Archive for category PERA

Lowering the Hill

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on January 23rd, 2013

Ultimately, large changes will be needed to keep PERA solvent. But little changes can have an effect, too. Today, the state House Finance Committee will be hearing HB13-1040 from Republican Rep. Kevin Priola:

Current law averages the 3 highest annual salaries of a member of the public employees’ retirement association (PERA) when calculating that member’s retirement benefit amount. The bill increases the number of highest annual salaries used from 3 to 7 for anyone who was not a member, inactive member, or retiree of PERA as of December 31, 2013.

In 2010, SB1 changed some rules to make it more difficult for employees to suddenly spike their salaries and other compensation at the ends of their careers, in order to game the system and maximize their PERA benefits. For instance, for benefit calculation purposes, raises and other increases in compensation – like saved vacation being cashed in – were limited to 8% in any given year. Employees could receive larger raises, but benefits could only be calculated on the first 8% of the increase.

This bill would make it even harder to game the system by averaging the highest seven years’ compensation instead of the highest three. It’s a reasonable measure, and it would only apply to employees who join PERA after the end of this year. The Democrats enjoy a large majority on the Finance Committee, so they may well kill the bill. But the fact that it got assigned to the Finance Committee at all, rather than relegated like SB13-055 to the State, Veterans, and Military Affairs Committee, makes the outcome less certain.

Democrat Sen. John Morse Follows Familiar Pattern On PERA Reform

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on January 23rd, 2013

The state Democrats, led by State Senate President John Morse (D-Colorado Springs), are continuing their deeply unserious approach to Colorado’s massive unfunded PERA liability this session. Incoming Speaker of the House Mark Ferrandino (D-Denver) had already indicated as much, first by characterizing those who would seek to deal with the problem as wanting to use the economic situation as an excuse to take away public employee’s pensions, and then by appointing Lois Court (D-Denver) as Chairman of the House Finance Committee.

The latest sign comes with respect to a bill proposed by Republicans Sen. Kent Lambert of Colorado Springs and Rep. Lori Saine, a freshman Republican from Dacono. The bill, SB13-055, would require PERA to use the state’s long-term borrowing interest rate as the discount rate for its liability, and would require that the CAFR be released by May 31 of each year. It would also require that contribution and/or benefit levels for any individual fund be adjusted when the amortization period for that fund climbs beyond 30 years.

All of these are eminently reasonable proposals. For reasons discussed before, the discount rate should be the required rate of return of PERA’s investors, the members. There is also no real reason why PERA can’t produce a CAFR within five months of the end of the calendar year; those dates have been slipping in recent years, but the fact is, the bulk of the CAFR is boilerplate or easily-written text, and the same financial statements and charts each year. And since the stated goal of PERA is to be within a 30-year amortization window, requiring them to be so would simply put teeth into an existing target.

Yet Sen. Morse has chosen to assign the bill not to the Senate Finance Committee, which has jurisdiction over PERA oversight, but to the State, Veterans, and Military Affairs Committee. That committee, often referred to as the “kill committee,” is traditionally staffed with the most partisan members of both parties, and used to kill inconvenient bills. Often that’s because “no” votes on the bills might be embarrassing to the majority, perhaps sufficiently embarrassing that some members wouldn’t be able to resist the temptation to vote for them.

That Senate President Morse has chosen to put this bill in front of the kill committee is practically an admission of its common sense, and his lack of it, but it does make clear the two halves of the Democrats’ full-court defense of their public employee clients’ pension plans.

First, they’ll protect them from any votes they might lose, and also protect the House and Senate Finance Committee members from having to cast “No” votes they’ll later have to explain.

Second, both Ferrandino and Morse have claimed that 2010’s SB1 “solved” the PERA problem for good, though tremendous liabilities remain, even given the plan’s own overly-optimistic assumptions and accounting practices. That will be their explanation for dodging these votes, but even if true, it’s a non sequitur. If PERA is truly fixed, surely members of the committee charged with its oversight would not only be the best-informed of that fact, but also best able to explain it to constituents. Putting the bill in front of a committee whose actual charter has nothing whatsoever to do with PERA, and whose reputation is one of chief enforcer, can’t inspire much confidence that the Democrats will be dealing with the state’s financial problems in good faith in the next two years.

