|

|

Main

May 27, 2009

That 10-Year Spot

A couple of things. First, we've been in a declining long-term interest rate environment for a long time. This is a huge plus for the economy is a number of ways, large and small. Second, that time is probably over. It doesn't necessarily mean we're headed for a period like the mid-50s to the mid-70s, but there just isn't much room for rate to decline, even if they wanted to.

Third, rates are still at historic lows, and we've seen quick increases even during the last 20 years when the trend was down, so there's not necessarily reason to panic just yet.

Fourth, the middle part of that graph should remind us all just how quickly things can get out of control.

About Those Interest Rates

The Chinese, the major purchasers of our debt, have been getting increasingly antsy about the possibility that we might monetize our debt, or start playing Weimar Germany to their France & England. Those nerves have been blamed for the recently rising spot yield for 30-year Treasuries, and the increasing doubt attending to recent Treasury auctions. There may be another possibility. The Chinese have been funding this debt in part because they hope that a stimulated and recovering American economy will help drag their export-driven economy out of its own slump. However, their own Keynesian stimulus has been subject to the same sort of inefficiencies and failures that have been predicted for ours here: The report "has some substantial findings," said Xianfang Ren, an

analyst with IHS Global Insight. She said the issues it raised --

funding delays and not enough stimulus for small- and medium-size

enterprises -- are big problems that have long been suspected. The

report also raised the matter of speculative bill financing, which

occurs when borrowers use loans not for working capital but to buy

stocks or speculate in other assets.

China has begun issuing rules to try to prevent this, but Fitch has begun sounding warnings about Chinese banks' balance sheets: In a report on China's banks published Thursday, Fitch said it is

seeing warning signals from the Chinese banking system. Chinese lenders

have been downgrading more "special mention" loans, those that are

considered about to default, to nonperforming status, marking them as

bad debt, said Charlene Chu, a senior director at Fitch Ratings China

and an author of the report. Chinese banks also have been increasing provisions for losses on

unimpaired loans, indicating that "the banks themselves see greater

losses down the line in loans that are currently performing," Ms. Chu

said. The report added to earlier warnings from the credit rater that lending quality in China is weakening.

This, even as HSBC and Citigroup scale back their lending in China. Could it be that China is now worried that it might need to shore up its own banks' balance sheets, and is holding back money for that purpose?

May 25, 2009

Channels of Information

Markets are only efficient when there's a free flow of information. One of the channels of that information are the sell-side analysts. I was one for a little over a year, and I can tell you that small-to-medium sized companies, even ones with significant coverage, were almost always happy to hear from us. We were their means of getting their stories out to the market at large. While we were always honest, and always discussed the company's warts, we also wouldn't have been covering them if we didn't think they were a good investment. Now, with the financial industry in flux, adn Wall Street hurting, there are fewer analysts around to cover stocks, and information flow may be suffering: Lost coverage can be meaningful not just to smaller companies but to

their investors. Analysts link corporate management with both

institutional and, to a lesser degree, retail investors. Though they

are faulted at times for being too cozy with companies and too bullish

on their stocks, analysts build a mosaic of information and analysis

that can help drive interest in a particular company. The good ones do

an even better job of understanding when corporate operations are

struggling and thus warn investors away. ...

Scholastic

Inc., a publisher of children's books including the U.S. editions of

the Harry Potter series, has lost coverage from Goldman Sachs, J.P.

Morgan and Citigroup, among others, leaving only three analysts still

tracking the company. One result: company executives now spend more

time on the road, meeting with potential institutional investors, since

Scholastic has fewer Wall Street analysts to pitch their story. "It has changed how we communicate with investors," says Jeffrey

Mathews, Scholastic's vice president of corporate strategy and investor

relations. "We spend much more time with institutional investors than

we did five years ago." Goldman said the Scholastic analyst left the

firm and coverage was dropped. Citigroup declined to say why it stopped

following the company and J.P. Morgan declined to comment.

Directly targeting institutional investors would tend to reduce the information available to smaller investors, and narrow the decision-making base. Information flow is slower, and fewer people are making informed decisions; both these effects tend to degrade market efficiency. This effect may be reversible, but another will be harder to undo. In the past, analysts could content themselves with analyzing market forces, the actions of thousands or millions of actors. The government is taking a much more direct role not only in regulation, but in credit decisions and the actual running of banks, credit companies, auto companies, and soon, the insurance industry. More and more, the fate of companies will ride not only on management's ability to respond to its consumers' needs, but also on decisions made in Washington. Not only will the analyst have to read tea leaves to guess the direction those decisions will take, but he will also have to judge management's ability to do so. This is going to make political analysis as important as economic and financial analysis, and it's going to make guessing the moods of a couple of dozen lawmakers as important as understanding a company's supply chain. And you thought it was only the technical analysts who practiced black magic.

May 22, 2009

Now It's Municipal Bonds

The financial wizards who brought us the mortgage debacle now want to do the same for municipal bonds: One piece of legislation would provide the Federal Reserve with the

authority to fund new liquidity facilities for some municipal

securities. Another would provide federal re-insurance for municipal

bonds, which seeks to make it easier to for municipalities to issue

municipal debt to raise money.

...

House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank, D-Mass.,

defended legislation to create a federal re-insurer, arguing that the

marketplace imposes unfairly high interest rates on municipal bonds,

which typically have a lower rate of default than corporate bonds

"We need to have the safety of municipal bonds reflected in the

interest payments on those bonds," Frank said. "The market plays a very

important role but market failure is also a factor."

Well, he'd know about market failures, having helped create the last one. What he wouldn't know, wouldn't have any idea about, is what the proper interest rate premiums are for municipal debt. If Mr. Frank thinks that municipal debt is a bargain, he's always free to buy some. Why doesn't he just suggest securitizing such debt and chartering companies to buy the securities?

There are already companies that insure municipal debt, so there are two, mutually-reinforcing markets already at work here. If he really thinks that these companies are under-capitalized, there are plenty of regulatory remedies already available. In fact, there's excellent reason to think that what's really going on here is an attempt to bail out California without having to tell people that's what you're doing. Because they might not like that.

May 20, 2009

You Call This Capitalism?

If there's one thing that Ayn Rand and Albert Jay Nock both understood, it's that businessmen will cut deals with the government when they think it's to their advantage. Economics may be the sea that business swims in, but if you need to buy off Ahab with a couple of the slower-moving whales well, hey, who asked them to be your calves? The problem comes when business develops a sort of Stockholm Syndrome about the process, convincing itself - or trying to convince itself - that the presence of the whalers is actually a good thing, even as the herd gets thinner and thinner, the calves somehow never call and never write, and the cow down at the other end of the sand bar needs more and more plankton to get her in the mood. That's the attitude on display by private equity fund mogul Scott Sperling's apologia in yesterday's Wall Street Journal (" Obama's Auto Plan Is Capitalism at Work"). Wrong on both strategy and tactics, is Mr. Sperling.

The Chrysler creditors are not bad or unpatriotic people. They are appropriately acting as good fiduciaries to their investors. But luckily for American citizens, the Obama administration is also acting appropriately by insisting it will only invest taxpayer dollars if the investment has a chance of succeeding. While the government was willing to pay a significant premium to the debtholders to avoid the "friction" costs that occur in a bankruptcy, the administration was not about to do anything stupid with our money.

There's almost nothing right with this paragraph. In fact, the President did call the bondholders bad and unpatriotic. Maybe some bondholders did bid up the

price hoping for a government bailout of their own. A nasty lesson in

the dangers of arbitrary power may be valuable, but it's hardly,

"capitalism." And what of those who didn't, who merely priced in their

place in line, free of public hectoring by the President?

There's nothing "capitalist" about the federal government going into partnership with the ruling party's major constituency. Barring such partnership, there's no reason for it to care about bankruptcy's "friction" costs. Sperling has no idea - none - whether the bondholders got a premium or not. And while the government's new-found fiduciary conscience it touching, it would be more credible if it had shown up sometime before Obama Partners, ULC. contracted to double the national debt in four years.

