Archive for category Political History

The Democrats’ Assault on Free Speech Continues

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, National Politics, Political History on November 17th, 2020

Joe Biden has selected Richard Stengel to head up state-owned media for his transition team. This includes overseas media such as Voice of America and our Middle East Broadcasting Networks.

Stengel was an Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs under the Obama Administration. Apparently, his big takeaway from that post was that the First Amendment’s free speech protections, being unique in the world, are deeply and profoundly flawed.

For some of us, American Exceptionalism is a feature. For the likely incoming administration, it is a bug. In the case of Stengel, it’s clear that he doesn’t even understand how the First Amendment protections of speech are supposed to work. He mocks that, “…the Framers believed this marketplace was necessary for people to make informed choices in a democracy. Somehow, magically, truth would emerge.”

There’s nothing magic about it, and there’s no guarantee that “the truth” will always emerge. Indeed, there’s no guarantee that there is a truth to emerge. The Founders believed, instead, that the government was a terrible vehicle for determining what speech was acceptable and what speech wasn’t. Anyone empowered to make those decisions would inevitably put his thumb on the scale, and a government empowered to do so would use that power to silence opposition.

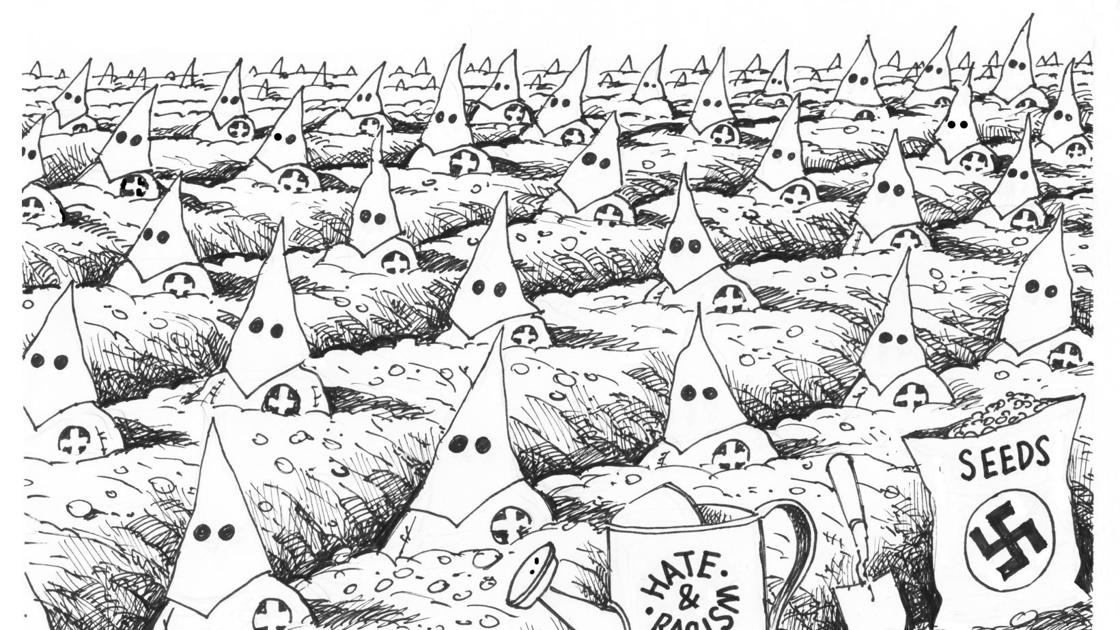

For those of you on the other team, before you cheer too loudly, consider the possibility that you may not always be the ones defining “hate speech.” Along those lines, it is worth considering what will likely not qualify as “hate speech.” The Democrats consistently opposed extending Article VI protections under the Civil Rights Act to Jews, and consistently opposed adopting the IHRA definition of Anti-Semitism. I would oppose a “hate speech” exception to the First Amendment even if the Democrats had not reflexively opposed President Trump’s attempts to extend civil rights protections to Jews, however. Special protections extended can be special protections retracted, and even the threat to do so could be used to extract political concessions. That’s the point.

