Archive for category Business

Debt Markets React to Washington – Finally

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, PPC, President 2012 on July 29th, 2011

People have noted the failure to demand higher yields for treasuries, and concluded that the debt markets don’t believe there’s any problem with August 2, or 10, or any other date we care to mention. In fact, this was largely out of disbelief that Washington could fail to act.

In fact, this week, the debt markets have begun to react. Banks are beginning to pull money out of treasury-heavy money market funds, which in turn are selling treasuries and putting their money in banks. This has the effect of reducing the financial flexibility of each. The repo market – where financial institutions lend securities money to one another, using treasuries as collateral – is beginning to demand higher interest rates. Companies that don’t even like debt are issuing short-term commercial paper to make sure they have cash on hand. Let’s not turn this into panic – it’s not. But the markets are beginning to take prudent and overdue steps to protect themselves against a loss of liquidity in treasuries, even if it doesn’t mean technical default.

In the meantime, it appears that Speaker Boehner has agreed to a stricter Balanced Budget Amendment requirement for the 2nd round of cuts & debt limit increases – requiring passage rather than just a vote. I think this is a mistake.

There is every indication that Boehner Plan 2.0 was pretty close to the plan that he and Harry Reid presented to the President on Sunday, and which he indicated he would veto. But a close reading of the tea leaves also indicates that he was hoping that a strong enough statement against it would prevent him from actually having to make that decision. If he had signed it, it would have strengthened the conservative case for governance immensely.

Now, the House has probably made it more likely that they will end up voting on – and probably passing – some compromise between McConnell and Reid. That deal would, in fact, work towards marginalizing the Tea Party groups who have done so much to get us to this point.

I hope I’m wrong, and that the wording of the BBA is something that can get passed – it requires no presidential signature – and that the extra time we’re buying is put to good use making the case for it. Certainly Obama & the Democrats’ desire to run the federal budget on auto-pilot helps in that regard.

But if not, and if the 30 or so Republicans end up setting the stage for an exact repeat of this in 6 months, with no BBA in hand, they may well end up moving the debate to the left, rather than to the right.

One other point – I do think reasoned analyses such as McArdle’s, which show what will likely happen if we don’t raise the ceiling, without the histrionics, actually help our case down the road. If the markets do shudder a little bit, it should server as a spectre of what will actually happen, for real, when the debt markets finally decide to take that decision out of Washington’s hands altogether.

UPDATE: The Dollar-denominated Swiss Franc ETF, FXF, opened almost 2% higher this morning, and stayed there the whole day. I went back and looked, and since 2006, the daily percentage change has been bigger than this – in this direction – only 10 days, so this is definitely a multi-sigma event. One guess as to why it happened.

Obama’s Evergreen Goes Brown

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Business, Economics, Finance, National Politics, PPC on July 28th, 2011

Barack Obama and Harry Reid may not be able to produce a spending plan, but at least they have their old campaign talking points from 2008 to fall back on.

With the Senate having failed to produce a budget in over 2 years, the President’s budget having succeeded in uniting Washington to a degree not seen since it was under threat of attack 150 years ago, and neither willing to commit a spending plan to paper, they can be relied on to Blame Bush!

The White House has put out a graphic purporting to show that – surprise! – 8 years under President Bush added more to the national debt than 2 years under President Obama. (They play with the numbers, by assuming that the cut in marginal tax rates didn’t stimulate growth, for instance.) That President Bush wasn’t exactly a fiscal conservative like FDR isn’t a secret to anyone. In its day, what was seen as recklessness spawned Porkbusters, the Tea Party in embryo.

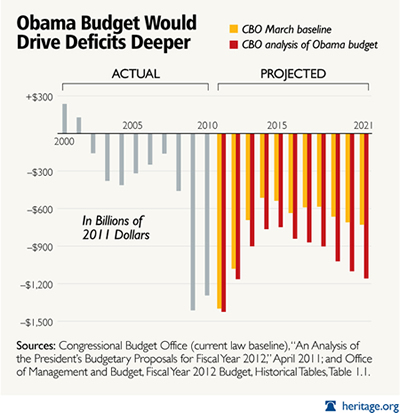

But let me remind you of this chart, originally in the Washington Post:

It’s been updated by the Heritage Foundation:

Much as Babe Ruth redefined baseball by showing what could be done when you try to hit home runs, so has Obama redefined deficit spending by showing what happens when you really put your heart and soul into it. You’ll notice, by the way, that the latter graph compares the CBO to itself, rather than to the White House budget, because, haha, there isn’t a White House budget.

