Archive for category PERA

More Pension Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on May 29th, 2011

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that pensions are moving more money back into hedge funds:

Also, pension officials are using the historically strong returns of hedge funds to justify a rosier future outlook for their investment returns. By generating more gains from their investments, pension funds can avoid the politically unpalatable position of having to raise more money via higher taxes or bigger contributions from employees or reducing benefits for the current or future retirees.

The Fire & Police Pension Association of Colorado, which manages roughly $3.5 billion, now has 11% of its portfolio allocated to hedge funds after having no cash invested in these funds at the start of the year.

…

While pensions have been investing in private equity and what are called alternative investments for many years, hedge funds have represented a smaller part of their portfolio. The average hedge-fund allocation among public pensions has increased to 6.8% this year, from 6.5% for 2010 and 3.6% in 2007, according to data-tracker Preqin. (Emphasis added.)

PERA’s own investments in hedge funds are unclear from the latest data, but if the “Other of Other” category is representative, it could be about 10% of their holdings.

This may be good in the short run. There’s no doubt that some of these funds have done well, being able to hedge some of their risk away and focus on capturing industry or sector returns. But there are some serious dangers here, and they are complicated by the problems already noted with pension accounting.

First, there’s no such thing as risk-free alpha. Remember, the market tries to match risk with return. If someone is selling an investment with 10% return and the risk associated with equities, beware. Because if that were possible over the long run, enough people would pull money from equities and pile it into this mythical investment, so the returns would match. Either that, or there’s hidden risk in there that justifies the extra return.

Either way, in the long run, the funds are taking on more risk, or will have the additional return arbitraged away as more people invest in these strategies. Also, if many of the funds are using the same strategy, it may be difficult for them to execute trades that actually allow them to limit risk, as they may all be trying to sell overperformers, or buy hedges, at the same time.

Another threat to pension funds is in the bolded sentence above. Managers are not only using these returns to justify higher projected returns. What goes unstated is that they’ll also use them to justify the higher discount rates, that make their pensions look better-funded than they are. It’s a perfect example of the perverse accounting incentives built into fund management.

Last, these strategies are not necessarily transparent, making it difficult for independent auditors to even assess the risk that these pensions are taking on.

I’m all for finding ways to hedge away risk, and there’s no reason that pension funds can’t participate in some of those techniques. I’m skeptical that, in the absence of fixing the underlying problems, this approach is going to do any more than paper over problems, yet again.

PERA’s Portfolio Allocations

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on May 23rd, 2011

In yesterday’s Denver Post, PERA’s Chief Investment Officer, Jennifer Paquetteis, responded to an op-ed by investment professional Blaine Rollins (“Hope Is Not An Investment Strategy“) that detailed the risk that PERA has taken on:

PERA has instead relied on solid investment strategies created under the direction of the board of trustees with the help of highly experienced staff and consultants. PERA’s investment strategies match its mission, with an investment horizon of decades and a focus on maintaining the stability of the fund.

…

These investment returns allow PERA to provide reasonable benefits for public servants without placing an excessive burden on taxpayers.

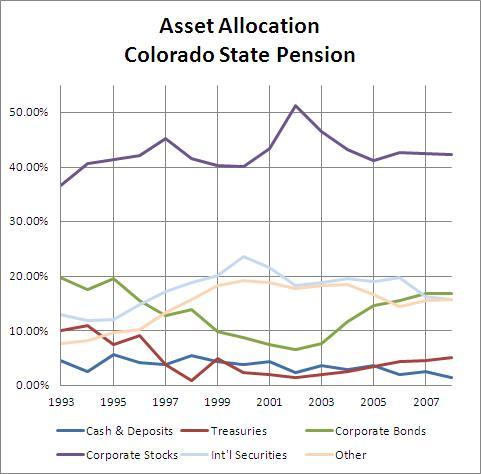

In a previous post, I noted that as a whole, US government pensions had shifted to taking on more risk over time. Interestingly, this does not appear to be the case with PERA:

Seeing that stocks, as they appreciated in 2002, were becoming a disproportionately large share of the portfolio, managers shifted those investments to corporate bonds, which tend to have lower yields, but generally assume less risk. They have also – albeit slowly – grown the proportion of their investment in Treasuries. While I believe that PERA’s overall investment mix still has entirely too much risk built in, it is hard to argue that they have gone around chasing higher yields, or allowed their asset allocation to get out of whack when one class outperformed the others.

