Archive for category Constitution

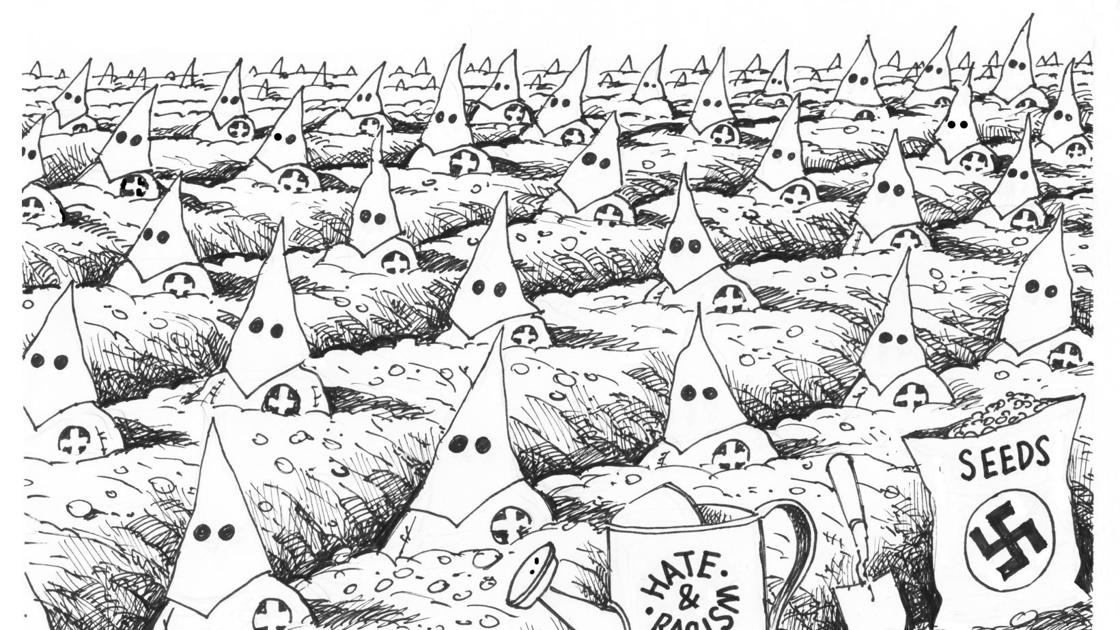

The Democrats’ Assault on Free Speech Continues

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, National Politics, Political History on November 17th, 2020

Joe Biden has selected Richard Stengel to head up state-owned media for his transition team. This includes overseas media such as Voice of America and our Middle East Broadcasting Networks.

Stengel was an Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs under the Obama Administration. Apparently, his big takeaway from that post was that the First Amendment’s free speech protections, being unique in the world, are deeply and profoundly flawed.

For some of us, American Exceptionalism is a feature. For the likely incoming administration, it is a bug. In the case of Stengel, it’s clear that he doesn’t even understand how the First Amendment protections of speech are supposed to work. He mocks that, “…the Framers believed this marketplace was necessary for people to make informed choices in a democracy. Somehow, magically, truth would emerge.”

There’s nothing magic about it, and there’s no guarantee that “the truth” will always emerge. Indeed, there’s no guarantee that there is a truth to emerge. The Founders believed, instead, that the government was a terrible vehicle for determining what speech was acceptable and what speech wasn’t. Anyone empowered to make those decisions would inevitably put his thumb on the scale, and a government empowered to do so would use that power to silence opposition.

For those of you on the other team, before you cheer too loudly, consider the possibility that you may not always be the ones defining “hate speech.” Along those lines, it is worth considering what will likely not qualify as “hate speech.” The Democrats consistently opposed extending Article VI protections under the Civil Rights Act to Jews, and consistently opposed adopting the IHRA definition of Anti-Semitism. I would oppose a “hate speech” exception to the First Amendment even if the Democrats had not reflexively opposed President Trump’s attempts to extend civil rights protections to Jews, however. Special protections extended can be special protections retracted, and even the threat to do so could be used to extract political concessions. That’s the point.

Many of us voted for Trump out of self-defense, to protect ourselves against the use of the government to attack us or censor us for our political or social opinions. Many of us were quite clear about that before the election. This sort of thing is exactly why.