Note also how the color bars in each graph look the same, only they’re shifted to the right by two years in the update. It’s evident that 2010 and 2011 haven’t worked out as planned. It’s no wonder that Tea Partiers don’t really believe in out-year cuts; the deficit reduction hasn’t occurred because Obama’s policies and those of Congressional Democrats have stifled economic growth, and because they’ve been happy to govern illegally, without a budget for two years, leaving federal spending essentially on auto-pilot.

The other argument you hear is that Paul Ryan’s budget made use of the same accounting trick that Harry Reid’s budget-avoidance bill does: counting savings from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars we won’t be fighting. But Ryan’s plan was an actual budget. There were always holes, but the difference between “will spend” and “would have spent” means a lot less when you’re drafting an actual plan, than the difference between “will spend” and “will take in.” Ryan applied that $1,000,000,000,000 to a headline.

Reid proposes to let the President spend it between now and Election Day 2012.

The Democrats won’t produce a budget because they can’t, only they don’t want you to know that until after the election. So much for them.

The Tea Party folks have a different complaint, namely that Boehner’s Plan doesn’t go far enough. I’d like to see more cuts, too. But the idea, as I recall, was to use the debt ceiling deadline as a means for forcing a debate, forcing changes to the spending that is current and planned. It was never realistic to run the entire federal government out of the House of Representatives.

To that extent, the plan has been wildly successful. It has exposed the Democrats as dangerously delusional about the state of our finances, whose only current idea is to soak you to ratify a massive increase in the scope of our economy directly controlled by the government. The Boehner Plan re-adjusts the baseline, keeps the debate on the front burner pretty much through the election, and does it without raising taxes. These are major victories, and they would not have been possible without the Tea Party. Period.

That said, this particular fight is one of many. Pushing too hard right now, bringing on a technical default, or, more likely, putting incredible discretionary power in the hands of a teenage president, won’t be Sherman marching through Georgia, it’ll be Napoleon marching to Moscow.

There is considerable frustration abroad that we can’t simply win this thing already. But politics isn’t about that. Regardless, we’ll have to keep watching, pushing, and prodding. There aren’t any final victories in politics, either over the other party or within your own. The best use of this battle is to pocket the gains, and use the process to help prepare the battlefield for the next fight.

Individuals Pay Corporate Taxes – Just Not Always The Consumer

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Finance, PPC, Taxes on July 26th, 2011

Right now, our corporate tax structure makes no sense. It not only plays favorites, it drives many of the unfavored abroad. We have the highest corporate tax rate in the world, and the code is so riddled with exceptions, subsidies, and loopholes, disguised as “incentives,” that, as Megan McArdle put it, large companies basically have branch offices of the IRS on site to negotiate their tax bills.

So it makes sense that we should lower the corporate tax rate in exchange for cleaning the thing up.

It makes sense for all sorts of reasons, but not for one reason you often hear mentioned: that corporations just pass the increase along to consumers. They don’t. At least not always, because they can’t.

Who pays the tax is known as, “tax incidence,” and it depends on who has the fewest options. Economics recognizes something called, “elasticity.” Supply Elasticity is how much the supply changes depending on the price, and if you’ve been following along, you’ll know that Demand Elasticity is how much demand changes in response to price changes. Vacation rentals have a pretty high demand elasticity. Gasoline, on the other hand, has a fairly low demand elasticity: the price goes up, but you still have to get to work.

On the supply side, airline seats have a fairly low supply elasticity; once an airline has planes in inventory, they’re not likely to mothball them, at least not in the short run. Tobacco, on the other hand, has a pretty high supply elasticity: when the price falls, supply falls quickly to match.

(A word for the pedantic: elasticity is not constant. At very high or low price levels, we as consumers or producers may behave differently. You can only drive so much, even at $1 a gallon, lowering demand elasticity. Of course, at that price, there won’t be any refineries operating, either. Also, there’s the economist’s eternal escape hatch – the long-run and the short-run. It may be expensive for me to increase or limit supply, but give me enough time, and I’ll find a way.)

So what does this have to do with the tax on eggs in China?

If I’m the one with fewer choices, I’ll probably have to eat most of the tax. Suppose, for example, I make the Indispensible Widget. It’s easy for me to ramp up and ramp down production, but it’s a commodity you have to have, every day, all the time. This gives me, as a producer, pricing power, and it means that when our taxes get raised, we can pretty much – up to a point – pass that expense along to you. (Remember, even monopolies don’t have infinite pricing power, and even commodities producers have competition.) So in that case, yes, it’s the consumer who gets shafted.