Means matter. If they didn't,

we wouldn't have a Constitution that theoretically forbids this kind of

neo-feudal behavior by Washington. Even if, every time, the government managed to magically reproduce or improve on what the market or

bankruptcy courts would have done, having a deus Obamica show up and bruit things about this way is extremely dangerous. This

is one reason I'm a Burkean conservative. The bankruptcy laws have evolved over decades both to

give order to the system, but also to embody a reasonably good way of

sorting out competing interests. No politician, or set of politicians is going, time after time, to do better than the

accumulated wisdom of hundreds of thousands.

The self-deception that believes the lie

I wish I were in love again

Lorenz Hart, "I Wish I Were in Love Again," Babes in Arms

Mr. Sperling is a heavy, heavy Democratic contributor. He's is in the business of brokering deals. Why do I suspect the Mr. Sperling (and his partner, Thomas H. Lee) sleep well at night knowing - or at least, hoping - that it's unlikely that government's going to step in and rewrite their terms of their arrangements. Beware, Mr. Sperling, many others have been rudely disabused of similar notions. In the past, he and his company have refused to accept modified terms that didn't suit them. We'd hear a different story if the government were a major investor in his latest fund, and started throwing its weight around to pick and choose his investments. After all, we know how Tom Lauria reacted.

May 15, 2009

A Day Late, A Billion Dollars Short - Maybe

After forcibly nationalizing the banks in all but name, redistributing ownership of GM and Chrysler, and making noises about the necessity of absorbing GMAC, speculation was that the insurance companies are next.

And sure enough, today, the government announced that it was freeing up $22,000,000,000 for insurers who had applied for TARP funds back when they were supposed to be used for buying up toxic assets.

Now, having seen what happens to cities that make deals with the Empire companies that make deals with this administration, at least two of the insurance companies are putting the money down and backing away from the table, while two more are likely to do so. Prudential and Ameriprise are expected to say, thanks but no thanks, and Allstate and Principle are also looking at the money like a side-dish they hadn't ordered, although, of course, they had. Only Hartford and Lincoln(!) seem willing to take the cash.

It's hard to blame the reluctant four, as they have seen banks refused the opportunity to repay their, "loans," contracts broken, officers fired, budgets rewritten, and now talk of salaries being determined in DC. We now know that banks and their officers were threatened with audits, and pension funds and other bondholders with public "shaming," a la the AIG employees who stayed on to wind down the derivatives division. (No such fate seems to attach to any employee of Fannie or Freddie, but that's a subject for another day.)

That two companies are giving into temptation is might disappointing, but hardly surprising, as companies almost never keep a united front against government plans, whatever they may be. And I suspect that we haven't heard the last of this yet. The Obama Administration will almost certainly try to threaten and browbeat the reluctant insurers into taking the cash, or of finding ways to preference their competitors who do. Hopefully the holdouts will continue to do so.

If so, I know who I'll be using to insure my new Ford, when I need a new car.

May 1, 2009

Business Still Doesn't Get It

One stock that I followed at the brokerage, and which I own a couple of hundred shares of, is called Tetra Tech (TTEK). When I get a chance, I like to listen to conference calls of companies I've done research on. Even if I'm not actively modeling the companies right now, I'll learn something about their business, and usually about how they see the economy. Now, TTEK is heavily dependent on government contracts, getting just under 50% of their net revenue from federal contracts, and another 15% or so from state and local governments. Their main line of business is water projects, and they're also heavily involved in wind power, nuclear, and other alternative energy projects. In fact, they make a good case that their work corresponds with the government's current priorities: And one thing that is very clear to us here is, the clear priority

of this administration and the majority party here in the United States

are to support programs for clean water and water infrastructure,

cleaning the environment and energy efficient buildings and energy

independence while reducing CO2 emissions. And these are the markets

that Tetra Tech is primarily focused on. So when their funding goes up,

we are exactly in the right spot.

While they haven't built stimulus money into their projections, they consider themselves to have a natural advantage when that immedately-necessary, time-critical, urgently-needed cash starts to hit the market sometime in the next century: ...And from our perspective, the firms that will

be the most successful are the ones that have contracts in place today. I have said this before in our previous call but with two and half

months gone by, since the signing of the Recover Act, it is

increasingly important to get this into the economy fast. And the only

way we see to do that is to go first to those as whole contracts.

Fair enough. Except for two things. First, one would thing that with two and a half months gone by, and the money still sitting in Beijing and Shanghai, they would have figured out that maybe getting the money to market isn't the most important thing on the government's mind. Second, if the Chrysler and GM debacles have shown us anything, it's that where this money gets spent, and who gets to see it, is going to be determined by narrow political motives. Period. What's at work here is that too many in the business community don't understand that the game has changed. Used to making deals enforceable by steady rules, they are ill-equipped for an environment where there are no rules and the deals only last as long as the President likes them to. The TARP-entangled banks are learning this to their detriment, as are the GM and Chrysler bond-holders. Soon, Ford will be find it out, when it finds itself forced to compete with union-owned car competitors for lending at government-held banks. Those who say that the commercial credit markets will dry up aren't counting on the federal government forcing the banks to lend, quality of the borrower-be-damned. And I'm afraid that the management of Tetra Tech is using entirely the wrong yardstick to measure how the government dole is going to work in the future.

April 30, 2009

The State Backs Loans

Apparently jealous of the Federal government's ability to distort credit markets, the Colorado legislature has decided to get in on the act. SB-051, which Gov. Ritter signed into law, would extend loans to banks, who would then turn around and loan the money to homeowners and businesses to install solar equipment. The idea is to smooth out the cash flows, eliminating the up-front cost of the system, up to $12,500.

For the homeowner, and especially for the business-owner, for whom the interest and depreciation are deductible, this is a good deal.

For the government and the taxpayer, not so much. There's no fiscal note attached, which means that, in theory, there's no cost to the government. This can't possibly be true, otherwise there would be an obvious arbitrage opportunity for the state. The state can obviously issue debt for lower interest than the banks will lend it out at. The state could do that, split the difference on the interest with the banks.

Why not do this? Because of default risk. You know, people not being able to pay the debt. Which under the terms of the bill will almost always result in subordinated liens against the property, with the taxpayer coming out on the short end of the foreclosure proceedings.

Now, where have we heard this story before?

Because It's Worked So Well In The Past

This, from tomorrow's Wall Street Journal: The program is the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, or

TALF, in which investors are given low-cost loans from the Fed and in

turn use the money to buy securities backed by consumer debt. The loans

in this program are three-year loans and so far have been aimed at car

debt, credit-card debt and other consumer loans. The Fed is preparing

to announce new loans with five-year terms to better match the needs of

investors in commercial-mortgage-backed securities, an effort to boost

that sector. Officials have been reluctant to make such long-term loans, for fear

five-year commitments could hamper the central bank's ability to

withdraw money from the financial system down the road. They have been

looking to design the expansion so the loans are less appealing in

later years. ...

The $700 billion CMBS market has rallied in the past month on hopes

TALF would be used to restart the market. Yields on triple-A CMBS bonds

have fallen to about 10% from 12%, according to Trepp, which tracks

commercial-property debt markets. Bringing down the yields on existing debt is critical to spark new

lending because, as long as investors can buy top-rated CMBS that yield

as much as junk bonds, it would be unprofitable for banks to make new

loans. That is because they would have to offer higher yields to

attract investors, wiping out their profits.

How is this wrong? Let us count the ways. - The government is actively encouraging debt-backed securities in real estate

- This worked so well before that it now finds itself in partnership with the UAW, with Chrysler declaring Chapter 11.

- The credit card experiment was so successful in bringing down card rates that Obama called in the credit card companies to explain to them a) who's in charge now, and b) their rates are too high

- Just because you artificially lower rates by creating demand doesn't mean the investments are any better

- It's inflationary, because it puts money into the system that the Fed can't get out quickly

- They want to limit the benefit in the out-years, making the whole project less attractive to

speculators investors

The last paragraph doesn't make any sense to me. First of all, it's only true if the banks can only make money re-selling the debt. How about, you know, collecting the interest on the original loans? Secondly, if the investors would already rather buy CBMS debt than junk bonds, the rate should already be lower. In fact, bringing down the yields is critical to spark new lending because the borrowers can't afford the rates the banks want to charge. You know, kind of like how some people couldn't afford mortgages.

