Among many conservatives, Civil War is in the air. For many, there’s a sense that things as they are now cannot go on. The civil order as we have known it is broken, and that things will end either in organized violence or in a semi-violent divorce.

Conservatives should remember not to immanentize the eschaton.

Instead of looking to the decades leading up to 1861, we have a far closer parallel with another decade – the 1790s.

Read this, from a 1961 number of American Quarterly, “Republican Thought and the Political Violence of the 1790s,” by John R. Howe, Jr.:

By the middle of the decade, American political life had reached the point where no genuine debate, no real dialogue was possible for there no longer existed the toleration of differences which debate requires. Instead there had developed an emotional and psychological climate in which stereotypes stood in the place of reality. In the eyes of Jeffersonians, Federalists became monarchists or aristocrats bent upon destroying America’s republican experiment. And Jeffersonians became in Federalist minds social levelers and anarchists, proponents of mob rule. As Joseph Charles has observed, men believed that the primary danger during these years arose not from foreign invaders but from within, from “former comrades-in-arms or fellow legislators.” Over the entire decade there hung an ominous sense of crisis, of continuing emergency, of life lived at a turning point when fateful decisions were being made and enemies were poised to do the ultimate evil….

In sum, American political life during much of the 1790s was gross and distorted, characterized by heated exaggeration and haunted by conspiratorial fantasy. Events were viewed in apocalyptic terms with the very survival of republican liberty riding in the balance.

Sound familiar?

Gordon S. Wood, in his magisterial Empire of Liberty notes that friendships were broken, there was political violence on a local scale scattered throughout the country. Everyday life and even religious affiliation became increasingly politicized. While this happened at the beginning of parties, those parties were largely organized around the personalities of their respective leaders, Hamilton and Jefferson.

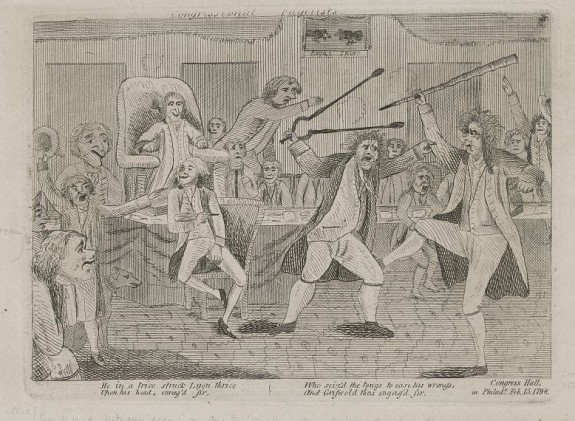

Jefferson’s Republicans didn’t necessarily expect to win in 1796, but the loss was clearly disappointing. In response, they adopted tactics that can only be described as resistance. They retreated to the state governments as bulwarks against what they saw as a too-powerful central government. They openly talked about states nullifying federal laws they considered unconstitutional. That picture accompanying this post? That’s from a fistfight on the floor of the US House of Representatives.

The Federalists, whose real leader wasn’t President Adams (who saw himself above parties), but Alexander Hamilton, continued to govern as though the government were simply the government, and any organized opposition to it was akin to treason. They reached out not to allies, but to the local or state elites to fill appointed posts and run for office. Instead of organizing, they wrote opinion pieces for the newspapers, and letters to each other.

Ultimately, it was organizing that brought the Republicans to power nationally. Aaron Burr’s efforts in New York tipped that state’s legislature, and thus its electoral votes, to the Republicans, and put Jefferson over the top. The Republicans would win the next six consecutive presidential elections, even as the part fragmented into regional and ideological factions of its own.

The Federalists were down, but not really out until the elections of 1816 and 1820. The conflict between the parties was resolved when the Federalists, by then almost exclusively concentrated in New England, ended up on the wrong side of the War of 1812. They worked to break the embargo and trade with Britain. They rediscovered their small-f federalist principles when their state militias frequently refused to cross the border into Canada. Old line churches often actually prayed for British victory.

By the end of the war, the country had a renewed sense of nationhood, and had turned away from Britain in the east, and towards its own future in the west. In 1789, almost all Americans had once been British subjects; by 1815, only those over 40 had, and even fewer could remember that time.

Neither the ideologies nor the tactics nor the self-identification with an “aristocracy” cut as cleanly today as they did in 1796. That’s less important than the fact that the conflict was eventually resolved, peacefully among Americans, even if it did require a war. Right now, the question of which issue will be the ultimate dividing line, which party is more in touch with the body politic, which one will emerge to create a durable, long-term majority, is still very much up in the air.