Archive for category Taxes

The Eternal Tax Debate – Lessons from the 1920s

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Economics, History, Taxes on November 28th, 2017

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

Growth was too low, as the post-war economy struggled to recover from a recession.

The new president and his treasury secretary were convinced that a serious package of tax reform could unleash much-needed growth.

And they had a plan. The top marginal rate was too high; it should be in the 20s. The estate tax drove down the price of assets and should be eliminated. There were too many special carve-outs. Tax-free interest on municipal bonds was diverting capital from private enterprise.

To be sure, not all the proposals were for lowering tax rates. The secretary wanted a capital gains rate higher than the income tax rate.

But the political situation was working against them. Their own party was split, and they ran into opposition not just from the openly Progressive party, but from the Progressive wing of their own party, which included the Senate Majority Leader. Opponents of the administration’s plans pointed out that the bulk of the benefits would go to the wealthy, including the treasury secretary himself.

Opponents argued that federal revenue would plunge; the treasury secretary persuaded the president that unlocking capital would cause an economic boom and swell the tax take. They argued for a top tax rate around 40%.

Conservatives believed that nearly everyone should pay something. Progressives disagreed.

Scandals, distractions, and Congressional investigations also sapped the president’s attention and political capital.

The president and the treasury secretary also complained that the time it was taking to pass a bill was extending the experimentation of the previous Democratic administration, and the destructive uncertainty that accompanied it. Passing something, they argued, even if it didn’t meet their exact specifications, would be more important than dithering and passing nothing.

Eventually, the treasury secretary would get his tax reform package, mostly on his own terms, and he and the president would see federal revenue leap upward as a result. (He wouldn’t get everything; the secretary wanted a top marginal tax rate in the 20s; Congress seemed more inclined to something around 40%.)

The treasury secretary was Andrew Mellon, and it would take another round of elections, the death of President Harding and the accession of President Coolidge to make it happen.

Ironically, these tax reform plans weren’t originally even Mellon’s. Wilson Administration Treasury Department bureaucrats developed them after the war. They hoped to transform federal tax policy from an ad hoc patchwork into a permanent, systemic tax regime, the emphasis being on permanent.

Ninety years later, we are still having substantially the same discussions, on substantially the same terms. Does that mean that the Progressives were successful? Perhaps, and perhaps not.

Mellon dubbed his approach “scientific taxation,” designed to maximize revenue while minimizing the tax burden. But the fact that we’re still picking over many of the same details in 2017 suggests that the science is far from settled.

Analogies to past epochs in American history are not currently commonplace. Some see a darker replay of the late 60s and early 70s. Others, more alarmist, see a replay of the pre-Civil War 1850s divide. Those comparisons rely more on the social atmosphere than on specific issues.

It’s unusual to see a policy debate stagnating, with the same arguments, over roughly the same issues, for nearly a century.

To some degree, this is the peculiar result of its being both narrow and central. The income tax itself cuts across numerous persistent philosophical and political divides.

Superficially, the room for policy debate is narrow: after 100 years, the personal income tax’s basic structure – progressive rates with special-interest credits and deductions – remains essentially the same.

But the tax’s seeming simplicity masks endless room for mischief, and therein lie the complications.

The personal income tax contributes nearly half of the federal government’s annual revenue; combine it with the payroll tax, and just under 5/6 of federal tax revenue is based off of personal income.

Lowering or raising rates will affect not only an individual year’s deficit, but also the economy’s rate of growth and attendant opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, and employment. The overall take calls into question the size of government as a whole.

The amount of progressiveness, both the top rate and the number of people who pay nothing, raise the ill-defined but politically potent question of “fairness.”

In policy terms, each deduction or credit raises the question of whether or not the government should be supporting or suppressing the industry or choice involved. What gets exempted raises the question of privileged institutions like university endowments or state and municipal debt and taxes.

