Archive for category Budget

Forty Years of PERA

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on March 13th, 2013

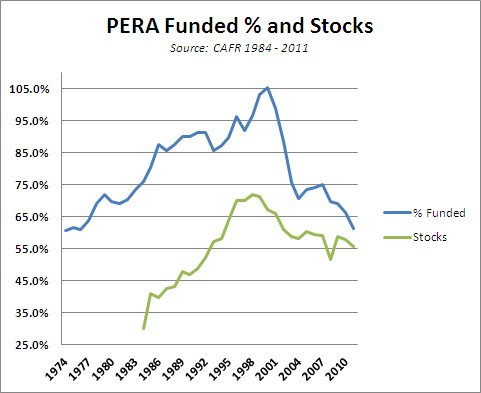

We’ve been here before with PERA. Sort of. Most people following the issue remember that in 2000, PERA was over 100% funded, and that its funding ratio has fallen steadily since then. What they don’t know is that back in 1974, PERA was woefully under-funded, at about the same 60% funded ratio that it is now. It took advantage of the long bull market to pull itself out of that situation:

Note that as the funded ratio rose, so too did the percentage of the portfolio allocated to common stock (both domestic and foreign) rose, as PERA basically decided to let the bets ride, rather than re-allocate to maintain the lower-risk portfolio. When the bubble burst, they ended up paying the price for having stayed too long at the fair. Now, PERA has returned to a somewhat more conservative allocation strategy, targeting 25% of its money for fixed income, and a target of 58% in stocks. Nevertheless, this is a far cry from the 45% or so in bonds that they held up until 1992 or so, and the nebulous “Alternative Investments,” which includes things like venture capital (and in which I’ve included the Lumber investments), suggests that PERA is still chasing yield there:

So this just puts us back where we were before, right? We climbed out of this hole before, we can do it again.

Not so fast. First, as noted before, PERA’s in a less aggressive portfolio now than it was in 2000. This is a good thing, since it takes out some of the volatility from its portfolio. But it also means that it probably can’t count on a run of good luck to lift it out of unfundedness the way it did last time. Also, as we’ve previously noted, the fall from grace in 2001 and 2002 wasn’t just a matter of poor returns, it was also a matter of increasing liabilities with more generous benefits. That hasn’t gone away.

And not all 60% funded ratios are created equal. Here are PERA’s inflation-adjusted, per-capita unfunded liabilities since 1974 (constant 1983 dollars):

On a per-capita basis, the overhang is about 4x what it was in 1974. So in fact, we’re in much, much worse shape than we were 40 years ago when this roller-coaster ride began.

Public Pensions and Real Returns

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, PPC on March 4th, 2013

In the discussion on public pensions, there’s been a great deal of focus on the projected rate of return. I’ve posted on what I think is PERA’s optimistic 8% here, and on the fact that that’s actually an improvement from the 8.75% that they were projecting as recently as 2002. That said, for pension estimates, their inflation assumptions matter as much as their raw return assumptions. The actuarial consequences of poor inflation estimation are too much to summarize here. But even on the basic question of returns inflation matters: the real return on an investment is the nominal return minus inflation.

Over the last 10 years, public pensions have gotten some credit for modestly reining in aggressive growth assumptions. PERA, for instance, has moved from a 8.75% growth assumption to 8%, and CalPERS has made similar adjustments. Overall, the average growth assumption has dropped slightly from 8.04% to 7.86%. But the average inflation assumption for public pensions nationally has dropped from 4.0% to 3.31%. This means that instead of decreasing the real return assumption has actually gone up from just over 4% to just over 4.5%.

For the record, PERA’s inflation assumption was dropped from 4.5% to 3.75% in 2003, where it has stayed. Both the investment return and inflation numbers are higher than the national average and national median, though.

I don’t really think that the inflation numbers here are unreasonable. And my problem with PERA’s 8% return assumption goes beyond the average itself – 8% has been the historic return on stocks, and doesn’t take into account the additional volatility and risk that come with higher return. But it’s clear that PERA and other plans have been dining out on their flexibility on returns, while the increase in real expected returns goes unremarked-on.

