Photo Credit: Denver Infill Blog

This article was originally posted on Complete Colorado a couple of weeks ago. Since then, HB21-1117 has been introduced, which would fulfill the Colorado Municipal League’s dreams of letting cities and counties require rent control on portions of new construction, whether on new sites or on redevelopment of old sites. Of course, this will do nothing to make the bulk of Denver’s housing or regional housing more affordable. It will allow a few dozen lucky lottery winners to force up everyone else’s rent. That bill is scheduled for a hearing on March 10 in the House Transportation and Local Government Committee.

If you thought housing was getting even less affordable in Denver, it’s not your imagination.

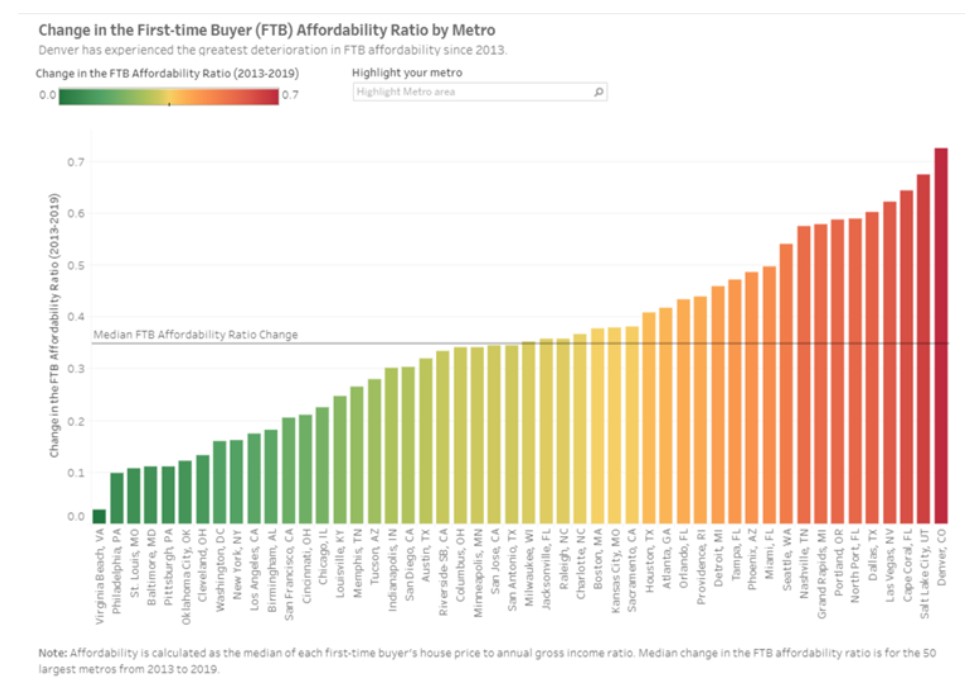

Denver’s affordability for first-time buyers (FTBs) was already among the worst in the country in 2013. By 2019, it had gotten worse faster than any other major metro in the United States, and now stands at #44 out of the top 50, nestled between the current city council’s role models of Seattle and Portland. This according to a 2019 study, Best and Worst Metro Area to Be a First-Time Homebuyer, from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

AEI developed a simple measure for FTB affordability: compare the selling price to the income.

To measure FTB affordability in a year, we first compute the price-to-income ratio for FTB transactions from 2013 to 2019, representing a total of over 3.2 million transactions. We then compute the median for each year and metro. The resulting affordability ratio thus accounts for the relative ease or difficultly for a FTB to afford a home given their income. The lower the ratio, the more affordable a metro is for FTBs; the higher the ratio, the more unaffordable a metro is for them.

In 2013, Denver had an affordability ratio of 3.5; by 2019, that had risen to 4.2, the fastest growth in the country, and good enough to drop the city from 38th in the nation to 44th. On a price-per-square foot basis, Denver dropped from 40th to 43rd, and this for some of the smallest homes surveyed for first-time buyers, 1361 sq. ft. in 2019.

