Archive for category Economics

Greeks Bearing Grifts

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, Finance, PPC, Regulation on June 16th, 2011

And if the threat of starvation and a southern land rush weren’t enough here on Disaster Wednesday, there’s always Greece:

…But conditions in European markets are deteriorating. The main risk from Greece has always been contagion, and that process is already under way.

Most directly, prices of Portuguese and Irish bonds have fallen sharply, with 10-year yields rising above 11% and the cost of insuring their debt at record levels. The gap between Spanish and German 10-year bond yields is at its widest since January. The market is effectively giving no credit for any reforms or budget policies set out in the past six months.

The next link in the chain, the banking system, has been affected. In Spain, progress by banks on regaining market access has gone into reverse: Average borrowing from the European Central Bank jumped to €53 billion ($76.32 billion) in May from €42 billion in April.

Meanwhile, the contagion into core banks may be being underestimated by investors. Moody’s on Tuesday said it could downgrade France’s BNP Paribas, Société Générale and Crédit Agricole due to their holdings of Greek debt, and the ratings firm is looking at whether other banks could face similar risks.

Disturbingly, the worries have now reached non-financial companies, which have been virtually bulletproof this year. Investment-grade bond issuance has come to a near-standstill.

I seem to remember having seen this movie before, as the prequel to to 2008’s Episode IV: A New Hope. It may provide some cold comfort to Americans that this time, it’s taking place in Austrian, even if Germany’s pending LBO of the rest of Europe isn’t the Teutonic Shift the President had in mind a couple of weeks ago.

But there’s no particular reason to be complacent. Just as we’ve managed to convert our economy from fast-falling to encased-in-amber stasis, we could be in for another financial shock. Megan McArdle suggests one route: (I hate to quote a post in almost its entirety, but it’s short, and I don’t think I can say it better)

During the wave of banking regulation that followed the Great Depression, the government slapped heavy controls on the interest rates that banks could offer. They weren’t very good, which made the banks sounder, and consumers worse off. When inflation and interest rates rose in the late sixties, this became a big problem. Then some clever chap came up with the money market fund. Legally it worked like an investment fund, not a bank account: you invested in shares, with each share priced at a dollar. The fund invested in the commercial paper market and committed to keep each share worth exactly one dollar; whatever investment return they got was paid out as interest on your shares. This gave you something that looked a lot like a bank account, without all the legal tsuris.

In 2008, it turns out that these money market accounts were–as was always pretty obvious–a lot more like bank accounts than mutual fund shares. The Reserve Primary fund held a lot of Lehmann Brothers commercial paper, which plunged close to zero, meaning that there were no longer enough assets in the fund to make all the shares worth at least a dollar. This is known as “breaking the buck”, and it was not the first time it had happened. But it was the first time in more than a decade that it had happened at a fund which didn’t have enough money to top up the assets in the fund to bring them back to a value of $1. Bigger investment houses had been quietly topping up their money market funds for month, but Reserve Primary was a smaller firm, and they didn’t have the spare cash handy.This triggered a run on the money markets, which the government really only stopped by a) passing TARP and b) guaranteeing money market funds. But as Matt Yglesias points out, Dodd-Frank stripped Treasury of the authority to do such a thing again. And now the money markets are exposed to a Greek default.

Something like 45% of US Money Market funds have some direct exposure to Greek debt. Greece defaults, and many of these funds may be breaking the buck without Big Ben backstopping for them.

But that’s only the direct exposure. Then, there’s the indirect exposure, though insurance, and (probably) Credit Default Swaps:

Finally, it’s worth noting that once you account for the substantial payouts that US agents will have to make to European creditors in the case of a default by one of the PIGs, financial institutions in the US have roughly as much to lose from default as those in France and Germany. (See the figures in blue in the table above.) The apparent eagerness of US banks and insurance companies to sell default insurance to European creditors means that they will now have to substantially share in the pain inflicted by a PIG default.