The disconnect also highlights the price we’re going to pay – in accuracy, and eventually in dollars – for using the rate of return as the discount rate. Interest rates are closely tied to expected inflation, and here the funds themselves are admitting that the gap between the rate of return and the proper discount rate has been growing.

PERA – More Retirees, Fewer Workers

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, PPC on March 3rd, 2013

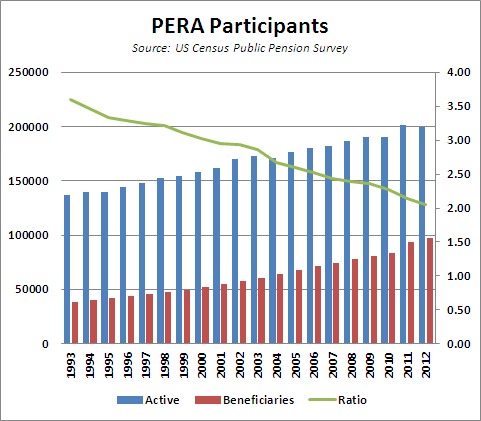

This chart is more or less self-explanatory. Over the last 20 years, the number of workers per beneficiary within PERA has dropped from about 3.6 to just over 2.0:

PERA’s CAFR includes the following disclaimer:

By itself, a declining ratio of actives to retirees and beneficiaries does not pose a problem to a Division Trust Fund’s actuarial condition. However, to the extent that a plan is underfunded, a low or declining ratio of actives to retirees and beneficiaries, coupled with increasing life expectancy, can complicate the Division Trust Fund’s ability to move toward full funding, as fewer active, contributing workers, relatively, are available to amortize the unfunded liability.

This is about right, although even a fully-funded system won’t stay fully-funded for very long under these conditions. Indeed, PERA was fully-funded as late as 2001. In the 90s, PERA’s long-term problems were masked by a tech bubble, and when that burst in 2000, the fund started to fall into an under-funded state that it’s never recovered from. Since under an underfunded defined-benefit plan, current expenses have to be paid for out of current contributions, and fewer workers are pulling the cart for each retiree, the deficient horsepower will have to be supplied by the taxpayers.

The Higher-Ed Bubble, In One Chart (and one article)

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Education, PPC on February 16th, 2013

Rep. Mike Coffman took a lot of heat for suggesting that perhaps it was time to re-evaluate these priorities, with his words being distorted into an attack on the liberal arts in particular, and higher education in general. Turns out he was onto something.

- Sociology

- Fine Arts

- Education

- Religious Studies/Theology

- Hospitality/Tourism

- Nutrition

- Psychology

- Communications

Just for grins, I looked up how many of CU’s undergraduate degress over the last quarter-century (well, since 1989), have been awarded in these majors:

For fun, I added in almost anything with the word “Studies” in it, and that’s what the percentage line (right-hand axis) shows.

Peaking at just over one-third of all bachelor’s in 2004, over 30% of all undergraduate majors are still in these low-return majors. The dropoff occurred between 2004 and 2008, but has since – astonishingly – stabilized since the popping of the housing bubble, when job prospects for graduates have almost never been worse. Students are taking on crushing burdens of debt to graduate with these degrees.

You and I will be subjected to sob stories about how Colorado is under-funding its higher education. Instead, perhaps we ought to be taking a closer look at what we’re funding.

Is Legislative Stinginess to Blame for PERA’s Problems?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Finance, PERA, PPC on January 28th, 2013

One of the favorite tropes of PERA apologists runs like this: PERA was fully-funded in 2001 or so, at which point the state legislature began failing to make 100% of its Annual Required Contribution (ARC). It was then that PERA’s funded level began to drop off. Therefore, if the state legislature had fully-funded the ARCs, today, PERA would not face a massive unfunded liability.

It’s a rhetorical masterstroke, redirecting blame for the current situation on a stingy state legislature that put PERA last in its priorities. And while grounded in a grain of truth, it severely understates and misattributes the nature of PERA’s financial crisis-in-the-making.

