Archive for category Budget

PERA’s Resolute Optimism

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 7th, 2012

PERA’s Board recently voted to retain its wildly optimistic expected rate of return of 8% over the next 30 years. The decision has the effect of reducing the unfunded liability twice – once through higher returns, and again because they mistakenly use the rate of return as the discount rate. Remarkably, PERA’s board made that decision even as pension plans all over the country are reducing their expected rates of return.

The latest is the Orange County Employees Retirement System, which called a special meeting for Thursday evening to lower its expected return from 7.75% to 7.25%. It follows CalPERS, CalSTRS, and about 40 others of the 126 public plans in the National Association of State Retirement Administrators’ Public Fund Survey.

The most direct parallel is the change made only Tuesday by the Pennsylvania Municipal Retirement System, which lowered its expected rate of return from 6% to 5.5%, starting January 1. PMRS’s returns closely track those of PERA, returning an annualized 0.5% less per year over the last 10 years than PERA:

That comes to an annualized rate of 5.3% over the last decade for PMRS, or just below their new rate of 5.5%. PERA’s barely done better, and 5.8%, but insists on retain an industry standard, and wildly unrealistic, 8% expected rate of return.

Note that PERA’s average rate of return is 6.9%, while its cumulative average return is 5.8%. Of course, you can’t spend average returns, you can only spend cumulative returns. Yet another reason for PERA to be more, rather than less, conservative.

On the other hand, it must be encouraging to see PERA’s resolute optimism at a time when so many other plans are losing heart.

PERA, Personally

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 5th, 2012

One of the hardest things about discussing PERA’s liability is the sheer magnitude of the numbers involved. Twenty-five billion used to sound like a lot, until we started throwing around trillions. Forty billion, likely closer to the real number, sounds like it might be more, but it’s almost impossible to gauge how much more.

The chart below tries to show how PERA’s unfunded liability has grown in terms of our ability to pay it off. In 2000, PERA was nominally overfunded, meaning that all of its long-term liabilities were accounted for, and then some. In reality, this almost certainly wasn’t the case, but for the purposes of this post, we’ll just use PERA’s own current-dollar estimates of its unfunded liability.

Using BEA numbers for Colorado’s GDP, its total Personal Incomes, and its population, it’s a little easier to see the threatening direction this debt is taking. On a per-person basis, the unfunded liability now sits at just over $4000. That means that, to pay off the unfunded liability, it’s $4000 out of the earnings of the average Coloradoan. This includes those who are too old and too young to work, so for the average worker, the number is much higher. Four thousand dollars may not sound like a lot, but of course, it’s going to get worse – likely, much worse – before it starts to get better.

As a percentage of the state GDP and Personal Income, things are even more discouraging. PERA’s liability amounts to 8.15% of Colorado’s GDP, and nearly 10% of the total Personal Income. But this isn’t the only debt that the state, local, and district governments owe on your behalf, and it’s likely not the only debt you owe, either.

From 2004 to 2007, the ratios appeared to improve, but if you look closely, you’ll see that during a period of strong growth, the per-person dollar liability was flat, and the per-GDP and per-PI percentages barely moved. This strongly suggests that this is a liability that it’s going to be very hard to grow out of.

PERA will be quick to point out that you’re not going to be expected to cough up all of this money at once, and that they have a long-term, 30-year glide path to solvency. Any time any government program says it has a 30-year plan for solvency, you should stop listening and start moving your money someplace else. As we’ve noted before, PERA is significantly understating the size of the unfunded liability, both by overstating the rate of return and by misusing the discount rate. Moreover, mentally amortizing the liability over 30 years makes it that much easier to ignore until someone misses a payment, and the whole structure comes crashing down. I’m sure that San Bernadino and Stockton were using similarly comforting thoughts before they filed for Chapter 13.

Demagoguing PERA

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on December 3rd, 2012

Just in case anyone thought that the incoming Democrat majority in the Colorado legislature was planning to take a responsible approach to Colorado’s continuing PERA debacle – it has not yet reached the crisis stage – Speaker-to-be Mark Ferrandino has laid those fears to rest. Morningstar has published a report reiterating what anyone with any sense already knew, that PERA is not “fiscally sound,” with a funded ratio of 58%. PERA complains that that only accounts for the state division, and that including other divisions raises the fundedness to 60%. This is the equivalent of a terrible student trying to argue his grade up from an F- to an F.