The problem is, Ms. Paquetteis’s conclusions don’t necessarily follow from her premises, especially over the long term. Paquetteis’s response only addresses whether or not PERA is following reasonable portfolio diversification techniques. It fails to address the underlying problems with those techniques: the large unfunded liability, the added year-to-year risk associated with needing larger and larger returns, and the faulty accounting standards that not only permit, but actively encourage taking on that extra risk.

Pension Legislation in Congress

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on May 9th, 2011

Kudos to State Treasurer Walker Stapleton for testifying before Congress in favor of H.R. 567, Rep. Devin Nunes‘s Public Employee Transparency Act, which would require states to use reasonable rates of return when calculating the financials for their pension plans, and would also require that they use proper discount rates based on US Treasuries, rather than their rates of return, when reporting their level of fundedness.

States would be able to continue reporting under the old standards, if they chose (and would likely continue doing so anyway), but would be required to issue a second set of numbers using proper accounting standards. States that failed to do so would no longer be able to issue tax-exempt municipal debt, forcing them to use pay higher interest rates and making borrowing more difficult. While the Wall Street Journal is reporting that Congress may yank that exemption altogether, blunting the effect of Nunes’s bill, I rather doubt that would pass the House this year.

For those interested in a fine synopsis of the state pension mess we’re in nationally, I can’t do better than to recommend Josh Barro’s piece in National Affairs, “Dodging the Pension Disaster,” which lays out the problems and potential solutions as clearly as I’ve seen anywhere:

First, pension reforms should include all benefits that will be accrued in the future, not just benefits that will be accrued by new hires. As mentioned earlier, most states are limiting their pension reforms to new employees only — which means they are likely dooming their reforms to failure….

Second, serious pension-reform plans should abandon the defined-benefit model. Three states — Michigan, Alaska, and Utah — have enacted reforms that will move many employees to defined-contribution retirement plans, or at least to sharply modified defined-benefit plans that shift most investment risk away from taxpayers. In most states, however, pension reform has been a matter of tinkering: increasing employee contributions, adjusting benefit formulas, raising retirement ages, and so on….

Third, states should consider voluntary buyouts of existing pension benefits. The two reform principles outlined above address only the costs of pension benefits going forward; they do not help resolve the very real problems associated with states’ existing pension liabilities — those that were incurred by governments as payment for labor that employees provided in the past. Here, there are no easy policy maneuvers: Short of defaulting on these debts, the only way states can eliminate unfunded pension liabilities is to fund them.

That last would be hard for Colorado to consider, as the State Constitution prohibits issuing general obligation debt, but it remains an option for other states.

We should be under no illusions that Harry Reid of Chuck Schumer would even allow Nunes’s bill to come up for a vote in the Senate. But as we know, putting these things out there in the form of legislation is critical to getting actual reform in the long run. And in this case, the long run is shorter than we think.

Public Pensions and Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on April 29th, 2011

In a couple of previous posts, I’ve discussed the folly of using a loophole in public pension accounting to increase the discount rate by taking on added risk. Naturally, that fear would be more justified if it turned out that public pensions were doing that. Herewith, the evidence.

The Census Bureau does an annual survey of the state of public pensions, although they tend to take their sweet time posting the data. (The most recent data available was for FY2008.) Since the time when online records begin, in 1993, until 2008, you can see some obvious trends in public pension funds’ asset allocation:

The proportion in US stocks had risen almost 5 percentage points, from 34% to 39%, and the amount in safer, but really boring Treasuries has dropped from almost 20% to just under 5%. You can see where the poor years for stocks in 2007 and 2008 took back some of their gains, but inasmuch as the fund managers should have been rebalancing, this hardly vindicates them.

The fund managers have also been risking more of their money; cash and liquid securities dropped from about 7.5% to under 3%, although that could be for a number of reasons. The pension operations could be efficient, for instance, or the managers may have had better actuarial data at their disposal. In what looks like a gap in the Census survey questionnaire, “Other” is up significantly, from 5% in 1994 to 13% in 2008. Anything that’s 1/8 of your investment portfolio shouldn’t really be lumped together as “Other.”

And since its introduction as a separate category in 2002, Foreign Investments (not shown) have risen from 12% to about 15%. That’s probably a result of both better returns and increased investment.

