|

|

Main

May 22, 2009

Now It's Municipal Bonds

The financial wizards who brought us the mortgage debacle now want to do the same for municipal bonds: One piece of legislation would provide the Federal Reserve with the

authority to fund new liquidity facilities for some municipal

securities. Another would provide federal re-insurance for municipal

bonds, which seeks to make it easier to for municipalities to issue

municipal debt to raise money.

...

House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank, D-Mass.,

defended legislation to create a federal re-insurer, arguing that the

marketplace imposes unfairly high interest rates on municipal bonds,

which typically have a lower rate of default than corporate bonds

"We need to have the safety of municipal bonds reflected in the

interest payments on those bonds," Frank said. "The market plays a very

important role but market failure is also a factor."

Well, he'd know about market failures, having helped create the last one. What he wouldn't know, wouldn't have any idea about, is what the proper interest rate premiums are for municipal debt. If Mr. Frank thinks that municipal debt is a bargain, he's always free to buy some. Why doesn't he just suggest securitizing such debt and chartering companies to buy the securities?

There are already companies that insure municipal debt, so there are two, mutually-reinforcing markets already at work here. If he really thinks that these companies are under-capitalized, there are plenty of regulatory remedies already available. In fact, there's excellent reason to think that what's really going on here is an attempt to bail out California without having to tell people that's what you're doing. Because they might not like that.

April 19, 2009

The Least Important Leading Indicator

1) Consumer sentiment is useless is predicting

the single most important engine of economic growth 2) Since it's

somewhat correlated with media coverage of the economy, attempts to

jawbone up the economy are doomed to fail, or at least be irrelevant. 3) Consumer sentiment during non-recessionary periods of Republican and Democrat administrations over the last 28 years clearly shows patterns that indicate more favorable coverage during the Clinton years.

This:

U.S. consumer confidence rebounded this month to the highest levels since the demise of Wall Street, according to a highly regarded study.

The University of Michigan's Consumer Sentiment Report, released today, is based on a scale of one to 100, and preliminary April figures show confidence rose to a level of 61.9, up from 57.3 in March. This is the highest index reached since September, when the survey recorded a 70.3.

In the study, people said they're feeling better about spending money because they think the recession is going to bottom out this year, not because their personal economic situation has improved.

And why would they think that? Well, why do you think?

Most consumers really only know about their own situation at the moment. They're going to form their opinions about the broader economy based on 1) what they're hearing in the press and 2) what they're hearing from their friends, co-workers, and businesses. And as much as we don't like to admit it, voices of authority such as the President and the Fed Chairman still carry weight, especially when reduced to optimistic sound bites. Worse, this statistic has just about no predictive value. I correlated the St. Louis Fed's record of Consumer Sentiment with the change in personal spending, month-over-month, for the last 30 years. I lagged them from 0-12 months. The best correlation was lagged by one month, meaning that consumer sentiment best predicted next month's increase in spending. It correlated at 0.22, which is pretty meaningless, and has an r-squared of 5%, meaning that the best, the best that this does is to predict 5% of next month's increase in personal spending. OK, I hear you say, but both numbers are sort of bounded. After a while, you can be making more than you're spending, top out your spending, still be feeling really good about the economy, but not feeling better, and not spending more. Aha! The month-to-month change in sentiment predicts less than 1% of the change in personal spending for any month in the coming year. This means that 1) consumer sentiment is useless is predicting the single most important engine of economic growth, and 2) since it's somewhat correlated with media coverage of the economy, attempts to jawbone up the economy are doomed to fail, or at least be irrelevant. But when you look at the graph of consumer sentiment, and compare it with GDP growth, something else emerges:

Sentiment recovers during the first years of the Reagan Administration and then stays high, but flat until the recession of 1990-91. It then recovers as the economy begins to, only to dip again just in time for the election. At which time it goes on an 8-year, unbroken upward trend, cresting and then declining with the election of George W. Bush. The attacks of 9/11 no doubt helped push it down, but in fact, we were headed into a recession at that point, anyway. Then, despite the recovering a prosperous economy until 2007, sentiment bounces around, but trends flat for the decade. There's never any one, single cause for anything outside of physics, but there's pretty strong evidence here that unremittingly positive coverage during the 90s pushed up sentiment, while unremittingly skeptical coverage during the Bush years helped keep it in check. The good news is that this probably didn't actually affect the real economy. The bad news is that it almost certainly affected out politics.

April 2, 2009

Like They Can Just Print the Money

I'm beginning to think that having put the State Capitol near the Mint was a mistake. I think the Democrats are beginning to think that they can just print their way out of whatever burdens they put on the state.

We found out last month that the Colorado Unemployment Insurance Fund was safe, despite climbing unemployment numbers:

Reforms instituted a generation ago appear poised to keep the system solvent even as other states see their unemployment programs go broke. And work is under way to improve the department's Web site this spring, which should make it more user-friendly and ease the strain on the phone system.

...

In the 1980s, state lawmakers set out to protect the state's Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund -- it is used to pay benefits to people who lose their jobs -- after watching it go broke in a recession.

The result was an additional tax, dubbed a "solvency surcharge," that was designed to kick in whenever the trust fund's balance fell below 0.9 percent of the wages paid in the state. The calculation is made each year on June 30, and in 2004, after three years of recession, the tax kicked in.

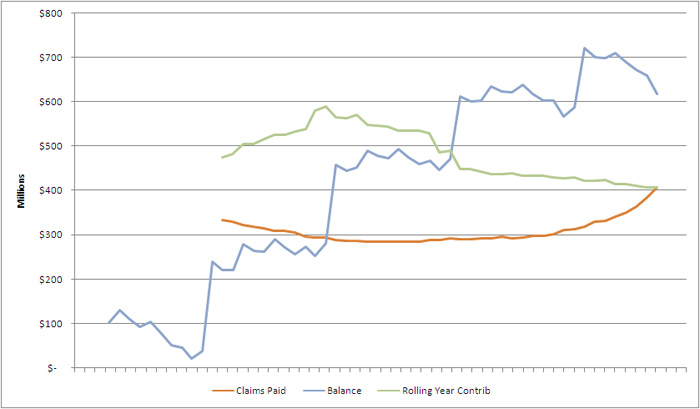

The result: Colorado's unemployment trust fund grew to $672 million last fall, just as the latest recession was taking hold. That allayed fears that Colorado could again find its unemployment fund out of money.

...

"It would take a deep recession that went on for several years before we would go insolvent," [Mike Cullen, Colorado's director of unemployment insurance] said.

His assertion is backed up by various scenarios that have been considered, including a moderate or even severe recession, said Alex Hall, the department's chief economist.

"Certainly with all the information we have available at this time, and what we feel are reasonable scenarios, including scenarios that take us into a pretty deep recession, we feel that the surcharge is providing that stability and revenue for the unemployment insurance trust fund, and that solvency will not be an issue for us," Hall said.

Well, not so fast there, cowboy.

In a state budget outlook delivered week, the Colorado Legislative Council Staff predicted the fund balance "will fall precariously close to insolvency" to just $44 million by June 30, 2010, down from nearly $700 million on June 30 last year.

The Colorado Department of Labor and Employment expects a healthier fund at $187 million on June 30, 2010, but still has concerns, said Mike Rose, chief of statistical programs for the department.

"We also consider it possible that the fund might be marginally solvent at periods in 2010 and 2011," he said Wednesday.

Unemployment insurance payouts are expected to total $834.1 million in the current fiscal year that ends June 30 and stay at that level for another year, according to the council forecast.

In the midst of this, the legislature seems poised to pass HB 1170, which would entitle employees who are locked out - that is, they have jobs but are involved in a labor dispute - to receive unemployment benefits.

