Archive for category Uncategorized

The Temper of Our Time – IV

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on September 7th, 2016

In his short book of essays, The Temper of Our Time, the longshoreman-philosopher Eric Hoffer deals with immigration, but not as an economic phenomenon so much as a cultural one. He sees the mass immigration to the US as part of a general upheaval and transitional phase of mankind. Hoffer compares this to personal adolescence, the acquisition of a new identity as one adapts to new situations:

In his short book of essays, The Temper of Our Time, the longshoreman-philosopher Eric Hoffer deals with immigration, but not as an economic phenomenon so much as a cultural one. He sees the mass immigration to the US as part of a general upheaval and transitional phase of mankind. Hoffer compares this to personal adolescence, the acquisition of a new identity as one adapts to new situations:

It is fascinating to see how in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century the wholesale transformation of peasants into industrial workers gave rise not only to nationalist and revolutionary movements giving the promise of a new life, but also to mass rushes to the new world, particularly the United States, where the European peasant was literally processed into a new man – made to learn a new language, adopt a new mode of dress, a new diet, and often a new name. One has the impression that immigration to a foreign country was more effective in adjusting the European peasant to a new life than migration to the industrial cities of his native country. Internal migration cannot impart a sense of rebirth and new identity. Even now, the turning of Italian and Spanish peasants into industrial workers is probably realized more smoothly by immigration to Germany and France than by transference to Milan and Barcelona.

When we look at immigration primarily as an economic phenomenon, we tend to look at the effect on our society and culture first. Hoffer here is as concerned with the effect of migration on the individual doing the migrating, as he is with whether or not there’s a job waiting for him.

I think he unwittingly makes the case for some limitations, possibly some severe ones, especially as regards immigration from Mexico, as much for the good of the Mexicans who come here, as for protectionist purposes.

Mass homogeneous immigration has allowed the immigrants to, in some ways, bring their society with them. If it were just a matter of taco trucks, nobody would much care; who doesn’t like more diverse cuisine? But it’s also a matter of trying to forego what Hoffer sees as an obligatory shock treatment.

For Hoffer, the sense of (sometimes forcibly) shedding an old identity in favor of a new one is dislocating, but it’s a necessary psychological part of the process. That he fits better with his new society is a by-product of his being freed from his old habits and modes of thought and action.

Walter Russell Mead’s fine book, Special Providence, discusses what Mead sees as four broadly-defined schools of American foreign policy. One of them, the Jacksonian, is the most nationalist, but also one of the most distinctively American – we don’t want to fight, but if we need to, let’s beat the crap out of them so we can get home. (Those poor whites of Hillbilly Elegy fame tend to be Jacksonian).

Mead points out that past immigrant groups, mostly but not exclusively European, have often confounded and disappointed the urban and coastal elites by moving to the suburbs and becoming among the fiercest Jacksonians in the US.

I don’t see any reason why the current wave of Latino immigrants shouldn’t be able to follow a similar pattern. But Hoffer makes the case that as long as the numbers are large and assimilation (as opposed to acculturation) is discouraged, it won’t.

The Temper of Our Time – III

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 31st, 2016

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer characterizes that temper as, “impatient.” Perhaps nowhere in the book are the consequences of that impatience more sadly felt than in “The Negro Revolution,” Hoffer’s essay on the race relations of fifty years ago. Looking back at his analysis, we can identify a number of ways in which conventional leftism has contributed to perpetuating an exacerbating the problem over the last half-century.

Hoffer identifies the essential tragedy of the black American:

This country has always seemed good to me chiefly because, most of the time, I can be a human being first and only secondly something else – a workingman, an American, etc. It is not so with the Negro. His chief plight is that in America, he cannot be first of all a human being. This is particularly galling to the Negro intellectual and to Negroes who have gotten ahead: no matter what and how much they have, they seem to lack the one thing they want most. There is no frustration greater than this.

