to obtain an absentee ballot. You may have a Minnesota driver’s license, or maybe a Social Security number. (Who doesn’t?) But failing that, or if fraud is your object, you can check the third box. In that case, “Your identification number will be compared to the one on your absentee ballot envelope.”

“Your identification number” is not explained in the enclosed materials, but it can only refer to a bar code on the Business Reply Mail envelope that is included with each absentee ballot application. This obviously affords no ballot security. It merely will document that an application for an absentee ballot was submitted, and a ballot corresponding to that application was later cast. It provides no assurance as to who filled out that ballot.

As Hinderaker points out, this loophole is complicated by the country’s notoriously sloppy voter rolls. In many states, including Colorado, it’s very difficult to get yourself removed from the voter rolls if you move out of state, and even address updates often lag months or even years behind the move. Having walked precincts here in Denver consisting largely of apartments, I can personally attest to this.

The net result is that someone living in an apartment where multiple previous residents are still listed as voting residents could have filled out those absentee ballot applications and voted as those people. To get caught before Election Day, it would be necessary for the person in question to still be living in Minnesota, to inquire as to why they hadn’t received an application, to protest, and then to have the Secretary of State or the County Clerk investigate the possibility of upstream fraud. A Secretary of State who would promulgate such a lax process in the first place would be extremely unlikely to investigate such failures.

Given that Trump lost Minnesota by about 7 1/2 percentage points, it’s unlikely that this particular form of fraud would have been widespread enough to cost him the state. But that doesn’t mean that other races couldn’t have been affected. In this case, control of the Minnesota State House of Representatives could have been switched.

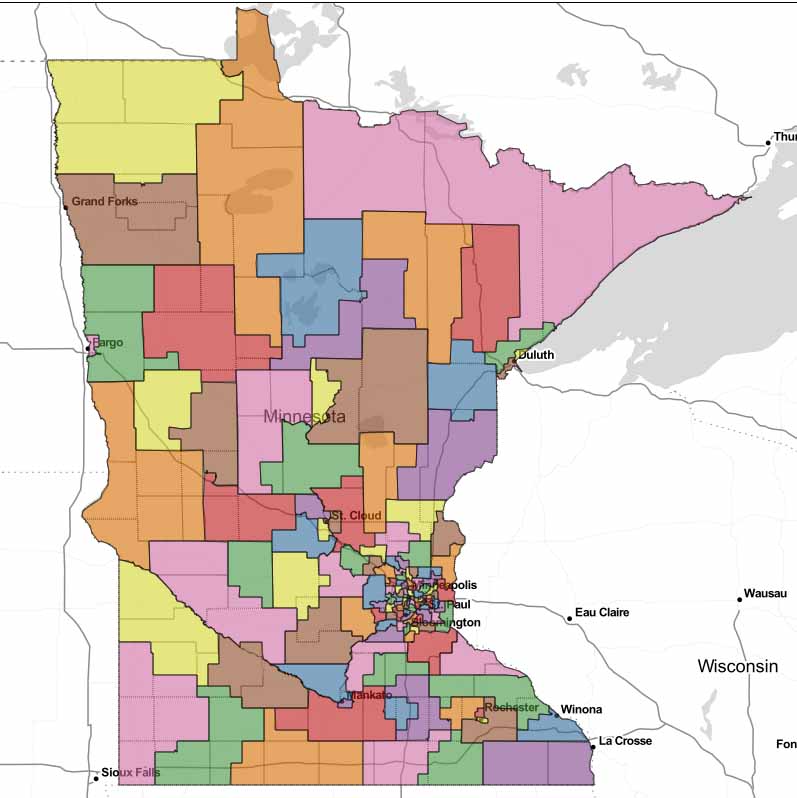

Prior to the election, the Democrats held the chamber by a 75-59 margin. As in many other states, Republicans made significant gains at the state legislative level, and on Election Night it appeared that they had narrowed the gap to 70-64. However, four state representative seats were decided by fewer than 200 votes, and those districts went 3-1 for the Democrats. Flip the three Democrat wins, and the House is split 67-67, requiring some sort of power-sharing agreement. The Minnesota State Senate is already controlled by the Republicans, so the stakes in being able to serve as a check on the state’s Democratic statewide officeholders, including the execrable Attorney General Keith Ellison, is considerable.

Each state house district consists of roughly 20,000 voters, so it would take only 1% of the ballots in any of these races to be fraudulently cast using the method described above to potentially swing the race the other way.

The problem is that such fraud would likely be incredibly expensive to detect and virtually impossible to cure. Consider the district where the Democrat won by 40 votes. If only 50 ballots had been mailed out without any ID provided or required, investigators would have to go investigate each and every of those ballots, and prove that there was something amiss. The manpower and time alone would be prohibitively expensive, and would be multiplied by at least a factor of 4 for the other three districts in question.

What’s more, once the ballot is separated from the envelope, there isn’t (or shouldn’t be) any way of reconnecting the two. If there were, it would mean that a sufficiently motivated election worker with access to the ballots and envelopes would be able to find out how any given voter had voted.

Does this mean that the Democrats necessarily retained control of the Minnesota House of Representatives fraudulently? Of course not. It does mean that it’s at least plausible, and demonstrates the extreme difficulty of dealing with fraud after-the-fact. It renders facile claims of fraud-free elections ludicrous, and it increases the chance that someone will try something like this in the future. And allowing this kind of loophole to exist is what damages the credibility of the election system, not those of us calling it out.