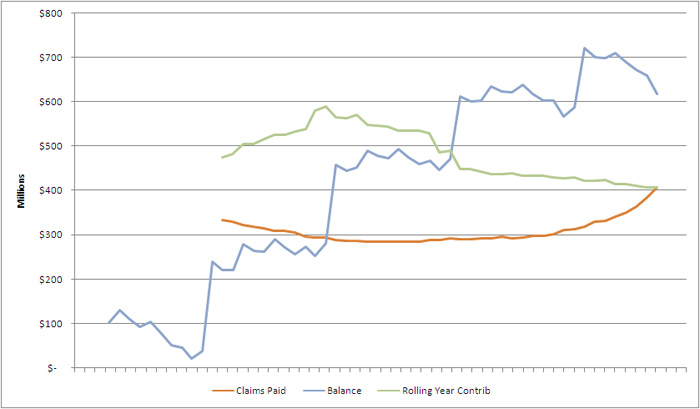

Here's a chart showing the monthly balance of the Colorado Unemployment Insurance Fund, along with a 12-month moving average of employer contributions and benefits paid out:

The reason I've smoothed out these payments and contributions is that employer contributions are extremely seasonal. They generally see a large jump in May, when the surcharge is assessed. They also tend to have almost no contribution during the last month of each quarter, while the first month of each quarter is the highest.

So, the payouts are still rising, and have just passed the contributions. For the first time since the recovery from the last recession, we've seen an actual drop in the fund's balance. Even if all those conveniently-times stories about how we're hitting bottom are correct, unemployment is a trailing indicator. Since contributions are based on the current aggregate salaries paid, that means that contributions will fall even as unemployment rises. This dynamic refills the coffers during the latter part of recoveries and prosperity, but drains them towards the middle and end of recessions.

Then, there's this:

A state Senate committee took up a bill Wednesday that would make Colorado eligible for $127 million in federal stimulus money for the fund by expanding the definition of who can qualify for jobless benefits. It would cost the state an estimated $14.6 million in the fiscal year that begins July 1 to make the changes, largely to pay benefits for newly eligible residents.

So we'll pick up a net $100 million this year, at the cost of no future returns and nobody-bothers-to-ask how much more in perpetual commitments down the line.

The only way out is to float debt. If we end up having to do this during an inflationary period, it'll mean higher rates and even more trouble down the line.

Unemployment insurance is well-established by now. But I can't help wondering if it wouldn't be better to give it to the employees up front rather than paying to the government for what passes for their traditional definition of, "safekeeping"

March 31, 2009

Lawlessness Under Cover of Law - II

Turns out if you work at a company that's taken federal money, the government's going to save you having to wait until your company derives your new pay scale from what they can pay the CIO this month. But now, in a little-noticed move, the House Financial Services

Committee, led by chairman Barney Frank, has approved a measure that

would, in some key ways, go beyond the most draconian features of the

original AIG bill. The new legislation, the "Pay for Performance Act of

2009," would impose government controls on the pay of all employees --

not just top executives -- of companies that have received a capital

investment from the U.S. government. It would, like the tax measure, be

retroactive, changing the terms of compensation agreements already in

place. And it would give Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner

extraordinary power to determine the pay of thousands of employees of

American companies. ...That includes regular pay, bonuses -- everything --

paid to employees of companies in whom the government has a capital

stake, including those that have received funds through the Troubled

Assets Relief Program, or TARP, as well as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The

measure is not limited just to those firms that received the largest

sums of money, or just to the top 25 or 50 executives of those

companies. It applies to all employees of all companies involved, for

as long as the government is invested. And it would not only apply

going forward, but also retroactively to existing contracts and pay

arrangements of institutions that have already received funds. (emphasis added -ed.)

On Backbone Radio a couple of weeks ago, my colleague Matt Dunn and I disagreed on whether or not the government should try to claw back the AIG bonuses. I didn't think so, but could see there was an argument in using AIG as a cautionary tale to keep others from taking the bait in the first place. Matt was wondering why the Republicans weren't making a bigger issue of this. Turns out we were both operating under the delusion that there were still rules. Readings of the Commerce Clause have been increasingly detached from reality for the last 70 years, beginning with a decision that selling corn within the borders of Indiana somehow constituted interstate commerce, because corn is fungible. This was followed by a decision that a company was engaged in interstate commerce because its suppliers' suppliers moved products across state lines. Since the government hasn't provided any exit strategies for these,

ah, "investments," this amounts to a perpetual pay schedule. And you

thought that post-graduate degree was going to open the door to someone

more than a GS-8. In fact, Treasury is considering dispensing with the requirement that you have received Federal money, requiring only that you be publicly traded. Given the open-ended nature of this commitment, it's only a matter of time before the employees of these companies demand that their competitors be held to the same standard. After all, it's only fair.

March 29, 2009

Freddie and Fannie, Together Again

The Wall Street Journal is reporting that the Obama Administration now wants to use Fannie and Freddie as a source of warehouse capital for small mortgage banks. The regulator has asked representatives of mortgage banks, including

the Mortgage Bankers Association, to come up with a detailed plan for

Fannie and Freddie to help mortgage banks get credit. John Courson,

chief executive officer of the association, said in an interview that

the plan should be ready to be presented to the regulator within about

a week. One possibility is that Fannie and Freddie will guarantee debt

issued by warehouse lenders, making it easier for them to provide

financing to mortgage banks. ...

Mortgage

banks typically are small, family-owned companies. Unlike commercial

banks or thrifts, they aren't licensed to take deposits and so don't

have that source of money for their loans. Instead, they borrow money

from warehouse lenders, which often are units of larger banking

companies. The mortgage banks use the short-term credit to provide

loans to their customers and then pay back the warehouse lenders after

selling the loans to bigger banks or to investors such as Fannie or

Freddie. (emphasis added -ed.)

In short, the mortgage banks were one of the prime sources of securitization. Properly done, securitization is a good thing, and if the buyers, rather than the sellers, assess the risks, then there's some chance it could work again. But it's far from clear that the mechanisms are in place for banks to assess these risks. The lack of warehouse capital itself should be a sign that those funders don't believe there are buyers yet for mortgage-backed securities. So, rather than let that market re-develop on a sounder basis, the Obama Administration plans to lend the mortgage banks the money to originate the loans which it then plans to buy itself. The Administration apparently has tired of even trying to conceal the financial shell games it's playing.

March 12, 2009

Bank Sale Rashomon

New Mexico based First States Bank is selling is Colorado banks, known as First Community, to South Dakota-based Great Western Bank, which itself is owned by National Australia Bank. Papers in all three states reported on the sale, but in very different ways. And each tells an important story larger than this sale.

The Las Cruces paper leads with the fact that First States is changing its mind about that TARP money, after all:

Albuquerque-based First State Bancorporation says the sale of its Colorado bank branches will improve its balance sheet enough to eliminate any need to accept federal bailout money.

First State, which does business as First Community Bank, will focus its attention on the New Mexico market, the Albuquerque Journal reported in a copyright story Thursday.

...

Stanford said availability and terms of the federal Troubled Asset Relief Program funding is too uncertain and that First State has withdrawn the application it submitted last October.

The bankers don't like the fact that, increasingly when doing business with the Federal government, a deal really isn't a deal, after all. So rather than get caught in that particular tarp, er, trap, they decided to raise their capitalizatino to 12% from 10% by selling off some of the bad loans.

Both of the Colorado reports, from the DenPo and the Denver Business Journal, mention that it was Bob Beauprez who sold the under-performing banks to First State in the first place. Bad news for an election run this cycle, I'd think.

But neither mentions why Great Western would want to take on this burden. Leave that to the Argus-Leader:

The acquisition involves the purchase of 20 branches and will allow Great Western to expand its small business and agriculture lending, said Jeff Erickson, president and chief executive at Great Western.