Much has changed in the last 50 years in race relations, some for the good, some for the worse. But when you hear someone say, “Nothing’s changed,” I suspect that it is this, more than anything else, that he means. I think this is still largely true. Black Americans are stuck with a collective identity, whether they want it or not. Leftism has decided that p identity is indelible for all of us, that this a good thing, and that it should be reinforced by government regulation and bureaucracy from the time we are children. In doing so, it’s risked fracturing the country by undermining its basis, but it’s also made things much, much worse for blacks.

How?

The Negroes who emigrate from the South cannot repeat the experience of the millions of European immigrants who came to this country. The European immigrants not only had an almost virgin continent at their disposal and unlimited opportunities for individual advancement, but were automatically processed on their arrival into new men: they had to learn a new language and adopt a new mode of dress, a new diet, and often a new name. The Negro immigrants find only meager opportunities for self-advancement and do not undergo the “exodus experience,” which would strip them of traditions and habits and give them the feeling of being born anew. Above all, the fact that in America, and perhaps in any white environment, the Negro remains a Negro first, no matter what he becomes or achieves, puts the attainment of a new individual identity beyond his reach.

By depriving the black man of the opportunity to create his own new identity, because he’s never been forced to shed the old one. And for some decades now, the rest of us are being encouraged to undo the salutary effects of immigration. (What this says about new immigrants to the US should be pretty obvious. But even then, it’s worth noting that black immigrant from Africa and the Caribbean do about as well as immigrants from other countries, because they’ve had to undergo the immigrant experience.)

In this regard, blacks were doubly victimized by trendy leftism. Black civil rights successes came round about the same time as African countries were winning independence from Europe. Hoffer points out that just as Jewish success in Israel had bolstered the self-confidence of Jews worldwide, blacks in the US should have been a model for Africans. Instead, US blacks were misguidedly encouraged to look to dictators and ideologues like Nkruma for inspiration, setting back their own development at a critical moment of development. Black leaders in the US spent the better part of two decades trying to transplant African nationalist movements into very unhospitable soil.. Thanks for nothing.

Hoffer’s suggestion is one that remains as true today as it was half a century ago:

What can the American Negro do to heal his soul and clothe himself with a desirable identity? It has to be a do-it-yourself job….Non-Negro America can offer only money and goodwill….

The only road left for the Negro is community building. Whether he wills it or not, the Negro in America belongs to a distinct group, yet he is without the values and satisfactions which people usually obtain by joining a group. When we become members of a group, we acquire a desirable identity, and derive a sense of worth and usefulness by sharing in the efforts and achievements of the group. Clearly, it is the Negro’s chief task to convert this formless and purposeless group to which he is irrevocably bound into a genuine community capable of effort and achievement and which can inspire its members with pride and hope.

Whereas the American mental climate is not favorable for the emergence of mass movements, it is ideal for the building of viable communities; and the capacity for community building is widely diffused.

Hoffer makes it clear he’s not talking about the ghetto, but about broader black community institutions, and the re-engagement of the black middle class with the masses. And it doesn’t mean a separate, segregated, parallel society, but black institutions capable of creating a sense of community for people participating in the larger American society. All that talk about deriving a sense of worth isn’t statism or “collectivism” in a destructive sense (although it obvious has the potential for misuse). This is a real part of how people operate in the real world that libertarians ignore or ridicule at their own peril – communities matter to people, even if our legal rights come to use solely by virtue of our individuality.

And here’s the second great betrayal off blacks by the Left. Just as blacks were gaining the chance to remake their own communities with far fewer legal obstructions, the federal government swooped into destroy those institutions by replacing the black father with a welfare check. We’ve seen the results – absent fathers lead to unmanageable boys and now, generations of crime, a downward spiral that make community-building that much harder.

So along with the virtual elimination of legal barriers, the social barriers seem only to have gotten higher. That much, at least, has changed.