Some Short History Reading Lists

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Civil War, Cold War, Constitution, History, Revolutionary War on January 21st, 2018

We were over at a friend’s house for lunch this Shabbat. Knowing that 1) I have a lot of history books, and 2) I tend to read them, he was kind enough to ask me for some reading lists about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Cold War. “I haven’t had much luck with fiction, so I’m trying to round out my history.”

Here’s what I sent him. These aren’t intended to be college syllabuses, or comprehensive. They’re books that I have and leafed through, or that I’ve read. I’ve tried to vary them by author. I could have had the entire Revolutionary War list by Joseph Ellis, the whole Civil War list by Bruce Catton, but what’s the fun in that? My library, while large by 19th Century standards, is limited by the size of the house. Had I fewer books, I would paradoxically have more room for them. But it’s a good list, enough to cover some key points, get an overview, or just when your appetite for more.

American Revolution

For a decent overview of the war as a whole, Liberty by Thomas Fleming isn’t bad. I think it was originally written as a companion book to a PBS series, but it’s good in its own right. For a deeper examination of the issues around the Revolution and the war, and how the Founders handled them, American Creation by Joseph Ellis is recommended.

We all know of Washington Crossing the Delaware; David Hackett Fischer has written a great in-depth review of the events surrounding that crossing and subsequent battles, and how they set the stage for the rest of the war, in Washington’s Crossing.

And for well-researched discussions of adoption of the two primary founding documents – the Declaration and the Constitution, Pauline Maier’s American Scripture and Ratification give surprising insights into what people were thinking at the time.

The Founders lived on into the post-Revolutionary era, and had a second act right after the Constitution in 1787, so some bios are in order. Richard Brookheiser’s short Founding Father is a fine thumbnail bio of Washington; for something longer Ron Chernow has bios of both Washington and Hamilton. And David McCullough’s John Adams is what the PBS series was based on.

Having come this far, read about 700+ pages about the early Republic, when were getting ourselves established, with Gordon Wood’s Empire of Liberty. I’m reading it now, and pretty much every chapter has some surprise or another.

Civil War

For the lead-up to the war, and how we got to the point of secession and war, William Freehling’s long, two-volume The Road to Disunion is among the best.

Much of the same material is covered in the first volume of Bruce Catton’s very readable and shorter three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War. These are The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat. I would recommend anything written by Catton on the Civil War.

Also excellent is Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson. As a guide to Lincoln’s war, what the events looked like from DC, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals is magnificent.

Cold War

This one is tougher, because it covers decades, not mere years, so the politics, military, and technology changed substantially from 1948 to 1989. I’ve picked out the books I have and have read that do a good job talking about the Cold War. My library is heavier on the spy stuff, but there was a lot of spy stuff.

Witness by Whittaker Chambers is indispensable. He starts out as a Communist, and then converts over to the good guys, and was a key player in one of the great Cold War controversies, the Alger Hiss case. Nixon’s rise to prominence began with this case, and the left never forgave him for being right.

The Great Terror, is one of the best books about Stalin’s Russia, by one of the best chroniclers of the 20th Century, Robert Conquest.

The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn is recognized as the best insider account of the Soviet punishment system.

Berlin 1961 by Frederick Kempe covers the building of the Berlin Wall.

Merchants of Treason by my friend Norman Polmar and KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents are old now, but a good guide to how to the KGB operated in the day, and how the Russians still operate today.

There’s also a vast literature of spy fiction, from Len Deighton’s devastating Game-Set-Match trilogy to John LeCarre’s oeuvre (start with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy).

That’s enough to keep you busy for a few years. So what are you still doing on this page?

Duck Dynasty, Free Speech, and Cable Unbundling

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, General, History on December 23rd, 2013

I’m not the first one to make the connection.

That’s not surprising. What is perhaps surprising is that we’re not the first generation to have the debate over what free speech means. In fact, the very first generation of free Americans had this debate. This same exact debate.

I read Pauline Maier’s remarkable Ratification in 2011, but this stayed with me. On p.71 – 75, she has a section on “Freedom of the Press.” Surprisingly, the context is very much the same now as it was 226 years ago.