In fact, the whole structure implicitly accepts the idea that it’s the federal government’s job to support or suppress certain economic decisions. That credits and deductions can only be taken under certain circumstances open the door to micromanaging those decisions.

And every one of these credits and deductions immediately acquires a non-partisan, which is to say bipartisan, constituency, either because it helps someone or hurts their competition. Thus are we treated to the spectacle of otherwise conservative Republicans in New York, California, and New Jersey defending national taxpayer subsidies for their expansive state and local governments.

That goes a long way toward explaining why we’re stuck in the same debate.

And unfortunately, why we probably will be for a long time.

The Death of the Death Tax?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Taxes on April 15th, 2015

Thursday, the House will vote on HR1105, the Death Tax Repeal Act of 2015. This is one of the most unfair taxes on the books, taxing assets and cash that have already been taxed several times along the way. The bill has 135 co-sponsors, 134 of whom are Republican; kudos to Sanford Bishop of Georgia.

The Democrats would have you believe that the tax falls primarily on the exceedingly wealthy, and so is designed to prevent the concentration of multigenerational wealth. Perhaps the reason the tax has been such a dismal failure in preventing income inequality is that its premise is so flawed. The very wealthy have any number of strategies available to them to avoid paying the tax. Does anyone think Chelsea Clinton is going to go do productive work any time soon?

In the meantime, the tax absolutely crushes asset-rich/cash-poor businesses and farms, of the kind held by successful, but not opulent, families. Often, the choice is between selling assets (and usually it’s the bigger businesses that gobble these up), and taking a loan out. Rep. Kristi Noem (R-SD) appeard on Fox News to discuss the bill. Her family had to take out a 10-year loan to pay the death tax bill when her father was killed in an accident on the farm.

How long before Obama or Elizabeth Warren or Hillary!™ takes a page out of the student loan debacle and decries banks making unfair profits off of families’ misfortune, and demands that the government take over making those loans.

Devolving the Gas Tax

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Taxes, Transportation on December 12th, 2013

Over at Complete Colorado, the Independence Institute’s Dennis Polhill writes in support of a proposal to devolve the lion’s share of the federal gas taxing authority back to the states, and remove federal restrictions on the states:

The Transportation Empowerment Act, introduced by U.S. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, and Rep. Tom Graves, R-Ga., gradually would lower the federal gas tax from the current 18.4 cents to 3.7 cents per gallon over five years. The legislation also would lift federal restrictions on state departments of transportation.

…

Not only would devolving the federal gas tax to the states result in a major boon to Colorado roads and bridges, it also would honor a promise made to the American people more than 50 years ago. In 1956, Congress passed the National Defense Highway Act to construct the Interstate Highway system. The temporary federal gas tax was promised to expire when construction was completed.

For all practical purposes, interstate highway construction was finished in 1982. Unfortunately, taxes almost never go away, or get smaller. Nor do government agencies or programs. Coincidentally, 1982 marks the same year roads outside the interstate system became eligible for federal funding. By tripling eligible mileage, the U.S. Department of Transportation used road revenues to fund other things more aggressively. Increasing amounts of gas tax revenue were siphoned to fund non-road programs, and congressional earmarks mushroomed.

For Colorado voters, the salient point is that we’ve been shorted on the deal, sending five cents per gallon to Washington that we never see back. There was a time when federal development of large-scale road projects made sense, in order to avoid things like the Kansas Turnpike dead-ending in an Oklahoma field, because Oklahoma couldn’t get its act together:

But given that much of this money isn’t going to roads any more, anyway, putting an end to the Colorado-DC-Colorado round trip makes sense.

It’s certainly better than this monstrosity from Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) that would add 15 cents to the federal gas tax in order to make up for the money that they’re siphoning off to pet projects, a prospect he doesn’t want to admit to:

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A94bMb9gaD8[/youtube]

Transparency At A Steep Price

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Finance, Taxes on October 22nd, 2013

This post originally appeared on Watchdog Wire Colorado (“Gov. Hickenlooper Channels His Inner Pelosi“).

Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) famously said about Obamacare that, “We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what’s in it, away from the fog of the controversy.” That seems to be the line that Gov. John Hickenlooper (D) is taking with respect to PERA spending by the state’s school districts, and Amendment 66.

In a recent post that has garnered attention from both the Colorado Springs Gazette and the Denver Post, we discussed the governor’s approach to PERA spending by the districts, which is to increase transparency in order to drive public opinion:

Gov. Hickenlooper: Well, if you want to fix that, if that’s what’s happening, then we can’t legislate that. There’s a certain amount of money that goes into the districts, and that is the way our education system is structured. If you want to fix that, put it up on our website, how much of that money the district is spending on PERA. And I guarantee you the parents will go nuts.

In response to another question at that same October 8 event, Hickenlooper touted the transparency website as part of the “Grand Bargain” of Amendment 66, that the entrenched interests and monopoly power of the districts and the teachers unions would likely not have accepted the transparency without the additional money from Amendment 66’s tax increase:

And the other question of whether you could just do this – let’s assume the website was for free, to get that into the bill, the school districts, and the school administrators, would have fought it like crazy, because it’s going to make their life hell.

The only reason they were willing to let it be in this bill was because we had a tax increase.

It’s why they call it, “The Grand Bargain.” We’ve got all this stuff that no other state – I mean – doesn’t it sound like a great idea to have that transparency? And yet why is it that not a single other state has that kind of a website. (Emphasis Added.)

In short, he’s arguing that the only way to get the transparency is to vote for the tax increase first.

However, the legislature has in the past mandated transparency, and with no objection from the districts. In 2010, the legislature approved HB10-1036, the Public School Financial Transparency Act, virtually without objection. Among other things, it’s the reason that school districts have to post Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports and Quarterly Financial Statements online, along with check registers and credit and debit card purchase statements within 60 days of incurring the expense.

The bill passed without dissent through both Education Committees, and registered only one “No” vote on the floor of the House. It appears as though nobody testified against it in committee. Our own Ben DeGrow did testify in favor of it before the House Education Committee.

If the governor is now arguing that such an extension of the transparency requirements would meet with stiff resistance from the school boards and teachers unions, he’s essentially arguing that there’s not enough support within the majority Democratic caucus in the legislature to get such a bill passed, and admitting perhaps more than he would like about union influence within that caucus.

In order to garner support for the tax increase from reluctant parties, Gov. Hickenlooper has pledged to put SB10-191’s tenure reform on the ballot in the form of a Constitutional amendment, should the expected legal challenges succeed. If the tax increase amounts to the price to be paid for bringing his own caucus along on transparency, it calls into question his ability to fulfill that pledge once the tax increase has already passed.

Amendment 66 – Exacerbates The Revenue Problem

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Education, Taxes on October 13th, 2013

Rather than aid poorer school districts, Amendment 66 will, in the long run, likely end up hurting them, making budgeting harder for those districts, and lives more difficult for both the students and teachers who live and work there.

The state is complaining that it’s chronically short of cash for education, both as a result of decreased tax revenues since the recession, and the state’s budget restrictions. In response, they have proposed a two-tiered income tax system, the first in over a quarter of a century in Colorado.

Currently, Colorado has a flat, 4.63% income tax rate from the first dollar of income. The proposed system would raise that to 5% for income under $75,000 and to 5.9% for income over $75,000. Colorado has roughly 1.8 million filers in the first bracket, and just under 600,000 filers in the proposed upper bracket. Proponents claim this would raise roughly $1 billion a year in new revenue, which they also claim would go largely to the poorer and neediest school districts.

How could a $1 billion tax increase make things worse for these districts? Because the income tax, unlike the property tax, is pro-cyclical. When the economy is doing well, incomes are highers, and receipts from the income tax rise. The income tax varies much more with the business cycle than the property tax does because incomes vary much more than property values do.