The Temper of Our Time – II

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 30th, 2016

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

In his 1967 book, The Temper of Our Time, Eric Hoffer took on the question of race relations, as they’d be called today, or “The Negro Revolution” as he called it then. There are at least two new ideas and several interesting sentences in the essay, but I’ll take as my text his description of how the white unionized longshoreman outside the South saw matters:

The simple fact is that the people I have lived and worked with all my life, who make up about 60 percent of the population outside the South, have not the least feeling of guilt toward the Negro. The majority of us started to work for a living in our teens, and we have been poor all our lives. Most of us had only a rudimentary education. Our white skin brought us no privileges and no favors. For more that twenty years I worked in the fields of California with Negroes, and now and then for Negro contractors. On the San Francisco waterfront, while I spent the next twenty years, there are as many black longshoremen as white. My kind of people does not feel that the world owes us anything, or that we owe anybody – white, black, or yellow – a damn thing. We believe that the Negro should have every right we have: the right to vote, the right to join any union open to us, the right to live, work, study, and play anywhere he pleases. But he can have no special claims on us, and no valid grievances against us. He has certainly not done our work for us. Our hands are more gnarled and workbroken than his, and our faces more lined and worn. A hundred Baldwins could not convince me that the Negro longshoremen who come every morning to our hiring hall shouting, joshing, eating, and drinking are haunted by bad dreams and memories of miserable childhoods, that they feel deprived, disabled, degraded, oppressed, and humiliated. The drawn faces in the hall, the brooding backs, and the sullen, hunched figures are not those of Negroes.

The South has a special burden to bear (although to what extent it still does is another question), but for most of white America outside the South, I think this fairly sums up the attitude, if not universally the work experience. And I think it’s about right. People should be able to pursue their life’s path without laboring under legal handicaps because of their race. I have no doubt that it accurately reflects Hoffer’s own inclinations, and that of his brother dockworkers in mid-1960s San Francisco. They worked hard, and didn’t create or perpetuate the hardships that blacks had suffered.

But if Hoffer understands that the black man’s tragedy is that he can’t be an individual without being seen as black first, he seems to miss who’s doing the seeing. Hoffer’s a union guy through and through, but the union movement in the North gained great strength in response to the influx of black workers during the Great Migration, especially during the Depression, and worked hard to deny blacks the benefits of union membership. Hoffer doesn’t have to answer for that behavior, but he should have at least acknowledged that it existed, and the effects it had on blacks outside the South.

The more relevant question is what it does for blacks. Hoffer’s main point, which I’ll examine in greater length in another post, was the what blacks needed wasn’t cheap, easy, flashy political victories, but community institutions that would give him pride, security, and and self-respect.