Ferrandino, instead of understanding that promises are being made that simply cannot be kept, demagogues the issue, claiming that, “There are some who would like to use the economic downturn to take away people’s pensions.” I suppose it’s progress of a sort that he acknowledges that we’re still in an economic downturn, but where on God’s green earth does he think the money comes from to pay those pensions, if not from the retirement savings of the rest of the people in the state? Where is the fairness in using the force of law to place the pension of a 30-year-old government worker ahead of the average Coloradoan’s ability to provide for himself and his family?

Don’t expect much help from the Senate, either, where incoming Senate President John Morse has hired SEIU flack Kjersten Forseth to be his chief of staff.

As California collapses, Colorado has a golden opportunity to pick up businesses looking for more healthy homes. In 2010-11, the Denver metro area had the 7th-highest rate of in-migration from other parts of the country. Unfortunately, the state’s Democrats seem bound and determined to import not California’s prosperity, but its pauperizing policies instead.

Certificates of Prevarication – Part II

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Denver, PERA, PPC on November 27th, 2012

Yesterday, I wrote about the Jefferson County School District’s use of Certificates of Participation to get around the State Constitution’s requirement for a public vote before issuing general obligation debt. I had forgotten that once upon a time, Denver Public Schools did almost exactly the same thing.

The scheme – used widely around the state, and even by the state, is for the district to set up a corporation and then lease its own property back from the corporation, with the lease payments matching bond payment due on debt floated by the corporation in the public debt markets. The debt isn’t exactly unsecured – the school buildings themselves serve as collateral. But there’s no separate revenue stream dedicated to the lease payments, which come instead out of general fund revenue, the very definition of general obligation indebtedness that the constitution seeks to limit.

In 2008, Denver Schools issued$750 million worth of both fixed- and floating-rate COPs, in order to recapitalize its own pension program, which had a $400 million funding gap. This was necessary for PERA to agree to absorb the DPS retirement system. While the ins and outs of the deal are beyond the scope of this post, suffice it to say that by 2010 the deal had become a key element in the Democratic US Senate primary between Andrew Romanoff and Michael Bennet, who had been Denver Schools Superintendent at the time of the COPs.

Our concern here isn’t whether or the the deal was well-structured on its own terms. It may well have been, and has, at any rate, since been refinanced on terms more favorable to the District. The point here is that Denver Public Schools, in order to facilitate turning over the unfunded portion of its own pension plan to the rest of the state, issued what is general obligation debt in all but name in order to cover a shortfall. That debt, issued without public approval, now accounts for 37.6%, or 3/8, of the school district’s entire long-term debt.

In the meantime, the burden of DPS’s unfunded pension liability has been neatly shifted onto the rest of the state. DPS may be required to step in with additional payments if an actuarial analysis shows that, in 30 years, the plan will be less sound than the rest of PERA. As of the 2011 CAFR, the plan’s fundedness had fallen from 88% to 81%, still the least-unhealthy PERA division by far. And the process of renegotiating what is likely to be, as with most public pensions, an unsustainable burden on the taxpayers, got much more complex with the addition of the state and PERA as explicit parties to the contract.

Certificates of Prevarication

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA on November 26th, 2012

I’ve already written about the Jefferson County School Board’s decision to default on its Supplemental Pension Plan. It turns out it’s also using something called Certificates of Participation as a loophole to circumvent the State Constitution’s ban on governments issuing general obligation debt without a vote of the people. They’re not alone in this, and it can lead to a significant understatement of a government’s – thus the citizens’ – total indebtedness.

In 2006, the JeffCo School Board voted to offer teachers the option of taking a lump-sum payment for the value of their pension benefit, or to stay in the 10-year payout program. In order to help capitalize the buyout, the Board issued $38.7 million worth of Certificates of Participation (COPs), with maturity dates from 2007 to 2026.

Note that even if the Board succeeds in closing down the Supplemental Retirement Program and discharging itself of about $7.4 million of unfunded obligations, approximately $33.1 million worth of principle on those COPs will remain on the books.

Since the State Constitution prohibits governmental entities from issuing unsecured debt without a vote of the citizens, how is such a this possible?

Keep your eye on the shell with the pea.