Threats…encouraged writers to continue the standard practice of publishing essays under pseudonyms. In Boston, however, Benjamin Russell, published of the Massachusetts Centinel, announced in early October that he would print no essays that raised objections to the Constitution unless their authors left their names “to be made public if desired.” That would clearly discourage critics of the Constitution from speaking out. The local tradesmen and artisans (known as “mechanics”) who strongly supported ratification, “had been worked up to such a degree of rage,” one Massachusetts official noted, “that it was unsafe to be known to oppose [the Constitution] in Boston.” … Other commenters, however, charged Russell with violating freedom of the press since his policy would curtail the range of arguments available to the public. In Philadelphia, a writer who took the pen name “Fair Play” answered the threats leveled against those who criticized the Constitution by insisting “that the LIBERTY OF THE PRESS — the great bulwark of all the liberties of the people — ought never to be restrained” (although, he added, “the Honorable Convention did not think fit to make the least declaration in its favor”).

The freedom such writers defended went back to an earlier time, when colonial printers had to appeal to a broad range of readers to stay in business; they took a neutral stand and justified necessity by defining a “free press” as one that was “open to all parties.” That way of operating came under pressure as the market for newspapers grew and the Revolution raised doubts about giving “all parties,” including Loyalists, ready access to the reading public. State partisan divisions during the 1780s also made it difficult, and sometimes unprofitable, for printers to remain impartial. On the other hand, the establishment of a republic, in which all power came from the people, gave the argument for a press open to all parties a new ideological foundation: To exercise their responsibilities intelligently, the citizens of a republic had to be fully informed of different views on public issues.

That concept of a free press was, in any case, different from the standard Anglo-American understanding of “freedom of the press,” which referred to the freedom of printers to publish whatever they wanted without “prior restraint” by the government….The emphasis was on the freedom of the press to monitor and criticize persons in power and the policies they adopted.

…

In the end, proponents of the Constitution found an effective alternative to threats of tar and feathers and other forms of physical punishment: They could influence editorial policy by cancelling or threatening to cancel their subscriptions to “offending” newspapers. Advocates for freedom of the press could insist that the American people needed access to the full range of opinions on the Constitution. But were individual subscribers…obliged to pay for newspapers that published essays they considered profoundly subversive of their own and the country’s best interests?

…

Men like Oswald were rare. Only twelve of over ninety American newspapers and magazines published substantial numbers of essays critical of the Constitution during the ratification controversy…. If printers were “easily terrified into a rejection of free and decent discussions upon public topics,” [New-York Journal Thomas Greenleaf] wrote in early October 1787, the “inevitable consequence” would be “servile fetters for FREE PRESSES of this country.” Greenleaf promised to give “every performance, that may be written with decency, free access to his Journal.” For their persistence, Oswald and Greenleaf suffered verbal attacks, cancelled subscriptions, and threats of mob violence. Their insistence on maintaining what they understood as a “free press,” that is, one that presented the people with criticism as well as hallelujahs for the Constitution, helped start a widespread public debate on the Constitution, which they they kept going. (Emphasis added – ed.)

Just because the government’s not involved doesn’t mean it’s not a free speech issue.

Arguing over whether this is a legal or a strictly First Amendment issue is the reddest of red herrings. I suppose there’s some possibility that some judge will decide that if a baker and a photographer can be forced to provide services for gay weddings, then A&E can be forced to employ religious Christians, but absent that, it’s unlikely this will be decided through the courts. And certainly nobody on the right is calling for a return to the bad old days of the “fairness doctrine,” which wouldn’t apply here in any event.

For most libertarians and conservatives, that’s ok. But we can’t let it end with that. We can’t short-circuit them by dismissing them because there are no legal implications. As Mark Steyn points out, if we want civil society to be where these discussions take place, then we have to ensure that civil society is a place where we can actually have these discussions.

Right now, it’s difficult to tell A&E, and only A&E, that you’re unhappy with their editorial decisions, because if you want to buy A&E, you’re also forced to buy a whole package of other cable channels, not all of which are even owned by the same companies. The most effective way to enable us to hold A&E accountable is to unbundle these offerings, and allow me to choose, a la carte, what channels I want to receive. There’s a bill pending in Congress to do just that, and Canada has already taken that step.

In the end, even though there’s an excellent chance that unbundling will mean higher, rather than lower cable bills, it may be the best means of sending the market signals that prevent an enforced conformity. Right now, more channels just look like a dizzying array of sameness, with those channels of communication that “appeal to a broad range” of viewers, readers, or listeners, being dictated to by bullies who cannot stand to hear that someone disagrees.