I also want to emphasize that this is aggregate data for State & Local pensions across the US, not just for PERA. CalPers may well distort the data, and some plans, like DERP, are around 90% funded and suffered very little in the stock downturn in terms of fundedness.

In any event, what is clear is that the instruments best-suited to stable, long-term returns (at least up until now), US Treasuries have either been sold off or allowed to mature, with the funds being put into US stocks and some other, almost certainly riskier, categories.

There’s a lot more data over at the Census site, including some state-only data over the last 3 years that also has actuarials associated with it, so I’m hoping to make some time to dig into that, as well, but as usual, no promises.

Everybody Likes A Good Discount

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on April 24th, 2011

So with all the discussion about PERA, one key aspect of pension accounting hasn’t yet been mentioned: the discount rate. Now before you go all accounting-comatose on me, understand how important this is. Because with all the talk of how underfunded PERA is, it’s actually even more underfunded than you think.

Basically, if you have an obligation to meet, the discount rate is the rate you use to see how much money you need to have now in order to meet that obligation. So if you’re going to have to make good on a $100,000 obligation 10 years from now, and you use a 4.5% discount rate, you need to have about $65,000 now. If you use an 8% discount rate, you only need about $46,000.

Of course, the discount rate isn’t arbitrary. It represents a concept. The discount rate is the required rate of return, the return that an investor in that project requires, given the level of risk that he’s taking on.

The problem here, and how this relates to PERA (and many, many other public pensions), is that PERA is using the wrong discount rate. Instead of using the 4.5% discount rate, they’re using the 8% discount rate, which makes them look even less underfunded than they are.

PERA – Why 8% Isn’t 8%

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on April 22nd, 2011

State Treasurer Walker Stapleton has been on the hustings, touting the need for PERA reform. His oped in the Denver Post a little while ago pointed out that the fund’s actuaries assume an 8% return on investments. If we don’t do something about the underfunding, Stapleton noted, we’ll be forced to take on more risk to try to reach the fund’s investment goals.

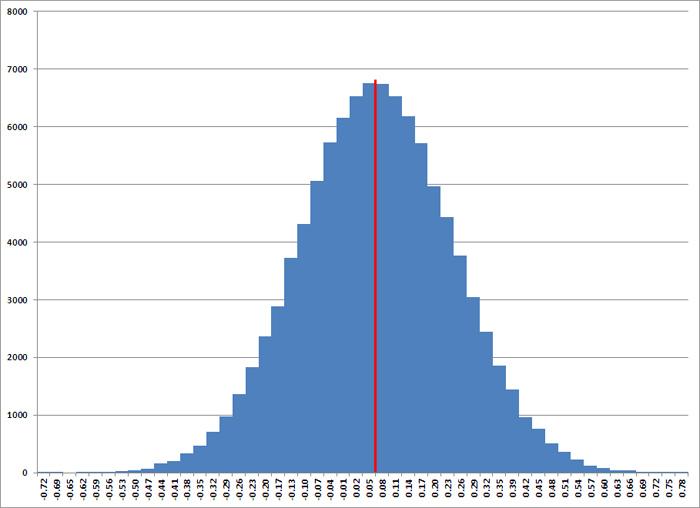

Now, PERA’s been criticized for assuming an 8% return, but that’s not really the problem. Eight percent is, in fact, the average annual return on US stocks since about 1870, according to data collected by Robert Shiller, he of the half-eponymous Case-Shiller Housing Index. The problem is, the standard deviation – the range within which about 5/8 of the returns actually fall – is 18%:

Which means that a lot of the time – almost one-third – you’re getting negative returns. For Backbone Business, I worked up a little scenario where you’re starting with $100,000, paying out certain portion each year, getting 8% return a year on your balance, and you come out even. But what should be apparent is that there are lots of scenarios that get you 8% average return, but force you to pay out more than you’re getting in the early years, and you never make up the difference. Here are some very basic scenarios:

And the graphs of the balances:

Circular Logic on Gov’t Pensions

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, PERA, PPC on April 5th, 2011

In this morning’s Denver Post editorial, explaining why government employees should only temporarily be asked to take more partial responsibility for their own retirement, comes this remarkable claim:

But it shouldn’t be a long-term fix. Shifting the makeup of the pension funds could adversely affect the financial soundness of PERA.