The Temper of Our Time

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 28th, 2016

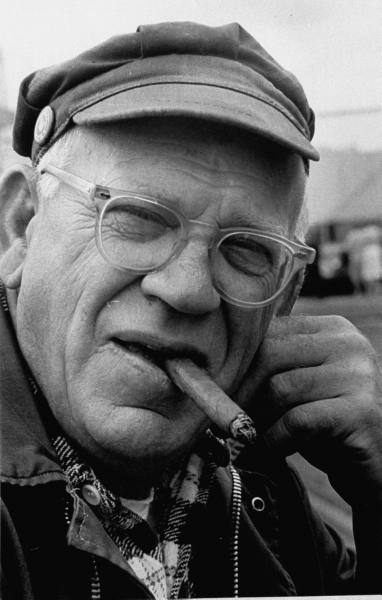

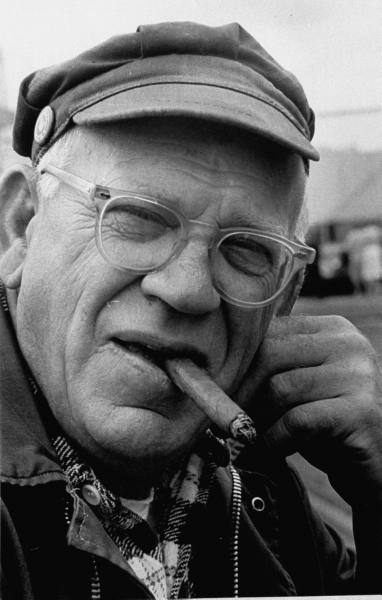

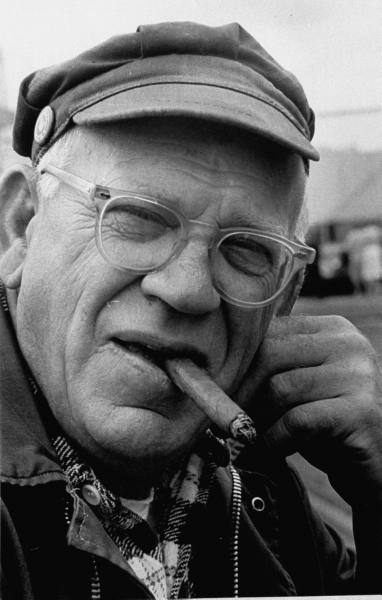

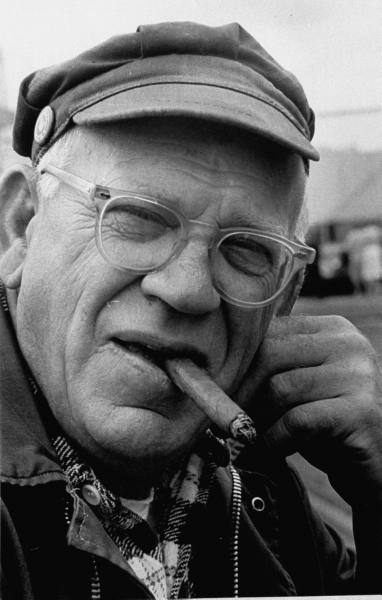

Eric Hoffer was known as the “Longshoreman Philosopher,” mostly because that’s what he was. Born in the Bronx in 1902, he lived most of his life as a migrant worker and then a longshoreman. He had spent 50 years reading, observing, and thinking before producing his first and best-known book, The True Believer, about the psychology of mass movements.

Eric Hoffer was known as the “Longshoreman Philosopher,” mostly because that’s what he was. Born in the Bronx in 1902, he lived most of his life as a migrant worker and then a longshoreman. He had spent 50 years reading, observing, and thinking before producing his first and best-known book, The True Believer, about the psychology of mass movements.

Hoffer’s writing is blunt, direct, thoroughly working-class and thoroughly American, but neither his style nor his ideas are simple. Unlike academicians who do field work in red states, he’s not writing to explain the working man to the rest of the country; he’s writing as a working man talking to the rest of the country.

By 1967, he had written several more books including The Temper of Our Time, which he characterized as impatient, and he provides a number of examples. The book is short – six essays, about 110 pages in all. When his publisher complained about the length, he replied that it had six original ideas and twelve excellent sentences. If he had bought a book of any length that had six original ideas and twelve excellent sentences, he would have felt that he had gotten a good deal.

I think Hoffer sold himself short. I found many more than six original ideas, and many more than twelve superb sentences. I don’t propose to go over all of them here, but let’s start with a story:

When we speak of the American as a skilled person, we have in mind not only technical but also his political and social skills. Once, during the Great Depression, a construction company that had to build a road in the San Bernadino Mountains sent down two trucks to the Los Angeles skid row, and anyone who could climb onto the trucks was hired. When the trucks were full, the drivers put in the tailgates and drove off. They dumped us on the side of a hill in the San Bernadino Mountains, where we found bundles of supplies and equipment. The company had only one man on the spot. We began to sort ourselves out: there were so many carpenters, electricians, mechanics, cooks, men who could handle bulldozers and jackhammers, and even foremen. We put up the tents and the cook shack, fixed latrines and a shower bath, cooked supper and next morning went out to build the road. If we had to write a constitution we probably would have had someone who knew all the whereases and wherefores. We were a shovelful of slime scooped off the pavement of skid row, yet we could have built America on the side of a hill in the San Bernadino Mountains.

And so the paradox of America in Hoffer’s day was – how is it that a country that produces so little leadership in normal times manages to produce great leaders when it needs them?