Many of us voted for Trump out of self-defense, to protect ourselves against the use of the government to attack us or censor us for our political or social opinions. Many of us were quite clear about that before the election. This sort of thing is exactly why.

Breaking News From 1798

Posted by Joshua Sharf in History, Political History on October 18th, 2017

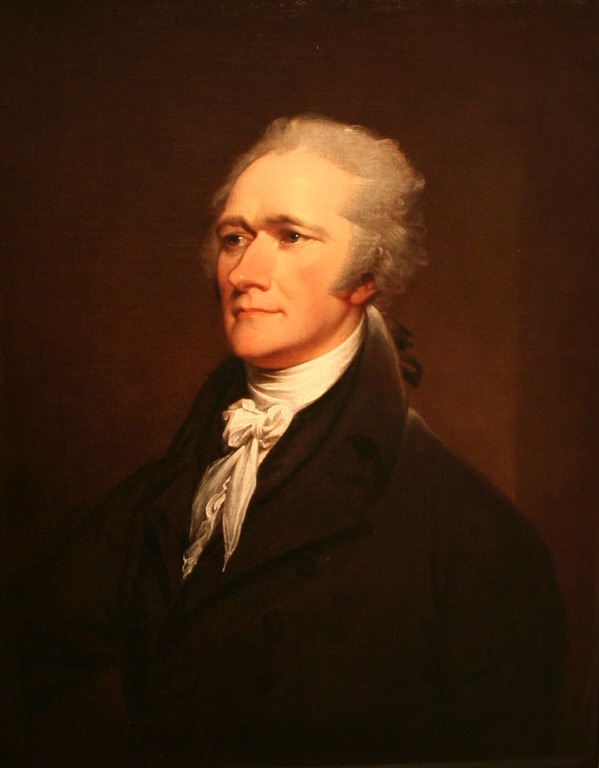

I may be the last person on the planet to have read Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. I’ll certainly be digesting it for a while.

Among Chernow’s contributions is a detailed discussion of the American political climate, during the Washington and Adams administrations, when the bulk of Hamilton’s contributions to the nascent government were made. It’s also when we saw the emergence of the first real political parties in history, parties committed to more than the mere attaining and retaining of power, but also to rival economic and political theories.

Today, we’re used to the stability of the two-party system, but at the time, they were not only a novelty, but a bit of a shameful one at that. The Founders had wanted to avoid factions, or parties. The new parties were not only organized around ideas, but also around the personalities of their leaders. This led to a curious combination of personal touchiness, mutual misunderstanding and hostility, and denial that it was going on at all.

From Pages 391-92 of the softcover edition:

The sudden emergence of parties set a slashing tone for politics in the 1790s. Since politicians considered parties bad, they denied involvement in them, bristled at charges that they harbored partisan feelings, and were quick to perceive hypocrisy in others. And because parties were frightening new phenomena, they could be easily mistaken for evil conspiracies, lending a paranoid tinge to political discourse. The Federalists saw themselves as saving America from anarchy, while Republicans believed they were rescuing America from counterrevolution. Each side possessed a lurid, distorted view of the other, buttressed by an idealized sense of itself. No etiquette yet defined civilized behavior between the parties. It was also not evident that the two parties would smoothly alternate in power, raising the unsettling prospect that one party might be established to the permanent exclusion of the other. Finally, no sense yet existed of a loyal opposition to the government in power. As the party spirit grew more acrimonious, Hamilton and Washington regarded much of the criticism fired at their administration as disloyal, even treasonous, in nature.

One last feature of the inchoate party system deserves mention. The emerging parties were not yet fixed political groups, able to exert discipline on errant members. Only loosely united by ideology and sectional loyalties, they can seem to modern eyes more like amorphous personality cults. It was as if the parties were projections of individual politicians – Washington, Hamilton, and then John Adams on the Federalist side, Jefferson, Madison, and then James Monroe on the Republican side – rather than the reverse. As a result, the reputations of the principle figures formed decisive elements in political combat. For a man like Hamilton, so watchful of his reputation, the rise of parties was to make him ever more hypersensitive about his personal honor.