The risk to US banks itself may be small, but the effects of having sold this insurance, and of people finding out that they sold this insurance, could be substantial:

The big US banks are well-capitalized now, and can fairly easily absorb losses of several billions of dollars in the event of a Greek default. But two serious concerns remain. First, I fear that this may have the potential consequence of exacerbating the flight to safety that will happen in the event of Greece’s default; if you have no idea who is really going to be on the hook and ultimately liable for CDS payments, your best strategy may be to trust no one. I don’t think that triggering post-traumatic flashbacks of the fall of 2008 is going to do good things to the market or the economy. Second, I wonder if there’s a public relations disaster just lying in wait for the big US banks. After all, how will you feel (assuming you don’t work on Wall Street) when you read the headline that Big Bank X lost money because it sold billions of dollars of credit default insurance while it was on taxpayer life-support? Rightly or wrongly, I’m guessing that Big Bank X will not be very popular for a while.

This also doesn’t address the US banks’ exposure to the European banks, the ones that may go under when Greece finally decides to call it quits. They may have positive exposure to those banks, and find that holdings in them, or loans to them, are suddenly less liquid than they had hoped.

There’s one other issue that I haven’t see addressed anywhere, and that’s the question of securitized Greek debt. Remember that we thought the subprime crisis could be “contained,” because subprime mortgages were such a small portion of the overall mortgage market, never mind the credit markets as a whole. Then it turned out that the subprime assets were poisoning entire classes of securities, since they were so highly leveraged. Is it possible – and this is purely speculation, I really do not know the answer to this – it is possible that people have done the same thing with sovereign debt, and that there are CDOs out there with Greek debt incorporated into them? Securities that could suddenly default, even though they only contain a small mix of drachmas in there?

Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff point out that after every financial crisis, governments find themselves with significantly higher debt, as they seek to stop the dominoes from falling. The potential exists for European governments to become dominoes themselves, and if McArdle is right, there’s some risk (probably small, but hard to say how much) that won’t even be able to step in again and keep our own house in order.

GE, We Bring Bad Ideas To Light

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Business, Economics, National Politics, PPC, Stimulus on June 15th, 2011

In a prior post, I mentioned that Obama’s favorite courtier CEO, Jeffrey Immelt, was part of a Jobs & Competitiveness Council, ostensibly tasked with finding ways to put Americans to work. It’s the kind of thing that government always says it’s doing, anyway. After all, we have a Commerce Department, a Labor Department, an Education Department, and dozens, if not hundreds, of bureaus, agencies, subalterns, and fiefdoms devoted exclusively to this problem.

From the bureaucracy’s point of view, they’ve spent decades of time, billions of taxpayer dollars, and millions in campaign contributions to get where they are, and they’re not going to let a hand-picked set of toadies show them up. The beauty of it is that either their success or their failure shows that our actual redundant population lives and works within 10 miles of the Capitol.

If by now anyone at all has any faith left in this kind of commission, it should be put to rest by its initial recommendations.

I Don’t Know. The Administration Has Seemed Pretty Shovel-Ready To Me From Day 1.

Posted by Joshua Sharf in 2012 Presidential Race, Business, Economics, National Politics, PPC, Stimulus on June 14th, 2011

By now, you’ve probably seen this rueful admission by President Obama – evidently part of a longer comedy routine – that the stimulus didn’t actually do much the stimulate:

Over at Powerline, Scott Johnson takes Obama to task for laughing at unemployment, and imagines Obama & Immelt as the new Hope & Crosby, and suggests The Road to Tripoli as a working title for their first picture. I was thinking The Road to Serfdom or The Road to Ruin, myself.

In all seriousness, though, isn’t this just a president who realizes he has a real vulnerability, and is trying to laugh at it, at his own error? Is this reallly all that different from Bush pretending to search the Oval Office for the WMDs, the video for the White House Press Dinner that had the lefties in a snit a few years back?