Understand that this is a national trend; affordability decreased in all 50 metros surveyed. But in Denver, things got worse the fastest:

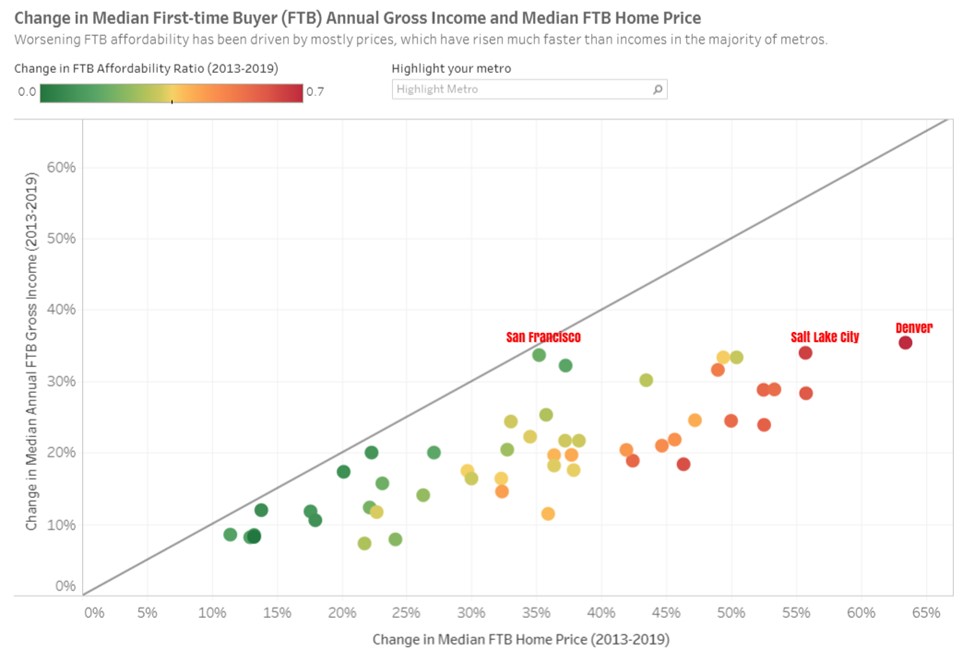

The math problem here isn’t hard to solve. Denver’s median income rose a little over 5% per year from 2013-2019, from $65,000 to about $88,000. That change was on a par with San Francisco, Riverside, California, Seattle, Sacramento, and Salt Lake City. But the median FTB home price rocketed up 8.5% per year, from $233,000 to $380,000. That’s 0.8% faster per year than Salt Lake City or Las Vegas:

To understand what this means for blue-collar workers, AEI developed something they call the Carpenter Index: what percentage of entry-level homes are less than 3x the average income of a carpenter, a proxy for a skilled blue-collar worker. Denver is the least-affordable metro in the west, and 94th out of the 100 largest metros, at 15%. Only 15% of Denver’s starter homes are available to blue-collar workers, using traditional mortgage affordability.

This follows a national trend. In 2012, despite being ranked 90th out of 100 metros, more than half of the metro area’s starter homes were affordable to an average blue-collar households.

Denver is to some extent a victim of its own success, as it remains a popular destination for those fleeing California’s urban dumpster fires or those simply looking for someplace nicer to move. But it’s also a victim of its own policy choices.

A new Wharton Index of land use regulatory restrictiveness published in late 2019 had the Denver metro area as the 14th-most restrictive in the country. Through the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG), it also works to compress development into existing corridors. This policy – known as an Urban Growth Boundary – reduces the land available for new housing, and drives up the price of even entry-level housing.

Urban growth boundaries also greatly limit the construction of new single-family housing, by taking the land necessary for such housing off the market, or by artificially increasing its price. This creates a more stagnant, stratified housing market. People in small homes can’t afford to move to larger houses, creating a traffic jam all the way back to smaller houses and apartments. Building more hi-rises, condos, and apartments may accommodate the influx, but it does nothing to satisfy people’s longstanding ambitions for some space of their own.