Archive for October 22nd, 2017

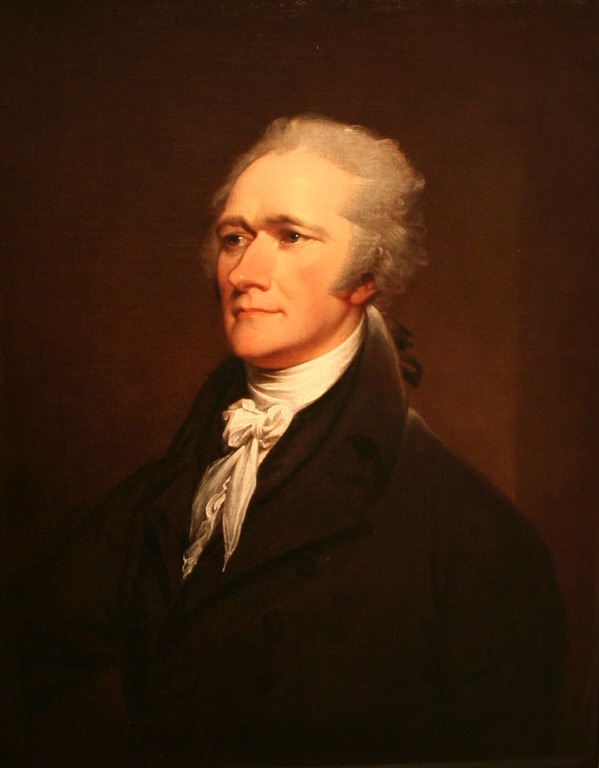

Hamilton’s Productivity

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 22nd, 2017

In his biography of Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow marvels several times of Hamilton’s capacity for work. He wrote the bulk of the Federalist Papers, sometimes turning out as many as 5 in a week. When his opponents in Congress wanted to try to hang him on unfounded corruption charges, for instance, they demanded that he produce voluminous reports on short deadlines. They underestimated him. On p. 250, Chernow describes how Hamilton was able to do this:

Hamilton’s mind always worked with preternatural speed. His collected papers are so stupefying in length that it is hard to believe that one man created them in fewer than five decades. Words were his chief weapons, and his account books are crammed with purchases for thousands of quills, parchments, penknives, slate pencils, reams of foolscap, and wax. His papers show that, Mozart-like, he could transpose complex thoughts onto paper with few revisions. At other times, he tinkered with the prose but generally did not alter the logical progression of his thought. He wrote with the speed of a beautifully organized mind that digested ideas thoroughly, slotted them into appropriate pigeonholes, then regurgitated them at will.

Both the organized mind and the regurgitation are harder than they look. They both require patience, training, and discipline. Yes, he was writing at a different time, when repeating arguments didn’t mean chewing up half of your allotted 700 words. Length was never an issue, and Hamilton, being Hamilton, was brilliant enough that neither was publication or readership. But I notice it when favorite columnists of mine no longer have anything new to say, and part of my own lack of production is from a desire to say something new each time, rather than even mentally cut-and-paste from previous efforts. Contrary to popular opinion, it takes patience to repeat yourself.

This goes hand-in-hand with having an organized mind. One wants to be able to assimilate events and ideas, and to respond to them. But there’s a concomitant risk of building a system and fitting everything into that system. One’s thinking becomes rigid, rather than supple and responsive. You see this all the time with people who reduce all political arguments to one or a handful of principles – everything becomes confirmation of those few underlying ideas, but then all arguments return to those same few ideas. Discussions become stale, because it’s more comfortable to have the discussion you’re used to having.