That, apparently, is the philosophy behind the Democrats’ bill, HB-1408, for eviscerating the rules concerning Congressional redistricting. Next year, after the 2010 Census and elections, Colorado will, like every other state, draw new congressional district boundaries. In the past, with one notable exception I’ll discuss below, there have been certain statutory rules governing the drawing of those boundaries, describing what criteria the courts may or may not take into consideration. The Democrats’ bill would seek to repeal all of these statutory guidelines and replace them with..nothing.

In general courts could not use “non-neutral” factors such as “political party registration, political party election performance, and other factors that invite the court to speculate about the outcome of an election.”

Here are the “neutral” factors that courts could use, according to the relevant statute:

(I) First, a good faith effort to achieve precise mathematical population equality between districts, justifying each variance, no matter how small, as required by the constitution of the United States. Each district shall consist of contiguous whole general election precincts. Districts shall not overlap.

(II) Second, compliance with the federal “Voting Rights Act of 1965”, in particular 42 U.S.C. sec. 1973;

(III) Third, except when necessary to comply with subparagraph (I) or (II) of this paragraph (b), political subdivisions such as counties, cities, and towns shall be preserved intact and shall not be fragmented or dispersed across district lines. When applying this criterion, preservation of the most populous counties, cities, and towns shall take precedence. When county, city, or town boundaries are changed, adjustments, if any, in districts shall be as prescribed by law.

(IV) Fourth, communities of interest, including ethnic, cultural, economic, trade area, geographic, and demographic factors, shall be preserved within a single district whenever possible. Traditional communities of interest in Colorado include the western slope and the eastern plains.

(V) Fifth, each congressional district shall be as compact in area as possible, and the aggregate linear distance of all district boundaries shall be as short as possible; and

(VI) Sixth, disruption of prior district lines shall be minimized.

Presumably, the Voting Rights Act would continue to apply, and despite the failure to capitalize “Constitution,” one assumes that the Democrats don’t want to introduce wild disparities in district populations. The courts will still be bound by federal law in drawing federal districts. Those details aside, there are good, longstanding reasons for all of these exclusions and inclusions.

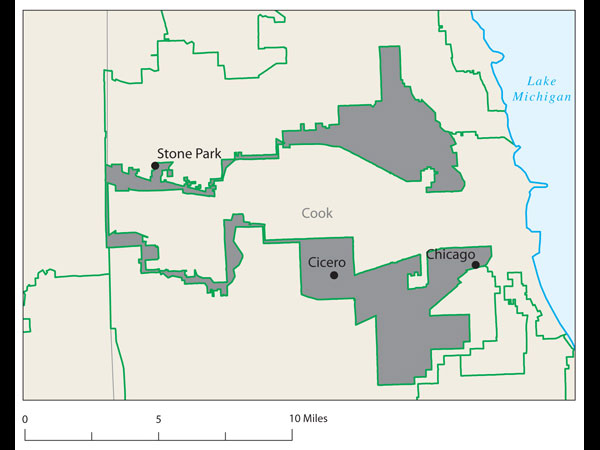

The absence of the additional restrictions would open the door to the sort of gerrymandering that characterizes Illinois:

It also makes intuitive sense that cities and towns should have the same Congressional representation, where possible. In fact, they are merely a subset of (IV): communities of interest. It makes sense that interests, rather than parties, should be represented is legislatures. Citizens have interests. They may be economic, ethnic, cultural, or social, but citizens are far more likely to think about them on a daily basis than they are to think about their party affiliation, if any. Political parties may or may not be an expression of those interests, but are, at best, a secondary overlay on top of them. If this weren’t true, “Unaffiliated” wouldn’t be our largest party non-identification in Colorado.

This may be a perfectly logical choice, for a party that sees interests as tools of political power, rather than parties as expressions of coalitions of interests, but I doubt that most people think that way.

But aside from the philosophy involved, it’s important not to lose sight of the mechanics. Redistricting in Colorado is done by a tripartate commission from each of the branches of the government. Two each (one from each party) from the House and Senate, three appointed by the Governor, and the last four appointed by Supreme Court’s Chief Justice. If the commission can’t reach agreement, the District Court can impose a solution, as happened in 2002, when it adopted the Democratic plan for Colorado’s new 7th Congressional district. Interestingly, the court specifically included “competitiveness” in its ruling, despite a specific statutory injunction against using party registration as a criterion. This bill aims to remove even that potential legal obstacle.

HB-1408 is directed to the courts, not the commission, implicitly anticipating gridlock there. If this weren’t the case, the bill would remove any guidelines from the commission, as well. I don’t think it goes too far to suggest that the strategy here is to repeat 2002, obstructing a solution and then getting the courts to adopt a partisan plan.

CORRECTION: I am reminded by Matt Arnold that the reapportionment commission only applies to state legislative districts. Congressional districts are redrawn by the General Assembly alone, without the governor or the courts. Of course, this increases the chances for gridlock, but it also means that the composition of the Supreme Court will be less important in this regard, should this pass. Similarly, it means that the composition of the legislature will be far, far more important.

#1 by yaakovwatkins on April 16th, 2010

This reminds me of what the Democrats did in the deep south in the 1950s to keep Blacks from getting political power.

The issues are old and the precedents are clear. If we had an honest judiciary, none of this would get anywhere. But, of course, much of modern politics would be different then.