This conclusion is borne out by a 2010 Tax Foundation study comparing variations in various sources of state and local income nationwide. Corporate income tax was the most volatile, with personal income tax next. A more recent analysis, also by the Tax Foundation, confirmed this result, and found that over the last 20 years, the least volatile source of state and local revenue has been the property tax, the primary source of income for school districts.

This has particular resonance for Colorado. In 2008-2009, Colorado ranked 36th in year-over-year percentage change in state tax revenues; increasing the state’s dependence on personal income taxes will likely make them more volatile, and adding a progressive component will make them more volatile still.

Under Amendment 66, the state will backfill much of the difference for poorer districts. This means that those poorer districts will find themselves more dependent on a more volatile source of income: personal income taxes. When times are good, this will help them. But when the next recession inevitably hits, it’s those poorer districts, the ones that Amendment 66 claims to help the most, who will in fact, suffer the most.

A New Challenge to Amendment 66

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Taxes on October 2nd, 2013

Late this afternoon, a lawsuit was filed challenging the validity of many of the signatures gathered by the supporters of Colorado Initiative 22, now Amendment 66, which seeks to raise state income tax and create a two-tiered tax system for the state.

The lawsuit was filed in Denver District Court by a bipartisan pair of former state legislators, Norma Anderson (R) and Bob Hagedorn (D), and has not yet been scheduled for hearing. According to the press release by Coloradans for Real Education Reform, its primary charge is that the IDs of many of the petition-gatherers were not properly validated by notaries.

If upheld, this challenge could invalidate as many as 39,000 of the nearly 90,000 signatures ruled valid by the Secretary of State’s office. (Initiative supporters had turned in just over 165,000 signatures, of which just under 76,000 were rejected as invalid.) The Initiative needs a little over 86,000 signatures to qualify, so this section alone would invalidate far more than enough to keep the measure off the ballot.

Colorado had long had what was regarded as one of the nation’s least restrictive ballot access requirements for both statewide initiatives and proposed constitutional amendments. A 2009 law, HB09-1326, passed with strong bipartisan majorities in both houses of the legislature, tightened up those requirements in a number of ways. It contained restrictions on signature-gatherers, including those that are being challenged in this section of the lawsuit.

Part of the 2009 law requires that circulators sign an affidavit on the petition sections they submit, stating that all of the signatures on that section were gathered in their presence, and that to the best of their knowledge, the signers’ information is correct.

The revised section, Colorado Revised Statutes 1-40-111, reads that:

(C) The circulator presents a form of identification, as such term is defined in section 1-1-104 (19.5). A notary public shall specify the form of identification presented to him or her on a blank line, which shall be part of the affidavit form.

(II) An affidavit that is notarized in violation of any provision of subparagraph (I) of this paragraph (b) shall be invalid

The plaintiffs argue that in many cases, the circulator himself wrote down the form of ID that was presented, rather than the notary, as is required by law. This would seem to defeat the purpose of having the notary verify the identification.

The 2009 law also inserted language stating that, “that he or she understands that failing to make himself or herself available to be deposed and to provide testimony in the event of a protest shall invalidate the petition section if it is challenged on the grounds of circulator fraud.” This would seem to mean that signatures gathered by any circulator whose affidavit is being challenged, and who won’t or can’t testify for this case would be thrown out, as well.

While a 2010 lawsuit (Johnson v. Beuscher) did challenge the validity of some signatures under the new law, this particular section was not used in that suit.

It would also seem that the filing of the suit by members of each party, neither of whom has a reputation for anti-tax activism, would lend it credibility. Part of the reason for the late date of the suit is the late date of the filing deadline; signatures were submitted in August, and the Secretary of State only issued his ruling on the petition on September 4.