"The addition of these Colorado branches is consistent with our strategic growth plans and gives us the opportunity to expand particularly in the areas of small business and agricultural banking," Erickson said.

So it would appear that rather than beg for federal money with Lilliputian-quantity strings attached, a bad sold off an underperforming ball and chain to another bank who saw opportunity there instead.

I can't believe either presidential administration meant for it to work this way, but the raging uncertainly surrounding TARP may be forcing smaller banks to actually let the market operate.

It's Great Time To Raise Taxes

So say a majority of the Metro Mayors Caucus, who want to double the portion of the local RTD sales tax to make sure that the Great White Elephant of a light rail gets built on time and massively over budget.

We can't actually tell which mayors thought that raising taxes in the worst economy since the invention of money was a good idea, and which ones thought they should wait until next year, when all the people who had money to spend were out of work, because neither of the Post's two articles, nor the Caucus's page itself tell you. It's a good thing there are professional journalists around to keep us informed.

They estimate that this glorified Disney monorail is going to suck another $2.2 billion out of the regional economy over the next 8 years. In fact, as has repeatedly been shown, both the cost and revenue forecasts are little better than ouija boards. Denver had no idea well into the 4th quarter of last year how far south its sales tax revenues were headed, and budgeters missed both the commodity price decline of the T-Rex years and the jump in construction prices over the last couple of years.

There's no guarantee that even this amount will be enough, and if mirabile dictu, the thing somehow manages to come in under the excess projected, they'll find some other way to spend the money.

Here's a better idea. Make choices. Like the rest of us.

What Does Lois Court Have Against Small Business?

Lois Court (D - Economic Cluenessness) joined all four Boulder Democrats in the State House yesterday in voting against Declaring March 9 - 13 Small Business Week. (By the way, Randy, Rep. Fischer from up there in Larimer County also dissed the bill. Raise an extra glass to the Maya Cove's owners next week, will ya?)

This is the sort of pro-forma measure that usually sail through by a combined 100-0, and if anyone pauses to comment, it's usually to sing the praises of whatever group is being honored.

Admittedly, there was a dig in there about the estate tax, but people die in Boulder and east Denver just like everywhere else. Stating that an estate tax can be a powerful disincentive is just stating an economic fact. It's like voting against a resolution honoring the astronauts because there's a clause in there stating that solid rocket fuel is dangerous and should be handled with care.

Maybe they didn't like the line about small business having a harder time getting credit, because it reminds people of all the money we're borrowing.

Maybe this is like voting against a Children's Day, because every day is Children's Day, and under the Dems, they want every business to be a small one.

I really have no idea. There are 59 Democrats up on Capitol Hill, and 48 of 'em were able to make their peace with this non-binding sense-of-the-legislature that wealth comes from entrepreneurial brains, rather than legislative luncheons.

February 26, 2009

Creating Another Patronage Class

Or, "Taming the Wild Entrepreneur."

From the WSJ's description of the President's tax plan:

As expected, Mr. Obama proposed raising taxes on private-equity fund managers and venture capitalists, by taxing their profits as ordinary income instead of capital gains. That change would raise $23.9 billion over 10 years, according to White House budget office estimates.

I seem to recall the President making some comment in his speech to Congress about helping entrepreneurs. (Maybe I remember it because it was one of the few times where Nancy "Jumping Bean" Pelosi took a brief break from her calisthenics.) Where does the President think entrepreneurs get their capital? Removing this tax break may raise a few billion in the short term, but it removes a key incentive for capital to flow to entrepreneurs in the first place, which means that, like all tax increases, it will ultimately raise far less than projected.

This is self-defeating. Unless, of course, the President wants the government to pick the inventors who'll get the money instead. Almost certainly, he'll claim that he's supporting entrepreneurship by redirecting money into green energy startups. That, combined with his ongoing attack on the oil and coal industries, designed to make green power more competitive by making oil and coal more expensive, will allow him to claim that government investment in just as efficient and effective as private investment.

Of course, it does expand another patronage class, directing creativity where the government wants it to go, with the added satisfaction of making the inventor beg to the government for support.

As for the private-equity funds, those are the funds that have the most flexibility and creativity. Obviously, we'd want to punish them, as well. Stock appreciation is no less a capital gain when one of those funds sees the benefit, than when yours or my 401(k) or IRA sees it, but the President wants to treat them differently, because most private equity investors are successful and prosperous.

One last note. On Tuesday night, the President said that, "if you earn less than $250,000, your taxes won't go up one dime." Turns out he wasn't talking to individuals, but to married couples. If you live in the northeast, it's pretty common for each spouse to bring home $125,000 apiece, and it doesn't go all that far.

We really have elected a cross between FDR and Wesley Mouch.

January 31, 2009

"Worker Retention" - II

President Obama has paid his first installment to the unions, instituting a "Worker Retention" policy for federal contractors, of the kind Denver is considering at the local level. You can read the text here, via shopfloor.org. Mickey Kaus (HT: Powerline) gets at least one of the problems with it.

I wrote about this disaster of a public policy proposal the other day, but more has occurred to me since them. This, of course, is aside from the bizarre act of giving the employee an overt property right in a contract he had no hand in winning, and in fact, may have in fact helped cost his current employer.

As part of that patronage extension, there's the virtual elimination of any incentive to actually perform the work involved.

If the Denver City Council is so convinced that this policy would save the city money, they must be equally convinced that, had it been in place, it would have saved the city money over the last decade or so. So why don't they go back, dig up all the contract rebids over that period, see which ones changed hands, and see how much of the savings was attributable to labor costs.

Better yet, how about some enterprising reporter who actual job it is to cover these things goes over the last year's worth of contract re-competes and makes that calculation?

January 29, 2009

"Worker Retention"

That's the term for a recession-induced, recession-prolonging piece of extended patronage being considered by the power-conscious but economically illiterate Denver City Council.

According to the Denver Post, the City Council is considering enacting so-called "worker retention" laws for city contracts:

Now Nevitt and eight other members of the 13-member City Council say they want to extend "worker retention" for all service contracts for the city and airport.

Firing workers just because a new contractor comes on the scene is "both inefficient from an operational perspective, expensive from a budget perspective and cruel from a personnel perspective," Nevitt said.

Oh-for-three. There's no particular reason to think it's inefficient operationally: if the duties performed are routine, the new, winning bid may in fact derive from operational efficiencies. It's less expensive by definition, as the winning bid by a new company must be, by definition, lower than the incumbent's bid. As while nobody wants to see anyone else lose his job, where's the kindness in leaving the winner's employees on unemployment?

It's perfect reasonable for people to seek security in this economy. You think I'm not worried about my job, too? But pressure to keep wages high was one of the chief factors in the New Deal's prolonging of the Depression, and this bill would do nothing if not keep wages artificially high.

Finally, this basically extends permanent job security from direct city employees to city contractors, in effect creating an entirely new patronage class dependent on the largess of city budgets.

January 15, 2009

Borrow In Haste, Repay At Leisure

Colorado Republicans have proposed mortgaging government property to pay for transportation projects, up to $500 million.

The Democrats, naturally, want to raise your taxes permanently instead, and would net only half the amount the first year.

Right now, Colorado general revenue bonds, which are basically secured only by the moral obligation of the state to pay its debts, are paying about 1.5% yield to maturity. Paid back over 15 years, that's about $35 million a year in payments, or about $6 a person per year, for $500 million.

The Democrats want to secure a permanent funding stream out of your pockets, at about 4 times that rate, in the middle of what they've consistently called the worst economy since the Great Depression.

The Republicans want to borrow at a ridiculously low interest rate, heading into what will likely be an inflationary environment sometime in the next two years. That inflation will only increase borrowing costs.

