Archive for October, 2017

PERA and the 30-Year Amortization

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA on October 25th, 2017

In its campaign to sell its proposed reforms the PERA board has taken to emphasizing that the 30-year amortization period is written into Colorado statute. Per C.R.S. 24-51-211:

(1) An amortization period for each of the state division, school division, local government division, judicial division, and Denver public schools division trust funds shall be calculated separately. A maximum amortization period of thirty years shall be deemed actuarially sound. Upon recommendation of the board, and with the advice of the actuary, the employer or member contribution rates for the plan may be adjusted by the general assembly when indicated by actuarial experience.

Not only did they mention this at the Aurora tour stop last week, they tweeted it out last night.

The less rigorous standard means they never actually have to achieve full funding. PERA’s appeal to the authority of the law in this case rings hollow.

It’s the industry standard for public pensions, which is why it was written into the law in the first place. Presumably, if the industry standard were to change, the statute would change as well. Legislators aren’t experts in this material; they were clearly relying on the recommendations of the public pension stewards at the time. In effect, PERA is appealing to its own authority in this matter.

The fact is, industry standards for public pensions haven’t saved the industry from its problems. Not so long ago, the industry standard was a rate of return well over 8%. Right after SB1 was implements, PERA’ amortization periods all dropped under 30 years. That lasted all of one year.

The choice of a target amortization period should be based on whether or not it makes sense, not on appeals to authority that have proven less than authoritative over the years.

Photo Credit: Todd Shepherd

Breaking News from 1800

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Uncategorized on October 23rd, 2017

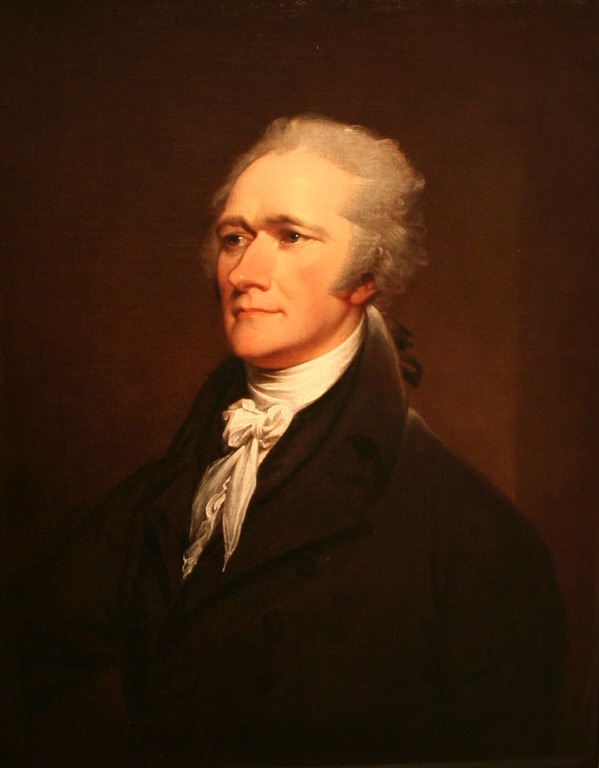

In 1800, in the midst of a contentious presidential election, Alexander Hamilton decided that the future of the Federalist Party was too important to be left in the hands of John Adams. In order to promote his own candidate for Federalist electoral votes, Hamilton issued an anti-Adams broadside cataloging the shortcomings of Adams as president. Chernow assesses the screed as one of the worst of Hamilton’s political miscalculations.

That it was partly also driven by personal grievances, though, doesn’t change the truth of some of the charges, or that they echoed much of the popular sentiment around Adams’s performance in the job. Many of the weaknesses of the Adams presidency may sound familiar to observers in 2017, even though the book was written in 2004.