April 2, 2009

Like They Can Just Print the Money

I'm beginning to think that having put the State Capitol near the Mint was a mistake. I think the Democrats are beginning to think that they can just print their way out of whatever burdens they put on the state.

We found out last month that the Colorado Unemployment Insurance Fund was safe, despite climbing unemployment numbers:

Reforms instituted a generation ago appear poised to keep the system solvent even as other states see their unemployment programs go broke. And work is under way to improve the department's Web site this spring, which should make it more user-friendly and ease the strain on the phone system.

...

In the 1980s, state lawmakers set out to protect the state's Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund -- it is used to pay benefits to people who lose their jobs -- after watching it go broke in a recession.

The result was an additional tax, dubbed a "solvency surcharge," that was designed to kick in whenever the trust fund's balance fell below 0.9 percent of the wages paid in the state. The calculation is made each year on June 30, and in 2004, after three years of recession, the tax kicked in.

The result: Colorado's unemployment trust fund grew to $672 million last fall, just as the latest recession was taking hold. That allayed fears that Colorado could again find its unemployment fund out of money.

...

"It would take a deep recession that went on for several years before we would go insolvent," [Mike Cullen, Colorado's director of unemployment insurance] said.

His assertion is backed up by various scenarios that have been considered, including a moderate or even severe recession, said Alex Hall, the department's chief economist.

"Certainly with all the information we have available at this time, and what we feel are reasonable scenarios, including scenarios that take us into a pretty deep recession, we feel that the surcharge is providing that stability and revenue for the unemployment insurance trust fund, and that solvency will not be an issue for us," Hall said.

Well, not so fast there, cowboy.

In a state budget outlook delivered week, the Colorado Legislative Council Staff predicted the fund balance "will fall precariously close to insolvency" to just $44 million by June 30, 2010, down from nearly $700 million on June 30 last year.

The Colorado Department of Labor and Employment expects a healthier fund at $187 million on June 30, 2010, but still has concerns, said Mike Rose, chief of statistical programs for the department.

"We also consider it possible that the fund might be marginally solvent at periods in 2010 and 2011," he said Wednesday.

Unemployment insurance payouts are expected to total $834.1 million in the current fiscal year that ends June 30 and stay at that level for another year, according to the council forecast.

In the midst of this, the legislature seems poised to pass HB 1170, which would entitle employees who are locked out - that is, they have jobs but are involved in a labor dispute - to receive unemployment benefits.

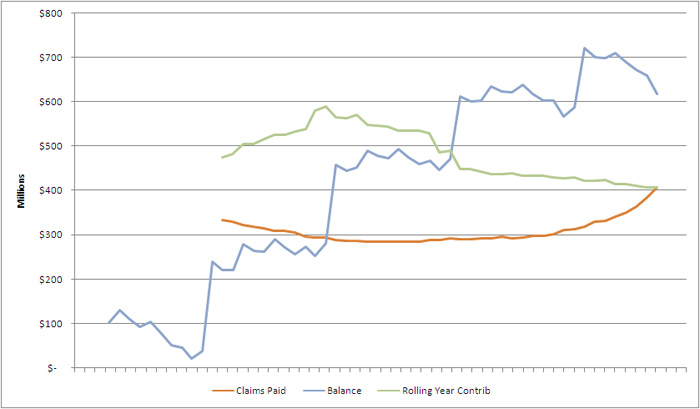

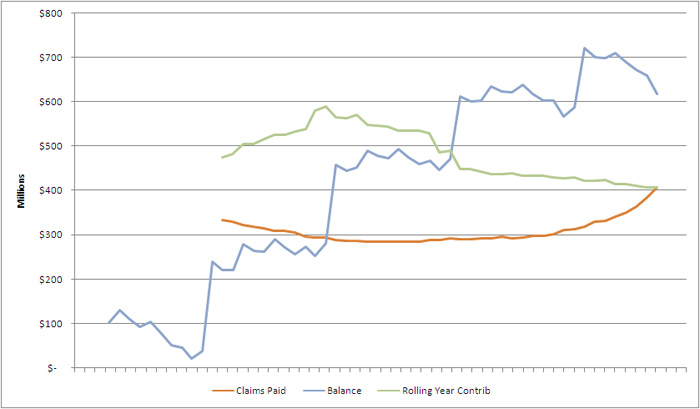

Here's a chart showing the monthly balance of the Colorado Unemployment Insurance Fund, along with a 12-month moving average of employer contributions and benefits paid out:

The reason I've smoothed out these payments and contributions is that employer contributions are extremely seasonal. They generally see a large jump in May, when the surcharge is assessed. They also tend to have almost no contribution during the last month of each quarter, while the first month of each quarter is the highest.

So, the payouts are still rising, and have just passed the contributions. For the first time since the recovery from the last recession, we've seen an actual drop in the fund's balance. Even if all those conveniently-times stories about how we're hitting bottom are correct, unemployment is a trailing indicator. Since contributions are based on the current aggregate salaries paid, that means that contributions will fall even as unemployment rises. This dynamic refills the coffers during the latter part of recoveries and prosperity, but drains them towards the middle and end of recessions.

Then, there's this:

A state Senate committee took up a bill Wednesday that would make Colorado eligible for $127 million in federal stimulus money for the fund by expanding the definition of who can qualify for jobless benefits. It would cost the state an estimated $14.6 million in the fiscal year that begins July 1 to make the changes, largely to pay benefits for newly eligible residents.

So we'll pick up a net $100 million this year, at the cost of no future returns and nobody-bothers-to-ask how much more in perpetual commitments down the line.

The only way out is to float debt. If we end up having to do this during an inflationary period, it'll mean higher rates and even more trouble down the line.

Unemployment insurance is well-established by now. But I can't help wondering if it wouldn't be better to give it to the employees up front rather than paying to the government for what passes for their traditional definition of, "safekeeping"

March 29, 2009

Freddie and Fannie, Together Again

The Wall Street Journal is reporting that the Obama Administration now wants to use Fannie and Freddie as a source of warehouse capital for small mortgage banks. The regulator has asked representatives of mortgage banks, including

the Mortgage Bankers Association, to come up with a detailed plan for

Fannie and Freddie to help mortgage banks get credit. John Courson,

chief executive officer of the association, said in an interview that

the plan should be ready to be presented to the regulator within about

a week. One possibility is that Fannie and Freddie will guarantee debt

issued by warehouse lenders, making it easier for them to provide

financing to mortgage banks. ...

Mortgage

banks typically are small, family-owned companies. Unlike commercial

banks or thrifts, they aren't licensed to take deposits and so don't

have that source of money for their loans. Instead, they borrow money

from warehouse lenders, which often are units of larger banking

companies. The mortgage banks use the short-term credit to provide

loans to their customers and then pay back the warehouse lenders after

selling the loans to bigger banks or to investors such as Fannie or

Freddie. (emphasis added -ed.)

In short, the mortgage banks were one of the prime sources of securitization. Properly done, securitization is a good thing, and if the buyers, rather than the sellers, assess the risks, then there's some chance it could work again. But it's far from clear that the mechanisms are in place for banks to assess these risks. The lack of warehouse capital itself should be a sign that those funders don't believe there are buyers yet for mortgage-backed securities. So, rather than let that market re-develop on a sounder basis, the Obama Administration plans to lend the mortgage banks the money to originate the loans which it then plans to buy itself. The Administration apparently has tired of even trying to conceal the financial shell games it's playing.

March 12, 2009

Bank Sale Rashomon

New Mexico based First States Bank is selling is Colorado banks, known as First Community, to South Dakota-based Great Western Bank, which itself is owned by National Australia Bank. Papers in all three states reported on the sale, but in very different ways. And each tells an important story larger than this sale.