More Bad News for Colorado’s Public Pensions

Posted by Joshua Sharf in PERA, Taxes on September 9th, 2013

Another month, another report showing the country’s pension problem to be worse than we thought, Colorado’s pension problem to be among the nation’s worst. This time, it’s a report from the non-partisan State Budget Solutions, “Promises Made, Promises Broken – The Betrayal of Pensioners and Taxpayers.”

In three significant measures, Colorado ranks in the bottom third of the nation’s public pensions: Its funded ratio is the 11th-lowest in the country, at 32.8%; the per capita unfunded liability is 15th-worst, at $16,158 per head; and as a percentage of the state’s GDP, Colorado is 16th-highest, at just over 31%. These dire rankings corroborate a recent Moody’s study that had Colorado’s unfunded pension liability in the bottom 10 as a percentage of state government revenues, another measure of the state’s ability to cover these debts.

They calculate the actual unfunded liability at just under $84 billion, nearly four times what PERA admits to, and $27 billion more than is estimated in an upcoming Independence Institute report. It should be noted, however, that the authors include five plans managed by the state’s Fire and Police Pension Association, much smaller plans which are not part of PERA.

The report takes issue with most public pensions’ investment return expectations, which usually vary between 7% and 9%, and the aggressive discounting oliabilities that most plans engage in. Instead of the optimistic – some would say wildly optimistic – return assumptions, the report’s authors use 3.225%, the 15-year Treasury rate. They also use that number to discount plans’ liabilities, arguing correctly that the discount rate should reflect a plan’s risk to its investors, not its returns on its investments. They argue that since these plans approach being risk-free investments, they should be discounted as such.

Personally, I think both the return assumption and the discount rate are too low. Even if 8% is unrealistic, and I’m not sure that it is, funds tend to have their money in diversified portfolios which will average returns higher than Treasuries. In addition, the plans are covered by state obligations, not federal ones. Investors have long recognized that state obligations carry more risk than do federal “risk-free” obligations, a fact reflected in the higher interest rates carried by state debt.

That said, the study makes two useful contributions to the debate. By making the return and discount assumptions it has, the report effectively sets an upper bound on the problem; surely no lower interest or discount rates could reasonably be chosen.

More concretely, by showing us to occupy the same neighborhood as such well-known pension basket cases as New Jersey and California, the report shows the foolishness of the approach of Amendment 66 – raising taxes, while appropriating all of the increased short-term revenue to ongoing operations.

COPs, Cash Flows, and Taxes

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Finance, PPC, Taxes on November 28th, 2012

We’ve pointed out some of the abuses of Certificates of Participation by the Denver and Jefferson County School Districts. However, there are times when COPs are good. One good use of COPs is as a cash management tool. Municipal bonds are usually non-taxable, which means their yields are lower than Treasuries of an equal term, especially in longer-terms, say, 10 years and over. Since a municipality doesn’t pay income tax, it can lend at the higher Treasury rate, while borrowing at the lower municipal rate, assuming that its credit rating is good. (I don’t care if Illinois has 30 years of gold stashed away, I’m not lending them a dollar for a hamburger to tide them over until next Tuesday.) The municipality can make a little reliable money on the arbitrage.

In essence, this is a tax-shift. The Treasury isn’t collecting income taxes that bond holders would normally pay, so that tax money is, in effect, shifted to the municipality. It’s the reason that Treasury yields are higher in the first place.

Over the last couple of years, though, this hasn’t really been possible. Municipal rates have stayed pretty steady, while long-term Treasuries have dropped precipitously as a result of all the various Quantitative Easings by the Fed. This has deprived municipalities of a source of cash. So while the stimulus was essentially a massive shift of debt from the states and municipalities to the Federal government, the feds are taking it back, inch by inch, by taking away this tax shift that had been available to the lower levels of government.