Technically, the COPs weren’t issued by the School District, but by a corporation, the Jefferson County School Finance Corporation. Nine school building were leased by the District to the Corporation for some nominal amount, and then leased back to the District by the Corporation. The lease payments by the District to the Corporation are designed to match the bond payments due by the Corporation.

The bonds are therefore secured by the revenue stream provided to the Corporation by the lease payments from the District. What shows up on the financial statements of the District aren’t the COPs, but the lease payments, which are budgeted annually, not as a formal, long-term commitment.

Investors, of course, are not fooled by this. The entire term of the lease shows up on District’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) as a Capital Lease, as a long-term obligation (see Note 10, p. 66), not just the next year’s payment. They show up directly, as “Certificates of Participation” on the District’s Debt Capacity Schedule 9 (P. 114). If the payments are missed, it will damage the credit rating of the District.

To be fair, JeffCo is far from the only jurisdiction to use this mechanism to get around the ban on general obligation debt. Denver City Council used a similar mechanism to launder its own obligations that it incurred when it backed debt for the Union Station redevelopment project, in order to secure federal funding. This appears to be a legal means of side-stepping the constitutional limitation.

The State Constitution recognizes the danger inherent in debt, which is why bond issues need to be approved. If investors don’t treat the Corporation as a separate entity from the District in evaluating creditworthiness, why should the state?

Note:

Here is the relevant paragraph from the debt issuance, describing the shell game, and showing that it specifically contemplates the ban on general obligation debt and is designed to avoid it (emphasis in original):

Neither the Lease nor the Certificates constitutes a general obligation indebtedness or a multiple-fiscal year direct or indirect debt or other financial obligation whatsoever of the District within the meaning of any constitutional or statutory debt limitation. Neither the Lease, the Indenture nor the Certificate have directly or indirectly obligated the District to make any payments beyond those appropriated for any Fiscal Year in which the Lease shall be in effect. Except to the extent payable from the proceeds of the sale of the Certificates and income from the investment thereof, from Net Proceeds of certain insurance policies and condemnation awards, from Net Proceeds of the subleasing of or a liquidation of the Trustee’s interest in the Leased Property or from other amounts made available under the Indenture, the Certificates will be payable during the Lease Term solely from Base Rentals to be paid by the District under the Lease. All payment obligations of the District under the Lease, including, without limitation, the obligation of the District to pay Base Rentals, are from year to year only and do not constitute a mandatory payment obligation of the District in any Fiscal Year beyond a Fiscal Year in which the Lease shall be in effect. The Lease is subject to annual renewal at the option of the District and will be terminated upon occurrence of an Event of Nonappropriation or Event of Default. In such event, all payments from the District under the Lease will terminate, and the Certificates and the interest thereon will be payable from certain moneys, if any, held by the Trustee under the Indenture, any amounts paid under the policy of insurance, and any moneys available by action of the Trustee regarding the Leased Property. The Corporation has no obligation to make any payments on the Certificates.

Jefferson County Schools Propose Retirement Plan Default

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on November 25th, 2012

Welcome, Instapundit readers! While you’re here, take a look at posts on Certificates of Participation. Perhaps your state has something similar…

On Thursday, November 8, the Jefferson County School Board voted to ask teachers participating in its Supplemental Retirement Program to take a buyout for what would amount to about 64 cents on the dollar.

By following other public pension systems into what amounts to a default – albeit partial – JeffCo Public Schools join the parade of cautionary tales for those relying on the promises of public programs like PERA. As Glenn Reynolds of Instapundit is fond of reminding us, promises that cannot be kept, won’t.

History of the Plan

Quoting from a 2009 RFP for a plan financial advisor (emphasis added):

The Supplemental Retirement Plan was created in 1999 for employees who worked in full-time or job-share positions which were covered by an association. It was designed to replace a bonus-type program for retirees who met age and service requirements, with a tax-advantaged vehicle. Benefits are intended to supplement, not replace, PERA retirement benefits. Participation in the plan was immediately frozen upon its creation.