The Las Cruces paper leads with the fact that First States is changing its mind about that TARP money, after all:

Albuquerque-based First State Bancorporation says the sale of its Colorado bank branches will improve its balance sheet enough to eliminate any need to accept federal bailout money.

First State, which does business as First Community Bank, will focus its attention on the New Mexico market, the Albuquerque Journal reported in a copyright story Thursday.

...

Stanford said availability and terms of the federal Troubled Asset Relief Program funding is too uncertain and that First State has withdrawn the application it submitted last October.

The bankers don't like the fact that, increasingly when doing business with the Federal government, a deal really isn't a deal, after all. So rather than get caught in that particular tarp, er, trap, they decided to raise their capitalizatino to 12% from 10% by selling off some of the bad loans.

Both of the Colorado reports, from the DenPo and the Denver Business Journal, mention that it was Bob Beauprez who sold the under-performing banks to First State in the first place. Bad news for an election run this cycle, I'd think.

But neither mentions why Great Western would want to take on this burden. Leave that to the Argus-Leader:

The acquisition involves the purchase of 20 branches and will allow Great Western to expand its small business and agriculture lending, said Jeff Erickson, president and chief executive at Great Western.

"The addition of these Colorado branches is consistent with our strategic growth plans and gives us the opportunity to expand particularly in the areas of small business and agricultural banking," Erickson said.

So it would appear that rather than beg for federal money with Lilliputian-quantity strings attached, a bad sold off an underperforming ball and chain to another bank who saw opportunity there instead.

I can't believe either presidential administration meant for it to work this way, but the raging uncertainly surrounding TARP may be forcing smaller banks to actually let the market operate.

It's Great Time To Raise Taxes

So say a majority of the Metro Mayors Caucus, who want to double the portion of the local RTD sales tax to make sure that the Great White Elephant of a light rail gets built on time and massively over budget.

We can't actually tell which mayors thought that raising taxes in the worst economy since the invention of money was a good idea, and which ones thought they should wait until next year, when all the people who had money to spend were out of work, because neither of the Post's two articles, nor the Caucus's page itself tell you. It's a good thing there are professional journalists around to keep us informed.

They estimate that this glorified Disney monorail is going to suck another $2.2 billion out of the regional economy over the next 8 years. In fact, as has repeatedly been shown, both the cost and revenue forecasts are little better than ouija boards. Denver had no idea well into the 4th quarter of last year how far south its sales tax revenues were headed, and budgeters missed both the commodity price decline of the T-Rex years and the jump in construction prices over the last couple of years.

There's no guarantee that even this amount will be enough, and if mirabile dictu, the thing somehow manages to come in under the excess projected, they'll find some other way to spend the money.

Here's a better idea. Make choices. Like the rest of us.

February 26, 2009

Creating Another Patronage Class

Or, "Taming the Wild Entrepreneur."

From the WSJ's description of the President's tax plan:

As expected, Mr. Obama proposed raising taxes on private-equity fund managers and venture capitalists, by taxing their profits as ordinary income instead of capital gains. That change would raise $23.9 billion over 10 years, according to White House budget office estimates.

I seem to recall the President making some comment in his speech to Congress about helping entrepreneurs. (Maybe I remember it because it was one of the few times where Nancy "Jumping Bean" Pelosi took a brief break from her calisthenics.) Where does the President think entrepreneurs get their capital? Removing this tax break may raise a few billion in the short term, but it removes a key incentive for capital to flow to entrepreneurs in the first place, which means that, like all tax increases, it will ultimately raise far less than projected.

This is self-defeating. Unless, of course, the President wants the government to pick the inventors who'll get the money instead. Almost certainly, he'll claim that he's supporting entrepreneurship by redirecting money into green energy startups. That, combined with his ongoing attack on the oil and coal industries, designed to make green power more competitive by making oil and coal more expensive, will allow him to claim that government investment in just as efficient and effective as private investment.

Of course, it does expand another patronage class, directing creativity where the government wants it to go, with the added satisfaction of making the inventor beg to the government for support.

As for the private-equity funds, those are the funds that have the most flexibility and creativity. Obviously, we'd want to punish them, as well. Stock appreciation is no less a capital gain when one of those funds sees the benefit, than when yours or my 401(k) or IRA sees it, but the President wants to treat them differently, because most private equity investors are successful and prosperous.

One last note. On Tuesday night, the President said that, "if you earn less than $250,000, your taxes won't go up one dime." Turns out he wasn't talking to individuals, but to married couples. If you live in the northeast, it's pretty common for each spouse to bring home $125,000 apiece, and it doesn't go all that far.

We really have elected a cross between FDR and Wesley Mouch.

January 9, 2009

When All 8.5%'s Aren't The Same

PERA likes to claims that there's no immediate threat to the long-term health of its retirement fund, despite the fact that as of October, it counted its liabilities as 60% funded. Part of this claim rests on the assumption of long-term 8,5% returns, and that there's plenty of time to make up the difference.

While 8.5% return isn't unreasonable, this ignores two factors that in isolation don't make much difference, but in combination can lead to wildly varying results.

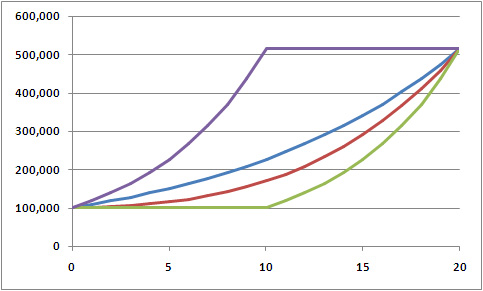

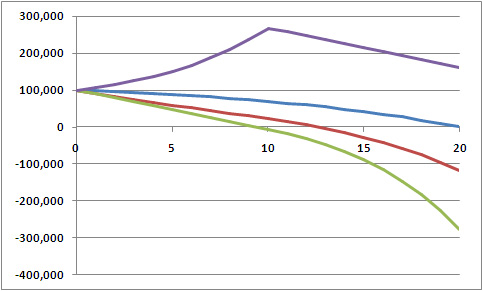

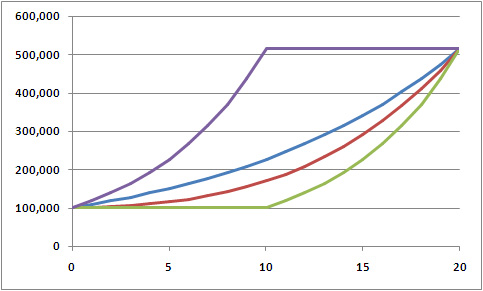

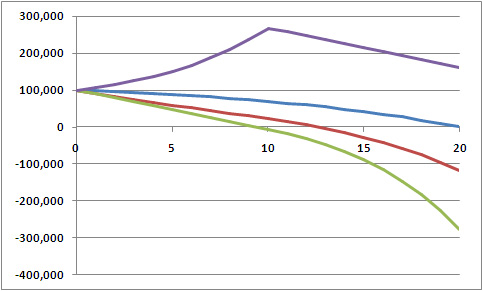

First, many different distributions of returns can, over time, lead to the same average annual return:

The blue curve is a simple, constant 8.5% return. The other curves represent different annual returns over time, resulting in the same ending balance, and thus the same average annual return of 8.5%.

Second, PERA has obligations, and it has to pay those obligations every year, drawing down the principal. Let's now add on a constant annual payment:

The blue line returns to $0, meaning that an 8.5% return funds the 20-year obligations 100%. But look at the other curves. The more the returns are delayed, the more the principal has been drawn down beforehand.

These are highly simplified assumptions, of course. The incoming administration is likely to pursue policies that will depress markets for years by increasing uncertainty, making it harder to make up the deficit at the end. So I'd discount PERA's assertions of long-term solvency fairly steeply.