Beyond the unenviable task of succeeding Washington, Adams had several handicaps to overcome. Despite long years in politics, he had never exercised executive power at the state or federal level. And he detested political parties at a time when America was being torn asunder by factions. As president, Adams was the nominal head of the Federalists, but yet he dreamed of being a nonpartisan president….During his presidency, Adams was often stranded between the Federalists and the Republicans and accepted by neither. It was to prove a rare case in American history of the president hesitating to function as the de facto party leader. — p. 523

He had retained his cabinet from the second Washington Administration. But even as he found himself frequently publicly at war with them, he refused to fire them until late in his term. It was certainly true that Hamilton exercised some influence over the individual cabinet members, in some part because he bothered to engage them rather than dictate to them from afar during his frequent absences in Quincy.

Washington had always shown great care and humility in soliciting the views of his cabinet. Adams, in contrast, often disregarded his cabinet and enlisted friends and family, especially Abigail, as trusted advisers. His cabinet members found him aloof and capricious and prone to bark out orders instead of asking opinions. — p.524

Adams, having held over for too long subordinates with no personal loyalty to him, or ideological loyalty to his program, whatever than might have been, found himself stuck with no good defense of his leadership, and so found himself putting out several mutually inconsistent but self-serving versions, simultaneous arguing that people were working to undermine him, and that he was actually in control and playing a higher-level game the whole time:

John Adams told two stories of his presidency that never quite jibed. In one, he claimed to be an innocent bystander, long oblivious of Hamilton’s influence over his cabinet members. He had no idea until the end, he said, that they were receiving guidance from his foe; when he belatedly discovered the plot, he moved swiftly to purge the culprits. In another version, Adams claimed that he had known all along that Hamilton controlled the cabinet, because he had already controlled it under Washington… — p. 524

And Hamilton’s pamphlet drew heavily on anonymous, inside sources – the cabinet members themselves – who were concerned about Adams’s temperament and suitability for the job.

[Treasury Secretary Oliver] Woolcott considered the president a powder keg. Of Adams, he told Fisher Ames, “We know the temper of his mind to be revolutionary, violent and vinditive…. [H]is passions and selfishness would continually gain strength.” …At moments, however, Woolcott grew ambivalent about the idea of Hamilton exposing Adams, arguing that, “the people [already] believe that their president is crazy.”

Thus, in his massive indictment of Adams, Hamilton drew on abundant information provided by McHenry, Pickering, and Woolcott about presidential behavior behind closed doors….Stories about Adams’s high-strung behavior, if legion in High Federalist circles, were little known outside of them. Hamilton also wanted to stress the mistreatment of cabinet members, lest readers dismiss his critique of Adams as mere personal pique…

Yes, the Republic survived both the mutual enmity of protean political parties, and the chaotic behavior of the often-absentee Adams. But that was at the beginning of our Constitutional framework, when we were still working out how the presidency and parties would work. (And even then, one could argue that parties didn’t survive this first attempt. The Federalists pretty much collapsed after the 1800 election, leaving no effective opposition to Jefferson’s Republicans. Madison was widely blamed for a terribly destructive and unpopular War of 1812, but the mediocrity that was James Monroe won two terms virtually unopposed, anyway.)

The point is that by now, we’re a world power, still the wealthiest nation on earth, responsible for maintaining freedom of the seas and some level of global stability. That we’ve reverted back to some of the inchoate quality of our early political development does not necessarily bode well for the coming decades, possibly the coming century.

Hamilton’s Productivity

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History on October 22nd, 2017

In his biography of Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow marvels several times of Hamilton’s capacity for work. He wrote the bulk of the Federalist Papers, sometimes turning out as many as 5 in a week. When his opponents in Congress wanted to try to hang him on unfounded corruption charges, for instance, they demanded that he produce voluminous reports on short deadlines. They underestimated him. On p. 250, Chernow describes how Hamilton was able to do this:

Hamilton’s mind always worked with preternatural speed. His collected papers are so stupefying in length that it is hard to believe that one man created them in fewer than five decades. Words were his chief weapons, and his account books are crammed with purchases for thousands of quills, parchments, penknives, slate pencils, reams of foolscap, and wax. His papers show that, Mozart-like, he could transpose complex thoughts onto paper with few revisions. At other times, he tinkered with the prose but generally did not alter the logical progression of his thought. He wrote with the speed of a beautifully organized mind that digested ideas thoroughly, slotted them into appropriate pigeonholes, then regurgitated them at will.