The Democrats want to build in more structural spending, and then, when inflation eats away at the value of the taxes they're collecting, complain about shortfalls and raise rates again.

And this is without ditching TABOR.

January 1, 2009

How Not To Invest In Real Estate

Colorado will receive $34 million to buy up distressed properties. Of that, Denver will get about $6 million.

This isn't right, This isn't even wrong.

Look at the path the money follows to get here:

The state of Colorado will allocate the HUD funds, and community development groups, with the help of elected officials, will use the money. NSP money can be combined with HUD's Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program funds as well as other funding resources.

This doesn't even include all the administrative costs; some of the $6 million will go to those, as well. The fingers in the pie include: the IRS, HUD, the state of Colorado, community development groups, local elected officials, who will rely on local bureaucrats, all of whom have incentives to maximize their respective cuts, none of whom have incentives to actually improve neighborhoods. I'd love to see the cost accounting at the federal, state, and local levels for this cash, but none will be forthcoming, I'm sure.

Worse still, $6 million isn't even worth the effort. According to the City Assessor's Office, we can roughly value all the residential real estate, both real property and condos, at about $40 billion. Six million isn't enough to arrest a trend of declining home prices; it is, however, enough to pick favorites and reward allies.

If there are distressed properties for improvement at a profit, there are plenty of investors willing to risk their own money, without having to make the round trip through three different bureaucracies.

Maybe they could even hire some of those paper-pushers to do the framing.

Rationalizing Costs & Revenue

The Governor of Oregon has come under fire for wanting to replace the gas tax with a mileage tax. He wants to use GPS to track residents' mileage, and then assess the tax at the pump.

At first glance, this might seem like the right way to assess the tax. Wear and tear on roads is more closely related to miles driven than to gallons of gas consumed. In practice, it's a terrible mis-assessment of taxes, raising questions of jurisdiction, cost-to-revenue matching, government-sponsored behavior modification, and CAFE standards. And that's without the intrusiveness of the government watching where you drive your car.

If gas tax revenues are down, it results from some combination of better mileage and less driving. Better mileage undermines the argument for higher CAFE standards, as it happened without them.

Less driving - supposedly the behavior we all want - shows the dangers of using the government as a massive behavior-modification program. Governments do a terrible job of matching revenue structure to cost structure; if successful, the programs that were dependent on sinful excess suffer.

I've written about Denver Water's experience (and now neighboring Aurora's experience) a couple of times. Almost all of their costs are fixed, so higher charges result in lower usage, and less revenue, but does little to lower costs. They raise rates even further, enraging consumers who are already watching their yards turn brown in years of plentiful snowpack.

We've seen this with smoking. Smoking in the US is down, and yields on tobacco-backed revenue bonds are up. Long-term bonds paying 5% coupon are routinely priced at 9% yield-to-maturity. This in a declining interest-rate environment, with a tax-free coupon. Often, these bonds are now rated at just over junk level.

Ideally, fees would allocate taxes to the roads being driven and their maintenance costs, from the drivers using them. But it isn't necessary to tax each driver preicsely; it's only necessary to make sure that aggregate collections match aggregate costs.

A mileage tax would tax only Oregonians. But they drive in neighboring states, and Washingtonians and Californians use Oregon's roads. All things being equal, I'm most likely to fill up in a jurisdiction where I do most of my driving. And under such conditions, a point-of-sale system would ensure that every jurisdiction would collect its fair share of road use taxes over time.

All things being equal. Of course, they're not. I no longer drive out of my way to get better gas prices. But I will try to nurse a tank to get to the cheapest gas near my regular route. Bureaucrats argue that this leads to competition. As though there were something wrong with that.

December 12, 2008

Bad Markets Mask Problems, Too

Hank Paulson, and now the British, are complaining that the bailout money available to the banks isn't being lent. So why not? Well, it's not because banks are happy to sit on fat piles of cash while you and I look for work. And it's not, contrary to some conspiratorial emails I've gotten, because the bank want to own everything from the GM to your house. Banks make money by lending. They don't make money by being in the real estate business, or the car business, or any other business other than lending. They want to be able to judge good managers of those businesses, but they neither have nor want the skills to run those businesses themselves. So why aren't they lending? It's because they can't find anyone they want to lend to. They won't lend to other banks because they can't tell which banks are sound and which aren't. But most of their business comes from lending to businesses, and right now, it's almost impossible to tell which businesses have good stories and which don't. I spoke which a friend of mine who invests money for a living. He's a value investor, and a good one, and his complaint was that every company had one of two stories: it wouldn't make it, or it had a great model for when the economy turned around. The valuation measures he uses - that most value investors use - aren't distinguishing between merely good companies and companies actually worth investing in. It means that almost every company's story is now the macro story, the story of the larger economy, not its own. And it means that the market, the individual decisions that individual investors make about individual companies, is being driven by the uncertainty in that macro picture. The sooner we let the market find a bottom, the sooner we let the economy adjust, the sooner those valuation measures will begin to make sense again, and the sooner we can start turning this thing around. Or, Obama can take all that FDR talk seriously, and we can be having the same discussion 7 years from now.

December 11, 2008

More Bailout Follies

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and

diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the

public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is im-possible

indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be

executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though

the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes

assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such

assemblies; much less to render them necessary.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

Even though the bailout package now seems to be debt-based rather than equity-based, the basic dynamic hasn't changed - the government is going into business with the Big Three. It isn't merely requiring such meetings, it's participating in them.

What's even weirder is Elisabeth Moss Kanter's discussion of the lack of green planning by the Big Three, as a condition for receiving public funds: All three of the plans talk about how they're getting

better at building cars to [meet] market demand. Pause for a moment and

think about that. These are the biggest advertisers probably in the

world. And that makes it sound like they're passive recipients of

consumer preferences, as opposed to shaping consumer preferences. So I

would ask [the car companies] what are you going to do in your

advertising and marketing this time to guarantee that the public

actually wants green cars?

Implicit in the patronizing notion that people can be bludgeoned by advertising into wanting something they don't want, is the notion that they should be. By government fiat. Leave aside the fact that the so-called "green" cars will create an increased demand for electricity that regulators are doing everything to not meet.

People aren't buying green cars because the payback periods (including increased and naturally-rising maintenance costs) extend well past the second century of the Cubs' rebuilding program. If you pay more that you have to for the same item - in this case, getting from home to your job - you'll have less left over for everything else, including reitrement. That's called a lower standard of living. You might try to offset this by buying into one of the rent-seeking green companies, and that'll work until everyone buys in and reduces returns to market rates. Inefficient investment is no more better for an economy than inefficient purchasing.

So what Prof. Kanter is proposing is that we use our own money to persuade ourselves to live more poorly. As the Powerline guys put it, lower living standards aren't the solution, they're the problem.

December 10, 2008

Bailout Exit Strategy

Under what conditions would the government liquidate its proposed stake in the car companies? In short, what's the exit strategy. Should the companies become profitable again, there may be considerable pressure for the government to stay in the game and collect dividends. And even if the car companies wanted to buy out the government, it might never be to their financial advantage to do so. If the shares are over-valued, it's to GM's advantage to let them drop before buying. If undervalued, GM's move to buy would be interpreted as such, and the government might well choose to them the shares appreciate. But the real threat here is regulatory. The Big Three would find themselves with a friend in government, more able than ever - and with a profit motive to boot - to muck around with the rules to the benefit of rent-seeking auto companies, and with a proven disinclination to defer to market discipline. Our own Diana DeGette, Congressman for Denver, is Chief Deputy Whip, thus a part of leadership. She's also the outgoing Vice Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, so will exercise considerable oversight of this monstrosity. I just placed a call to her office for clarification (1:15 PM Denver time), and am awaiting a reply.