December 12, 2008

Bad Markets Mask Problems, Too

Hank Paulson, and now the British, are complaining that the bailout money available to the banks isn't being lent. So why not? Well, it's not because banks are happy to sit on fat piles of cash while you and I look for work. And it's not, contrary to some conspiratorial emails I've gotten, because the bank want to own everything from the GM to your house. Banks make money by lending. They don't make money by being in the real estate business, or the car business, or any other business other than lending. They want to be able to judge good managers of those businesses, but they neither have nor want the skills to run those businesses themselves. So why aren't they lending? It's because they can't find anyone they want to lend to. They won't lend to other banks because they can't tell which banks are sound and which aren't. But most of their business comes from lending to businesses, and right now, it's almost impossible to tell which businesses have good stories and which don't. I spoke which a friend of mine who invests money for a living. He's a value investor, and a good one, and his complaint was that every company had one of two stories: it wouldn't make it, or it had a great model for when the economy turned around. The valuation measures he uses - that most value investors use - aren't distinguishing between merely good companies and companies actually worth investing in. It means that almost every company's story is now the macro story, the story of the larger economy, not its own. And it means that the market, the individual decisions that individual investors make about individual companies, is being driven by the uncertainty in that macro picture. The sooner we let the market find a bottom, the sooner we let the economy adjust, the sooner those valuation measures will begin to make sense again, and the sooner we can start turning this thing around. Or, Obama can take all that FDR talk seriously, and we can be having the same discussion 7 years from now.

December 10, 2008

Rebuilding the House of Cards

With its Treasury assets low, the Fed is considering issuing its own debt, something it's never done before, and may be prohibited by law from doing. The central bank has seen its balance sheet more than double, to over $2 trillion, and is trying to come up with added flexibility. This is a spectacularly bad idea, so I'd expect to see enabling legislation on the President's desk by next week. Anyone who buys Fed debt would be basically buying all those risky assets - plus whatever new risky assets the Fed decides to backstop tomorrow. The market doesn't think much of those securities, which is why the Fed had to step in and buy them in the first place. On the open market, they'd have insanely high yields and minimal value. What the Fed is proposing to do is to remarket those securities, in effect as CDOs without the tranches, rebuilding the house of cards that got us into this problem in the first place. Any difference between the yield those securities would be required to pay on the open market and the interest rate the Fed would have to pay would be - totally and completely - based on the public's confidence in the US Government's ability to cover those costs. In other words, you and me. There are also almost certainly conflicts of interest (so to speak) between the Fed's role as a stabilizer of the debt markets and its role as a participant in them. It's one reason the Fed has been independent, with the ability to tighten money and drive up borrowing costs largely without interference from the Treasury. The Fed as debtor may be much less willing to fight inflation.

December 3, 2008

Denver Debt

This past election, Denver voters passed a school bond initiative worth almost half a billion dollars, the only locality to pass its bond initiative. There's a reason places De-Bruce, but there's also a reason that it's a terrible idea to do so. Now Dave Ballmer of Douglas County is probably one of the smartest guys in the State House, and he's pointed out that if you can borrow low, it's better to do that and lock in a low interest rate for the long-term. The problem is that right now may not be the best time to borrow low. At the moment, Denver's not exactly swimming in debt, but it also doesn't have a huge amount of flexibility there. According to the 2008 Approved Budget, the city will spend $361 million in debt service, most of which ($274 million) is for DIA bonds. That's from total net expenditures of about $2.1 billion, for just under 17% of spending. That's more than was on the books for capital expenditures - $272 million. However, Denver's already facing a $7 million shortfall this year. That may not sound like much, but it will assuredly be larger next year. Denver will have to float that debt, which by definition is general obligation debt and not revenue bonds.

We have some idea of what the market might pay. The Bond Buyer Muni Index which measures the prices paid for municipal bonds. It's off 19% from its high 2 years ago, and the average yield is now 6.16%, well up from its 52-week low of 4.72%. But consider this: yesterday the NY/NJ Port Authority got no takers at auction. Hell of a time to take on another $500,000,000 in debt, huh?

November 28, 2008

Newspaper Finance - II

The Balance Sheet

Put simply, American newspaper companies have too much debt, and have been fooling themsevles about how much equity they have. When they went through that period of consolidation a few years back, the surviving (so far) companies vastly overpaid for the properties they bought, thinking that either they could turn them around or that the names would translate into sales. Then they borrowed agains these "assets," and have thus robbed themselves of whatever flexibility they had.

Here are the assets of the seven companies we've been looking at so far:

The bars represent the total assets. The blue represents something called, "Goodwill," the red, everything else. Goodwill is, roughly speaking, the vigorish that you pay for a company. Essentially, according to accounting rules, you're not allowed to pay more for something than it's worth. What you pay for it is what it's worth. So if you pay $4 million for a company whose net assets are valued at $3 million, after the buyout you put down the extra $1 million as an asset called, "Goodwill." It can generously be interpreted as extra cash you think the property should generate over time.

But it's a guess, an estimation, and can also serve as a slush line item to hide the fact that you just overpaid by 50% for a name that isn't generating any ad revenue any more, but that People Trust. It used to be that Goodwill was amortized over a period of time. Now, it has to be re-examined as often as necessary, and written down as appropriate.

Let's take a look at what's going to happen, as accountants realize that if the New York Times can't sell ad space, neither will the Podunk Press they sunk $2.5 extra large into five years ago, and that all the Goodwill in the world isn't going to change the fact that Iowans are getting their news from here and their local advertising from here.

The other rule here, so basic it's been known since the Italian Renaissance as the Accounting Rule is that Assets = Liabilities + Equity. If I write down an asset, I also need to subtract a like amount from either liabilities or equity. Since Goodwill isn't exactly a loan, likely it'll come out of equity. Here are the Owners' Equity lines from these companies, before and after Goodwill is subtracted:

That's right, boys and girls. Four of these Titans of Type go from having positive equity to negative equity, meaning they owe more than their companies are worth. And this is a completely defensible assessment. Given the current market, and the likelihood of how these will develop, you can't sell that Goodwill on the open market, because people apparently have resorted to paying what things are worth.

Now all of these companies have some long-term debt, although the Washington Post company seems to have made an effort to pay its down to minimal levels. Typically, I don't want debt-to-equity to be more than about 1. I know, there was a time not so very long ago when investors liked leverage. Because after all, we'd always be able to refinance that, wouldn't we? But I was never comfortable with huge debt-equity ratios.

Naturally, the D-E are calculating including Goodwill. Here's what happens when you subtract the Goodwill from the equity, and recalculate:

Not much fun. Of course, four of them go from positive to negative, including USA Today, which looked safe. The Journal newspapers only edge up to 1.30, and the NY Times - whoa, there, Pinch! - run up from a safe-looking 0.75 to almost 3.2. Only the Washington Post manages to stay sober.

These companies have been fooling themselves about the state of their balance sheets, believing that they had better balance than they did, because they were counting on revenues that will never materialize.

Now, I know what you're thinking. Debt's ok if you can pay it. Well, as we'll see next time, that's a problem, too.

November 3, 2008

Pollsters as Research Analysts

Over at Jim Geraghty's Campaign Spot at National Review Online, his mentor, alias Obi Wan, has this to say about the turnout models the pollsters are using, turnout models which very heavily favor Democrats:

Look, the real drama to this election is being provided not by the candidates but the polling community. By which I mean the decision they made to stake out — as Campaign Spot has noted — a remarkably bold position, that the Democratic Party turnout is not only going to exceed a recent historic advantage of 4 percent but go to 6.5 percent (Rasmussen) to 8 percent in many polls to even 12 percent in one.

I keep looking for the justification for this. Not easy to find. Rather like the academics' one-time belief in the Aristotlean spheres and an earth-centered universe, it just seems to be a pretty good working theory — some sort of way to make sense of observable phenomena and keep all the smart people talking agreeably and pleasantly among themselves.

This is remarkably similar to what happens when stock analysts all use multipels to value companies. Investors make decisions based on these valuations. In a rising market, the tendency is to push up the price of the lowest-valued stock. Also, sell-side analysts have an incentive to find reasons to raise their price targets. Once a security becomes, "fairly priced," the stock won't appreciate very quickly, and investors will be looking for new values to invest in.

It's only when the analysts, who have been looking mostly at each other, start looking at actual underlying value, and realize that they've effectively priced in the next century's and a half's worth of earnings, that the price falls. Quickly.