The District had originally committed to fund $90 million dollars toward a combination of pension plan benefits and sick and personal leave payouts at a rate of $9,000,000 per year for 10 years. However, budget cuts reduced the annual plan contributions and stretched out the plan’s original funding timetable. The plan has been underfunded since its creation. In 2007, the District purchased certificates of participation and deposited the funds into the plan for the purpose of meeting its stated funding obligations and has now exceeded its original funding commitment. Further contributions to the plan are not likely to be made. Subsequently, existing retirees and employees who met the full vesting requirements of 20 years of eligible service and age 55 were offered a one-time ability to have their benefits satisfied with a lump-sum payout at the plan’s stated discount rate. As a result, participant count, liabilities and assets have decreased in the plan and the overall funded status of the plan has improved. It is anticipated that at some point the plan will need to declare actuarial necessity and terminate or reduce plan benefits for non-vested participants. After the lump-sum payouts, the plan amended its investment policy to be more conservative, in an effort to protect the funding of benefits for existing retirees and vested participants.

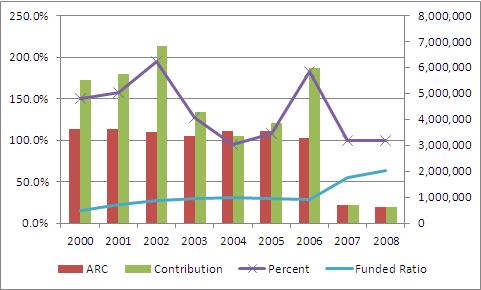

The plan wasn’t underfunded for lack of district contributions. According to the latest available plan financials, also from 2009, the district met or exceeded its annual contribution every year until 2009, with the exception of a slight shortfall in 2004. The combination of payouts and lower-than-necessary returns kept the plan funding under 32%, until the 2006 issuance of $37 million of Certificates of Participation (more about that in a coming post) reduced the outstanding obligations starting in 2007.

As of the 2009 report, the plan had $20.8 million in obligations, $7.4 million of which were unfunded.

Issues with Transparency

There appear to be a number of significant transparency issues with the way the plan has been handled.

The November 8 meeting itself raises issues of transparency and obligations of full disclosure to the public. The meeting discussion was held in a 45-minute executive session. Executive session is supposed to be reserved for legal advice, not for general discussion of motions before the Board. It is unthinkable that the Board received a 45-minute legal briefing, after which it proceeded directly to a vote.

Moreover, at least the topic of an executive session is required by law to be posted in advance of the meeting. Here’s the notice that was posted outside the Board’s meeting room the evening of November 8:

There is, evidently, case law to suggest that the recording of the Executive Session should therefore be made public, since the session – although not the vote – were conducted in violation of statute.

The most recent financials available online date from 2009, three years ago. Even in the absence of significant financial changes, plan financials from the most recent year should always be available.

Also note that the teachers were offered a buyout in 2006 – which the smart money, including current Superintendent Cindy Stevenson took – the 2009 statement RFP for a plan financial advisor all but admits that the plan will terminate and default on the remaining obligations at some point. Whether or not this likelihood was made clear to the teachers who chose to remain with the plan in 2006 is unclear. What it clear is that Stevenson, and possibly current Board member Jill Fellman, were made whole during the 2006 buyout offer, while other teachers were not.

UPDATE: According to the FY2011 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, in 2011, the Board decided to terminate benefits for anyone who hadn’t reached the thresholds of age 50, and 20 years of service as of the end of the 2011 plan year, 8/31/2011. “The plan is still operational for active and deferred vested participants and beneficiaries in receipt of payment.” It is those members who will be asked to take a cut in their benefits. The district has also “determined that additional contributions for the foreseeable future would not be made to the Plan.” (Note 16, P. 72)

The funded ratio has fallen to 50.6%, and the unfunded liability as of August 31, 2010 is $8.8 million.

Correction: No vote was actually taken at the November meeting. (I left early because of the descent into executive session.) It is likely that there will be a vote at the December or January meeting. Stay Tuned.

PERA Gains a New Client Group

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, Economics, PERA, PPC on October 19th, 2012

What makes it so hard to fight the growth of government is its ability to create client groups seemingly at will, with the money of the very people it’s seeking to co-opt. I see it myself all the time at the JCRC, where what had been private, service groups are reduced to begging for scraps and favors in front of legislative committees. At one time they thought it more expedient to do that than to make the case for the value of their work to the community they served and represented. Now they’re caught, and even when they’re not temperamentally inclined to go along with the leftist agenda, they often do because they can no longer imagine doing business without government support.

So it happens with PERA, too, which has announced the Colorado Mile High Fund, a fund geared towards investing in Colorado entrepreneurs who have partners, but are also having a hard time finding additional capital.