That’s because employee and employer contributions are treated differently. The money that employees put in the system goes with them if they leave the system. If the fund mix gets too out of whack, it could be a financial problem.

This is a classic example of thinking inside the fiscal box they’ve put the rest of us in. These pensions – the ones in question – are defined benefit plans. As has been pointed out in a number of places this morning, Colorado is uncommonly generous with the percentage of an employee’s income it tries to replace in pensions.

At a minimum, shouldn’t that obligation be either contingent on the employee leaving his money with the plan? If not, if they have the right to take that money with them, then ought not the pension plan’s obligation be reduced, proportional to the amount funded by the employee? If it’s the employee’s money, then, well, it’s the employee’s money, and if they want to be responsible for investing half of their retirement money on their own, then they should live with the consequences of that. It certainly doesn’t make any sense for the plan to have to shoulder more of the burden for an employee who leaves before retirement.

The real problem here is that it’s a defined obligation plan in the first place, and that it’s less than fully-funded. If the plan were fully-funded, if every dollar of future obligation were already invested for, then this wouldn’t be a problem. It’s complicated by the fact that none of these plans is fully-funded, so all of them rely on current contributions to pay current obligations, rather than socking that money away under the account for the individual.

It’s a result of lousy accounting having had a meet cute with lousy political incentives starting about 10 years ago. It’s no longer sustainable, and eventually we’re going to have to convert all of these plans over to defined benefit plans. If we can’t do that in one fell swoop, we can at least start by having public employees permanently assume a greater responsibility for their own retirement.

Business-Friendly?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on January 14th, 2011

Governor Hickenlooper (and boy, that need to be in the editor clipboard) has signalled a desire to be more “pro-business.” There’s a reason for that:

It’s already bad enough that the US has the highest corporate tax rates in the industrialized world. We also know that jobs tend to flow from blue states to red ones, and Colorado has a lot of red states surrounding it.

Kim Strassel has a fine piece in today’s Wall Street Journal about how the red-state governors of Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Ohio are already taking advantage of Illinois’s addiction to self-destructive behavior by luring businesses away. There are some limits; it’s

unlikely that Gary, Indiana, a joke since Meredith Wilson’s time, will be able to replicate Chicago’s freight infrastructure. But there’s no good reason why businesses can’t relocate to Salt Lake City, Cheyenne, Santa Fe, or Texas. (Cheyenne, you say? Well, yes. It made news last year when a large computer server farm, dedicated to some environmental purpose or another, relocated there to get away from Colorado’s high electricity rates.) Minnesota also isn’t so far away, and the new Republican majority up there may be enough to override Governor Dayton’s apparent intent to fumble this opportunity for his state.

Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, and Texas all rank higher on the Tax Foundation’s Business Tax Climate Rankings (http://www.taxfoundation.org/taxdata/show/22661.html). Nevada could be a nice stop for Californians looking to defect. The aforementioned Minnesota ranks 43rd, another reason they could be looking to improve.

And remember that “business-friendly” doesn’t necessarily mean “market-friendly,” or “growth-friendly.” Success at nurturing large businesses could come at the expense of small ones, which may or may not be more mobile. The hunger to lure larger defectors from California could mean subsidies at the expense of the rest of us.

Mayor Hickenlooper has already succeeded in driving business out of Denver to the surrounding cities, through software taxes, the head tax, and regulatory snarl. He’ll face similar pressures from his base to repeat that performance as governor. Let’s hope he realizes that other states will be willing to capitalize on that error.

Public Pensions, Public Purse

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, HD-6 2010, PERA on October 21st, 2010

On the campaign trail, I’ve spoken to any number of public employees and retirees who are worried about PERA, understand the problems, and who recognize the system needs to be changed. Some retirees are even willing to take cuts themselves, although I think asking them to do so would be a breach of faith. Employees and even reitrees are clearly more flexible on this issue than their unions are. To his credit, Mayor Hickenlooper has proposed changes to Denver’s pensions to try to make it more solvent:

For future employees only, the proposal would increase the minimum retirement age from 55 to 60, further decrease the pensions of those who retire early and increase the time required for vesting from five years to seven years….

This year, city workers had to contribute an extra 2 percent of their paychecks to offset losses in the pension fund’s investments…The most recent analysis shows the pension plan ended December 2009 with 88.4 percent of its obligations funded, better than many other public pension plans, including the one for state workers.