Obama’s lousy at it, because he takes himself too seriously, and really can’t laugh at himself. I’ve never seen him do it, anyway. Bush had great comedic timing and a real sense of humility.

Of course, as an indictment of his competence, it’s far worse than Bush’s joke. Bush’s knowledge was limited to what his intelligence apparatus brought him, his perceptions were shared by the rest of the world. Many argued against going into Iraq, but virtually nobody thought Saddam wasn’t building or maintaining an arsenal of WMDs.

Obama not only got the macro wrong (Germany, for instance, has made different fiscal choices), but also, in the most generous interpretation of these comments, didn’t even bother to do due diligence about where the next couple of generations’ money was going when he spent it. A less generous interpretation – consistent with the Alinskyite acolyte – is that he knew perfectly well that it was going to bureaucrats, and now wants to be seen as fixing the problems that he himself created.

The press conference was the rollout of the first half of Obama’s so-called Jobs & Competitiveness Council, the “fast action” steps, in favored courtier co-chair Jeffrey Immelt’s words. But that’s for another post.

Contempt of Constituents

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, PPC on May 30th, 2011

Looking at the events of the last couple of weeks, it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that certain public officials in Colorado hold their constituents in contempt for the sin of not handing over their pocketbooks.

Legislative Democrats, with the cooperation of too many Republicans, have gone along with efforts to water down the state’s initiative process. And now, for refusing to go along with these plans, the people having spoken, must be punished.

In 2008, they turned down Referendum O, which would have allowed opponents of ballot measures to focus their efforts on any one Congressional district. And they turned down Amendment 59, which would have lined the teachers unions’ pension plans by gutting TABOR.

This session, the Democrats failed to pass out of the Senate SCR-001, which would have created a hybrid Constitutional amendment-recision process that was clearly too complex for its stated goals.

Now, they have resorted to suing their own constituents in federal court, claiming that the Colorado Constitution is unconstitutional. The legal precedent here is clear. The courts have long held that the US Constitutional requirement for a “republican form of government” is non-justiciable, meaning that it’s a matter for the legislature and the people to decide. The most recent case, in 1912, upheld a state’s citizen initiative process against the very claim they seek to revive.

Remember, for “progressives,” it’s always Three Minutes to Wilson.

This effort is really a matter of politics, not of litigation, and that the plaintiffs are seeking a platform at taxpayers’ expense to make their case against TABOR.

(Let’s be clear: this is a Democrat initiative, and shame to the few officeholding Republicans who’ve given them cover to call it “bipartisan.” The big names are representatives of the “former” variety, and of the total list of 12, only 6 hold elected office, at the school board or city council level, most of which are nominally non-partisan.)

We’ve also heard that back in 2009-2010, the Colorado Springs City Manager at the time, Penny Culbreth-Graft, had instructed the city’s PR office to intentionally undermine its image, in the national media if need be, to browbeat the citizenry into voting for higher taxes. I’m sure the folks tasked with luring tourists, students, and businesses to the area were thrilled with this.

So think about this: in the last two weeks, we’ve seen public officials sue their citizens, and undermine the name of their own city. Why on earth should these people be trusted with more of our money?

More Pension Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on May 29th, 2011

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that pensions are moving more money back into hedge funds:

Also, pension officials are using the historically strong returns of hedge funds to justify a rosier future outlook for their investment returns. By generating more gains from their investments, pension funds can avoid the politically unpalatable position of having to raise more money via higher taxes or bigger contributions from employees or reducing benefits for the current or future retirees.

The Fire & Police Pension Association of Colorado, which manages roughly $3.5 billion, now has 11% of its portfolio allocated to hedge funds after having no cash invested in these funds at the start of the year.

…

While pensions have been investing in private equity and what are called alternative investments for many years, hedge funds have represented a smaller part of their portfolio. The average hedge-fund allocation among public pensions has increased to 6.8% this year, from 6.5% for 2010 and 3.6% in 2007, according to data-tracker Preqin. (Emphasis added.)