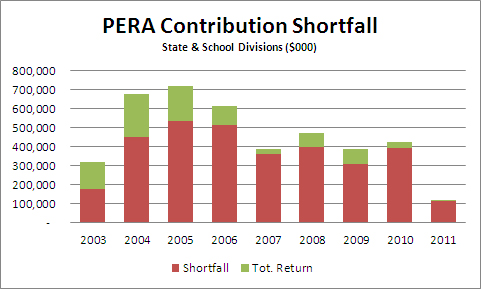

The grain of truth is this: the state legislature, beginning in 2003, began to under-pay its Annual Required Contribution. Of course, this affects not only the immediate year, but all future years going forward. Not only is the money from the shortfall not there, but the accumulated return on those dollars aren’t there, either. For this post, I’m just going to focus on the two largest divisions, the School Division and the State Division. They were combined in 1997, and separated again in 2006, so I’ll consider them as a unit.

Here are the yearly shortfalls, along with their future values to the end of 2011 (the latest year for which we have data). The first year for each underpayment is dollar-cost-averaged, so we give half the year’s return, and full yearly returns thereafter:

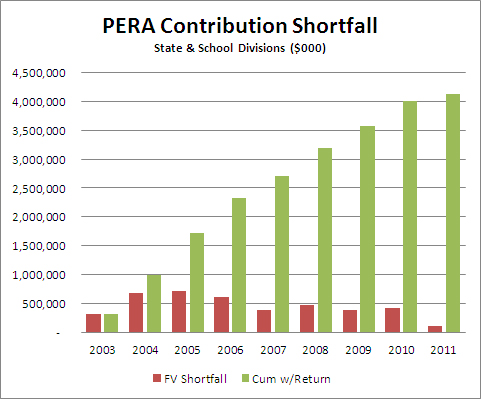

For 2003, the legislature underpaid by about $177 million, costing about $142 million in future returns, for a total effect in 2011 of $319 million. If you add up the total effect, year-by-year, you get the following result:

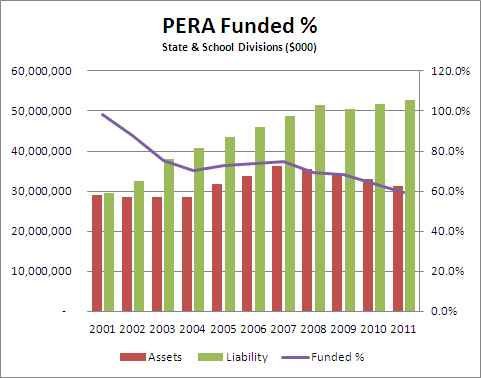

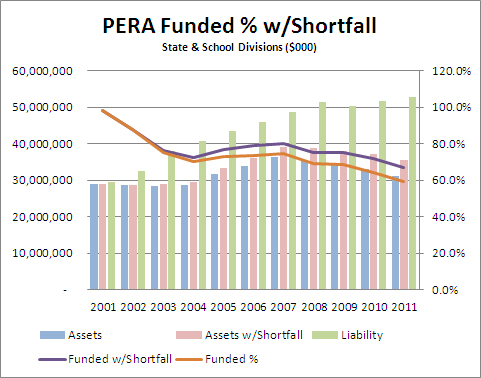

So by the end of 2011, the cumulative effect of 9 years’ worth of funding shortfalls is a little over $4 billion. The argument by PERA hinges on the fact that it’s at 2003 that PERA began to be underfunded:

As you can see, though, PERA was already suffering from poor 2001 and 2002 returns, even though there was no shortfall from the state those years. What did increase substantially was the size of the liability; the size of the assets actually held steady. From 2004 to 2007, solid returns managed to keep the dollar amount of the gap from growing. But then 2008 hit, and the size of the obligations continued to increase even as the fund got clobbered in the market. The liability dropped as a result of certain stop-gap changes that were made in 2009, but has since resumed its upward march, even as the actuarial value of the divisions’ assets has continued to fall.