Feet of Clay

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, History, National Politics on June 3rd, 2013

For the last few weeks, I’ve been working my way through Henry Clay: The Essential American. Such political biographies are inevitably histories of the times, and Clay’s times basically bridged the America of the early Constitution and the America just before the Civil War.

I may or may not have time for a longer, more thorough post on Clay, but I wanted to throw out a few observations, as Clay spends a few years at Ashland, recovering physically and financially in preparation for one last stint in Washington, after his defeat as the Whig nominee in 1844.

Clay was, by any account, a remarkable and remarkably intense politician. He was quickly elected Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, and then, on his first day in the US House, elected Speaker of the House there. Clay would revolutionize that role, taking the Speakership from a mostly administrative role to a center of political power. When he moved to the Senate, he would wield similar power there as a floor leader, even without the formal role of Majority Leader that we have today.

Because of his long Congressional career, we know Clay today as the Great Compromiser, remembering his roles in the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and the Compromise of 1850, both of which helped stave off disunion over slavery. Those are merely the largest, best-known of his compromises. He led successful compromises over the tariff (despite being a westerner, he favored a high protective tariff), and over a renewed Bank of the United States and internal improvements, the last two thwarted by presidents rather than Congress. These three aspects of his program comprised what he referred to as the American System.

For being almost 200 years old, the politics of the 1830s and 1840s is strikingly modern. Much of this is the result of Andrew Jackson’s populist revolution in American politics, but Clay’s and the Whigs’ response to it also resonates with today’s reader. For instance, in vetoing the recharter of the Bank of the United States, Jackson’s message essentially dodged constitutional questions, and boiled down to the fact that he didn’t much like banks. Clay thought that Jackson’s lack of intellectual coherence in his veto message would cost him politically in the Mid-Atlantic states, where the Bank was popular. He underestimated the populist appeal of Jackson’s message. It wouldn’t be the last time Clay misread the politics vs. the policy of an issue.

Clay also had to deal with the changing nature of presidential campaigning. While personally outgoing and optimistic, and a fine public speaker, he never really enjoyed or thought seemly the public appearances and speeches that marked presidential elections in the 1840s. And in the 1844 campaign, he never could get his fellow Whigs to understand the importance of a centralized party organization. Counting on the popularity of their program and ideas to carry the day, they narrowly lost to James K. Polk, whose Democrats better understood the politics of faction.

The Whigs also might well have won, had they been able to keep the focus on the economy. They had won handily in 1840 on that basis, although Harrison’s death and Tyler’s allegiance to Democrat, rather than Whig, ideas, cost them mightily as the public perceived them as unready to govern. But the party in power often controls the public agenda, and it was to Tyler’s benefit – until he dropped out – to bring Texas, and the inevitable conflict over slavery – to the forefront. It was the 1844 equivalent of running on a supposed “War on Women,” in order to avoid talking about a wretched economic record.

It was also in the 1830s that we start to see the philosophical differences that would define American politics from then on. The Democrats favored a strong executive – first pioneered by Andrew Jackson – while the Whigs really coalesced initially around resistance to what they saw as the usurpation of legislative priority. But it was the Whigs who favored a more nationalist policy, Clay’s American System – a central bank, protective tariffs, and federally-funded internal improvements. So it was possible for Tyler to resist Jackson’s executive power grab by joining the Whigs, and still oppose the Whig federal program.

Clay never would be president, despite being a perennial nominee or mentionee for decades. It’s entirely possible that this was for the best. His time at the State Department under John Quincy Adams was miserable. Clay always supported legislative supremacy, believing that the Constitution put Congress in Article I for a reason, and there’s no reason to doubt his sincerity on this point, or to believe that it was one of convenience. Had he been elected President, he would likely have found crafting legislative compromise more difficult from the other end of Pennsylvania Ave., since he wouldn’t have been in a position to control the process as thoroughly as he did from the floor or the Speaker’s chair. The Presidency has not been kind to those with a legislative, rather than an executive temperament.

A Wind-Assisted “Win”

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, History, Labor, National Politics, PPC on March 15th, 2011

In track and field, when a runner has the wind at his back, and records he sets don’t count. Of course, in track, the win is still fair, because all the runners run under the same conditions. With the press, it’s always uphill and against the wind for Republicans and Tea Parties, downhill and wind-assisted for Democrats and unions.