Hoffer doesn’t directly answer the question, but I think the answer lies in the very capacity for self-organization. People who are capable of self-organization don’t need external leadership to tell them what to do in normal times. What defines abnormal times is the nature of the large-scale projects to be accomplished – winning a war, for instance. But the American’s capacity for self-organization makes the leader’s job easier in those circumstances. Leadership is free to focus on the general direction things need to take, and leave the lower-level problem-solving to the lower levels.

Hoffer’s quote comes in the context of the American genius for community-building. One of the most destructive aspects of leftism has been the shrinking of our citizens’ initiative when it comes to communities, where more and more basic functions are left to city government, and individual or neighborhood initiative often needs to wait for government approval. Even the petty bureaucrats of HOAs enjoy pseudo-governmental authority.

Americans’ ability to spontaneously and collectively solve problems on their own does survive, though, both in the military and in private business. Every successful business I’ve worked in encourages small groups to solve technical problems, and every unsuccessful one has been a top-down affair. When I got my MBA 11 years ago, the management classes were definitely the most trendy social-sciency courses, but they all stressed leadership in terms of empowering employees rather than directing them. That strikes me as a very American approach, where workers generally think of themselves as equal to their bosses.

Presidential Candidates’ Health Then And Now

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on August 22nd, 2016

Hillary Clinton is not a young woman. If elected President, Mrs. Clinton would be a few months younger than Ronald Reagan was when he was first elected. Mrs. Clinton also suffered a fall and a concussion in 2012. The cause of the fall has not been determined, and the extent of the concussion has been the subject of some informed speculation.

Hillary Clinton is not a young woman. If elected President, Mrs. Clinton would be a few months younger than Ronald Reagan was when he was first elected. Mrs. Clinton also suffered a fall and a concussion in 2012. The cause of the fall has not been determined, and the extent of the concussion has been the subject of some informed speculation.

Much of this was covered by the press in 2014, but there have been no definitive answers from the Clinton camp, and as usual, the press has responded with its usual lack of curiosity where Democrats are concerned, and has been content with being stiffed by the campaign.

It has therefore fallen to the Trump campaign to raise the issue, in its usual ham-handed way. The press has responded by, more or less, suggesting that there is something inappropriate in raising the question of a candidate’s health.

And yet, I can recall plenty of speculation about Reagan’s mental capacity in 1980. Mark Russell even did a song about Reagan promising to quit if he became senile while in office.

Another candidate who faced a lot of discussion about his health was John McCain in 2008. A few minutes of googling produced the following:

- On the Campaign Trail, Few Mentions of McCain’s Bout With Melanoma – New York Times

- McCain’s Age and Past Health Problems Could Be An Issue in the Presidential Race – U.S. News

- How Healthy is John McCain? – Time

- McCain’s Health Records – New York Times

- John McCain’s Health – CNN

- McCain Healthy But Cholesterol Concerns Remain – ABC News

- What’s In John McCain’s Medical Records? – Salon

- Liberal PACs Ready Attack Ad on McCain’s Health – New York Times

- McCain Faces Questions on Age, Health – CNN

Indeed, the NY Times post about the attack ad evidences an acknowledgement that some people might be mildly uncomfortable with such an ad, but mostly simply reports on the ads content, and concerns about illegal coordination with the Obama campaign or the Democratic Party.

Uninformed or wild speculation about Clinton’s health is, of course, irresponsible. But merely raising the question?

This seems to be another example of a special “Hillary Rule.”

Love in a Time of Politics

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on February 17th, 2016

Don’t fall in love with a candidate.

It’s ok to love his ideas, or how he presents them. It’s even ok to fall in love with policies, although those are – fortunately – rarely as pure as the ideas.

It’s even ok to decide, after a long, successful term of governance, that one has become attached, and to love an officer-holder for what they have done.

But don’t fall in love with candidates. That’s when they’re ambitious, egotistical, manipulative. They want to win an election, to hold an office. They may believe what they say, and you may like how they say it, but never forget that a candidate is, above all, trying to get something from you. Your vote. For office. For them.

If you love them, they probably don’t even know who you are.