Rebuilding the House of Cards

With its Treasury assets low, the Fed is considering issuing its own debt, something it's never done before, and may be prohibited by law from doing. The central bank has seen its balance sheet more than double, to over $2 trillion, and is trying to come up with added flexibility. This is a spectacularly bad idea, so I'd expect to see enabling legislation on the President's desk by next week. Anyone who buys Fed debt would be basically buying all those risky assets - plus whatever new risky assets the Fed decides to backstop tomorrow. The market doesn't think much of those securities, which is why the Fed had to step in and buy them in the first place. On the open market, they'd have insanely high yields and minimal value. What the Fed is proposing to do is to remarket those securities, in effect as CDOs without the tranches, rebuilding the house of cards that got us into this problem in the first place. Any difference between the yield those securities would be required to pay on the open market and the interest rate the Fed would have to pay would be - totally and completely - based on the public's confidence in the US Government's ability to cover those costs. In other words, you and me. There are also almost certainly conflicts of interest (so to speak) between the Fed's role as a stabilizer of the debt markets and its role as a participant in them. It's one reason the Fed has been independent, with the ability to tighten money and drive up borrowing costs largely without interference from the Treasury. The Fed as debtor may be much less willing to fight inflation.

December 8, 2008

The Problem With Experts

The problem with experts is that they're awful at predicting the things they're supposed to predict. Nassim Taleb makes this point in both Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan. The problem with reporters is that they don't bother to check how well the experts have done in the past. The CU Boulder's Leeds Business School released its Business Economic Forecast for 2009. Both the Post and the Rocky reported on it, doing little more than repeating the predictions. Now, the whole thing's available for download here. Looking back over the 2005-2007 predictions, they've done all right, but nothing spectacular. And this year's prediction spent time on the housing market, but completely missed the financial crisis and the mortgage industry's spillover into the rest of the economy. The 2008 forecast doesn't even mention the word "mortgage" outside of the housing industry survey. In terms of percentage change in total employment, they were off by 8% in 2005, 1% in 2006, and 17% in 2007. That's not bad, but their sector-by-sector results aren't so good. They've consistently underestimated the Mining sector's growth, as well as government growth. They're almost never under 10% relative error on these estimates. When the change is near 0, that's going to happen, but of the 33 sector predictions over the last 3 years, only 6 have been under +/-1000. I saw the same thing when I was valuing a construction company at the brokerage. The American Institute of Architects tries to predict construction activity, but their sector predictions are almost never with 10% of the actual number. We use these numbers because we don't think we have anything better. That doesn't mean they're actually good.

November 28, 2008

Newspaper Finance - II

The Balance Sheet

Put simply, American newspaper companies have too much debt, and have been fooling themsevles about how much equity they have. When they went through that period of consolidation a few years back, the surviving (so far) companies vastly overpaid for the properties they bought, thinking that either they could turn them around or that the names would translate into sales. Then they borrowed agains these "assets," and have thus robbed themselves of whatever flexibility they had.

Here are the assets of the seven companies we've been looking at so far:

The bars represent the total assets. The blue represents something called, "Goodwill," the red, everything else. Goodwill is, roughly speaking, the vigorish that you pay for a company. Essentially, according to accounting rules, you're not allowed to pay more for something than it's worth. What you pay for it is what it's worth. So if you pay $4 million for a company whose net assets are valued at $3 million, after the buyout you put down the extra $1 million as an asset called, "Goodwill." It can generously be interpreted as extra cash you think the property should generate over time.

But it's a guess, an estimation, and can also serve as a slush line item to hide the fact that you just overpaid by 50% for a name that isn't generating any ad revenue any more, but that People Trust. It used to be that Goodwill was amortized over a period of time. Now, it has to be re-examined as often as necessary, and written down as appropriate.

Let's take a look at what's going to happen, as accountants realize that if the New York Times can't sell ad space, neither will the Podunk Press they sunk $2.5 extra large into five years ago, and that all the Goodwill in the world isn't going to change the fact that Iowans are getting their news from here and their local advertising from here.

The other rule here, so basic it's been known since the Italian Renaissance as the Accounting Rule is that Assets = Liabilities + Equity. If I write down an asset, I also need to subtract a like amount from either liabilities or equity. Since Goodwill isn't exactly a loan, likely it'll come out of equity. Here are the Owners' Equity lines from these companies, before and after Goodwill is subtracted:

That's right, boys and girls. Four of these Titans of Type go from having positive equity to negative equity, meaning they owe more than their companies are worth. And this is a completely defensible assessment. Given the current market, and the likelihood of how these will develop, you can't sell that Goodwill on the open market, because people apparently have resorted to paying what things are worth.

Now all of these companies have some long-term debt, although the Washington Post company seems to have made an effort to pay its down to minimal levels. Typically, I don't want debt-to-equity to be more than about 1. I know, there was a time not so very long ago when investors liked leverage. Because after all, we'd always be able to refinance that, wouldn't we? But I was never comfortable with huge debt-equity ratios.

Naturally, the D-E are calculating including Goodwill. Here's what happens when you subtract the Goodwill from the equity, and recalculate:

Not much fun. Of course, four of them go from positive to negative, including USA Today, which looked safe. The Journal newspapers only edge up to 1.30, and the NY Times - whoa, there, Pinch! - run up from a safe-looking 0.75 to almost 3.2. Only the Washington Post manages to stay sober.

These companies have been fooling themselves about the state of their balance sheets, believing that they had better balance than they did, because they were counting on revenues that will never materialize.

Now, I know what you're thinking. Debt's ok if you can pay it. Well, as we'll see next time, that's a problem, too.

November 25, 2008

What Was That About the Oil Industry

Governor Ritter and too many legislators have been counting on the oil and gas industry to protect us against a recession. Note that these are the same people who argue against shale oil on the basis of Black Sunday a few decades ago.

Here comes the bad news your mother warned you about:

Energy companies are slashing operating budgets as Colorado's once-booming oil and gas industry struggles with plummeting commodity prices, a tight credit market and an uncertain regulatory environment.

Hiring freezes have been implemented in an industry that just six months ago struggled to fill open positions. The effects of the cutbacks are trickling to other companies, such as law firms that provide service to oil and gas operators.

News flash: it ain't just the law firms. It's trucking companies, hotels, housing, construction, pipeline companies, metalworking, logging, and everything else upstream from the hole in the ground. It's not just severance taxes, guys.

They'll base the budget on a cyclical industry, but won't allow it to grow to take advantage of the upturns.

November 21, 2008

Culture Clash

Politicians don't understand businessmen. And businessmen don't understand politicians. Each certainly fails to understand the game that the other is playing, and why they're playing it. It results in consistently unequal negotiations, where one side ends up getting scalped by the other.

Businessmen are in it to make money, but the entrepreneurs are also in it to build, to create, to do cool things. Politicians are in it to help people, but they're also in it to control, to exercise power, to dispense favors. For most of history, politicians had the upper hand, because wealth was tied up with the crown and with aristocracy, which was tied up with the government. Only in very rare instances - fleetinglly in industrializing England and France, and more durably in 19th and early 20th century America - was business able to run its own show.

It depends on whose turf they're playing on. Earlier this year, the academics and bureaucrats over at the Fed got snookered into heavily subsidizing JP Morgan's buyout of Bear Stearns. Morgan had to put up $1 billion, in return for which the Fed bought $26 billion or so of bad debt. The pressure was on, a deal had to be reached, we were told, and the government gave in.

Similarly here in Denver, aviation moguls have repeatedly played the Denver and Colorado governments over DIA. United Airlines got preferential treatment concerning gates, which prevented the expansion of Frontier and kept UA on life support, all the while shutting out new competition like Southwest and keeping fares high and choice low for Denver flyers. Later, Boeing led the governor and the mayor on a merry chase, playing them off against Chicago and Dallas for the right to host their new headquarters. And let's not even get started about Coors Field and Mile High II.