The Hill Gets A Very Little Less Steep – For Now

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, PPC on January 22nd, 2013

One of the main points of contention about PERA has been the expected rate of return. Up to 2001, PERA used an expected rate of return of 8.75%, but lowered that to 8.5% from 2002-08, and again to 8% in 2009, where it now stands.

So how has PERA done since 2001, when it stood at a 100% funding level? The chart below shows the annual return over those 11 years for which they’ve reported, plus an estimated return based on a similar portfolio from CalPERS, the California pension plan. CalPERS has a .99 correlation with PERA, which is about as close to metaphysical certainty as anything human gets. In 2012, CalPERS reported a 13.26% return, which would project a 13.9% return from PERA, so just for grins, I’ve plugged that into the 2012 spot.

The red line is the running CAGR from 2001, or Cumulative Average Growth Rate for 2001 through the current year.

As you can see, over time the red line becomes less volatile, as more years are factored into the average.

The green and purple lines are where it gets interesting. Those lines are the return that PERA would have to see over the remainder of the 30-year window from 2001-2030, in order to meet the 8.75% and 8% targets. So, for instance, after 2007, in order to have a CAGR of 8.75% from 2001-2030, PERA would have to have returns of 9.3% from 2008-2030.

Note that using the 8% return from 2001 basically gives hindsight credit to PERA, since in 2001 they were projecting 8.75%, not 8%. Let’s blow up that part:

As you can see, PERA started out with poor 2001 and 2002 returns, which put it in an immediate hole. Even good returns from 2003-2007 only got the required returns down to 9.3% and 8.3%, respectively. Then 2008 happened. By now, we’re 12 years into that 30-year window, and even a good year like 2012 will only push the required return down a little bit, about 0.3%. For instance, it would take 7 years of 15% returns to get the required return for the 8.75% line down to below 8.75%, in effect, to catch up to the 8.75% projection, and it would take 5 more years to catch up to the 8% projection. It’s highly unlikely that even 5 years will pass without a normal, cyclical recession, and attendant lower returns.

The average return is 6.28%, the CAGR is lower, just over 5%. In fact, any set of returns with an average of 8%, but which are not actually 8% each year, will compound to less than 8%, making it that much harder to make up ground. Bear that in mind when someone talks about how easy it is to make up for a couple of bad years.

All of this argues for using a Monte Carlo simulation to determine solvency, rather than a simple rate of return. Such a model is a little more expensive to run, but will give a far more accurate picture of the health, or lack thereof, of any defined benefit plan.

PERA – It’s All For The Kids

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Education, PERA, PPC on January 20th, 2013

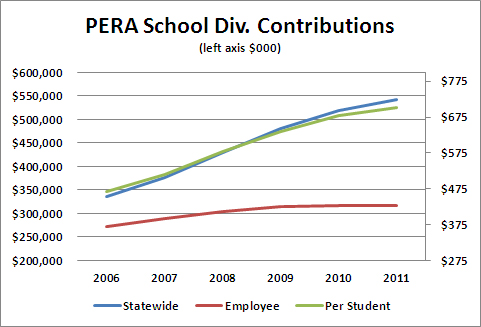

Not all school spending is for the kids. A lot of it is for the teachers, at the expense of the kids. Over the last five years, even as school districts and teachers unions complain that per-student spending has been “slashed,” “cut to the bone,” or “eviscerated,” per-student spending on the PERA School Division has been growing well beyond inflation. Here are the per-student contributions by the major local school districts (minus Denver, which has its own PERA division), and statewide:

Over the least 5 years, this has translated to growth rates well in excess of inflation:

And who’s been picking up the tab? The Employer contribution has been growing far in excess of the Employee contribution in absolute terms. The employer contribution has been growing at 10% per year from 2006-2011, while the Employee contribution has grown at a 3% rate over the same period. The overall per-student increase has been just under 8.5%.

Not only is PERA taking money from the classroom, it’s taking taxpayer dollars from the classroom at a wildly disproportionate rate. Is this what the teachers unions mean by “shared sacrifice?”