I would submit that there's an excellent chance that the models the analysts are using are over-pricing Obama. If the correction comes, of course, it'll come all at once.

November 2, 2008

PERA-lous Waters

In case you needed another reason to vote for someone who's got a financial, rather than a political, background, you got one this week.

The largest pension fund for state and local public employees lost $10 billion in market value through mid-October, raising the specter of higher contribution rates or lower benefits in coming years if markets don't improve rapidly.

Colorado PERA, which covers 413,000 employees and retirees, saw its assets plummet from $41 billion at the beginning of the year to $31 billion on Oct. 15. That drop was not as severe as some market benchmarks, but it comes on top of a long-term underfunding problem that the Public Employees' Retirement Association had hoped to make up in part through investment gains.

PERA officials have tried to reassure state and local employees that their current benefits are not at risk and that the pension has plenty of cash to weather month-to-month market fluctuations. They said they have no current plans to ask the PERA board or the legislature for changes in contributions or benefits, but the legislature did adjust those levels in 2006 for long-term solvency.

PERA's formula for a 30-year return to full funding depends on an average annual gain of 8.5 percent from its investments.

"Obviously we've got a bit of a bigger hole now," said PERA executive director Meredith Williams.

Gee, ya think? 8.5% Isn't an unreasonable number; the average stock market rise has been 8% over the last 90 years. But they're also invested in bonds, real estate, and overseas markets, and alternative investments.

Some of the T-bond investments - intended not for bond appreciation but for steady income - will have to be rolled over in the next year or two. They'll yield a lot less, which will also have to be made up. Now maybe there's a way of selling off the higher-yielding bonds now, but only if you see higher yields in which to invest.

PERA's going to have a hard time meeting all the promises it's made. Heaven help us if we start making more.

October 10, 2008

Special BTR Today

I'll be doing a special noon-time BTR show today about the financial crisis with King Banaian of SCSU Scholars, and William Polley of, ah, William Polley.

Hopefully, we'll all learn something.

Confession for Financial Regulators & Bankers

We have privatized profit and socialized loss;

We have over-regulated S&Ls;

We have demanded loans to people who can't pay;

We have mortgaged with low down-payments;

We have subsidized debt rather than down payments;

We have substituted credit scores for judgment;

We have masked risk with "insurance;"

We have used government to subsidize systemic risk;

For all these, forgive us, pardon us, grant us another bankroll to try again.

Best. Description. Ever

For those of you trying to figure out how the mortgage market evolved into this over-articulated dinosaur-like critical-care patient, Russ Roberts and and Arnold Kling trace the history from pre-Depression era mortgage markets to today. It's brilliant, detailed, and understandable to the layman.

And a little depressing as regards to the future.

Listen to the whole thing.

September 18, 2008

The Monetary Crunch - Act III

The monetarists have been hard on the Fed. But understanding why the Fed screwed up 8 years ago or ever 4 years ago is different from understanding what it's trying to do now.

First, everyone go back and re-read (or re-watch) Milton Friedman's explanation of the Great Depression in Free to Choose. Then read remarks by the-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke on the subject. (For dessert, read this article by Princeton professor Ben Bernanke arguing that central bankers shouldn't move interest rates in order to affect stock prices.)

Now with your homework done, we're ready to discuss this stuff, er, rationally. Remember that the monetary aspects of the Great Contraction were essentially a three-act play. In 1928, the Fed, led by NY Governor Ben Strong, left out the punch bowl by keeping rates low. By 1929, the Fed had tightened policy, and was bursting the stock market bubble. But by 1931, the Fed, in a misguided attempt to keep the country on the gold standard, raised interest rates again, furthering the contraction. (A paper by then-Princeton economist Ben Bernanke shows that countries' recoveries were a direct result of going off gold and reflating.)

So here we are in the early 2000s. Act I - Greenspan leaves out the punchbowl, possibly partly in response to the withering criticism he incurred in 1996-1997 when he tapped the brakes. Act II - Bernanke begins to tighten incrementally, not so much to bust the bubble as to bring it down gently. Whether such a thing is possible remains an open question.

What Bernanke is desperately trying to do is to avoid a repeat of Act III. He's not trying to prop up stock prices, though access to credit markets will have that effect. He is trying to prevent another Great Contraction, where nobody lends to anyone else, and the underlying economy suffers mightily. And anyone who thinks that anything else is going on here simply doesn't know what he's talking about.

It's possible that this will work, and it's possible that it won't. Certainly the Fed has been pursuing this policy for over a year now, and the financial crisis has rolled on to clobber bigger and bigger institutions. It may well be that administering the medicine while the patient is still contagious simply won't work. It may be that the risk of moral hazard creates more problems than it solves. And it may be that - with LIBOR jumping up this morning - the credit markets will seize up, anyway.

None of this means that what the Fed is doing now is the right - or the wrong - thing. It is to say that it's trying to do something different from what it did 80 years ago, and maybe we ought to at least be pleased about that.

March 10, 2008

Sen. Salazar on Mortgages

U.S. Senator Ken Salazar seems to believe that you can create wealth by moving it around, so it's only fitting that the current Democratic leadership would put him on the Finance Committee.

The Senator's office sent out a press release about the mortgage problem, and the legislation he's backing to "solve" the "crisis."

The housing crisis has hit Colorado especially hard. The rising number of foreclosures have had a direct impact on home values in the state; according the Case-Shiller home price index, housing prices in the Denver area are down 5 percent from their peak in August 2006, and further declines may be on the horizon. In 2007, Colorado ranked 5th in the nation in foreclosures and in Colorado in 2007 foreclosures were up 30 percent over 2006 and 140 percent over 2005. During September of last year, 1 in every 376 houses in Colorado was in some stage of foreclosure.

The same Case-Shiller Index shows prices down only 1.8% year-over-year, with inventory on the market among the lowest in the country, and barely any increase in inventory. It's almost impossible to interpret these numbers: 5th in foreclosure rate, or 5th in number of houses? Certainly more than doubling the number of foreclosures isn't good; but given that the number of houses owned has increased considerably since 2005, an increase of the foreclosure rate to less than 0.3% of homes from about 0.2% in 2005 is hardly cause for panic.

. The National Association of Home Builders estimates that, in 2002, 6.77% of Colorado’s Gross State Product (GSP) was directly accountable to home building, and another 12.71% was accountable to housing services, for a total housing contribution of 19.48% of GSP.

Let's stipulate that the NAHB has an incentive to pump that number up as high as possible. Let's also recall that from 2002 to 2003, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, construction fell from 6.33% of Colorado's GDP to 5.79%, yet there was little if any actual panic then. Given that the actual recession was over by late 2001, it's fair to characterize housing activity as dependent on broader credit markets, and that it's a trailing industry.

In fact, the problems in the credit markets may have started with subprime mortgages, but have since spread far beyond them. Given that, most of the proposed, "help" is worse than useless. It's closing the barn door after the horses have already hopped a freight train and are designing silks for the races at Aqueduct. Other bits constitute a shell game. And a few make some sense, but those are the ones that belie most Democratic rhetoric about taxes and business.

Increase pre-foreclosure counseling funds ($200 million) - This additional funding will help housing counselors continue their outreach to families at risk of foreclosure. These added funds should assist as many as 500,000 additional families connect with their mortgage servicer or lender to explore options that will keep them in their homes.

Probably a worthy endeavor. Certainly not the Federal government's job. And you can bet that the non-profit recipients of this "aid" will suddenly find themselves bound by all sorts of equal-protection rules that they had never considered. And doesn't $4000 per family seem like a lot of money? At a very generous $100/hour, that's a week's worth of work per family.

Allow Housing Finance Agencies (HFAs) to Issue Bonds for Refinancings (increase current cap by $10 billion) - This provision will allow housing finance agencies to use proceeds from mortgage revenue bonds to refinance subprime loans...