“We heard from businesses around the state during the development of the Colorado Blueprint that increased access to capital is critical to their success and that of our state’s economy,” said Gov. John Hickenlooper. “The creation of the Colorado Mile High Fund will improve that access to capital and we are pleased that Colorado PERA’s partnership will benefit and help grow companies here in Colorado.”

The risks to the taxpayers and the foolishness of this sort of government adventure are all around us, but it’s hard to tell if that’s a bug or a feature of this plan. I don’t think PERA’s out to deliberately lose money, but investing in high-risk start-ups may not be the best decision for a defined benefit retirement fund.

Even if this turns out to be one fund in the option and under-used 401(k) option, entrepreneurs and start-ups will now have a reason to support increased funding for a government-sponsored employee retirement plan, whose money much come from the pockets of the taxpayer. The most dynamic sector of the state’s economy will be effectively recruited on behalf of its most stifling.

How Does PERA Rate?

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Finance, PERA, PPC on August 15th, 2012

Not well. According to its latest Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, PERA has an unfunded liability of $25 billion, up from $15 billion last year, mostly because of a dismal rate of return in 2011, roughly 1.9%. Much of the criticism of public pensions has centered on their unrealistic expected rates of return, 8% in PERA’s case. This is certainly a cause of concern. While 8% is not unrealistic for equities historically, most people consider it to be wildly optimistic, certainly for the near future. And in any case, a constant rate of return doesn’t take into account the volatility of those returns.

But there’s a second rate, the discount rate, which PERA also has to estimate. It signifies something else altogether, and like the discount rate, PERA’s assumptions regarding the discount rate serve to make the fund look more solvent than it actually is.

What is a discount rate?

Another term for the discount rate is the “required rate of return,” not by the plan, but by the investors in the plan. In some sense, you can think of it as the Rate of Return in reverse.

The Rate of Return is used to estimate how much today’s investment will be worth tomorrow. PERA assumes an 8% rate of return, and for the moment, let’s humor them. This means that $1,000 today will be worth almost exactly $10,000 in 30 years.

The discount rate works in reverse. If I know that I’m going to need $10,000 in 30 years, then I can run that number in reverse, discounting by 8% each year, until I see that I need $1,000 in the bank today to be able to meet that obligation.

PERA, like most government pensions, uses the assumed Rate of Return as the Discount Rate. If you have $1,000 in the bank, after all, you have enough to cover a $10,000 obligation.

Why not?

Because in this case, the discount rate is supposed to discount back obligations, not assets. It is suppose to represent the required Rate of Return of the investors, in this case, the pensioners. And since the pensioners’ assets (their PERA benefit) is the same as PERA’s obligations, PERA should use the Rate of Return that pensioners should expect on their investment.

What rate is that? Basic economics says that risk needs to match return. The market should price assets with the same risk at the same Rate of Return. Otherwise, for two assets with the same risk, an investor could sell the one at the lower rate of return, and buy at the higher rate, and not have any risk at all. Obviously that’s not sustainable.

So the trick is to find an investment with roughly the same risk as PERA, and use its return as PERA’s discount rate. PERA is a contractual obligation by the state, much like a long-term bond. It can probably change the terms of PERA more easily than it could default on a long-term bond, but again, let’s assume that these are pretty close to having the same level of contractual obligation, and therefore, from the investors’ point of view, the same risk.

This is what private pensions have to do. A corporate pension would use, as its discount rate, a mix of high-quality corporate debt, because that’s market-traded debt at the same level of obligation as its pension obligation. It’s only by the grace of the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB), that PERA and other public pensions can get away with the higher discount rate.

Right now, according to MunicipalBonds.com, Colorado has long-term revenue bonds trading between 4,5% and 5%. Conveniently, if we use 4.75%, a $10,000 obligation translates to $2500 today.

So What Does This Mean?

Well, in our example, it shows how the level of fundedness is dependent on the choice of discount rate regardless of whether or not the 8% Rate of Return is realistic. If PERA has $1,000 in stocks, and chooses a discount rate of 8%, it looks as though it’s fully-funded. But if PERA is forced by accounting standards to choose the (more correct) discount rate of 4.75%, it’s underfunded by $1500, and is only 40% funded – even if we can realistically expect 8%.