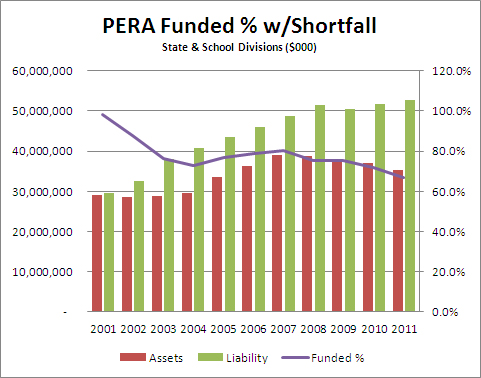

Would it have made a difference if the state had made good on its entire ARC for 2003-2011. The answer is yes, but not very much. Adding in the cumulative shortfall each year, here’s the effect on the assets and the funded ratio for the State and School Divisions:

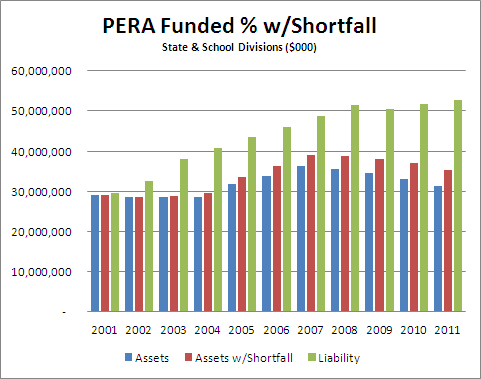

Despite some increased, they’re still seriously underfunded. Since it’s difficult to see the difference between the two charts, I’ve made the comparisons here. First, the difference in assets:

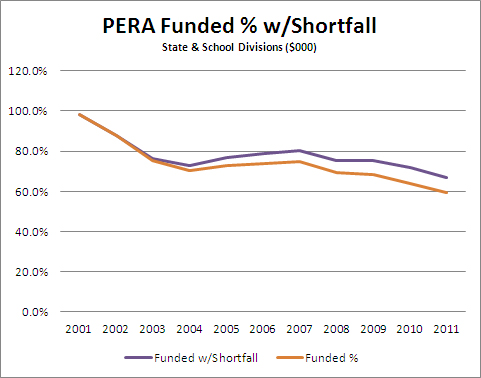

An increase of total assets from $31 billion to $35 billion is not nothing, as they say down at the station, but it’s also not nearly enough to start to close the gap with liabilities. So little that the difference in funding ratio barely moves the needle:

For those of you who want it all on one chart, possibly for optical exams, here it is:

In reality, it’s worse than this. Prior to 2006, PERA didn’t report a sensitivity analysis on its assumed rate of return, so we have only the values for 8%. If we assume a more realistic 6.5% return going forward the unfunded liability grows from $25 billion to about $40 billion, and the extra $4 billion makes even less of a dent.

PERA isn’t suffering from a legislature that isn’t keeping its promises, it’s suffering from having made promises it can’t keep. And it’s the very PERA members who are going to get hurt the most, the ones who’ve been sold a bill of goods about what’s waiting for them when they retire.

Lowering the Hill

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on January 23rd, 2013

Ultimately, large changes will be needed to keep PERA solvent. But little changes can have an effect, too. Today, the state House Finance Committee will be hearing HB13-1040 from Republican Rep. Kevin Priola:

Current law averages the 3 highest annual salaries of a member of the public employees’ retirement association (PERA) when calculating that member’s retirement benefit amount. The bill increases the number of highest annual salaries used from 3 to 7 for anyone who was not a member, inactive member, or retiree of PERA as of December 31, 2013.

In 2010, SB1 changed some rules to make it more difficult for employees to suddenly spike their salaries and other compensation at the ends of their careers, in order to game the system and maximize their PERA benefits. For instance, for benefit calculation purposes, raises and other increases in compensation – like saved vacation being cashed in – were limited to 8% in any given year. Employees could receive larger raises, but benefits could only be calculated on the first 8% of the increase.

This bill would make it even harder to game the system by averaging the highest seven years’ compensation instead of the highest three. It’s a reasonable measure, and it would only apply to employees who join PERA after the end of this year. The Democrats enjoy a large majority on the Finance Committee, so they may well kill the bill. But the fact that it got assigned to the Finance Committee at all, rather than relegated like SB13-055 to the State, Veterans, and Military Affairs Committee, makes the outcome less certain.