So they're going to refinance subprime loans with mortgage revenue bonds. But the underlying loan isn't a better risk just because the Federal government is refinancing it. If, as with most FHA loans, the Federal government is guaranteeing the loan, the family may get a better rate, and it may have a better chance of staying in the house. But FHA default rates are significantly higher than mortgages overall. There's no particular reason to think that this is much more than throwing good money after bad.

Change Bankruptcy Code to Allow Judge to Modify Mortgage of Debtor - This title could help more than 600,000 financially-troubled families keep their homes by allowing them to modify their mortgages in bankruptcy. It eliminates a provision of the bankruptcy law that prohibits modifications to mortgage loans on the debtor’s principal residence for homeowners who meet strict income and expense criteria. With this change, primary mortgages are treated the same as vacation homes and family farms.

Again, this is basically taking money from the lender and giving it to the borrower. Note that this isn't a renegotiation of the terms between the borrower and the lender. It's a condition imposed on the lender by a judge. The potential for socio-financial engineering here by activist bankruptcy judges should be apparent. And it keeps houses off the market, artificially supporting prices. If we are headed into a recession, or even a plod-along economy, it's only going to keep houses out of the hands of people who could otherwise afford them.

CDBG Money for Purchase and Rehab of Foreclosed Properties ($4 billion) - Homes that have been foreclosed and are sitting unoccupied on the market can sap neighboring homes of their value. This provision allows localities with the highest foreclosure numbers and rates access CDBG funds to use toward purchasing these properties, rehabilitate them if necessary and rent or re-sell them. Productive occupancy of foreclosed homes will help stimulate economic activity and help prevent further loss of home equity in struggling neighborhoods.

Why are these houses a better investment for municipalities than for auction bidders?

Net Operating Loss Carry Back from Finance Stimulus Package - For companies losing money in this economic downturn, this proposal extends a provision that allows corporations to apply (or “carry back”) their net operating losses to tax returns from prior years in which they were profitable, and receive any applicable tax refunds. Under current law, companies are allowed to carry their losses back only two years – this proposal would extend that period to five years for losses incurred in 2006, 2007, and 2008, effectively allowing companies to average out their good years and their bad years for tax purposes. This is particularly helpful for “boom-and-bust” industries such as the home construction industry.

This proposal actually makes some sense. It would be nice to see Democrats apply it to other cyclical industries. Oil and gas are classic boom-and-bust industries, and they've grown from 1% of Colorado's economy in 1999 to 5.5% in 2006. But the Senator never misses a chance to hobble their in-state development through regulation and EPA actions.

On the other hand, loss carry-forwards are usually intended to help startup companies and companies and rapidly expanding industries. Housing was never conceived of as a growth industry, and probably wouldn't have been without the financial innovation that made it possible. Tech companies didn't get this sort of help in 2001, and it's possible that this sort of tax break will encourage over-investment, and actually help produce the sort of bubbles we're working through now.

Simplified Disclosure on Mortgages Documents -This provision would amend the Truth-in-Lending Act and improve the loan disclosures given to homebuyers not only when they apply for a home purchase loan, but also when they refinance their home. The measure would require: (i) firm disclosure of the terms of the mortgage loan within 3 days of application (and not later than 7 days before closing); and (ii) the maximum loan payment be disclosed, not only at application, but also seven days before closing. Finally, this provision would clarify that lenders are subject to statutory damages for violations of Truth-in-Lending disclosure provisions and increase the damages for mortgage violations.

This provision also makes sense. A free market needs to be an informed market. If your maximum payment turns out to be several times your current income, maybe you ought to think about putting away a little more for a down payment and going conventional. Then, too, maybe the mortgage lender will look at that number, and stop putting people with $90,000 incomes into $500,000 homes.

So there you have it. One-and-a-half provisions that make sense. A lot of other money shifting economic risk onto...you.

January 31, 2008

Vindicated!

As many of you know, I don't think much of the rigid investing style boxes that Morningstar has done so much to promote. They probably cost investors hundreds of basis points per year in returns (and therefore cost the market considerable sums as a result of inefficiencies). They also cost the government millions in enforcement, to make sure that when someone says, "Large-Cap Value" they mean "Large-Cap Value," even though nobody can agree on what "Large" and "Value" mean.

So imagine my surprise when I saw this in the very first reading of the CFA Level II Statistical Methods section:

Style Analysis Correlations

...For the 20 years ending in 2002, the correlation between the monthly returns to the Russell 2000 Growth Index and the Russell 2000 Value Index was 0.8526.

...Because the returns to the two indexes are highly correlated, we can say that very little difference exists between the two return series, and therefore, we may not be able to justify distinguishing between small-cap growth and small-cap value as different investment styles.

Heh.

January 23, 2008

CFA Level I

Level I: Pass

For several weeks, the CFA Institute had been emailing me, telling that Scores Will Be Available OnLine on January 23, 2008, at 9:00 AM ET.

And so, Sunday, just as Tynes lined up to take that fateful kick, the monks loaded up the oxcarts, securing the last of the packages for their trip back down the road the Charlottesville.

Now, when you log in, the page is dominated by a large ASCII text table, breaking down your results into 9 categories and 3 results, <50%, 50-70%, and >70%, and they expect you, at bleary-hundred hours, to see and interpret the difference between this: - and this: *. Hmmm, that looks like a lot of these: *, over in the >70% column...

And then, just when you're asking yourself, "So do I get to the next Level, or was I slain by the troll hiding around the corner?" you see, not in big flashing neon red, but in dark, understated, color-scheme compliant blue, the letters:

Level I: Pass

This is a good thing. This exam represented a considerable investment in time and money over the last 6 months, and the soccer-like pace of the grading didn't add to the anticipation so much as deaden it. In fact, all those "*"s over on the right were correct. The only subjects on which I didn't pass individually were Derivatives and Alternative Assets, so naturally I'll spend the next five months obsessing over those, wonder where, oh where I could have gone wrong.

Five months? Yes, because that's when the Level II exam is.

August 28, 2007

Receivables Securitization II

Naturally, the first company I look at isn't publicly traded. Land O'Lakes is a cooperative, with widely-held shares, but whose 10-Q states that it's not publicly traded and it ain't gonna be. You want to hold shares? Become a farmer.

Naturally, they're also an example of the right way to securitize receivables. They maintain a $200 million credit line, secured at a floating LIBOR+87.5 basis points. Their receivables are 50% above that at $300 million in the last period, They list it under outstanding debt, and currently have no balance. Eagle Materials (EXP) used much the same mechanism, although they closed out their facility in 2006.

Why is this the right way? Well, receivables are an asset, so in theory, there's nothing the matter with selling them. But when you become dependent on getting that cash early, so much so that you're willing to pay interest to get it, you put yourself doubly at risk during a downturn. You won't have as many receivables to collect, and you'll probably have to pay a higher rate to get them. And remember, this is operating cash flow, boys.

By turning it into a line of credit, it's apparent ahead of time when you're dipping into it, and it's going to show up as a financing cash flow.

Now, I need to find guys doing it the wrong way.

August 27, 2007

Receivables Securitization

Over at the Three-Letter Monte, the CFA Blog, I have a posting discussing securitization of accounts receivables, and its location within the Statement of Cash Flows. I'm not sure this is a particularly widespread problem, but it may well be a more serious one for certain companies.

Here's the issue. Some companies have gotten into the habit of packaging their receivables and selling them off at some discount to a buyer. You know those ads where Orson Bean asks you why you should have to wait for a settlement or a lottery annuity? Well these companies apparently feel the same way. So they collect the money now from a third party, buy their hambuger, and then pay the third party back next Tuesday when their customers pay them.

Typically, companies will publish a schedule of their receivables, if not how long they're outstanding, then how long they expect them to be. This gives the purchaser some idea of the historical collections record, how long they can expect to take to collect what's outstanding, and how much they might expect to have to write off.

The buyer could take an annuity, some percentage of the receivables over time, or some percentage at the beginning. Any of these arrangements can be considered borrowing at some interest rate. As a result, they should be listed on the statement of cash flows under financing cash flows. But because the revenue is secured by receivables, which are part of operating cash flows, many companies categorize them there.

