With the 2014 mid-terms mercifully (almost) behind us, it’s time to start thinking about the next cycle – the May 2015 Denver municipal elections. All City Council seats and the Mayor will be up for election. You can already hear them touting Denver’s remarkable recovery from the recovery, and no doubt will be citing the city’s reported 4.2% unemployment rate in their campaigns.

If only it were so.

Over on Watchdog Wire, I’ve been keeping track of the Colorado unemployment rate, if you adjust for the state’s increasing population and decreasing labor rate participation. The situation is even more disconnected in Denver. I’m going to go through this in some detail, because it’s worth doing that once. Future posts will certainly shorthand this.

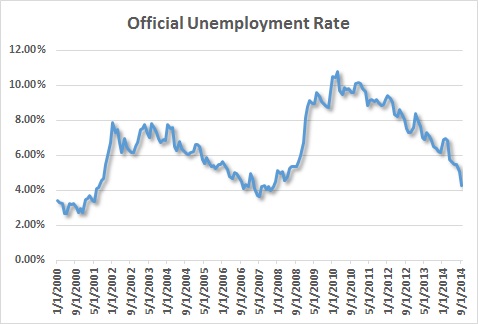

First, here’s the nominal unemployment rate, as reported in most of the media:

Looks pretty good. We’ve been on a nice, downward trajectory since early 2010, and we’re almost back to pre-recesssion levels. Also, take this chance to note the seasonality of Denver’s employment, mostly around the school year and holiday retail.

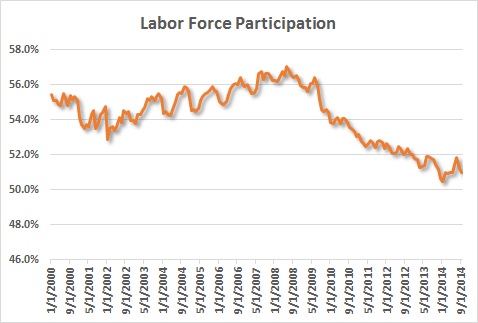

Unfortunately, the number of jobs hasn’t kept pace with the population growth:

Since the previous peak of employment, in 2008, Denver has 15,000 more jobs, but around 90,000 more people. So why is the unemployment rate down? Because a smaller percentage of the population considers itself part of the labor force:

At its peak, in June 2008, 57.1% of the population considered itself part of the labor force – meaning that those people were either working or looking for work. Since then, the percentage has declined, even as Denver’s population has increased substantially. What would the labor force look like if participation had kept pace with population growth?

That’s about 40,000 people who would be int he labor force who aren’t. If we counted those people as being in the labor force, what would the unemployment rate look like? Honestly, it looks like depression-level unemployment:

That’s right, just under 14.5% unemployment for the City and County of Denver, if people hadn’t exited the labor force in such numbers over the last few years. In order for the real unemployment rate to match the stated unemployment rate of 4.2%, Denver would need to have created about 38,000 more jobs than it has.

When this calculation is made nationally, one counter-argument has been that as the Baby Boomers get older, Americans are basically aging out of the work force, with a higher percentage of the population 65 or older. Those people naturally shouldn’t be counted in the labor force. But that argument doesn’t hold for Denver. In fact, the opposite is true. Here in Denver, according to Census estimates, the percentage of the population that’s 18-64 has increased since the recession, as the city enacts pro-density zoning and planning policies:

It’s not much of a difference: 65% to 68.5%, but it certainly doesn’t sustain a story of large families and urban retirees.

Either many people working aren’t being counted in the employment figures, or else the employment situation – and thus the state of Denver’s economy, is far more fragile than we’re being told. Either way, this has serious policy implications for the route that Denver’s government is taking. The increase in population is not an accident – it’s the result of a deliberate policy of densification. And if the increase in property values and “recovery” in jobs is for an increasingly narrow portion of the city, it also means that fewer and fewer people will be paying the higher and higher taxes needed to pay for politicians’ desiderata, making Denver less and less friendly for the middle class.