Now, an 88.4% funded status is excellent, especially given the status of other public pensions. It speaks well of the conservative management of plan assets, although it’s worth noting that Denver may be using the expected return as the discount rate, rather than the level of obligation, which would overstate the plan’s funded status. (Full disclosure: I’m friends with Steve Hutt, who attends my synagogue, and haven’t had a chance to ask him what discount rate the plan uses.)

Nevertheless, defined benefit plans will almost always encounter, over their lifetimes, a rough patch rough enough to make them insolvent without greater contributions. The Mayor’s efforts are better than doing nothing, but will face opposition in the City Council from unions, and don’t address the fundamental problem of making promises the city can’t keep.

This is important, because dealing with PERA will be an important job of the next governor and legislature. According to Business Insider, Colorado’s pension fund is only 12 years away from actual insolvency, 8th-worst in the country. Unless we deal with this, by getting obligations to current and imminent retirees fully funded, and then converting to a defined contribution plan for new and younger state employees, we will end up bankrupting the state. Pension obligations – backed by unions whose greed is not representative of their members – will eat us alive, leaving almost nothing for actual services and functions.

I’m not sure that John Hickenlooper is willing to make that decision, but I am certain that the current legislative majority isn’t. We need to elect one that is.

House Republicans’ Platform – Jobs

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, HD-6 2010, PERA on September 27th, 2010

One of my biggest concerns regarding the impending state House elections was that we, as a party, might end up running without much of a platform beyond, “We’re not them.” Now, this year, “We’re not them” probably would be enough to get us the six seats we needed for the majority. But it’s not really much of a governing mandate. Had this happened, we’d have been running the risk of repeating the same mistake we’ve just lived through with the Democrats, who took a “We’re not Bush” vote to be a mandate to remake the country into Sweden, and are now looking at their worst electoral performance in generations.

You’ll note that I’m using the pluperfect subjunctive, which means that this didn’t happen. Today, the House Republicans issued a four-part governance plan, dealing with Fiscal Issues, Jobs, the Economy, and PERA. I’ll be rolling these out over the next couple of days, along with my own commentary on them. Let’s start with the one that’s the most important to Coloradoans – Jobs

Everyone knows the numbers: we’ve lost 160,000 jobs since the beginning of 2008. Our state unemployment rate hit 8% in 2010, double from three years earlier. The only way we’re going to get those jobs back is to create incentives for business, and by growing the private sector. There are no easy fixes here, but Colorado can make use of its world-class research facilities, and it can draw on its tremendously well-educated workforce. There are also long-term strategies, and short-term jump-starts.

- Incentivize large-scale business investment in manufacturing, aerospace and other high-wage sectors by revisiting the Business Personal Property Tax.

It’s important to do this this year, when the deficit is relatively low (“relatively,” in this case, meaning a couple hundred million dollars), to give the jobs time to materialize, so that they’ll be around when the federal money disappears in 2011-2012.

- Constructing and maintaining a cutting edge multi-modal transportation system is essential to a thriving economy. Policymakers must create an infrastructure strategy for the state, seeking lower cost solutions and opportunities for public-private partnerships.

Not such a big fan of “multi-modal,” as it usually means, “expensive, inflexible, under-used rail.” But it could also mean, “flexible, privately-operated buses and cars.” This could mean privately-operated toll roads, which have worked extremely well in other places.

- Improve the state commitment to biotechnology and biosciences by building on a 2008 package that provided some $26 million assistance for Colorado start-up companies8 and research institutions seeking to commercialize new technology.

- Work with Colorado’s universities in technology transfer opportunities, to create new Colorado jobs and companies. Identify reasonable solutions to obstacles which stop cooperation between academic research institutions and free enterprise.

I’d include “nano-tech,” which will change the world, in this list, but that’s a quibble. Productizing this stuff is really the name of the game; it lowers costs, raises our standard of living, creates both fabrication and design jobs, meaning it can employ both skilled workers and PhDs. It creates the potential to raise our exports from the state, which haven’t kept pace with those from other states. In the best-case, it can turn Colorado into another Silicon Valley-type operation, assuming it can find and attract venture capital for these operations.

The co-location of research, industry, and capital is fundamental to truly inventive entrepreneurship, and while it won’t create large-scale employment tomorrow, it’s the kind of thing that will bring back the economy. I’m delighted to see the prospective House leadership embracing it.