PERA’s Resolute Optimism, Part 2

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 9th, 2012

In the previous post, I mentioned that PERA, in retaining its 8% expected rate of return, was persisting in an unwarranted optimism, one that is likely to end up costing the citizens of Colorado billions of dollars down the line. Part of the evidence was that other municipal pension plans around the nation have recently lowered their expected rates of return. That said, as of 2009, the overwhelming number of plans in the Center for Retirement Research’s Public Plans database were living in what can only be described as Fantasyland, as the following histogram shows:

I’m sure the right part of the graph, which resembles a strong signal from those plans to their taxpayers footing the bills, is only accidental.

In fact, between 2001 and 2009, plans were extremely reluctant to revise their expected rates of return, despite the fact that they rarely met them for more than a year at a time, and continued to fall farther behind in their funding. If you look at actual returns for those years, they don’t come anywhere close to what was projected:

The result is that plan assets haven’t kept up at all with plan liabilities, even in these years when the market has performed reasonably well (Source: Public Fund Survey):

Understanding that many factors go into whether a plan’s funded level increases or decreases, the fact is that looking forward from 2001 to 2009, over the succeeding 21 years, the median plan would have to return about 10.5% over the following 21 years, to make up for having fallen behind in the first decade:

The problem, of course, is that plans have spending requirement every year; they can’t simply choose to sit on their assets and wait for their investments to catch up. It means that low returns in early years require even higher returns in the later years for the plans to return to 100% funded levels, without increasing cash infusions or a reduction in benefits.

One guess as to which will be the plans’, the governments’, and the SEIU’s first choice.

PERA’s Resolute Optimism

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 7th, 2012

PERA’s Board recently voted to retain its wildly optimistic expected rate of return of 8% over the next 30 years. The decision has the effect of reducing the unfunded liability twice – once through higher returns, and again because they mistakenly use the rate of return as the discount rate. Remarkably, PERA’s board made that decision even as pension plans all over the country are reducing their expected rates of return.

The latest is the Orange County Employees Retirement System, which called a special meeting for Thursday evening to lower its expected return from 7.75% to 7.25%. It follows CalPERS, CalSTRS, and about 40 others of the 126 public plans in the National Association of State Retirement Administrators’ Public Fund Survey.

The most direct parallel is the change made only Tuesday by the Pennsylvania Municipal Retirement System, which lowered its expected rate of return from 6% to 5.5%, starting January 1. PMRS’s returns closely track those of PERA, returning an annualized 0.5% less per year over the last 10 years than PERA:

That comes to an annualized rate of 5.3% over the last decade for PMRS, or just below their new rate of 5.5%. PERA’s barely done better, and 5.8%, but insists on retain an industry standard, and wildly unrealistic, 8% expected rate of return.

Note that PERA’s average rate of return is 6.9%, while its cumulative average return is 5.8%. Of course, you can’t spend average returns, you can only spend cumulative returns. Yet another reason for PERA to be more, rather than less, conservative.

On the other hand, it must be encouraging to see PERA’s resolute optimism at a time when so many other plans are losing heart.

PERA, Personally

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 5th, 2012

One of the hardest things about discussing PERA’s liability is the sheer magnitude of the numbers involved. Twenty-five billion used to sound like a lot, until we started throwing around trillions. Forty billion, likely closer to the real number, sounds like it might be more, but it’s almost impossible to gauge how much more.

The chart below tries to show how PERA’s unfunded liability has grown in terms of our ability to pay it off. In 2000, PERA was nominally overfunded, meaning that all of its long-term liabilities were accounted for, and then some. In reality, this almost certainly wasn’t the case, but for the purposes of this post, we’ll just use PERA’s own current-dollar estimates of its unfunded liability.

Using BEA numbers for Colorado’s GDP, its total Personal Incomes, and its population, it’s a little easier to see the threatening direction this debt is taking. On a per-person basis, the unfunded liability now sits at just over $4000. That means that, to pay off the unfunded liability, it’s $4000 out of the earnings of the average Coloradoan. This includes those who are too old and too young to work, so for the average worker, the number is much higher. Four thousand dollars may not sound like a lot, but of course, it’s going to get worse – likely, much worse – before it starts to get better.

As a percentage of the state GDP and Personal Income, things are even more discouraging. PERA’s liability amounts to 8.15% of Colorado’s GDP, and nearly 10% of the total Personal Income. But this isn’t the only debt that the state, local, and district governments owe on your behalf, and it’s likely not the only debt you owe, either.