Now, suppose I sell something else, something where the industry can’t readily reduce supply, but you have a lot a choice in whether or not buy. High-end vacation hotel rooms, for instance. I may be able to reduce some operating costs, but those costs are what make them luxury. And vacations are very price-sensitive. There may be some times when I can just tack on the tax, but if I’m trying to compete with your staycation, I probably won’t. My shareholders and employees will eat it.

Note that there’s a similar relationship at work with how shareholders and employees split their end of the deal, too. Labor, too, has supply and demand price elasticity. If your labor is a commodity, you may not get that raise this year, or may even get a pay cut or fired. If you have specialized skills, ownership may not be able to pass the tax along to you, either.

The point here is that while individuals always pay corporate taxes, those individuals may be consumers, employees, or owners, depending on the business. It’s not as simple as businesses just passing the cost on to their customers.

Why is this an argument for tax reform? Hayek’s Pretense of Knowledge. The government can’t really know, except in the coarsest way, what the tax incidence for the corporate income tax will be on a given industry. Subsidies may end up going to industries that don’t need them, or that can’t find a good place to invest them. They may reward employees, or not; they may help subsidize demand, or not. And what was true yesterday may well not be true tomorrow.

Ideally, we would simply ditch the corporate income tax altogether. Salaries and employment would rise, as would consumption, dividends, and investment, so the government would see a lot of that revenue come back immediately, and much more from growth.

But barring that, a flat rate, which instead of aiming for universal “fairness” accepts the fact that industries and businesses differ from one another, is the wisest course.

The Kochs Visit Colorado

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Colorado Politics, President 2012 on June 26th, 2011

The Koch Brothers, owners of Koch Industries, have made a name for themselves over the years supporting libertarian and conservative causes. For being some of the few of such wealth to actively oppose the progressive agenda, they have earned themselves a level of venom pretty much unprecedented for private citizens.

Recently, as outlined over at Powerline, “filmmaker” Robert Greenwald has been producing a series of agitprop shorts designed to get out the left’s talking points about the vast conspiracy to undermine America as we know it, that the Kochs supposedly fund.

Today through Thursday, the Koch brothers will be holding a series of private meetings in Vail. Colorado’s Local Looney Left has decided to use it as a rallying point and fundraising tool (not necessarily in that order), and so has sent out an email soliciting for both. Naturally, it too, repeats most of the tropes that have been levelled at the Kochs:

Two of the biggest right-wing money men in America have organized a secret conference of top conservative donors, pundits, and elected officials this weekend near Vail. In January, more than 1,500 people protested a similar event held in Palm Springs, California–just before the Koch brothers, Charles and David Koch, launched their war on teachers and public employees in Wisconsin.

The Kochs’ association with Governor Scott Walker and his budget reforms exists almost entirely in the fevered minds of the Left. The Kochs’ contribution to Walker’s campaign comes to less that 0.1% of the total money raised.

The Koch brothers have provided millions of dollars to fund recent attempts to privatize Medicare and Social Security.

Privatize Medicare? Hardly. Maybe having established that the Kochs own Wisconsin, and the fact that Paul Ryan comes from Wisconsin…? Oh, hell, who knows. Ryan’s proposal doesn’t come close to turning Medicare in to a service voucher system, anyway. It would make most of Medicare look like Medicare Part B already does, but I don’t think anyone’s counting that as “private.”

As for Social Security, while a proposal for personal accounts would be most welcome, I don’t know of any serious legislation on the table to that effect, and there’s reason to doubt that the excellect idea of individual government accounts, no matter how personalized, are actually “private.” In the meantime, raising the retirement age and means-testing benefits are eminently bi-partisan ideas, and even the AARP has seen the handwriting on the wall on this one.

In the aftermath of the Citizens United decision, unprecedented amounts of corporate money is expected to be funneled into the political process next year.

The Kochs’ personal fortunes run into the billions. Koch Industries is privately held, but even if they were inclined to spent other investors’ money on politics, there’s no reason to think they need to. They’ve been doing so long before the Citizens United ruling, and the only way to stop them from doing so now would be to severely limit individual political speech – not that Democrats or the Left are above that.

Citizens United is mostly a boon to small- and medium-sized businessmen, who pay themselves last, but who find their ability to do business hamstrung by regulators and legislators. If lobbying is a legitimate business expense for them, why not political advertising? Especially as corporate money tends to split far more evenly than the union dues spent almost exclusively to support Democrats.