Now, the notional interest rates some of these companies pay will rise, if they can find buyers at all. Their operating cash flows will shrink, and valuations based on those cash flows will fall substantially. In fact, there's reason to suspect that those companies that place this financing under operations are the ones that are most likely to need the cash.

Next step: find a list of such companies.

August 17, 2007

Subprime Subpar

The Wall Street Journal carried a page-1 case study of a family with a subprime problem (subscription required). The whole thing is terribly sad. People possibly losing their home and businessmen losing their investments. Commenters at the site, on other stories, who've casually thrown out that people who default probably shouldn't have been in their homes in the first place are right, but miss the point. These people could have continued to rent and build savings. Instead, they're liable to lose both their homes and everything they've paid into them. You don't have to advocate some sort of massive bailout in order to feel sorry for them.

This, though, caught my eye:

The price was a major stretch at $567,000. But the couple, who had sold a home a few years earlier to move to a better area, was tired of renting. Mr. and Mrs. Montes convened a meeting with their two teenage daughters around the kitchen table to hash out the implications. "We agreed we wanted to be homeowners again," says Mr. Montes, "even if it meant the end of vacations and not eating out as often."

Like many people who jumped into the rising housing market in recent years, they had little money for a down payment and chose a loan that would hold their monthly payments down for the first two years, then "reset" to a much higher level. Mr. and Mrs. Montes say their mortgage broker assured them they would be able to refinance in a couple of years to keep their payments affordable.

...

Until recently, the Montes family didn't seem like the type that would find itself faced with foreclosure. They live in a solid neighborhood and are both employed and in good health. "My wife and I make pretty good money," says Mr. Montes. Mrs. Montes works as a school secretary. Together, they earned nearly $90,000 last year.

A family of four qualified for a $550,000 mortgage on a $90,000 income? Good freaking grief. Now, read that second paragraph again: "Mr. and Mrs. Montes say their mortgage broker assured them they would be able to refinance in a couple of years to keep their payments affordable."

Someone put these people into a loan they knew they wouldn't be able to afford. This is the kind of behavior that leads people to think that the whole system is crooked. People who behave this way deserve to lose their investment.

But they told them they wouldn't be able to afford it. And the couple were rightly nervous about it. This was no starry-eyed couple trying to make ends meet with help from Mom and Dad. This was a couple who had been around long enough to know that things change.

I was nervous about paying for a $215,000 FHA mortgage on that much income seven years ago. Yes, it was 30-yr fixed (since refinanced down a couple of times), but it was predictable, and since the government was co-signing, the interest rate was pretty good. I was told that, since the rule of thumb was House = 3 x Salary, there was plenty of room. I also consoled myself with the knowledge that they wouldn't lend me the money if I couldn't pay it back. There was a reason for every flaming hoop I had to jump through. Look, nothing's guaranteed, and I've made my share of bad investments. But there's also investment and then there's roulette.

Now, for worse for now, for better eventually, there is no such comfort. People are perfectly willing to loan you money they know you can't pay back, and to tell you that, and to count on your signing, anyway. They we willing to do this because nobody in that room, except the buyer, was going to have to live with that loan for very long. The seller gets paid, the real estate agents gets his commission, and the loan company sells the loan to someone else. The reason mortgage rates are higher now is that there aren't any buyers, which means that the mortgage brokers are either charging higher interest or playing with (gasp) their own money. And the reason so many of them went under is because they suddenly found themselves with a bunch of loans they couldn't re-sell, which put a serious crimp into their cash flow.

You need to walk in with a calculator and CFP and a budget. You need to know what your tax bracket is and how much of that mortgage interest you'll be seeing come back each April. And for God's sake don't take a mortgage that you need to escape to be able to afford. Because at the end of the day, you are still signing a piece of paper, and it's your responsibility to know what the hell you're signing up for.

July 30, 2007

CFA Blog

I mean it this time. After a couple of fits and starts, I'm going to take the Level I exam in December, and I'm going to be blogging about the studying.

A few starter posts to get things going...

November 29, 2006

Wednesday Morning

Snow. Cold. When they gang up on you, the roads turn into skating rinks. For the first time, I had to use the 4WD just tooling around town. Of course, the Jeep is rear-wheel drive normally, not front-wheel as I'm used to, but even 4WD doesn't help your braking all that much. It just means that you slide straight. The snow's still coming down even now, but tomorrow's supposed to be sunny, so perhaps there will be photo-ops anew.

So having finished the NASD licensing steeplechase, and not yet having renewed the Quest for the CFA, I've got a little time on my hands in the evenings, and I've decided that at least one of the adult ed classes at the shul must be for me. Last night I tried out the beginning Talmud class - the nth beginning Talmud class I've tried - and it went pretty well.

Business-halachah-legal geekery follows immediately.

We're learning Tractate Makkot, and it deals in part with the penalties for perjury in civil cases. The basic rule is that if you lie under oath as a witness, and if that lie would have cost someone money, you owe that person damages equal to what you tried to cost them. So if you falsely claim that someone stole $1000, and that lie is uncovered and the claim denied, you owe the accused $1000, since that's what you tried to do him out of.

Apply this to a loan. You claim that Bob borrowed $1000 for 30 days and now needs to pay it back. Bob claims the loan was for 10 years. What would your lie have cost him? Not $1000, since everyone agrees that he needs to pay that back anyway.

In fact, you'd owe Bob what he would have been willing to pay to have the money for 10 years, minus what he'd be willing to pay to have it for 30 days. I'm not sure how they would have calculated this back in 200 CE, but nowadays, you'd just apply the short-term and long-term interest rates to determine the value of having the money on hand. (There are halachic issues with charging interest, but set those aside for the moment.) In short, the raabis understood, at least at some level, the notion of opportunity cost and the time value of money.

Pretty neat, huh?

Less neat is this week-old piece from the Denver Post about minority enrollment at CU. Since this is a report about a report (a Boorstinian pseudo-event of the first order), objections to the diagnosis and prescriptions are anticipated and dismissed:

The study accused flagship universities of blaming their low diversity on inadequate state funding and the K-12 system.

Instead, they should direct more financial aid to low-income students, recruit minority students more aggressively and focus on helping minority students succeed in college, the report said.

Unasked by the reporter or by the CU administration: of the Colorado high school graduates who qualify as "minorities" under their definition, how many can actually read at 12-grade levels, and why is it CU's job to remediate this problem?

September 27, 2006

Tradesports Arbitrage

Has Tradesports internally mispriced the chance of the Democrats retaking the Senate? That is, do the chances of the Dems winning the individual races they need "add up" to the same number as the chances of them winning back the chamber as a whole? Mind you, this is an entirely difference question from whether or not Tradesports has accurately priced the contracts. I'm only looking at whether or not Tradesports is internally consistent with itself.

(I'm not the first one to think about this. A Google search turned up this somewhat amateurish attempt, along with these more sophisticated ones.)

Tradesports is a futures market based on real-world events. If you buy a contract, you pay, say $0.56 for a contract stating that the Republicans will hold the House. If they do, the contract expires with a value of $1.00, and you make $0.19. If Speaker Bela Pelosi is sworn in on Jan. 1, then the contract, like promises to control spending and defend the country, expire worthless, and you lose your $0.81. Ideally, the sum of the prices on a given event should equal 1. And the prices of equivalent events should equal each other. If they don't then an arbitrage opportunity exists, which means free money, which means drinks for everyone.

For instance, if the contract giving control to the Republicans is selling for $0.49, and the contract giving control to the Democrats is selling for $0.49, then you only have to pay $0.98 to buy one of each, kind of like what business is doing.

As for the notion of equivalent events, here's a simple example made complex. Suppose I can bet on two flips of a coin. I can bet on each flip by itself, and I can bet on the end result of both flips. In the real world, there's a 50% chance of getting heads, a 50% chance of getting tails, and a 25% chance of getting tails both times. So the prices of the contracts for tails on the first flip = 0.50, tails on the second flip = 0.50, and tails both times, 0.25. Betting the two tails separately is the same event as betting the two tails together.