From 2004 to 2007, the ratios appeared to improve, but if you look closely, you’ll see that during a period of strong growth, the per-person dollar liability was flat, and the per-GDP and per-PI percentages barely moved. This strongly suggests that this is a liability that it’s going to be very hard to grow out of.

PERA will be quick to point out that you’re not going to be expected to cough up all of this money at once, and that they have a long-term, 30-year glide path to solvency. Any time any government program says it has a 30-year plan for solvency, you should stop listening and start moving your money someplace else. As we’ve noted before, PERA is significantly understating the size of the unfunded liability, both by overstating the rate of return and by misusing the discount rate. Moreover, mentally amortizing the liability over 30 years makes it that much easier to ignore until someone misses a payment, and the whole structure comes crashing down. I’m sure that San Bernadino and Stockton were using similarly comforting thoughts before they filed for Chapter 13.

Demagoguing PERA

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 3rd, 2012

Just in case anyone thought that the incoming Democrat majority in the Colorado legislature was planning to take a responsible approach to Colorado’s continuing PERA debacle – it has not yet reached the crisis stage – Speaker-to-be Mark Ferrandino has laid those fears to rest. Morningstar has published a report reiterating what anyone with any sense already knew, that PERA is not “fiscally sound,” with a funded ratio of 58%. PERA complains that that only accounts for the state division, and that including other divisions raises the fundedness to 60%. This is the equivalent of a terrible student trying to argue his grade up from an F- to an F.

Ferrandino, instead of understanding that promises are being made that simply cannot be kept, demagogues the issue, claiming that, “There are some who would like to use the economic downturn to take away people’s pensions.” I suppose it’s progress of a sort that he acknowledges that we’re still in an economic downturn, but where on God’s green earth does he think the money comes from to pay those pensions, if not from the retirement savings of the rest of the people in the state? Where is the fairness in using the force of law to place the pension of a 30-year-old government worker ahead of the average Coloradoan’s ability to provide for himself and his family?

Don’t expect much help from the Senate, either, where incoming Senate President John Morse has hired SEIU flack Kjersten Forseth to be his chief of staff.

As California collapses, Colorado has a golden opportunity to pick up businesses looking for more healthy homes. In 2010-11, the Denver metro area had the 7th-highest rate of in-migration from other parts of the country. Unfortunately, the state’s Democrats seem bound and determined to import not California’s prosperity, but its pauperizing policies instead.

Certificates of Prevarication – Part II

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Denver, PERA, PPC on November 27th, 2012

Yesterday, I wrote about the Jefferson County School District’s use of Certificates of Participation to get around the State Constitution’s requirement for a public vote before issuing general obligation debt. I had forgotten that once upon a time, Denver Public Schools did almost exactly the same thing.

The scheme – used widely around the state, and even by the state, is for the district to set up a corporation and then lease its own property back from the corporation, with the lease payments matching bond payment due on debt floated by the corporation in the public debt markets. The debt isn’t exactly unsecured – the school buildings themselves serve as collateral. But there’s no separate revenue stream dedicated to the lease payments, which come instead out of general fund revenue, the very definition of general obligation indebtedness that the constitution seeks to limit.

In 2008, Denver Schools issued$750 million worth of both fixed- and floating-rate COPs, in order to recapitalize its own pension program, which had a $400 million funding gap. This was necessary for PERA to agree to absorb the DPS retirement system. While the ins and outs of the deal are beyond the scope of this post, suffice it to say that by 2010 the deal had become a key element in the Democratic US Senate primary between Andrew Romanoff and Michael Bennet, who had been Denver Schools Superintendent at the time of the COPs.

Our concern here isn’t whether or the the deal was well-structured on its own terms. It may well have been, and has, at any rate, since been refinanced on terms more favorable to the District. The point here is that Denver Public Schools, in order to facilitate turning over the unfunded portion of its own pension plan to the rest of the state, issued what is general obligation debt in all but name in order to cover a shortfall. That debt, issued without public approval, now accounts for 37.6%, or 3/8, of the school district’s entire long-term debt.