The irony of an astro-turfed group, seeded almost entirely by the money of four Colorado “progressive” billionaires complaining about the secretive influence of money in politics would be comical if anyone in the MSM actually bothered to call them on it from time to time.

While Vail seems to have been chosen for its picturesque setting rather than for Colorado’s possible centrality in the upcoming presidential election, perhaps the best hope is that we can get some of the local money off the sidelines and into the fight.

If they do, in fact, meet with the locals, they’ll probably be disappointed (if not already so) at the early, near-universal support for Mitt Romney by the party establilshment.

In the meantime, the Local Looney Left is planning a protest today through Tuesday outside the hotel (and probably inside, if they can manage it) to embarrass and disrupt a private meeting. It would be very interesting and revealing to see exactly how ill-informed those folks are with regard to their chosen bete-noir.

Greeks Bearing Grifts

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, Finance, PPC, Regulation on June 16th, 2011

And if the threat of starvation and a southern land rush weren’t enough here on Disaster Wednesday, there’s always Greece:

…But conditions in European markets are deteriorating. The main risk from Greece has always been contagion, and that process is already under way.

Most directly, prices of Portuguese and Irish bonds have fallen sharply, with 10-year yields rising above 11% and the cost of insuring their debt at record levels. The gap between Spanish and German 10-year bond yields is at its widest since January. The market is effectively giving no credit for any reforms or budget policies set out in the past six months.

The next link in the chain, the banking system, has been affected. In Spain, progress by banks on regaining market access has gone into reverse: Average borrowing from the European Central Bank jumped to €53 billion ($76.32 billion) in May from €42 billion in April.

Meanwhile, the contagion into core banks may be being underestimated by investors. Moody’s on Tuesday said it could downgrade France’s BNP Paribas, Société Générale and Crédit Agricole due to their holdings of Greek debt, and the ratings firm is looking at whether other banks could face similar risks.

Disturbingly, the worries have now reached non-financial companies, which have been virtually bulletproof this year. Investment-grade bond issuance has come to a near-standstill.

I seem to remember having seen this movie before, as the prequel to to 2008’s Episode IV: A New Hope. It may provide some cold comfort to Americans that this time, it’s taking place in Austrian, even if Germany’s pending LBO of the rest of Europe isn’t the Teutonic Shift the President had in mind a couple of weeks ago.

But there’s no particular reason to be complacent. Just as we’ve managed to convert our economy from fast-falling to encased-in-amber stasis, we could be in for another financial shock. Megan McArdle suggests one route: (I hate to quote a post in almost its entirety, but it’s short, and I don’t think I can say it better)

During the wave of banking regulation that followed the Great Depression, the government slapped heavy controls on the interest rates that banks could offer. They weren’t very good, which made the banks sounder, and consumers worse off. When inflation and interest rates rose in the late sixties, this became a big problem. Then some clever chap came up with the money market fund. Legally it worked like an investment fund, not a bank account: you invested in shares, with each share priced at a dollar. The fund invested in the commercial paper market and committed to keep each share worth exactly one dollar; whatever investment return they got was paid out as interest on your shares. This gave you something that looked a lot like a bank account, without all the legal tsuris.

In 2008, it turns out that these money market accounts were–as was always pretty obvious–a lot more like bank accounts than mutual fund shares. The Reserve Primary fund held a lot of Lehmann Brothers commercial paper, which plunged close to zero, meaning that there were no longer enough assets in the fund to make all the shares worth at least a dollar. This is known as “breaking the buck”, and it was not the first time it had happened. But it was the first time in more than a decade that it had happened at a fund which didn’t have enough money to top up the assets in the fund to bring them back to a value of $1. Bigger investment houses had been quietly topping up their money market funds for month, but Reserve Primary was a smaller firm, and they didn’t have the spare cash handy.This triggered a run on the money markets, which the government really only stopped by a) passing TARP and b) guaranteeing money market funds. But as Matt Yglesias points out, Dodd-Frank stripped Treasury of the authority to do such a thing again. And now the money markets are exposed to a Greek default.

Something like 45% of US Money Market funds have some direct exposure to Greek debt. Greece defaults, and many of these funds may be breaking the buck without Big Ben backstopping for them.