In a previous post, I put up a little retrospective of some of the more troubling behavior by Wisconsin public servants, aided and abetted by college students, Organizing for America, and the DNC. I doubt whether even Mike Littwin would be able to claim this as a “win” if most of the country had seen these events as they were happening. The national media, which goes out of its way, if necessary, to make up stuff about Tea Partiers, was rigorously careful not to expose the American public to these scenes.

What are perceived as heavy-handed tactics often have a way of backfiring. (In Pennsylvania during the Constitutional ratification convention, for instance, dissenting members of the convention fled the scene to deny the convention a quorum, and two of them had to be hauled back bodily to Independence Hall to get the 2/3 necessary for business. This, along with the refusal of the press to publish speeches critical of the Constitution and the refusal of the convention’s official journal to record all the speeches, forced the Federalists to tread much more carefully in succeeding states, particularly Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia.)

But they don’t usually backfire when the targets are unsympathetic louts.

Just to pick on Mike a little, the last lines in his column suggest that the DC Democrats might find the inspiration and spine to make bold entitlement reform proposals from the events in Wisconsin. This makes no sense. In Wisconsin, the Democrats were defending the insupportable and unsustainable status quo. Failing to deal with entitlements, as the President has failed to do, would be more in keeping with that strategy.

Ghosts of Constitutional Debates Past – Part IV

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, History, PPC on February 27th, 2011

Continuing to work my way through the Debates on the Constitution, at a languid pace, I came to this letter from James Madison to Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was, at the time, Minister to France, so had no direct role in drafting the Constitution. Madison’s main concern in the letter is federalism, and the division of powers between the states and the national government. The letter serves as a reminder that the work of a committee, even a Constitutional Convention, is a work of compromise. In particular, these paragraphs:

It was generally agreed that the objects of the Union could not be secured by any system founded on the principle of a confederation of sovereign States. A voluntary of the federal law by all members, could never be hoped for. A compulsive one could evidently never be reduced to practice, and if it could, involved equal calamities to the innocent & the guilty, the necessity of a military force both obnoxious & dangerous, and in general, a scene resembling much more civil war, than the administration of a regular Government.

Hence was embraced the alternative of a Government which instead of operating, on the States, should operate without their intervention on the individuals composing them: and hence the change in principle and proportion of representation. (Emphasis added.)

This is critical, because it means that while the states would have a say in the federal government, in the form of the Senate and the Electoral College, the federal government would have no say in the selection of state officers, nor a direct veto on state legislation. (Both of these options were considered.) It also, I think, affects our reading of the Tenth Amendment, adding weight to the notion that individuals have standing to challenge federal attempts to overstep their bounds.

Right now, the Supreme Court is considering such a case:

Surveillance cameras captured Ms. Bond stealing an envelope from Ms. Haynes’s mailbox and stuffing potassium dichromate in her car’s muffler. That led to federal charges of stealing mail—and violating criminal statutes implementing the international Chemical Weapons Convention, which the U.S. ratified in 1997. Ms. Bond, who in 2007 was sentenced to six years imprisonment, appealed on grounds that Congress lacked authority to punish her for the chemical assaults.

In Philadelphia, the Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied Ms. Bond the right to raise that claim, ruling that only state officials had legal standing to assert a 10th Amendment violation of their authority. When Ms. Bond appealed to the Supreme Court, the Justice Department abandoned the Third Circuit’s decision, conceding individual defendants were entitled to argue that they were charged under laws exceeding congressional power.

For the record, keep your eye on another moving part here: whether treaties are permitted to override Constitutional protections. This could mean that even if the US were to sign a small arms treaty of some kind, provisions that violate our understanding of the 2nd Amendment might not apply here in the US. This isn’t to imply that signing or ratifying such a treaty would be a good idea, or that the Court would agree with me, just that the Court’s decision on this case might signal its current thought on the matter.

Ghosts of Constitutional Debates Past – Part III

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, History, PPC on January 23rd, 2011

So, a couple of weeks ago, we left the Constitutional debate with William Findley’s detailed, 22-point objection to the document. The editors of the Library of America volume include a similarly detailed, point-by-point rebuttal, by an anonymous respondent under the pseudonym “Plain Truth.” Some of his responses are weak, others are off the mark, but other score some points, and it’s interesting to see which are which.