Both the organized mind and the regurgitation are harder than they look. They both require patience, training, and discipline. Yes, he was writing at a different time, when repeating arguments didn’t mean chewing up half of your allotted 700 words. Length was never an issue, and Hamilton, being Hamilton, was brilliant enough that neither was publication or readership. But I notice it when favorite columnists of mine no longer have anything new to say, and part of my own lack of production is from a desire to say something new each time, rather than even mentally cut-and-paste from previous efforts. Contrary to popular opinion, it takes patience to repeat yourself.

This goes hand-in-hand with having an organized mind. One wants to be able to assimilate events and ideas, and to respond to them. But there’s a concomitant risk of building a system and fitting everything into that system. One’s thinking becomes rigid, rather than supple and responsive. You see this all the time with people who reduce all political arguments to one or a handful of principles – everything becomes confirmation of those few underlying ideas, but then all arguments return to those same few ideas. Discussions become stale, because it’s more comfortable to have the discussion you’re used to having.

Breaking News From 1798

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Political History on October 18th, 2017

I may be the last person on the planet to have read Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. I’ll certainly be digesting it for a while.

Among Chernow’s contributions is a detailed discussion of the American political climate, during the Washington and Adams administrations, when the bulk of Hamilton’s contributions to the nascent government were made. It’s also when we saw the emergence of the first real political parties in history, parties committed to more than the mere attaining and retaining of power, but also to rival economic and political theories.

Today, we’re used to the stability of the two-party system, but at the time, they were not only a novelty, but a bit of a shameful one at that. The Founders had wanted to avoid factions, or parties. The new parties were not only organized around ideas, but also around the personalities of their leaders. This led to a curious combination of personal touchiness, mutual misunderstanding and hostility, and denial that it was going on at all.

From Pages 391-92 of the softcover edition:

The sudden emergence of parties set a slashing tone for politics in the 1790s. Since politicians considered parties bad, they denied involvement in them, bristled at charges that they harbored partisan feelings, and were quick to perceive hypocrisy in others. And because parties were frightening new phenomena, they could be easily mistaken for evil conspiracies, lending a paranoid tinge to political discourse. The Federalists saw themselves as saving America from anarchy, while Republicans believed they were rescuing America from counterrevolution. Each side possessed a lurid, distorted view of the other, buttressed by an idealized sense of itself. No etiquette yet defined civilized behavior between the parties. It was also not evident that the two parties would smoothly alternate in power, raising the unsettling prospect that one party might be established to the permanent exclusion of the other. Finally, no sense yet existed of a loyal opposition to the government in power. As the party spirit grew more acrimonious, Hamilton and Washington regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature.

One last feature of the inchoate party system deserves mention. The emerging parties were not yet fixed political groups, able to exert discipline on errant members. Only loosely united by ideology and sectional loyalties, they can seem to modern eyes more like amorphous personality cults. It was as if the parties were projections of individual politicians – Washington, Hamilton, and then John Adams on the Federalist side, Jefferson, Madison, and then James Monroe on the Republican side – rather than the reverse. As a result, the reputations of the principle figures formed decisive elements in political combat. For a man like Hamilton, so watchful of his reputation, the rise of parties was to make him ever more hypersensitive about his personal honor.

The parallels between the politics of that day, when parties were being formed, and today, when they have been structurally weakened and are in flux, should be obvious. The party establishments and the administrative state mitigate some of the effects, but there’s no question that election laws have neutered party back-rooms and allowed anyone to run under a party banner. The move towards open primaries further erodes party discipline. Each party increasingly sees the other less as principled opposition and more as a conspiracy bordering on organized crime. And there is no question that the Bush and Clinton dynasties, along with the personally prickly Obama and Trump, have personalized presidential politics to a degree we’ve not seen in a while.

Over the last several presidential elections, people have called attention to the vitriolic nature of political campaign rhetoric, if not (until 2016) by the candidates themselves, then by their surrogates and supporters. As often, people have trotted out some of the truly vicious things said in the campaign of 1800. With a somewhat broader view, that similarity seems less a coincidence and more like the product of a common cause.