But it works the other way, too, and historically, it's been far more common. We got to build DIA, but the concession stands had minority and women set-asides. For some reason - can't for the life of me figure out how - Wilma Webb ended up with one of those set-asides.

And now, the Big 2.5 were on Capitol Hill rattling their tin cups, asking for our money to stay afloat. The price of this was to be a government oversight board of some kind. They they can't run a railroad, they seem to have problems running a bank, they sure as hell can't run a school system, they gave up trying to run the airlines, but they want an oversight board for auto manufacturers.

Then there are the health insurers who seem willing to sign the death warrant for their own industry:

Wall Street Journal: On Wednesday, the insurance industry's Washington trade group issued a statement saying it could accept new rules requiring companies to cover sick people, as well as healthy ones, as long as all Americans were required to have insurance, with subsidies for those who need them. The declaration by America's Health Insurance Plans is a switch from the industry's long-time opposition to rules that bar the common practice of weeding out customers who are likely to rack up too many bills.

...

National Review: Still, [Daschle] is unlikely to abandon the contention that decisions regarding what should or should not be available as a universal benefit to all Americans should be decided by an independent body of experts and wise men, not the marketplace or the political process. A powerful, unaccountable über-regulator of health care would be exactly what proponents of market-based health care dread.

Having demonized insurers for making money on their product, the government would simply rig the rules so that its "non-profit" share of the health insurance market steadily grew.

There's a chilling line from Atlas Shrugged, where the increasingly meddlesome bureaucrats tell the Midshipmen of Industry, "You wouldn't want us to tell you how to run your businesses now, would you?"

Indeed.

Progressively more intrusive. Progressively more expensive. Progressively more restrictive.

November 17, 2008

Worst Bailout Excuse Yet

On Friday, driving to Aspen for the weekend, I happened to hear Lou from Littleton (a host, not a caller, on KOA, who's actually from Detroit), argue for the automakers' bailout. His case? That attendance at the Lions games was so bad that the NFL was considering lifting its blackout policy there.

So instead of spending $25 billion to keep the UAW afloat for a few more years, how about the Lions just lower the ticket prices? Oh, right. Probably because then they wouldn't be able to put that quality product on the field that the people of Detroit have come to expect over the last 50 years.

November 12, 2008

PERA-lous Territory

Moral Hazards, everywhere you look. Arnold Kling has been all over that terrible idea, the proposed auto bailout.

A big reason that the auto industry is in trouble financially is that many of its current and past workers have retirement benefits (including medical care) that are defined benefits. That is, the benefits are promised regardless of whether enough money was contributed to provide for them.

And why is this a problem?

This refers to companies with defined-benefit pension plans, which are plans that promise to pay specific benefits, even if the funds in the plans lose money. The companies think that it is onerous that they should be expected to actually have to take steps to keep their promises. Instead, they want to go on as if everything is fine, and leave somebody else to pick up the tab if it isn't.

And who are the tab-picker-uppers? Naturally, the taxpayers, under the Pension Benefit Guarantee system.

Everyone who promises defined benefits thinks that somebody else needs to help them keep their promises. That somebody else is you and me.

First GM, and then PERA, which is less arguable, because those pushing this little piece of socialism will then claim that you and I made the promises to the government employees.

In fact, it's almost as though they're pushing to help GM in order to clear the way for a PERA bailout.

November 10, 2008

Blessed Are the Cheesemakers

October 25, 2008

Right to Work

Readers of the blog, and those following the campaign, know that I'm a fan of Right to Work, and therefore a proponent of Amendment 47.

I just saw an anti-Amendment 47 ad, claiming that Right to Work would both lower wages and cost jobs. I suppose these are truly bipartisan ads, in that neither Hoover nor Roosevelt seemed to think that employment had anything to do with the cost of labor.

October 10, 2008

Special BTR Today

I'll be doing a special noon-time BTR show today about the financial crisis with King Banaian of SCSU Scholars, and William Polley of, ah, William Polley.

Hopefully, we'll all learn something.

July 31, 2008

How a Campaign is (and isn't) Like a Startup

As a result of the campaign, I've been invited to chat with the local IDEA Cafe, basically a support group for aspiring and recovering entrepreneurs. Since it's a decidedly non-political group, I'll be talking about process, rather than policy. Basically, a campaign is a startup, and the campaign and entrepreneurs probably have a lot to learn from each other.

How so?

Well, for one thing, you had better have done your research before you start running. Your product is a combination of positions and proposals. (To some extent, your product is also your positioning relative to other candidates, but more about that later.) If you think you're going to have time to do research and refine the product once the campaign is underway, good luck with that, as they say. Part of a campaign is working on and refining message, but the basic product, and the principles underlying it, had better be settled before you start to run.

Probably the piece of the campaign that people are most familiar with is the marketing aspect - segmenting the market, and then trying to position yourself into (and your opponent out of) favor with those juicy segments. Here's where your brand - i.e. party - can either help or hurt. Trying to get yourself in front of as many voters as possible also matters, and there are free forums and so-called earned media that are less available to entrepreneurs, by virtue of the process.

And then, there's funding. Like any good enterprise, a campaign needs to show the prospect of a return on an investor's money in order to raise funds. And like any good pie of investors, the target group can be divided into more and less risk-averse. The great risk-takers will help fund the petition drive. But many folks won't contribute until you're past the primary.

Here again, the value in funding a candidate can vary from race to race. An investor in a candidate in a safe district might be seen as looking for access once the person's elected. A contributor in a close race is looking to boost that party's prospects for control. A candidate in a more difficult district can still raise money by broadening the theater: after all, votes in his district count towards state totals on things like ballot initiatives and Senate and Presidential races. And every candidate can sell the longer-term, multi-cycle business of fighting the battle of ideas in the trenches.

And then there's the Exit Strategy. Campaigns usually have a series of well-defined exit strategies; they're called, "elections." Although, if you think of the operation in terms of a political career, and not just one campaign cycle, then it more closely resembles and ongoing operation. The problem is that way, way too many candidates and politicians do exactly that...

Continue reading "How a Campaign is (and isn't) Like a Startup" »

December 6, 2007

CFA'd Out

Which is just as well, because the exam was Sunday.

The exam pass score is a 70, which is tougher than it seems, especially when you realize that only 40% of the examinees pass the thing. For some reason, the CFA Institute hasn't deigned to sign a contract with a computer testing center. I was able to get my brokerage licenses more or less at will, since I could take them on the computer and have them scored immediately. The Level I, despite being multiple choice (or multiple cherce, if you're from Brooklyn), uses those little pencil-bubble sheets that tolerate neither stray marks nor incomplete fills. The Level II is essay question, and to keep the monks in shape for that, they have them grade the Level I by hand and I should know in about 5 weeks whether or not I passed. So the monks can have time off for Lent, and also watch the World Series, they give the Level I twice a year, then pick the best, most reliable monks, and have them grade the Level II and the Level III in June only.

Now I know that I either passed or failed on my own merits. No pulling a Baltimore Ravens and blaming the refs if I failed. But there are a couple of points to make. First, about the econ section. The MBA program I attended neither required nor taught econ. And the econ study book (provided by the CFA Institute itself) was noticeably lacking in sample questions on the subject. This is a real problem, since a great deal of words in economics jargon mean more or less the exact opposite of their common, everyday dictionary definitions.

Now the CFA does provide sample exams. At $50 a pop. Naturally, I bought all five, so I could trade 'em with my CFA pals. They're on line, they grade them right there for you (apparently the monks are too busy at Matins), and tell you what sections you need work on. But then, they disable the browser's Print and Select-All functions, even though they only let you take each exam once. For $50, you would think they'd understand that you want to take them home, so you can take them again and again. Of course, you can still do a View-Source and paste them into a text file, then edit them to allow printing, and print them from the browser.