Two of the themes that evolved early on were the lack of a Bill of Rights, and the stability of the tension between the states and the federal government. While the concern is among the most serious, the argument here back and forth is among the weakest, in part because of the lack of historical reference points. The Dutch and the Swiss had federal republics, but they were small, and the great threats came from outside, not inside. The Roman Empire – always a point of reference – was more useful is worrying about the concentration of power in the executive, a completely different mal-distribution of power.

But the question of whether or not the tension between the states and the federal government could be maintained, or would eventually either consolidate or fracture the Republic, is one that has to be conducted almost entirely in hypotheticals. It makes for a debate that we can evaluate in retropect, but one which must have been frustrating for those who weren’t committed to one side or the other. The federal-state split also manifests itself in odd ways. One letter in opposition to the Constitution, a “Letter from An Old Whig,” argues that the amendment process is too cumbersome, and that either no amendments will ever pass, or the country will tear itself apart trying to pass them.

Oddly, the debate between Findley and the rebuttal on this point could be about slavery – but isn’t, at least not in the way we think of it later. Findley objects that Congress can’t ban the slave trade until 1808, and his respondent says that he agrees this is too long, but since the matter can’t be much worse than it is now, maybe at least by then it will be better.

The question of a Bill of Rights is rebutted with much the same logic that Wilson used in his original speech defending the new Constitution: it isn’t necessary, since we assume that Congress’s powers are exclusive, while state constitutions are inclusive. Findley’s objection isn’t that this is wrong, but that he doesn’t trust that the Framers really mean it, or that future generations will live by it. The debate over the Banks of the United States would show there was some real risk on this point, but even that debate was carried on with the assumption of enumerated power, that the burden of proof was on the Bank’s advocates.

And for you 2nd Amendment fans – and who among us isn’t a 2nd Amendment fan – there’s the response to Findley’s worries about a standing army. “Plain Truth” claims that a standing army shouldn’t be a concern, since every man is a member of a militia, and what standing army could pose a threat to that? For those of you who think that guns are only for personal defense, consider that long and hard.

Two other points about the tenor of the debate stand out, as well. There’s another letter from Cincinnatus which reads like a blog screed. The “Old Whig’s” letter starts off professing that he really wants to be persuaded of the Constitution’s goodness, at least as an experiment. It’s not apparent whether he’s sincere, or is the Revolutionary Era equivalent of a seminar caller. The “Plain Truth’s” point-by-point refutation reads like an expert Fisking. In short, this is what robust, healthy political debate looks like.

Ghosts of Constitutional Debates Past – Part II

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, History, PPC on December 27th, 2010

In Ghosts of Constitutional Debates Past, I looked at some of the things that Centinel, aka Samuel Bryan, objected to in the Constitution, and how some of his projections about how power might migrate away from the original plan seemed to parallel the claims that the Progressives have made stick in order to distort the Framers’ initial plan. The next few letters in the Library of America’s compilation of the debate likewise are from the anti-Constitutional party. And they point out some of the things that they got very wrong.

One of Centinel’s worries was that the Constitution would create a permanent aristocracy. But his concerns center not on the executive, but on the Senate. Interestingly, Centinel’s analysis virtually places the Senate not in the legislative branch, but in the executive branch, since it has a role in approving treaties and confirming appointments. The Vice President, of course part of the executive branch, is President of the Senate. With a weak executive, Bryan is more concerned that we’ll see a hegemony of the Senate than of the Presidency. He’s correct that Montesquieu prescribed a strict separation of the executive and legislative powers as a precondition of liberty. But it’s the Presidency, with the help of a Congress that has delegated legislative power to the executive, and the complicity of favorable Supreme Court rulings, that has gotten there, not the Senate.

One of the recurring themes also was the preservation (or the alleged lack thereof) of the juries in civil cases. Now, eventually this was rectified in the 7th Amendment (thank you, George Mason), but what’s interesting here is the rhetoric. The anti-Constitutionalists assume that this was a deliberate act by the Convention, in order to help the higher courts usurp the lower courts, and to weaken liberties. In fact, this point was debated in the Convention, in the context of a Bill of Rights. But the reason that some opposed including it in the Constitution was that the laws varied from state to state, and that detailing which cases were appropriate for juries would be difficult. (There are some civil cases that traditionally did come before judges rather than juries; in such cases “equity” law was said to apply. I’m nowhere near an expert on what made a case an “equity” case as opposed to a jury case, and apparently the Conventioneers were similarly daunted by setting forth rules for the distinction.)