Democrat Sen. John Morse Follows Familiar Pattern On PERA Reform

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on January 23rd, 2013

The state Democrats, led by State Senate President John Morse (D-Colorado Springs), are continuing their deeply unserious approach to Colorado’s massive unfunded PERA liability this session. Incoming Speaker of the House Mark Ferrandino (D-Denver) had already indicated as much, first by characterizing those who would seek to deal with the problem as wanting to use the economic situation as an excuse to take away public employee’s pensions, and then by appointing Lois Court (D-Denver) as Chairman of the House Finance Committee.

The latest sign comes with respect to a bill proposed by Republicans Sen. Kent Lambert of Colorado Springs and Rep. Lori Saine, a freshman Republican from Dacono. The bill, SB13-055, would require PERA to use the state’s long-term borrowing interest rate as the discount rate for its liability, and would require that the CAFR be released by May 31 of each year. It would also require that contribution and/or benefit levels for any individual fund be adjusted when the amortization period for that fund climbs beyond 30 years.

All of these are eminently reasonable proposals. For reasons discussed before, the discount rate should be the required rate of return of PERA’s investors, the members. There is also no real reason why PERA can’t produce a CAFR within five months of the end of the calendar year; those dates have been slipping in recent years, but the fact is, the bulk of the CAFR is boilerplate or easily-written text, and the same financial statements and charts each year. And since the stated goal of PERA is to be within a 30-year amortization window, requiring them to be so would simply put teeth into an existing target.

Yet Sen. Morse has chosen to assign the bill not to the Senate Finance Committee, which has jurisdiction over PERA oversight, but to the State, Veterans, and Military Affairs Committee. That committee, often referred to as the “kill committee,” is traditionally staffed with the most partisan members of both parties, and used to kill inconvenient bills. Often that’s because “no” votes on the bills might be embarrassing to the majority, perhaps sufficiently embarrassing that some members wouldn’t be able to resist the temptation to vote for them.

That Senate President Morse has chosen to put this bill in front of the kill committee is practically an admission of its common sense, and his lack of it, but it does make clear the two halves of the Democrats’ full-court defense of their public employee clients’ pension plans.

First, they’ll protect them from any votes they might lose, and also protect the House and Senate Finance Committee members from having to cast “No” votes they’ll later have to explain.

Second, both Ferrandino and Morse have claimed that 2010’s SB1 “solved” the PERA problem for good, though tremendous liabilities remain, even given the plan’s own overly-optimistic assumptions and accounting practices. That will be their explanation for dodging these votes, but even if true, it’s a non sequitur. If PERA is truly fixed, surely members of the committee charged with its oversight would not only be the best-informed of that fact, but also best able to explain it to constituents. Putting the bill in front of a committee whose actual charter has nothing whatsoever to do with PERA, and whose reputation is one of chief enforcer, can’t inspire much confidence that the Democrats will be dealing with the state’s financial problems in good faith in the next two years.

The Hill Gets A Very Little Less Steep – For Now

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, PPC on January 22nd, 2013

One of the main points of contention about PERA has been the expected rate of return. Up to 2001, PERA used an expected rate of return of 8.75%, but lowered that to 8.5% from 2002-08, and again to 8% in 2009, where it now stands.

So how has PERA done since 2001, when it stood at a 100% funding level? The chart below shows the annual return over those 11 years for which they’ve reported, plus an estimated return based on a similar portfolio from CalPERS, the California pension plan. CalPERS has a .99 correlation with PERA, which is about as close to metaphysical certainty as anything human gets. In 2012, CalPERS reported a 13.26% return, which would project a 13.9% return from PERA, so just for grins, I’ve plugged that into the 2012 spot.

The red line is the running CAGR from 2001, or Cumulative Average Growth Rate for 2001 through the current year.

As you can see, over time the red line becomes less volatile, as more years are factored into the average.

The green and purple lines are where it gets interesting. Those lines are the return that PERA would have to see over the remainder of the 30-year window from 2001-2030, in order to meet the 8.75% and 8% targets. So, for instance, after 2007, in order to have a CAGR of 8.75% from 2001-2030, PERA would have to have returns of 9.3% from 2008-2030.