PERA’s own investments in hedge funds are unclear from the latest data, but if the “Other of Other” category is representative, it could be about 10% of their holdings.

This may be good in the short run. There’s no doubt that some of these funds have done well, being able to hedge some of their risk away and focus on capturing industry or sector returns. But there are some serious dangers here, and they are complicated by the problems already noted with pension accounting.

First, there’s no such thing as risk-free alpha. Remember, the market tries to match risk with return. If someone is selling an investment with 10% return and the risk associated with equities, beware. Because if that were possible over the long run, enough people would pull money from equities and pile it into this mythical investment, so the returns would match. Either that, or there’s hidden risk in there that justifies the extra return.

Either way, in the long run, the funds are taking on more risk, or will have the additional return arbitraged away as more people invest in these strategies. Also, if many of the funds are using the same strategy, it may be difficult for them to execute trades that actually allow them to limit risk, as they may all be trying to sell overperformers, or buy hedges, at the same time.

Another threat to pension funds is in the bolded sentence above. Managers are not only using these returns to justify higher projected returns. What goes unstated is that they’ll also use them to justify the higher discount rates, that make their pensions look better-funded than they are. It’s a perfect example of the perverse accounting incentives built into fund management.

Last, these strategies are not necessarily transparent, making it difficult for independent auditors to even assess the risk that these pensions are taking on.

I’m all for finding ways to hedge away risk, and there’s no reason that pension funds can’t participate in some of those techniques. I’m skeptical that, in the absence of fixing the underlying problems, this approach is going to do any more than paper over problems, yet again.

A Tale of Two Trains

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on May 18th, 2011

Funny thing about trains. They work well for people over short distances when the densities are high enough, but are terrible over long, wide-open spaces. They work well for freight over long distances, but lose those efficiencies over short distances.

In the first instance, Amtrak, with record ridership, is losing more money than ever. The northeast corridor is making money, but the long-haul trains through the sparsely populated Not Northeast gives it all back, and more. Amtrak’s argument for keeping routes like the California Zephyr is that they provide a service to people who have no other means of transportation. It’s exactly the same argument that led the ICC to require the Western Pacific to keep running this line even though they were hemmorhaging money.

How many people? Well, let’s take the segment that I often use, the part between Denver and Omaha. Now, people in Lincoln can drive to the Omaha airport. If we add up all the alightings and boardings between Lincoln and Denver for 2010, not including Lincoln and Denver, we get 13,295 people. That’s 13,295 people boarding and leaving the train at those four stations, for the whole year. About 36 people a day. Part of this is the time of night, but why do you think this part of the trip is overnight?

I love taking the train rather than flying. I like that it’s overnight, that it’s less hurried, that I can get up a little early or stay up a little late and work, and that I don’t have to subject myself to a cavity exam. But let’s not pretend this is an economical way to travel out here.

Freight is another matter. Ever since the ICC went away, rail freight as a percentage of total freight has been rising. In part, that’s because the lines have been able to invest a little in their operations, rather than being told that any profit is too much and being treated like utilities. And in the last year, intermodal traffic – a combination of rail and truck – grew 9% year-over-year, even as total rail traffic increased only 0.5%.

Steven Hayward has an interesting post about rail efficiency, and the fuel efficiency of engines:

In fact, the energy intensity of locomotives has improved substantially, with BTUs per freight mile falling by 65 percent since 1960. In other words, although total freight-rail miles have tripled since 1960, total railroad fuel consumption has remained about flat. If railroad locomotives had made no efficiency improvements since 1960, we’d have needed 9.2 billion gallons of fuel in 2009 instead of the 3.1 billion gallons actually consumed.

Passenger trains may have cafe cars, but freight trains have no CAFE standards of which I am aware.