In the meantime, the burden of DPS’s unfunded pension liability has been neatly shifted onto the rest of the state. DPS may be required to step in with additional payments if an actuarial analysis shows that, in 30 years, the plan will be less sound than the rest of PERA. As of the 2011 CAFR, the plan’s fundedness had fallen from 88% to 81%, still the least-unhealthy PERA division by far. And the process of renegotiating what is likely to be, as with most public pensions, an unsustainable burden on the taxpayers, got much more complex with the addition of the state and PERA as explicit parties to the contract.

Certificates of Prevarication

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA on November 26th, 2012

I’ve already written about the Jefferson County School Board’s decision to default on its Supplemental Pension Plan. It turns out it’s also using something called Certificates of Participation as a loophole to circumvent the State Constitution’s ban on governments issuing general obligation debt without a vote of the people. They’re not alone in this, and it can lead to a significant understatement of a government’s – thus the citizens’ – total indebtedness.

In 2006, the JeffCo School Board voted to offer teachers the option of taking a lump-sum payment for the value of their pension benefit, or to stay in the 10-year payout program. In order to help capitalize the buyout, the Board issued $38.7 million worth of Certificates of Participation (COPs), with maturity dates from 2007 to 2026.

Note that even if the Board succeeds in closing down the Supplemental Retirement Program and discharging itself of about $7.4 million of unfunded obligations, approximately $33.1 million worth of principle on those COPs will remain on the books.

Since the State Constitution prohibits governmental entities from issuing unsecured debt without a vote of the citizens, how is such a this possible?

Keep your eye on the shell with the pea.

Technically, the COPs weren’t issued by the School District, but by a corporation, the Jefferson County School Finance Corporation. Nine school building were leased by the District to the Corporation for some nominal amount, and then leased back to the District by the Corporation. The lease payments by the District to the Corporation are designed to match the bond payments due by the Corporation.

The bonds are therefore secured by the revenue stream provided to the Corporation by the lease payments from the District. What shows up on the financial statements of the District aren’t the COPs, but the lease payments, which are budgeted annually, not as a formal, long-term commitment.

Investors, of course, are not fooled by this. The entire term of the lease shows up on District’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) as a Capital Lease, as a long-term obligation (see Note 10, p. 66), not just the next year’s payment. They show up directly, as “Certificates of Participation” on the District’s Debt Capacity Schedule 9 (P. 114). If the payments are missed, it will damage the credit rating of the District.

To be fair, JeffCo is far from the only jurisdiction to use this mechanism to get around the ban on general obligation debt. Denver City Council used a similar mechanism to launder its own obligations that it incurred when it backed debt for the Union Station redevelopment project, in order to secure federal funding. This appears to be a legal means of side-stepping the constitutional limitation.

The State Constitution recognizes the danger inherent in debt, which is why bond issues need to be approved. If investors don’t treat the Corporation as a separate entity from the District in evaluating creditworthiness, why should the state?

Note:

Here is the relevant paragraph from the debt issuance, describing the shell game, and showing that it specifically contemplates the ban on general obligation debt and is designed to avoid it (emphasis in original):

Neither the Lease nor the Certificates constitutes a general obligation indebtedness or a multiple-fiscal year direct or indirect debt or other financial obligation whatsoever of the District within the meaning of any constitutional or statutory debt limitation. Neither the Lease, the Indenture nor the Certificate have directly or indirectly obligated the District to make any payments beyond those appropriated for any Fiscal Year in which the Lease shall be in effect. Except to the extent payable from the proceeds of the sale of the Certificates and income from the investment thereof, from Net Proceeds of certain insurance policies and condemnation awards, from Net Proceeds of the subleasing of or a liquidation of the Trustee’s interest in the Leased Property or from other amounts made available under the Indenture, the Certificates will be payable during the Lease Term solely from Base Rentals to be paid by the District under the Lease. All payment obligations of the District under the Lease, including, without limitation, the obligation of the District to pay Base Rentals, are from year to year only and do not constitute a mandatory payment obligation of the District in any Fiscal Year beyond a Fiscal Year in which the Lease shall be in effect. The Lease is subject to annual renewal at the option of the District and will be terminated upon occurrence of an Event of Nonappropriation or Event of Default. In such event, all payments from the District under the Lease will terminate, and the Certificates and the interest thereon will be payable from certain moneys, if any, held by the Trustee under the Indenture, any amounts paid under the policy of insurance, and any moneys available by action of the Trustee regarding the Leased Property. The Corporation has no obligation to make any payments on the Certificates.