Candidates are, like the rest of us, flawed human beings, with sins in their pasts and compromises to be made in their futures. They will have to trade away X to get Y and it may well be that X is the single most important thing to you in the platform. Nothing personal, just business.

That’s why, when you judge a candidate you do so based on cold calculation of whether or not supporting them advances the political cause. What will they do once in office? Do you trust their judgment, especially under pressure? Can they win? If they can’t win, does it matter, and what can they achieve in the course of losing?

But above all, not, do I love them?

As it is with candidate, whose business is politics, all the more so with a company or CEO, whose business is business, but who gets involved in politics.

Consider the news from Apple today that it will oppose an FBI request to develop a version of its iOS to allow the government to bypass security on confiscated phones.

Some libertarians are cheering Apple as a friend of liberty, a champion of freedom.

I strongly suspect that, to some extent their willingness to fall in love with Apple over this issue is strongly related to their having fallen in love with Steve Jobs’s products, but I can’t readily prove that. Nevertheless, fallen in love they have, at least for the moment.

Tim Cook is no Champion of Liberty. He’s a lefty with a libertarian streak when it comes to his company’s products. He supports gay marriage, which libertarians like, but opposes individual, private freedom of conscience not to participate in those ceremonies, which ought to give libertarians the willies.

He has committed Apple to get 100% of its power from highly expensive, heavily publicly-subsidized “renewable” energy, and refused to disclose to shareholders how much this will cost them.

Cook may or may not be on the right side of the privacy issue. (I tend to think he’s correct in general, but wildly wrong in thinking that two dead mass murderers have privacy rights worth respecting.) But on the whole, Cook is a typical New Oligarch, fond of using the government to tell other people how to live, while chafing at those restrictions himself.

In short, no friend of liberty.

Don’t fall in love with a company.

Neither Obamacare Nor IslamoBomb

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on June 12th, 2015

Opponents  of granting Obama Trade Promotion Authority for the Trans-Pacific Partnership have made comparisons to two other situations, Obamacare and the Iranian Nuclear Talks. Per Obamacare, they argue, the agreement would be approved at the last minute, with minimal understanding of what is in it, and with minimal debate. Per the Iranian Nuclear Talks, opponents want to know, if we trust the administration to conduct these talks, and only require a majority vote, then why don’t we trust them to treat with Iran?

of granting Obama Trade Promotion Authority for the Trans-Pacific Partnership have made comparisons to two other situations, Obamacare and the Iranian Nuclear Talks. Per Obamacare, they argue, the agreement would be approved at the last minute, with minimal understanding of what is in it, and with minimal debate. Per the Iranian Nuclear Talks, opponents want to know, if we trust the administration to conduct these talks, and only require a majority vote, then why don’t we trust them to treat with Iran?

Each, I think, is based on a misunderstanding both of the powers under debate, and the consequences of the agreements being reached, as well as the route we took to get here.

The comparison with Obamacare is more easily dismissed. Unfortunately, Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, whom I like a great deal, fueled this argument with language that was similar to, or could be portrayed as similar to, Nancy Pelosi’s famous declaration about Obamacare that, “We have to pass it to find out what’s in it.” In fact, the TPA’s design militates against a repeat of that debacle.

Here’s the process, as described by Scott Lincicome in The Federalist:

Finally, unlike the oft-analogized Obamacare legislation, the actual text of any final TPP deal will be required by law to be publicly available (online) for months—yes,months—before Congress votes on it. As you can see from the table below (source), under TPA the president must make the entire text of any trade agreement, including TPP, available to the public for 60 days before he can even sign it.Once it’s signed, Congress will have weeks, maybe months, to scour the deal, hold “mock markups” in various committees, and suggest changes to the agreement before the president sends Congress legislation implementing the FTA for a final vote. Also, within 105 days of the FTA’s signing, the U.S. International Trade Commission must issue a report on the deal’s economic impact—again prior those bills being submitted to Congress. And once the bills finally are submitted, Congress will then have up to 90 legislative days (which is like five months in normal human days) to review the bills and hold final votes.

