The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

The President entered office determined to pursue tax reform.

Growth was too low, as the post-war economy struggled to recover from a recession.

The new president and his treasury secretary were convinced that a serious package of tax reform could unleash much-needed growth.

And they had a plan. The top marginal rate was too high; it should be in the 20s. The estate tax drove down the price of assets and should be eliminated. There were too many special carve-outs. Tax-free interest on municipal bonds was diverting capital from private enterprise.

To be sure, not all the proposals were for lowering tax rates. The secretary wanted a capital gains rate higher than the income tax rate.

But the political situation was working against them. Their own party was split, and they ran into opposition not just from the openly Progressive party, but from the Progressive wing of their own party, which included the Senate Majority Leader. Opponents of the administration’s plans pointed out that the bulk of the benefits would go to the wealthy, including the treasury secretary himself.

Opponents argued that federal revenue would plunge; the treasury secretary persuaded the president that unlocking capital would cause an economic boom and swell the tax take. They argued for a top tax rate around 40%.

Conservatives believed that nearly everyone should pay something. Progressives disagreed.

Scandals, distractions, and Congressional investigations also sapped the president’s attention and political capital.

The president and the treasury secretary also complained that the time it was taking to pass a bill was extending the experimentation of the previous Democratic administration, and the destructive uncertainty that accompanied it. Passing something, they argued, even if it didn’t meet their exact specifications, would be more important than dithering and passing nothing.

Eventually, the treasury secretary would get his tax reform package, mostly on his own terms, and he and the president would see federal revenue leap upward as a result. (He wouldn’t get everything; the secretary wanted a top marginal tax rate in the 20s; Congress seemed more inclined to something around 40%.)

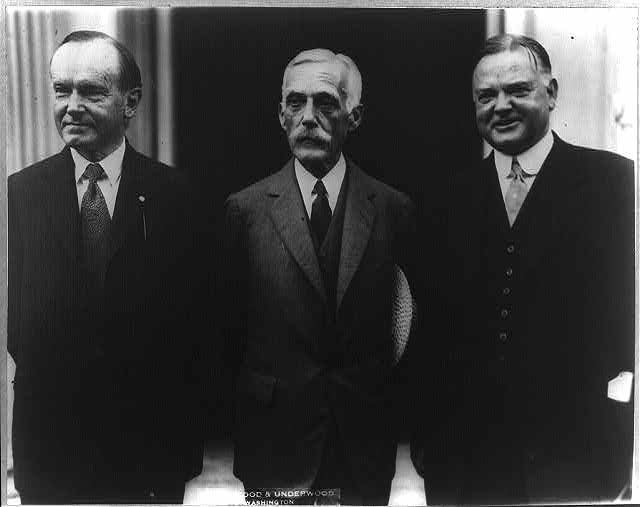

The treasury secretary was Andrew Mellon, and it would take another round of elections, the death of President Harding and the accession of President Coolidge to make it happen.

Ironically, these tax reform plans weren’t originally even Mellon’s. Wilson Administration Treasury Department bureaucrats developed them after the war. They hoped to transform federal tax policy from an ad hoc patchwork into a permanent, systemic tax regime, the emphasis being on permanent.

Ninety years later, we are still having substantially the same discussions, on substantially the same terms. Does that mean that the Progressives were successful? Perhaps, and perhaps not.

Mellon dubbed his approach “scientific taxation,” designed to maximize revenue while minimizing the tax burden. But the fact that we’re still picking over many of the same details in 2017 suggests that the science is far from settled.

Analogies to past epochs in American history are not currently commonplace. Some see a darker replay of the late 60s and early 70s. Others, more alarmist, see a replay of the pre-Civil War 1850s divide. Those comparisons rely more on the social atmosphere than on specific issues.

It’s unusual to see a policy debate stagnating, with the same arguments, over roughly the same issues, for nearly a century.

To some degree, this is the peculiar result of its being both narrow and central. The income tax itself cuts across numerous persistent philosophical and political divides.

Superficially, the room for policy debate is narrow: after 100 years, the personal income tax’s basic structure – progressive rates with special-interest credits and deductions – remains essentially the same.

But the tax’s seeming simplicity masks endless room for mischief, and therein lie the complications.

The personal income tax contributes nearly half of the federal government’s annual revenue; combine it with the payroll tax, and just under 5/6 of federal tax revenue is based off of personal income.

Lowering or raising rates will affect not only an individual year’s deficit, but also the economy’s rate of growth and attendant opportunities for investment, entrepreneurship, and employment. The overall take calls into question the size of government as a whole.

The amount of progressiveness, both the top rate and the number of people who pay nothing, raise the ill-defined but politically potent question of “fairness.”

In policy terms, each deduction or credit raises the question of whether or not the government should be supporting or suppressing the industry or choice involved. What gets exempted raises the question of privileged institutions like university endowments or state and municipal debt and taxes.

In fact, the whole structure implicitly accepts the idea that it’s the federal government’s job to support or suppress certain economic decisions. That credits and deductions can only be taken under certain circumstances open the door to micromanaging those decisions.

And every one of these credits and deductions immediately acquires a non-partisan, which is to say bipartisan, constituency, either because it helps someone or hurts their competition. Thus are we treated to the spectacle of otherwise conservative Republicans in New York, California, and New Jersey defending national taxpayer subsidies for their expansive state and local governments.

That goes a long way toward explaining why we’re stuck in the same debate.

And unfortunately, why we probably will be for a long time.