So, while Bryan and his cohort did get certain concerns correct, they missed others by a wide mark: it wasn’t the Senate that was the threat, and the fact that the Convention missed some elements didn’t imply a grand conspiracy to deprive people of their liberty.

UPDATE: After further reflection, the importance of juries in civil suits, which are by definition property rather than criminal cases, reinforces the fact that property rights were seen (and ought to be seen) as identical with political rights.

I’d also point out that Centinel’s concern that the federal courts would inevitably trump the state courts in civil cases has also not borne out. One instance is liability law, where the worse abuses have occurred in state courts (take asbestos, for instance), and the federal courts have been powerless to stop them. The situation has only gotten better with the revisions of state law to make them more sensible.

Ghosts of Constitutional Debates Past

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Constitution, General, History, PPC on December 23rd, 2010

I’ve been working my way (slowly) through the Library of America’s Debate on the Constitution, a two-volume set. While the Federalist is a – the – American political philosophy, it represents the thoughts of only three authors, and can’t possibly answer all of the concerns that people had about the Constitution at the time. The entire debate is a much more complete document, all the more valuable because it preserves the dissenting opinions. We do that in judicial cases because the reasoning itself may be important to future decisors. It puts the defenses in context, perhaps anticipates future arguments.

One of the first arguments against the Constitution comes in a letter from “Centinel” (they had plenty of variant spellings back then), one Samuel Bryan, in a letter to the Independent Gazetteer, dated October 5, 1787, less than a month after the Convention adjourned. While we consider the Constitution to be brilliant applied political philosophy designed to protect our God-given natural rights, the opponents were often concerned that it would prove to be a path to despotism, that is, that the Constitution itself contained the means to undermine liberty. Since the Independent Gazetteer didn’t survive long enough to sign a deal with Righthaven, I’ll quote at length.

He is skeptical of John Adams’s claim that a balance of powers at the federal level is even achievable:

This hypothesis supposes human wisdom competent to the task of instituting three co-equal orders in government, and a corresponding weight in the community to enable them respectively to exercise their several parts, and whose views and interests should be so distinct as to prevent a coalition of any two of them for the destruction of the third.

One could reasonably argue that the executive, with the collaboration of the Court and the capitulation of the Congress, has been progressively acquiring legislative powers.

Bryan anticipates the misreading of the Progressives of Article I Section 8:

“the Congress are to have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense, and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises, shall be uniform throughout the United States.” Now what can be more comprehensive than these words; … to grant… the absolute controul over the commerce of the United States….The Congress may construe every purpose for which the state legislatures now lay taxes, to be for the general welfare, and thereby seize upon every object of revenue.

He’s focusing on taxes, but the abuse of the general welfare clause is indisputable, and he anticipates the erasure of the proper reading of the Commerce Clause.

Bryan also predicts the hegemony of the courts, in particular, the hegemony of the federal courts over state courts, and of the erosion of state power at the hands of the federal government in general.

…it is more probable that the state judicatories would be wholly superceded; for in contests about jurisdiction, the federal court, as the most powerful, would every prevail.

To put the omnipotency of Congress over the state government and the judicatories out of all doubt, the 6th article ordains that, “this Constitution and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties made, or which shall be made under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land…”

By these section, the all-prevailing power of taxation, and such extensive legislative and judicial powers are vested in the general government, as must in their operation, necessarily absorb the state legislatures and judicatories, and that such was in the contemplation of the framers of it…

Now to be fair, in order to reach these conclusions, he has to ignore other sections of the Constitution, distort the Framers’ clear intent, and claim that later rebuttals are in bad faith. Congress is explicitly limited in the types of taxes it may levy. The Commerce Clause is not as expansive as he reads it. The General Welfare Clause is not blanket permission to enact any sort of law Congress wants to. Some of them would later be explicitly rectified by the Bill of Rights. Others would indeed be exploited by judges looking to change the system. But for him, these failings he claims to have discovered are a bug; for the Progressives, they’re a feature.

While we consider Madison, Hamilton, and Jay to be the heroes of the piece, that Centinel predicted so many of the distortions later introduced by the Progressives lends his arguments relevance.