Note that using the 8% return from 2001 basically gives hindsight credit to PERA, since in 2001 they were projecting 8.75%, not 8%. Let’s blow up that part:

As you can see, PERA started out with poor 2001 and 2002 returns, which put it in an immediate hole. Even good returns from 2003-2007 only got the required returns down to 9.3% and 8.3%, respectively. Then 2008 happened. By now, we’re 12 years into that 30-year window, and even a good year like 2012 will only push the required return down a little bit, about 0.3%. For instance, it would take 7 years of 15% returns to get the required return for the 8.75% line down to below 8.75%, in effect, to catch up to the 8.75% projection, and it would take 5 more years to catch up to the 8% projection. It’s highly unlikely that even 5 years will pass without a normal, cyclical recession, and attendant lower returns.

The average return is 6.28%, the CAGR is lower, just over 5%. In fact, any set of returns with an average of 8%, but which are not actually 8% each year, will compound to less than 8%, making it that much harder to make up ground. Bear that in mind when someone talks about how easy it is to make up for a couple of bad years.

All of this argues for using a Monte Carlo simulation to determine solvency, rather than a simple rate of return. Such a model is a little more expensive to run, but will give a far more accurate picture of the health, or lack thereof, of any defined benefit plan.

PERA – It’s All For The Kids

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Education, PERA, PPC on January 20th, 2013

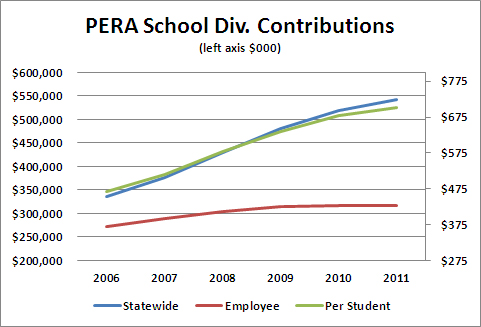

Not all school spending is for the kids. A lot of it is for the teachers, at the expense of the kids. Over the last five years, even as school districts and teachers unions complain that per-student spending has been “slashed,” “cut to the bone,” or “eviscerated,” per-student spending on the PERA School Division has been growing well beyond inflation. Here are the per-student contributions by the major local school districts (minus Denver, which has its own PERA division), and statewide:

Over the least 5 years, this has translated to growth rates well in excess of inflation:

And who’s been picking up the tab? The Employer contribution has been growing far in excess of the Employee contribution in absolute terms. The employer contribution has been growing at 10% per year from 2006-2011, while the Employee contribution has grown at a 3% rate over the same period. The overall per-student increase has been just under 8.5%.

Not only is PERA taking money from the classroom, it’s taking taxpayer dollars from the classroom at a wildly disproportionate rate. Is this what the teachers unions mean by “shared sacrifice?”

PERA’s Resolute Optimism, Part 2

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 9th, 2012

In the previous post, I mentioned that PERA, in retaining its 8% expected rate of return, was persisting in an unwarranted optimism, one that is likely to end up costing the citizens of Colorado billions of dollars down the line. Part of the evidence was that other municipal pension plans around the nation have recently lowered their expected rates of return. That said, as of 2009, the overwhelming number of plans in the Center for Retirement Research’s Public Plans database were living in what can only be described as Fantasyland, as the following histogram shows:

I’m sure the right part of the graph, which resembles a strong signal from those plans to their taxpayers footing the bills, is only accidental.

In fact, between 2001 and 2009, plans were extremely reluctant to revise their expected rates of return, despite the fact that they rarely met them for more than a year at a time, and continued to fall farther behind in their funding. If you look at actual returns for those years, they don’t come anywhere close to what was projected:

The result is that plan assets haven’t kept up at all with plan liabilities, even in these years when the market has performed reasonably well (Source: Public Fund Survey):

Understanding that many factors go into whether a plan’s funded level increases or decreases, the fact is that looking forward from 2001 to 2009, over the succeeding 21 years, the median plan would have to return about 10.5% over the following 21 years, to make up for having fallen behind in the first decade:

The problem, of course, is that plans have spending requirement every year; they can’t simply choose to sit on their assets and wait for their investments to catch up. It means that low returns in early years require even higher returns in the later years for the plans to return to 100% funded levels, without increasing cash infusions or a reduction in benefits.

One guess as to which will be the plans’, the governments’, and the SEIU’s first choice.