That’s because the two rates really don’t have anything to do with each other. One is the rate of return PERA expects on its assets from its own investments. The other is the rate of return that pensioners expect on their investment. What PERA invests its money in is a policy decision. It may be good or bad policy, but pensioners expect to be paid, just the same as bondholders do, and that’s what determines the riskiness of the pension as an investment, not whether or not management puts it in gold bars or decides to go to Vegas and put it all on Red.

Ideally, PERA would match its return to its obligations. It would invest at something that also returned 4.75%, and have $2500 in the bank to be able to cover the $10,000 obligation, 30 years from now.

When it’s allowed to select a higher discount rate, though, it can get away with looking fully-funded with a much less money. Obviously, it has every incentive to do that. To do that, it has to seek investments with higher expected return. But in chasing higher returns, it’s also taking on additional risk.

Not only does the higher discount rate make PERA look more solvent than it is. It also encourages it to make riskier investments with its pensioner’s money.

Moody’s Sees Bloomberg’s “Laughable” And Raises…

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, PERA, PPC on July 13th, 2012

Being State Treasurer and trying to hold the Colorado Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA) to account can be a frustrating experience, as Walker Stapleton shared with Sean Hannity on Fox News Channel in June:

“I asked for some basic financial information about the defined benefit plan, where people were promised a rate of return, a massively inflated rate of return of 8%, Sean, that everybody from Warren Buffett to Michael Bloomberg have said is ridiculous and insane and preposterous. And they keep this rate of return promise, on purpose, to pervasively underfund the plan, and create a liability on the backs of our kids and their kids, and future generations of Americans.”

Now, it’s not just Mayor Bloomberg, it’s Moody’s.

Moody’s Investors Service has asked for comment on a proposed adjustment to its valuation of the public pension liability in the United States. One of those changes would lower both the discount rate and the expected rate of return to a standard of 5.5%.

This would have the effect of tripling the estimated unfunded liability, from $766 billion to $2.2 trillion.

Trillion.

With a T.

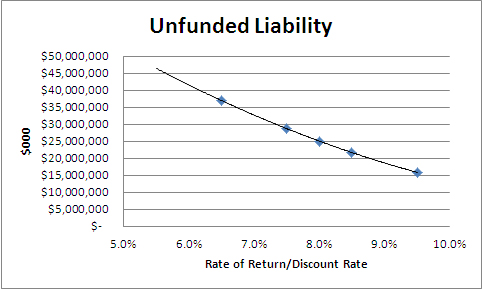

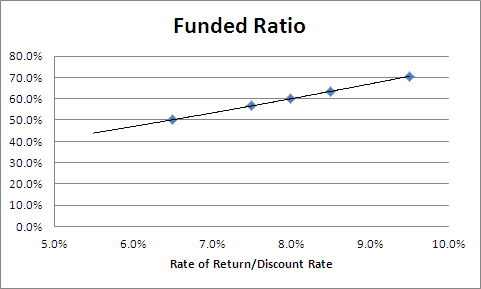

PERA has more than 97,000 current benefit recipients receiving an average monthly benefit of nearly $3,000. It runs a sensitivity analysis on its liability, varying the rate of return and the discount rate from 9.5% (no adjectives need apply) to a merely overstated 6.5%. At 6.5%, it is barely 50% funded, and Colorado’s unfunded liability is just a shade under $37 billion.

A reasonable estimation back to 5.5% puts the unfunded liability at $45 billion, and the funded rate near death-spiral territory at 43.8%. I’m sure that when PERA releases its 2012 annual financial report in about a year, they’ll have done those calculations themselves. Here’s the recently released 2011 version.

Stapleton, a PERA board member, sued last year to get access to PERA records. That effort was rebuffed in Denver District Court in April.

“This is a battle for transparency that is going on all across our country,” Stapleton said on Hannity’s show. “It’s critical that we win this battle, because it’s critical for state budgets going forward.”

Amortize This!

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Education, Finance, PERA, PPC on July 6th, 2012

In Pension accounting, the amortization period is how long it would take to pay off the current unfunded liability, based on current contributions, and current employees.

Typically, pensions try to keep that time at about 30 years, or a normal, long career. That does a pretty good job of matching contributions to liabilities.

The amortization period for PERA’s school fund is now 59 years.

PERA’s retirement age is 58.

Retirees who haven’t even been born yet are having their benefits amortized by current contributions.

Sleep well.