The parallels between the politics of that day, when parties were being formed, and today, when they have been structurally weakened and are in flux, should be obvious. The party establishments and the administrative state mitigate some of the effects, but there’s no question that election laws have neutered party back-rooms and allowed anyone to run under a party banner. The move towards open primaries further erodes party discipline. Each party increasingly sees the other less as principled opposition and more as a conspiracy bordering on organized crime. And there is no question that the Bush and Clinton dynasties, along with the personally prickly Obama and Trump, have personalized presidential politics to a degree we’ve not seen in a while.

Over the last several presidential elections, people have called attention to the vitriolic nature of political campaign rhetoric, if not (until 2016) by the candidates themselves, then by their surrogates and supporters. As often, people have trotted out some of the truly vicious things said in the campaign of 1800. With a somewhat broader view, that similarity seems less a coincidence and more like the product of a common cause.

From the Convention Floor

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2016 Presidential Race, Political History on June 15th, 2016

Almost forgotten in the other storylines of the 1968 Democratic Convention was the two-hour boomlet (or so it seemed) to run Ted Kennedy in place of his assassinated brother, Robert. Theodore White recounts the moment (p. 351-354), noting that it was briefer, more fleeting, and far less likely than the press coverage that Tuesday evening made it seem. Kennedy would never allow himself to be seen actively courting such a movement, and the forces needed to make it happen were too unlikely as allies.

Almost forgotten in the other storylines of the 1968 Democratic Convention was the two-hour boomlet (or so it seemed) to run Ted Kennedy in place of his assassinated brother, Robert. Theodore White recounts the moment (p. 351-354), noting that it was briefer, more fleeting, and far less likely than the press coverage that Tuesday evening made it seem. Kennedy would never allow himself to be seen actively courting such a movement, and the forces needed to make it happen were too unlikely as allies.

He then delivers, in a footnote, his damning indictment of the press and its coverage of that non-development:

It has always seemed to me unfair to criticize the floor reporters of television for behavior forced on them by the commercial competition of their networks. To report a convention from the floor, the networks choose their best political correspondents…Turned loose in the compact space of the convention floor, with dozens of Governors and Senators, scores of Congressmen, political bosses, old contacts and political freshmen, they are as happy as dogs in a meat market. No one can escape their cameras and microphones; nor do many delegates want to escape a televised interview…

Delegates thus lived in an echo chamber; and so, as a matter of fact, did the reporters themselves. Floor reporters are turned loose on a chase, and the director in the control room calls the course, the story-line they must chase. On the convention floor, someone can always be found to say anything, and it remains only for good direction to put the fragments together in dramatic form. Neither the delegates nor reporters can be blamed; only the mechanism and its programming, which calls for competitive and rival drama to hold audience.

If the script that night had called for the discovery and dissemination of a Southern revolt, or the candidacy of Lester Maddox, the reporters could have delivered that to the nation, too – all carved out of truth, from the lips of authentic and honest men on the floor.

This is something to bear in mind as we head towards Cleveland, with Trump’s poll numbers beginning to tank and his fundraising outlook getting bleaker. There will be reports of incipient revolt, of blocs of delegates withholding their support, of Rubio and Kasich (who retain control over their delegates) trying to organize Cruz delegates to deny Trump the nomination on the first ballot.

With the increasing likelihood of violent events taking place outside the hall, and the necessity of word-of-mouth organization of the delegate inside the hall, things have changed less than people think, even with the advent of social media. We’ve seen how those media are highly susceptible to the manipulation of a very few influential practitioners with many followers.

Add to that the fact that, unlike in Chicago in 1968, the press will be actively looking for stories designed to make the Republicans look bad. Certainly, the press’s favorite story-line already is the failure of the party to unite. They will find ample fodder for that claim, and any other they decide they need on Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday evening.

Caveat emptor.