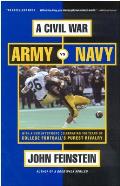

by John Feinstein

by John Feinstein

When Charlie Weatherbie arrived to take up his first head coaching position, he was asked about Army-Navy. He’d seen other rivalries, he said. He knew about other rivalries, Oklahoma-Oklahoma State, for instance. Seemed no different to him. People at Navy spent way too much time worrying about Army when there was a whole season to play.

A subtitle to the Navy side might be “The Education of Charlie Weatherbie.” Even going into the game, after Army Week and a whole season of “Beat Army,” he was more focused on the winning season than on Beating Army. At the end of the game, Weatherbie broke down in tears, repeatedly apologizing to his players for a critical coaching mistake that probably cost them the game, taking responsibility in the best Academy tradition.

Talk about a transformative experience.

Army and Navy have been playing each other in football for 100 years, they’ve been fighting wars together for over 200. What Weatherbie didn’t understand – what most people don’t understand – is that while the Academies live to beat each other in football, they respect rather than hate each other. They save that for the Air Force, the kid brother who thinks it’s about winning games.

The book is 10 years old by now, and the football programs have changed a little. In 1995, both academies had programs on the rocks. Army had a respectable program, but Navy had suffered through a couple of 1-win seasons. Both schools were in the lower tier of Division I-A, and were regularly scheduling I-AA teams to pad their win totals. Bowl games were fond, distant memories. Since, while Army’s coaching has completely fallen apart, Navy has gone on to several bowl games and has recently dominated the series.

The Naval Academy was also suffering through a series of scandals – an Electrical Engineering cheating scandal, alumni involved in a murder-suicide, and three midshipmen killed in a freak car accident returning to the Yard. Army had won the previous three games by a total of five points, leaving this as the last chance for Navy’s graduating firstclassmen to win The Game. A popular superintendent had reluctantly returned to Annapolis at the end of his career to right a ship gone horribly wrong.

While West Point as a whole didn’t need the win as badly as Navy did, their coach probably did. And the Army football team didn’t lack for compelling characters with compelling stories. Often these reflect the harsh and somewhat anachronistic discipline that the Academies impose on their underclassmen. One of the best concerns Army team captain Cantelupe and Beast, the introductory hazing new plebes go through the summer that the enter West Point:

Like every plebe, Cantelupe hated Beast, although his approach to it was a little different than most. Cantelupe takes the things that are important to him very seriously: his family, his friends, his responsibilities, and his football. Beyond that, he sees most things in life as not being worth too much concern.

…

Cantelupe did what he had to do when it came to corps discipline. But he always did it with enough humor to keep himself sane. On one of the first nights of Beast, the first classman in charge of his squad sat everyone down after dinner and demanded that they tell him their family’s origins.

“Klein,” he demanded, looking at Derek Klein, “What kind of name is that?”

“Sir, it’s German sir,” Klein barked back.

“O’Grady,” the firstie continued, “What kind of name is that?”

“Sir, Irish sir.”

It continued like that until the firstie reached Cantelupe, who was both bored and bemused by the whole exercise.

“Cantelupe,” the first roared, “What kind of a name is that?”

“Sir,” Cantelupe replied, his face as straight and serious as everyone else’s, “it’s produce sir.”

The firstie stared at Cantelupe in disbelief. Everyone else stared at the floor, praying they wouldn’t burst into laughter. Klein was biting his lip so hard he thought it must surely b bleeding.

“Do you think that’s funny, Cantelupe?” the firstie screamed. He then gave Cantelupe several minutes of haranguing on what happened to wise-ass plebes who didn’t take their superior officers seriously.

If Feinstein has a problem, it’s that there are too many good stories, with too many good personalities. Guys who have to work their way through Academy prep school to make it in. Guys who fail out. And the ever-present tension between the Corps or the Brigade as a whole, and the football team’s special privileges.

He’s covering the story of two teams through a whole year, and it’s hard to make the narrative hang together. While Feinstein nominally tells the story through Cantelupe and Navy’s captain Andrew Thompson, they provide more of a common thread than a consistent point of view. Also, as the above passage indicates, his praise for his editor is somewhat misplaced.

That said, it was probably a mistake for me to read this book in August.

I already can’t wait for the last weekend in November.