But that’s only the direct exposure. Then, there’s the indirect exposure, though insurance, and (probably) Credit Default Swaps:

Finally, it’s worth noting that once you account for the substantial payouts that US agents will have to make to European creditors in the case of a default by one of the PIGs, financial institutions in the US have roughly as much to lose from default as those in France and Germany. (See the figures in blue in the table above.) The apparent eagerness of US banks and insurance companies to sell default insurance to European creditors means that they will now have to substantially share in the pain inflicted by a PIG default.

The risk to US banks itself may be small, but the effects of having sold this insurance, and of people finding out that they sold this insurance, could be substantial:

The big US banks are well-capitalized now, and can fairly easily absorb losses of several billions of dollars in the event of a Greek default. But two serious concerns remain. First, I fear that this may have the potential consequence of exacerbating the flight to safety that will happen in the event of Greece’s default; if you have no idea who is really going to be on the hook and ultimately liable for CDS payments, your best strategy may be to trust no one. I don’t think that triggering post-traumatic flashbacks of the fall of 2008 is going to do good things to the market or the economy. Second, I wonder if there’s a public relations disaster just lying in wait for the big US banks. After all, how will you feel (assuming you don’t work on Wall Street) when you read the headline that Big Bank X lost money because it sold billions of dollars of credit default insurance while it was on taxpayer life-support? Rightly or wrongly, I’m guessing that Big Bank X will not be very popular for a while.

This also doesn’t address the US banks’ exposure to the European banks, the ones that may go under when Greece finally decides to call it quits. They may have positive exposure to those banks, and find that holdings in them, or loans to them, are suddenly less liquid than they had hoped.

There’s one other issue that I haven’t see addressed anywhere, and that’s the question of securitized Greek debt. Remember that we thought the subprime crisis could be “contained,” because subprime mortgages were such a small portion of the overall mortgage market, never mind the credit markets as a whole. Then it turned out that the subprime assets were poisoning entire classes of securities, since they were so highly leveraged. Is it possible – and this is purely speculation, I really do not know the answer to this – it is possible that people have done the same thing with sovereign debt, and that there are CDOs out there with Greek debt incorporated into them? Securities that could suddenly default, even though they only contain a small mix of drachmas in there?

Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff point out that after every financial crisis, governments find themselves with significantly higher debt, as they seek to stop the dominoes from falling. The potential exists for European governments to become dominoes themselves, and if McArdle is right, there’s some risk (probably small, but hard to say how much) that won’t even be able to step in again and keep our own house in order.

GE, We Bring Bad Ideas To Light

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Business, Economics, National Politics, PPC, Stimulus on June 15th, 2011

In a prior post, I mentioned that Obama’s favorite courtier CEO, Jeffrey Immelt, was part of a Jobs & Competitiveness Council, ostensibly tasked with finding ways to put Americans to work. It’s the kind of thing that government always says it’s doing, anyway. After all, we have a Commerce Department, a Labor Department, an Education Department, and dozens, if not hundreds, of bureaus, agencies, subalterns, and fiefdoms devoted exclusively to this problem.

From the bureaucracy’s point of view, they’ve spent decades of time, billions of taxpayer dollars, and millions in campaign contributions to get where they are, and they’re not going to let a hand-picked set of toadies show them up. The beauty of it is that either their success or their failure shows that our actual redundant population lives and works within 10 miles of the Capitol.

If by now anyone at all has any faith left in this kind of commission, it should be put to rest by its initial recommendations.

I Don’t Know. The Administration Has Seemed Pretty Shovel-Ready To Me From Day 1.

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Business, Economics, National Politics, PPC, Stimulus on June 14th, 2011

By now, you’ve probably seen this rueful admission by President Obama – evidently part of a longer comedy routine – that the stimulus didn’t actually do much the stimulate:

Over at Powerline, Scott Johnson takes Obama to task for laughing at unemployment, and imagines Obama & Immelt as the new Hope & Crosby, and suggests The Road to Tripoli as a working title for their first picture. I was thinking The Road to Serfdom or The Road to Ruin, myself.

In all seriousness, though, isn’t this just a president who realizes he has a real vulnerability, and is trying to laugh at it, at his own error? Is this reallly all that different from Bush pretending to search the Oval Office for the WMDs, the video for the White House Press Dinner that had the lefties in a snit a few years back?

Obama’s lousy at it, because he takes himself too seriously, and really can’t laugh at himself. I’ve never seen him do it, anyway. Bush had great comedic timing and a real sense of humility.

