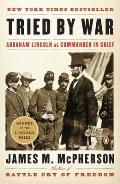

by James McPherson

by James McPherson

On this, the 200th Anniversary of perhaps our greatest President – I’m still holding out for Washington, but perhaps that’s on the basis of his entire body of work – it’s worth considering his role as Commander-in-Chief. Not merely as described in Eliot Cohen’s leadership study, Supreme Command, but his role specificallly in shaping policy, strategy, and operations. Other Presidents have had to fill that role, although none under such critical circumstances as Lincoln.

James McPherson, who is rapidly becoming one of our finest popular Civil War historians, published his Tried By War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief last year. In it, he follows the progress of Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief, first trying to save the Union by preventing the war, then trying to win it as expeditiously as possible. The progress of the war itself is almost background, the battles and campaigns making cameo appearances in support of the main story – Lincoln’s conduct of command.

Much of the anecdotal material is well-known: Lincoln’s depressions after defeats, his constamt urgings of McClellan and other generals to press forward, and his exultation after the victories at Atlanta and Richmond.

What McPherson adds is structure. About 20 years ago, Edward Luttwak famously created levels of strategy – grand strategy, strategy, theatre-level strategy, and tactics. McPherson does something similar, defining five interconnected levels in which Lincoln – indeed, all commanders-in-chief – must operate: National Policy, National Strategy, Military Strategy, Military Operations, and Military Tactics. Lincoln worked in all five, although we typically remember him more for his hectoring his general in the area of military operations.

What McPherson remembers, and what Lincoln never lost sight of, is that war is also a political activity. From the outset, he set a National Policy – the preservation of the union. All else was to support that Policy, starting with National Strategy. At first, the best strategy was to ignore slavery as an issue. Later, as the war stretched on, and Southern Unionist sentiment failed to manifest itself, National Strategy changed to the liberation of the slaves and a more aggressive military posture.

Lincoln, almost before many of his generals, realized that military operations would have to be coordinated in time, to offset the South’s advantage of interior lines of operation. And at the tactical level, he supported the purchase of the repeating rifle, and the eventual jettisonning of the cumbersome supply trains which slowed down Union advances.

McPherson also dwells on the political management of the war, especially during the critical election year of 1864. We all know that McClellan captured the Democratic nomination on a peace platform, from which he immediately began to pull back. Union sentiment swung back and forth, wildly over-reacting to both victories and setbacks, fanned by an equally voluble press.

Advances early in the year were tempered by defeats and stalls on both fronts, and by Jubal Early’s attack on Washington from the rear. We think of the Lincoln-Grant relationship as rock-solid, but McPherson points out that:

Neither Lincoln nor Grant could have been in a good mood when they met on July 31 for a discussion that lasted five hours. No record was made of their conversation. Lincoln may have come as close as he ever did to chewing out Grant for all the failures that had occurred during the past six weeks.

Copperheads in the North were promoting reunion without victory, while the Southern leadership was selling the peace as a means to independence, after all. “The publicity surrounding these peace overtures should have put to rest the Copperhead argument that the nation could have peace and reunion without military victory. But it did not.”

EvenafterAtlanta and Richmond, Lincoln understood that public opinion could be lost. We tend to forget how vital Sheridan’s campaign in the Shennandoah and George Thomas’s defeat of Hood in Tennessee were to sealing the final victory.

And in a further reminder that the more things change, the more they stay the same:

Union captives in Southern prison camps could not vote in the presidential election, of course, but most other soldiers could. By 1864 all Northern states except the three whose legislatures were controlled by Democrats – Illinois, Indiana, and New Jersey – had provided for soldiers to cast absentee ballots. Those three exceptions seemed to indicate that Democrats knew quite well which way most soldiers would vote.

Moat of these reminders and surprises come in the last 75 pages of the book. But the whole thing is well worth reading. And a reminder that a successful wartime President needs to be involved in all aspects of the conduct of the war. That it really is too imporant to be left to the generals.