One point that he doesn’t mention is that the TPA’s insistence on an up-or-down vote actually works strongly against the Obamacare comparison. There’s no question that the take-it-or-leave-it approach on the final vote puts some pressure on to approve. But it also prevents the kind of last-minute horse-trading that left Obamacare a mess of barely-comprehended internal contraditctions. Since amendments wouldn’t be allowed, there’s no opportunity for changes in one party of the proposed law to have unexpected consequences, or be in outright conflict with, other parts.

The comparison with the Iran Nuclear Talks is less-easily disposed of. It, too, is going to be subject to a majority vote, after having been negotiated in secret. But the differences are vast. The Iran Talks are essentially about the conditions under which we will remove the economic sanctions on Iran. In the first place, the Administration realized it held the high cards with Congress as soon as it understood that sanctions, as currently constituted, could simply be serially waived by lying about Iran’s compliance and intentions. Any changes to that law would require a majority vote, but then would actually require a 2/3 vote to override a veto.

Moreover, the consequences of getting the Iran deal wrong would be swift, irreversible, and catastrophic. Those of us who don’t trust the administration on Iran – which means most of the country – don’t trust them because there’s basically no way of stopping them from doing that damage, and Obama has shown every evidence of bad faith in pursuit of a deal. While the text of the TPP-in-process is secret, the administration has made virtually no effort to keep the proceedings secret, leaking capitulation after capitulation in the weird belief that doing so will somehow soften opposition. The Iran deal-in-process is known to be a bad one, and in any event, much of what the administration wants to do could be done without Congressional approval prior to Corker-Menendez.

The jury on TPP is still out, and the process doesn’t require any “trust” of the administration or the final product. Nor does it put the Congress in a position of voting on a piece of legislation that still has red-pen markup on it. Depending on the provisions, one could certainly oppose TPP when it comes out without being protectionist. But opposing the TPA on the basis of either of these analogies doesn’t hold water.

Obamacare in the ICU

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on June 10th, 2015

The Hill reported this morning that Congressional Republicans are near a deal on a bill to keep some Obamacare subsidies in place should the Supreme Court rule against the administration King v. Burwell. While this will no doubt be condemned by the usual suspects as proving the party’s insincerity in wanting to repeal the unpopular health care law, it makes sense for both policy and political reasons.

Hill reported this morning that Congressional Republicans are near a deal on a bill to keep some Obamacare subsidies in place should the Supreme Court rule against the administration King v. Burwell. While this will no doubt be condemned by the usual suspects as proving the party’s insincerity in wanting to repeal the unpopular health care law, it makes sense for both policy and political reasons.

Polls show that while Obamacare itself is increasingly unpopular, and has been unpopular for the whole of its existence, they also show that people don’t particularly want an adverse decision in King v. Burwell. But such a decision in Burwell would almost certainly spell the end of Obamacare, as the states with federal exchanges would lose their subsidies, collapsing the rickety system that Obamacare put in place.

How to resolve these apparently conflicting sentiments?

I think the answer is that people dislike uncertainty, chaos, and drama as much as they dislike Obamacare itself. And while losing the subsidies would certainly collapse Obamacare, how it would collapse and how it would effect people on the way down is far from clear. This isn’t a situation where the whole health care system simply reverts to the status quo ante, people’s rates come back down, and the exchanges go away.

Instead, some states would continue to get subsidies, others wouldn’t, and the executive would scramble around in vain trying to prop up the structure. Nobody would know what the rules are, or what they would be tomorrow. This would be true not only for consumers, but for doctors, hospitals, and insurers as well. In short, for at least a while, the health insurance market would simply cease to function in any rational way. The human cost of that chaos would be swift and severe.

What the Republicans are proposing to do is extend the subsidies temporarily until the system can be transitioned away from Obamacare. This will prevent the immediate chaos, and will also possibly having the effect of reassuring that Court that it’s safe to rule against the administration.

Obama will fight this tooth and nail, simultaneously creating the drama while blaming the Republicans for it, in a repeat of the shutdown exercise from October 2013. In this they will, as always, have the slavish cooperation of the press. But the alternative – letting the administration assume the role of hero, even as people find themselves unable to obtain insurance or case – is far worse, and, as mentioned above, may be too much for the Court to swallow.