Not that anyone would actually do that. Oh no. Of course not. Cough.

The sample exams are actually helpful. They advertise them as having real questions from past exams, and then it turns out that they have real questions from the exam you're about to take, too. There's no question that going back over the tests a few times drilled into my head the right answers for somewhere between 10 and 20 questions.

In any case, the worst thing you can do is to go back and start figuring out the answers to the questions you remember. That way lies madness. So here I sit, checking out job listings with more attentiveness, hoping that I'll be signing up for the Level II in June, rather than the Level I again.

October 19, 2007

Business and Baseball

So Manny Ramirez doesn't think it's the end of the world if the Bosox don't win the pennant this year. As usual, Manny's a little, what, isolated? out-of-step? oblivious? to the desires of the Red Sox nation. So yesterday, Mike Greenberg explained that fans want their players to care as much as they do, especially if they're making more in a year than most will make in a lifetime. And Mike Golic explained that it just doesn't work that way, that it's a job, and that getting paid more doesn't make you care more. We've heard it all before.

Then Greenberg said something like the following, and I'm paraphrasing:

Fans forget that for people inside sports, it really is all about the money. Sports is the only industry where what the customers want has nothing to do with what the owners want. Owners and players want to make money, while the fans want to win. Take our company, Disney. Do moviegoers care if they make a movie that wins the Oscar? No, not really.

Greenberg makes a mistake than many sports commentators make, when commenting about sports-as-business, and in doing so he lands himself completely on the wrong side of the discussion.

Let's point out first that successful teams make more money. With the exception of the Los Angeles Clippers, few teams can lose and continue to make money year after year. Getting taxpayers to build you a new stadium is a one-time boost, but eventually people get tired of watching a lousy product, and there are plenty of free places to see the mountains from. There's a reason the Braves left for Milwaukee, and the Expos are now the Nationals, replacing two previous DC baseball teams.

One reason the Yankees, Red Sox, Redskins, and Celtics are worth what they're worth is decades worth of building fan loyalty through winning. Championships. (Don't quibble with me about the Red Sox. They went to the World Series at least once a decade since the Babe was a bat-boy.) The A's obviously have better attendance and make more money since figuring out how to manage a budget and value-invest in players.

Bill James points out in his brilliant 1988 essay, "Revolution," that the competing business entities here aren't really teams, they're leagues. Except for a narrow swatch of Connecticut, the Yankees and Red Sox don't really compete for fans the way they do for wins. But MLB competes with the NFL for attention (also known as brosdcast revenue), and the Rockies compete with the Avs and Broncos and Nuggets for local attention. The reason the NHL #6 and sinking fast is that its games are on something called the "Vs." network, not because they Avs win or don't win.

While the Yankees may hate the Red Sox and the Cowboys may hate the Redskins, from a business perspective they need each other, like the black-white/white-black guys on that Star Trek episode. Because otherwise it's just the Black Sox throwing around a ball on a cornfield in Iowa.

James makes the insight that Greeny misses entirely: I buy a can of tomato soup because I want tomato soup. Just because Campbell's sees it as a business doesn't mean I have to. They may have better soup, or more flavors, or they may have better packaging, or more convenient sizes, or placement deals with Safeway. For them, that's business. Me, I just want a can of soup.

Baseball is selling competition. The minor leagues withered away into mid-inning diversions because of TV, yes, but also because their competition isn't real. The players care about stats because they want to get to the next level. Just like the managers. For them, success isn't winning an International League championship, it's getting called up to the majors and watching their old mates win that title.

When major league players don't care, or are perceived as not caring, it damages the honesty of the competition every bit as much as Giambi on the Juice. If enough players don't care, then the fans won't, either. They'll look for a league or a sport where players do care. And those players and owners will make the money.

October 11, 2007

Leading With Your Chin

So I'm sitting here, listening to KNUS, when on comes an ad for CITGO gasoline.

"We bring you a steady stream of Venezuelan oil..."

It's not often you hear an advertiser openly and honestly give you the best reason for avoiding their product like the plague, hoping they'll shrivel and die.

And on KNUS, Salem Radio, which isn't exactly a target market filled with warm fuzzies for Herr Hugp.

August 27, 2007

Receivables Securitization

Over at the Three-Letter Monte, the CFA Blog, I have a posting discussing securitization of accounts receivables, and its location within the Statement of Cash Flows. I'm not sure this is a particularly widespread problem, but it may well be a more serious one for certain companies.

Here's the issue. Some companies have gotten into the habit of packaging their receivables and selling them off at some discount to a buyer. You know those ads where Orson Bean asks you why you should have to wait for a settlement or a lottery annuity? Well these companies apparently feel the same way. So they collect the money now from a third party, buy their hambuger, and then pay the third party back next Tuesday when their customers pay them.

Typically, companies will publish a schedule of their receivables, if not how long they're outstanding, then how long they expect them to be. This gives the purchaser some idea of the historical collections record, how long they can expect to take to collect what's outstanding, and how much they might expect to have to write off.

The buyer could take an annuity, some percentage of the receivables over time, or some percentage at the beginning. Any of these arrangements can be considered borrowing at some interest rate. As a result, they should be listed on the statement of cash flows under financing cash flows. But because the revenue is secured by receivables, which are part of operating cash flows, many companies categorize them there.

Now, the notional interest rates some of these companies pay will rise, if they can find buyers at all. Their operating cash flows will shrink, and valuations based on those cash flows will fall substantially. In fact, there's reason to suspect that those companies that place this financing under operations are the ones that are most likely to need the cash.

Next step: find a list of such companies.

August 24, 2007

The Modern Lyceum Movement

The Wall Street Journal carries a fawning review of one of my favorite companies, The Teaching Company, the modern incarnation of the Lyceum Movement. The length of the lectures and the level of engagement required is pitch-perfect. I've had particular luck with the music courses and the history courses, but the only reason the literature courses haven't worked as well is that I rarely have had time to read the books.

The bus ride has been devoted to CFA studying, in fact it has become a primary reason for taking the bus when I can. Although come to think of it, that course on Byzantium is probably the ideal accompaniment to floor tiling.

August 20, 2007

The Weekend

Sunday was Chore Day. All day. For the first time since the sod went it, I cut it. Naturally, it was so high that the lawnmower kept cutting out. So I'd cut a few inches, back up, cut a few more inches, back up, etc. It was like cutting grass with a battering ram. Sometimes, I would restart the mower, and it would cut off just as I set it down. After 90 minutes out there in the sun, I can't begin to describe what a patience-building exercise that was. As for the grass, it's in good shape, but I can see where I'll want to fertilize as soon as I can.

After that, it was Back To The Tile. I've laid all the center tile, the tile I don't have to cut. Now, it was time to cut the edge tile. Break out the wet saw! Woohoo!

It was more tedious than hard. Since I was off just slightly from square to the walls, and since the walls themselves are off slightly from square, I had to measure each tile to cut separately. Down to measure, grab a tile, set the saw, and push it through. I will say that I've gotten pretty good at guiding a tile through by hand, without the guide, cutting along the pencil line. You have no idea how useful that is when you need to shave the tile down by 1/16", or just the width of the blade. And so, after four hours of turning all that tile back into clay (think ceramic dust + water), the edge tile is done, except for the pantry area. Not laid down permanenetly, but placed to measure. Pictures to follow soon.

Sunday evening was wall-to-wall wall-themed bumper music, in honor of our imported disingenuous lefty blogger, as opposed to the homegrown kind. My personal favorite was "Cry Me a River" by singer Kathy Wall, but there's plenty to choose from.

So what about Friday afternoon?

Well.