I don’t think it’s coincidence that one of the tax loopholes being mentioned for closure is the municipal bond interest. The feds would like to make this tax shift permanent by pushing up municipal yields above Treasuries. Most of the focus has been on the fact that this would make borrowing more difficult and expensive for municipalities. But it would also close off this tax shift as well. Both these facts will have the effect of making states and municipalities more dependent on federal funds.

Referendum Confusion

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Taxes on September 22nd, 2012

I’ve been posting recently on the proposed mill levy and debt increase for Jefferson County called 3A/3B. Denver Public Schools has similar measures on the ballot, also called 3A/3B. My post the other day about the accumulating debt burden on Denver School District voters was interpreted by some to be about the JeffCo measure.

That’s ok! The identical naming makes it easy. If you’re in Denver or Jefferson County, vote against 3A/3B!

Denver Schools Back For More

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Denver, Taxes on September 20th, 2012

Whenever the schools teachers unions come back for more, they always want you to forget how much they’ve taken in the past. This year, Denver Public School are proposing both a tax hike, and a debt issue. We’ll look at the tax hike another day. What many people don’t realize is that DPS has been borrowing like they had the Fed at the other end of the line (which they sort of did). Over the last 10 years, the bonded debt per capita has almost doubled, and the proposed $466 million increase would, I estimate, raise it almost another $700 per person.

That alone doesn’t tell us much, though, about our ability to pay this debt. The debt is funded through a mill levy on personal property, and is therefore limited based on the total assessed property value in the district.

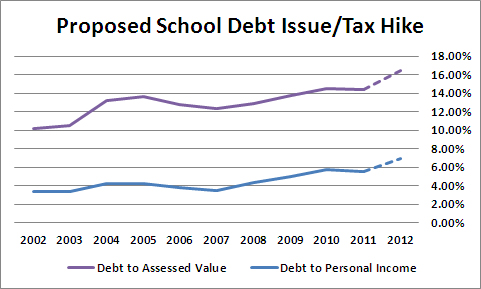

So to consider how affordable and wise additional debt is, we should look at the ratio of Debt/Assessed Value – in effect, how mortgaged is your property for this debt?

But unless someone annually rolls their property tax into their mortgage, though, they have to pay it out of current income or savings. Which means that it’s also important to consider the debt as a percentage of total personal income. The charts below show how those ratios have risen over the last ten years, with the dashed line estimating how the additional $466 million would increase these ratios:

Both ratios have risen, and would rise dramatically on passage of 3B. Note, though, that the burden on income is rising faster as a percentage basis (vs itself) than the burden on assessed value. The property tax is a regressive tax. While it’s nominally paid by the property owner, they really pass it on their renters, so the burden rests on the entire city. This chart shows that while the debt burden for the school district has been rising as a function of assessed value, it’s been rising even faster in terms of people’s ability to pay.

The DPS and the CEA will always argue that they need the marginal increase. What they won’t tell you is how these marginal increases add up over time.

Note on data sources: The Denver Public Schools, like all Colorado Public School districts, is required to file a Comprehensive Annual Finance Report. It gives the Net Debt for the school district, and also calculates the per capita, and the other ratios. But it only had that data through 2008. While the BEA calculates total personal income at the county level, its latest data was for 2010. The BLS publishes a total wages number at the county level, though, and had numbers through 2011. The ratio of the DPS’s reported total personal income for the county to the BEA number was 1.24, with a standard deviation of 0.02, so I decided to use the BEA numbers multiplied by 1.24 for 2002-2011. With current reports showing wages in Denver declining slightly, and employment static, I plugged in the 2011 number for 2012.

For the 2012 Assessed Valuation, I used the 2011 Assessed Valuation plus 10%, which is about what the Case-Schiller is showing for the Denver area.

For population, I used the official Census estimates for Denver, and then added 16,000 to the 2011 estimate for 2012. These differ somewhat from the population numbers used by DPS.

For the total debt, I simply added the $466 million requested to the latest 2011 Net Debt reported by DPS.