Even if the “temporary” period extends into the next administration, it would give a Republican president time to work with the Congress to pull together his own plan.

All this is only true, of course, if the actual intent is to repeal O-care and start moving toward more market-based solutions. If it really is just an excuse to put off decisions and lose the momentum of the mid-term elections, then the condemnation will be deserved.

Lincoln Chaffee’s Big Idea

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on June 4th, 2015

Lincoln Chaffee wants us to adopt the Metric System.

Lincoln Chaffee wants us to adopt the Metric System.

Because it’s European, I guess. And because it’s already been officially “adopted” since the late 1800s.

When I was in elementary school, we learned the Metric System, because we had to, and because we were all solemnly and sincerely told that English units were on their way out. And we promptly forgot about it.

In college, where I majored in physics, we did all our calculations in metric, because of exponents. But that’s what it was – the system you did calculations in. In real life, I don’t think I ever measured anything other than Imperial units.

I vividly remember a conversation with a co-worker where we discussed why we hadn’t gone Metric yet.

Cory: Because nobody knows how far a kilometer is.

Me: Sure, I do.

Cory: OK, how far is a kilometer?

Me: Six-tenths of a mile.

There’s a famous post out there about Fahrenheit vs. Centigrade vs. Kelvin, showing that 0F is pretty cold, and 100F is pretty hot, but people can survive in both. 0C is pretty cold, but 100C is dead, and 0K and 100K are both dead, so Fahrenheit is more useful for temperatures we’re likely to encounter. The same is true with all the other Imperial units.

Then, there’s the layout of our cities. Here in Denver, north-south blocks are 8 to a mile, east-west blocks are 16 to a mile, and most other western cities are laid out on some variation of that. You can approximate that with 5 and 10 to a kilometer for a little while, I guess, but it doesn’t take long before the approximation breaks down, and anyway, why do I want to bother with re-adjusting my sense of scale to make Lincoln Chaffee happy? There needs to be a bigger payoff than that for that kind of work.

The Malbim on Esther

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on March 3rd, 2015

Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yehiel Michel Weiser, known to us by the acronym “Malbim,” from his initials, wrote a much-beloved commentary on the Book of Esther. As with most rabbinic commentaries on the Bible, it goes line-by-line, so it falls to the reader to pull together the themes. Fortunately, there’s a more accessible translation, Turnabout, by Mendel Weinbach, which weaves the Malbim’s commentary together into a coherent narrative, faithful to the original.

It opens like this:

The king looked down from a palace tower and sighed. Achashveirosh was a king with a problem. He had power and wealth, and ruled over the entire known world, all 127 nations in it. But he did not like the limited monarchy which characterized his reign. He hated to hear foolish talk about the king’s responsibility to his subjects. How he longed for the absolute power of a Sancheirev or Nevuchadnetzar, who treated their subjects as slaves and had the freedom of doing whatever they desired with them. And talk of wealth! His finance minister was always cutting down on his personal spending with the argument that the national treasury belonged to the people and that the king was only its guardian. How wonderful it would be to have the powers of a Pharaoh and to know that all of the nation’s riches were his own to use as he wished. But it wasn’t the finance minister alone who annoyed this king. Whatever he did he always had to ask some minister or other for advice or approval. Every time he planned some drastic move he was reminded of the laws of the land. So he dreamed of the day that he would no longer have to worry about ministers and laws, and he could exercise his royal judgment freely.

Then this, later on, as the rationale and fallout from his plan to punish Vashti:

The parliament of ministers must be stripped of its power to issue and approve legislation. Henceforth, the king must rule by ukase. His royal decree will automatically become the law of the land, without the approval of any ministers, and it will be recorded in the permanent statutes of the kingdom.

Of course, the Malbim lived in various parts of the Russian and Turkish empires, from 1809-1879, and Turnabout was published in 1971, making both the timelessness and the relevance of the commentary all the more remarkable, no?