What happens when you naively believe that Sprint will simply do what they say, and exchange the phone at a store? Exactly what I should have expected from a company who only promised to exchange the phone in the first place to make up for lousy customer service. What should have been a 20 minute exercise turned into an hour ordeal.

I walked into the store, waited a few minutes for my turn, and then explained to the salesman that customer service had promised to exchange my phone. No dice, I was told. I needed to go to one of their newly consolidated Customer Service stores for that. And here's a handy map to help you find them!

I extended the salesman the courtesy of arguing with him briefly, then put the map back on the pile with all those other maps, and asked for his manager.

< Rod Serling Voice >Mr. Cole, sales manager of Store #506 at Cherry Creek North. Mr. Cole is a quiet, unassuming young man, just starting to make his way in the world. He earns a large portion of his compensation by making sure that no exchanges take place in his store. Little does he suspect that he is about to place a call to...the Twilight Zone.< /Rod Serling Voice >

In short order, I am told by Mr. Cole that, 1) he can't exchange the phone because he's not a service center, 2) he can't call customer service because 3) he won't have access to my account records, 4) there will be a $55 service charge at the service center for exchanging the phone, and that customer service won't be able to waive the charge.

That's four whoppers in only a few minutes. I informed Mr. Cole that I had no intention of arguing with him longer than it would take for me to drive to the Park Meadows service center, and that I had no intention of driving to the Park Meadows service center. No luck. As I was ready to walk out of the store, I went back, got his card, and called customer service from my phone.

Long story short - he called customer service himself (2), brought up my records on his computer (3), exchanged the phone (1), and had them reverse the service charge on my account (4). Short on time, I refrained from asking Mr. Cole what he had accomplished by stonewalling, since he did everything, anyway.

This is clearly the result of some insane incentive system that Sprint has set up. I'm sure I've mentioned this before, but Omni magazine had a story about 25 years ago, maybe a little longer, about a game where government bureaucrats compete to see who can most frustrate and enrage the citizenry foolish enough to show up at their offices. Sprint must offer very large prizes to the winners.

August 13, 2007

Customer Service

The weather's still muggy, but now the monsoons are a little less reliable. So now, it's the triple threat: heat and humidity, and you still have to run the sprinklers.

Apparently, the Sprint-Nextel merger isn't going so well. I went to the Sprint website to pay the bill, and found that while Sprint may have known who I was, Sprint-Nextel had apparently come down with corporate Alzheimer's and I had to re-register. All of which went fine. Except they have you enter your password, and your Social Security Numberin the clear. Apparently, it hasn't occurred to the people who run the company that someone might try to use their wireless internet card to pay their bill, you know, in a public place.

Then, the dreaded, "Double Secret Probation Security Question." You get to choose your question, so I picked, "First Elementary School." Answer: Mosby Woods. Evidently, whatever software, and I use that term advisedly, they're using to run this website, thinks that a space is a special character, which rules out something like half the schools in the country. "Street where you grew up" isn't much better, but since the name of that street was "Northwood-that's-one-word-northwood," I took it.

You get a confirmation text message, enter the secret code telling you to drink Ovaltine, and you're resgisered! Here's the text of the message I got:

Subject: --- Put the subject of the mail here ---

---Put the body here and put a 'VqBvGKmk' where the validation code goes----

How these people survived Y2K without routing all of our calls through Russia is a deep, deep mystery.

So, I decided to call customer service, figuring that of all companies whose bills I could pay by phone, the phone company would be one. Guess again.

Remember that sketch where Mike Nichols tries to get a phone number from Elaine May? This was about the same. *4, Account Information, wanted a PIN, and cut me off when I couldn't remember it. *2, Customer Service did the same, but referred me to *3, Bill Pay.

Which also required the PIN Which Cannot Be Named. And this time, finally, I got to talk to a real person. Who asked for the phone number. And my name.

And the PIN.

It took rounds with two other customer service people before I found someone who could override the damn computer and take the payment for my bill. Yes, remember? They were sufficiently determined not to take my money that they turned what should have been a five minute job into a half-hour adventure.

People, if anyone reading this is in charge of customer service, don't do this.

July 30, 2007

CFA Blog

I mean it this time. After a couple of fits and starts, I'm going to take the Level I exam in December, and I'm going to be blogging about the studying.

A few starter posts to get things going...

April 28, 2007

Fooled by Randomness

I've recognized myself in Nassim Taleb's superb Fooled by Randomness. Taleb has disdain for reporters, whose job it is to fit facts, post-hoc, into a coherent story. And he's right.

I cover a company called Brush Engineered Materials, BW. Take a look at that chart, especially the last day.

Several weeks ago, I had gotten a call from a reporter at the Cleveland Plain Dealer who was working on a story about the company. Thursday was the Company's earnings call, and while they met their own guidance, many analysts (although not I) had expected them to beat them. The stock dropped 10 points. The story was scheduled to run Friday, and I got a post-close from the reporter, his editor explaining that they couldn't run something about the company and ignore a 17% drop in the price.

I said,

"Investors just got a little over-enthusiastic," said Joshua Sharf, a stock analyst with Wm. Smith & Co. in Denver. Thursday's stock close "is where Brush was a couple of weeks ago, probably about where it should be. People are disappointed," he joked, "that earnings didn't exceed their expectations."

In retrospect, this is exactly the kind of post-hoc explanation that does nobody any good. In the morning meetings, I never speculate on where a stock's going thast day, week, or month. I have a price target. If I like the stock, I like the stock. If I don't, I don't. But I - along with Taleb - have exacty no idea where the market or an individual stock is going that day, and it's silly to try to explain it after the fact.

In the future, when asked by a reporter why a stock is dropping, I'll probably say something like, "Who the hell knows? More sellers than buyers, I guess."

April 27, 2007

I, Voice Mail

I have just finished arguing with a voice mail system.

I was calling UPS. I have two books on order, scheduled to arrive at the office today. But the last scan is from last night, and it's the check-in scan to the warehouse in Commerce City. So I wanted to call, to see if it were on the truck, and if it weren't to do as I had done before and drop by the warehouse and pick the thing up for myself.

Ha.

First, the voicemail asks me what it can do for me. (Heh.) It lists 4 items, beginning with "Track a Package."

Me: Customer Service

It (Slightly peeved at having been interrupted, and been asked for an item not on the menu): That's ok, and I can connect you with a customer service agent, but first, select one of the four options, "Track a..."

Me: Track a package

It (Breathing a slight sigh of relief): Please say your tracking number

Me (Breathing a slight sigh of annoyance): 1Z 189 093 04 505 38 HS

It: (Tells me what I already see on the web tracking screen)

It: Now, what else can I do for you? Track a package, ...

Me: Customer Service

It (Clearly annoyed at being asked to interrupt someone's coffee break): I can connect you with a customer service agent, but that is the most recent information available on your package. Would you still like me to connect you with a cusomer service agent? If so, say, "yes."

Me: Yes.

It: If so, say, "please."

No, I made that last part up, but you see where this sort of thing could lead you. I remember a science fiction story in Omni many years ago, about a game played by bureaucracies. The purpose of the game was to get the public very, very upset. Points were awarded on the basis of how ticked off individuals got, and how out of control they behaved. The real purpose of the game was to discourage public interaction by discouraging the public from showing up at all. I believe the beta version of the game is being tested now at various DMVs around the country.

Conference Call Etiquette

Earnings conference calls usually go on too long as it is.

Here's a suggestion.

When a conference call caller - like, say, an analyst - begins his call with, "Well guys, I really don't know what to say," the call moderator should disconnect him and tell him to get back in the queue when he figures it out.

March 26, 2007

Dallas

Another month, another business trip, this time to Dallas.

Now I know what you're thinking, and I was surprised, too, but it actually looks like a pretty decent place, at least the bits I've seen so far.