Everybody Likes A Good Discount

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on April 24th, 2011

So with all the discussion about PERA, one key aspect of pension accounting hasn’t yet been mentioned: the discount rate. Now before you go all accounting-comatose on me, understand how important this is. Because with all the talk of how underfunded PERA is, it’s actually even more underfunded than you think.

Basically, if you have an obligation to meet, the discount rate is the rate you use to see how much money you need to have now in order to meet that obligation. So if you’re going to have to make good on a $100,000 obligation 10 years from now, and you use a 4.5% discount rate, you need to have about $65,000 now. If you use an 8% discount rate, you only need about $46,000.

Of course, the discount rate isn’t arbitrary. It represents a concept. The discount rate is the required rate of return, the return that an investor in that project requires, given the level of risk that he’s taking on.

The problem here, and how this relates to PERA (and many, many other public pensions), is that PERA is using the wrong discount rate. Instead of using the 4.5% discount rate, they’re using the 8% discount rate, which makes them look even less underfunded than they are.

Atlas Shrugged and the Railroads

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC, Transportation on April 22nd, 2011

Interestingly, one of the complaints that conservatives have about Atlas Shrugged is that the movie centers around a railroad. (McClatchy, too, but then, they’ll believe – or not – pretty much anything.) For some reason, they have a hard time believing that people will, or do, actually use railroads.

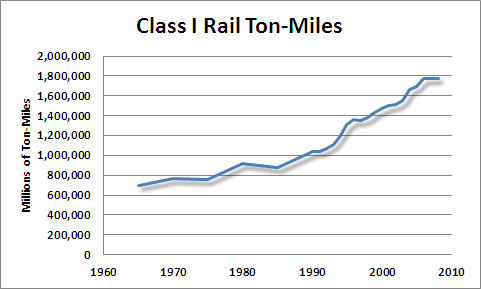

In fact, rail is increasingly important for freight, and has been on the upswing for a couple of decades now. Take a look at these following charts derived from Bureau of Transportation Statistics data. Overall Class I (major trunk line) ton-mileage stalled in the 70s, but started upward again with deregulation and the welcome death of the Interstate Commerce Commission:

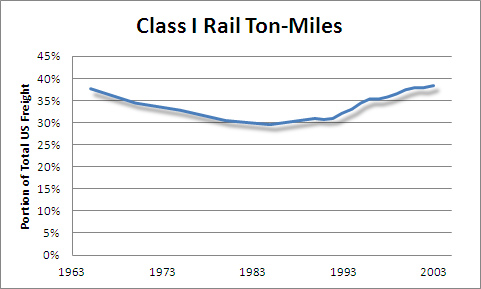

And as a percentage of total US freight ton-miles, it’s been headed up since the mid-80s:

About a year and a half ago, the Federal Railroad Administration published a report indicating that over long distances, rail is between 2-5.5x more efficient than trucking (Hat Tip: Future Pundit). I work at a trucking company, and I can tell you that intermodal – combined truck-train for long-haul shipments – is growing by leaps and bounds. Given the massive investment necessary to lay new track and secure new rolling stock, trucks continue to be a better choice for short-haul. But the best coast-to-coast operational choice seems to be rounding up the freight onto a container by truck, getting it to the railhead, and letting the train do the long-haul work. Trucks can then do the local or regional delivery at the other end. I even heard on long-time trucker complaining about this trend in the company cafeteria a few weeks ago.

I can’t remember where I saw it, but someone also poke fun at the idea of transporting oil by train. Hadn’t these people ever heard of pipelines? Aside from the apparent permitting nightmare in getting new pipelines approved, I can also tell you that the idea isn’t necessarily as ridiculous as it sounds. When were were looking at a couple of different ethanol plays at the brokerage, the need for specialized railcars was one of the drivers we took into consideration.

I initially also had thought that maybe it would have been better to focus on some newer technology rather than trains, but having seen the film, I’ve no doubt they made the right choice. Trains are visible, tangible, and connect with something very American.