Of course, as an indictment of his competence, it’s far worse than Bush’s joke. Bush’s knowledge was limited to what his intelligence apparatus brought him, his perceptions were shared by the rest of the world. Many argued against going into Iraq, but virtually nobody thought Saddam wasn’t building or maintaining an arsenal of WMDs.

Obama not only got the macro wrong (Germany, for instance, has made different fiscal choices), but also, in the most generous interpretation of these comments, didn’t even bother to do due diligence about where the next couple of generations’ money was going when he spent it. A less generous interpretation – consistent with the Alinskyite acolyte – is that he knew perfectly well that it was going to bureaucrats, and now wants to be seen as fixing the problems that he himself created.

The press conference was the rollout of the first half of Obama’s so-called Jobs & Competitiveness Council, the “fast action” steps, in favored courtier co-chair Jeffrey Immelt’s words. But that’s for another post.

In For The Long Haul

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, PPC, Transportation on June 6th, 2011

Well, this is interesting. From Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s AAR reports from the last two years:

Coal, as you can see, makes up about half of car loadings, and that’s headed down. Just from the couple of years, it looks as though there may be some seasonality in Intermodal, falling off in the last quarter. I’ll know some more when I look at Union Pacific (back to 2002 and also mostly western) and CSX (back to 2006, but mostly the northeast and south). Intermodal has improved through this year, but coal has been dropping for about 6 months.

Since the beginning of the year, coal has decoupled – so to speak – from the rest of loadings, which have climbed slightly or stayed level, even as coal has dropped. We export a great deal of coal, and BNSF serves the western half of the country, Mexico, Canada, and the Gulf of Mexico. (The railyard north of downtown Denver is a BNSF railyard, although we have a fair number of UP lines through the state, too.) There have been reports that China’s been slowing down, and nobody really trusts – or should trust – the official numbers coming out of there. Is it possible that fewer coal loadings as a sign of slackening Chinese demand?

I’m not quite sure what to make of the stagnating carloads combined with the improving outlook for intermodal. We know that, over long distances, trains are more efficient than trucks. Intermodal will continue to grow as a percentage of both rail traffic and overall freight ton-miles. Is it possible that this is just more inefficiency being wrung out of the system? Any other ideas?

More Pension Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on May 29th, 2011

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that pensions are moving more money back into hedge funds:

Also, pension officials are using the historically strong returns of hedge funds to justify a rosier future outlook for their investment returns. By generating more gains from their investments, pension funds can avoid the politically unpalatable position of having to raise more money via higher taxes or bigger contributions from employees or reducing benefits for the current or future retirees.

The Fire & Police Pension Association of Colorado, which manages roughly $3.5 billion, now has 11% of its portfolio allocated to hedge funds after having no cash invested in these funds at the start of the year.

…

While pensions have been investing in private equity and what are called alternative investments for many years, hedge funds have represented a smaller part of their portfolio. The average hedge-fund allocation among public pensions has increased to 6.8% this year, from 6.5% for 2010 and 3.6% in 2007, according to data-tracker Preqin. (Emphasis added.)

PERA’s own investments in hedge funds are unclear from the latest data, but if the “Other of Other” category is representative, it could be about 10% of their holdings.

This may be good in the short run. There’s no doubt that some of these funds have done well, being able to hedge some of their risk away and focus on capturing industry or sector returns. But there are some serious dangers here, and they are complicated by the problems already noted with pension accounting.

First, there’s no such thing as risk-free alpha. Remember, the market tries to match risk with return. If someone is selling an investment with 10% return and the risk associated with equities, beware. Because if that were possible over the long run, enough people would pull money from equities and pile it into this mythical investment, so the returns would match. Either that, or there’s hidden risk in there that justifies the extra return.

Either way, in the long run, the funds are taking on more risk, or will have the additional return arbitraged away as more people invest in these strategies. Also, if many of the funds are using the same strategy, it may be difficult for them to execute trades that actually allow them to limit risk, as they may all be trying to sell overperformers, or buy hedges, at the same time.

Another threat to pension funds is in the bolded sentence above. Managers are not only using these returns to justify higher projected returns. What goes unstated is that they’ll also use them to justify the higher discount rates, that make their pensions look better-funded than they are. It’s a perfect example of the perverse accounting incentives built into fund management.

Last, these strategies are not necessarily transparent, making it difficult for independent auditors to even assess the risk that these pensions are taking on.

I’m all for finding ways to hedge away risk, and there’s no reason that pension funds can’t participate in some of those techniques. I’m skeptical that, in the absence of fixing the underlying problems, this approach is going to do any more than paper over problems, yet again.