The interesting thing about O’Rourke’s suggestion – that maybe they would have been better off setting the film in the 1950s – is that instead of liberating the filmmakers, it would have firmly trapped the film in past, reducing its relevance even more. Because almost everything Rand projected about trains actually happened. Unable to compete with subsidized roads, regulated to death by the ICC, trains deferred more and more maintenance, until northeast corridor rail freight virtually collapsed in the late 60s, leading to an actual government takeover and the creation of Conrail and Amtrak.

Once railroads were able to set their own rates again, they consolidated and recovered. Conrail’s operations have since been privatized, and the graphs above show the results. Union Pacific has been profitable right through the recession.

Railroads, as mentioned, do have a problem with the large capital investment necessary to expand, making them less flexible compared to trucks, just as light rail or commuter rail is less flexible compared to buses. But the idea that the country neither needs nor uses railroads just isn’t true, and fuel costs – as indicated in the film – will just make them more relevant for long-haul trips.

Solar Assumptions

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, PPC on April 20th, 2011

Some of my favorite listening is to Stanford’s Entrepreneur’s Corner. It seems to be guest lecturers to one of Stanford B-school classes, and they’re almost always entrepreneurs who’ve made good, coming back to share their wisdom. (The lectures tend to be entertaining, in Guy Kawasaki’s case, highly so.)

One of the recent lectures is by a fellow named Bill Gross, who’s founded a large number of companies, but is best known for eSolar and and Idealab. How he created Idealab, and turned it into a machine for generating ideas and exploring the interesting ones, while generating profit and not causing people to fear losing their jobs, is fascinating in itself. It bespeaks a willingness to think outside the normal managerial box, and a love of play, which is often missing in business. I think I’d like working for Bill Gross.

Unfortunately, he then turns to his other project, eSolar. Now, Gross doesn’t mention looking for government subsidies, although I haven’t researched how many of the solar farms he’s created benefit from them. But he freely admits that right now, on a per-unit-of-power-generated basis, solar cannot compete with oil. His thesis is, of course, that growing third-world economies are going to need power, too, and that there just isn’t enough oil or gas to power them through the next century.

Gross claims that solar is perfectly suited to the task, because unlike fossil fuels and wind, it’s evenly (democratically, in his word) distributed. And then he asks the really cool question: how can we apply a law we know: Moore’s Law, the progressive advance in computing power, to solar? He’s developed a means of closely coordinating the mirrors in a large solar-concentrator array, using microprocessors that help the mirrors tightly track the sun throughout the day, something that would have been prohibitively expensive only a few years ago. It’s very clever, really. Using these assumptions, he makes a compelling case for the long-term competitiveness of solar vs. fossil-fuels, without assuming huge runups in the cost of gas.

But I think his assumptions are flawed. First, solar power is decidedly not uniformly distributed. Colorado has 300 days or so of sunlight. Germany and Japan, solar leaders by virtue of massive (and since revoked) government subsidy, have far less sunlight. It’s not just climate, either. The farther you are away from the equator, the less sunlight you have on average, because the sun’s rays come in at a shallower angle during half the year. Even during summer, I wouldn’t want to rely on solar in Alaska.

He also puts his thumb on the scale in a more subtle way. Other energy sources can also inventively use computing power, both in their production and their consumption. By denying them the benefits of Moore’s Law, he’s giving his idea an advantage it won’t enjoy in the real world.

He argues that wind has its place, but it’s not a very large place. He argues that nuclear can’t provide enough power, and here, I have to say, I find his numbers unconvincing. (He maintains that long lead times and the expenses involved in making nuclear safe limit the number of plants you can create. But demand will make supply profitable, and you can finish as many as you can start.) So while he’s willing to live with a suite of energy sources, he really believes in solar.

Unfortunately, I think he’s built too many assumptions into that belief.