Archive for category Finance

Individuals Pay Corporate Taxes – Just Not Always The Consumer

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Finance, PPC, Taxes on July 26th, 2011

Right now, our corporate tax structure makes no sense. It not only plays favorites, it drives many of the unfavored abroad. We have the highest corporate tax rate in the world, and the code is so riddled with exceptions, subsidies, and loopholes, disguised as “incentives,” that, as Megan McArdle put it, large companies basically have branch offices of the IRS on site to negotiate their tax bills.

So it makes sense that we should lower the corporate tax rate in exchange for cleaning the thing up.

It makes sense for all sorts of reasons, but not for one reason you often hear mentioned: that corporations just pass the increase along to consumers. They don’t. At least not always, because they can’t.

Who pays the tax is known as, “tax incidence,” and it depends on who has the fewest options. Economics recognizes something called, “elasticity.” Supply Elasticity is how much the supply changes depending on the price, and if you’ve been following along, you’ll know that Demand Elasticity is how much demand changes in response to price changes. Vacation rentals have a pretty high demand elasticity. Gasoline, on the other hand, has a fairly low demand elasticity: the price goes up, but you still have to get to work.

On the supply side, airline seats have a fairly low supply elasticity; once an airline has planes in inventory, they’re not likely to mothball them, at least not in the short run. Tobacco, on the other hand, has a pretty high supply elasticity: when the price falls, supply falls quickly to match.

(A word for the pedantic: elasticity is not constant. At very high or low price levels, we as consumers or producers may behave differently. You can only drive so much, even at $1 a gallon, lowering demand elasticity. Of course, at that price, there won’t be any refineries operating, either. Also, there’s the economist’s eternal escape hatch – the long-run and the short-run. It may be expensive for me to increase or limit supply, but give me enough time, and I’ll find a way.)

So what does this have to do with the tax on eggs in China?

If I’m the one with fewer choices, I’ll probably have to eat most of the tax. Suppose, for example, I make the Indispensible Widget. It’s easy for me to ramp up and ramp down production, but it’s a commodity you have to have, every day, all the time. This gives me, as a producer, pricing power, and it means that when our taxes get raised, we can pretty much – up to a point – pass that expense along to you. (Remember, even monopolies don’t have infinite pricing power, and even commodities producers have competition.) So in that case, yes, it’s the consumer who gets shafted.

Now, suppose I sell something else, something where the industry can’t readily reduce supply, but you have a lot a choice in whether or not buy. High-end vacation hotel rooms, for instance. I may be able to reduce some operating costs, but those costs are what make them luxury. And vacations are very price-sensitive. There may be some times when I can just tack on the tax, but if I’m trying to compete with your staycation, I probably won’t. My shareholders and employees will eat it.

Note that there’s a similar relationship at work with how shareholders and employees split their end of the deal, too. Labor, too, has supply and demand price elasticity. If your labor is a commodity, you may not get that raise this year, or may even get a pay cut or fired. If you have specialized skills, ownership may not be able to pass the tax along to you, either.

The point here is that while individuals always pay corporate taxes, those individuals may be consumers, employees, or owners, depending on the business. It’s not as simple as businesses just passing the cost on to their customers.

Why is this an argument for tax reform? Hayek’s Pretense of Knowledge. The government can’t really know, except in the coarsest way, what the tax incidence for the corporate income tax will be on a given industry. Subsidies may end up going to industries that don’t need them, or that can’t find a good place to invest them. They may reward employees, or not; they may help subsidize demand, or not. And what was true yesterday may well not be true tomorrow.

Ideally, we would simply ditch the corporate income tax altogether. Salaries and employment would rise, as would consumption, dividends, and investment, so the government would see a lot of that revenue come back immediately, and much more from growth.

But barring that, a flat rate, which instead of aiming for universal “fairness” accepts the fact that industries and businesses differ from one another, is the wisest course.

Greeks Bearing Grifts

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Economics, Finance, PPC, Regulation on June 16th, 2011

And if the threat of starvation and a southern land rush weren’t enough here on Disaster Wednesday, there’s always Greece:

…But conditions in European markets are deteriorating. The main risk from Greece has always been contagion, and that process is already under way.

Most directly, prices of Portuguese and Irish bonds have fallen sharply, with 10-year yields rising above 11% and the cost of insuring their debt at record levels. The gap between Spanish and German 10-year bond yields is at its widest since January. The market is effectively giving no credit for any reforms or budget policies set out in the past six months.

The next link in the chain, the banking system, has been affected. In Spain, progress by banks on regaining market access has gone into reverse: Average borrowing from the European Central Bank jumped to €53 billion ($76.32 billion) in May from €42 billion in April.

Meanwhile, the contagion into core banks may be being underestimated by investors. Moody’s on Tuesday said it could downgrade France’s BNP Paribas, Société Générale and Crédit Agricole due to their holdings of Greek debt, and the ratings firm is looking at whether other banks could face similar risks.

Disturbingly, the worries have now reached non-financial companies, which have been virtually bulletproof this year. Investment-grade bond issuance has come to a near-standstill.

I seem to remember having seen this movie before, as the prequel to to 2008’s Episode IV: A New Hope. It may provide some cold comfort to Americans that this time, it’s taking place in Austrian, even if Germany’s pending LBO of the rest of Europe isn’t the Teutonic Shift the President had in mind a couple of weeks ago.

But there’s no particular reason to be complacent. Just as we’ve managed to convert our economy from fast-falling to encased-in-amber stasis, we could be in for another financial shock. Megan McArdle suggests one route: (I hate to quote a post in almost its entirety, but it’s short, and I don’t think I can say it better)

During the wave of banking regulation that followed the Great Depression, the government slapped heavy controls on the interest rates that banks could offer. They weren’t very good, which made the banks sounder, and consumers worse off. When inflation and interest rates rose in the late sixties, this became a big problem. Then some clever chap came up with the money market fund. Legally it worked like an investment fund, not a bank account: you invested in shares, with each share priced at a dollar. The fund invested in the commercial paper market and committed to keep each share worth exactly one dollar; whatever investment return they got was paid out as interest on your shares. This gave you something that looked a lot like a bank account, without all the legal tsuris.

In 2008, it turns out that these money market accounts were–as was always pretty obvious–a lot more like bank accounts than mutual fund shares. The Reserve Primary fund held a lot of Lehmann Brothers commercial paper, which plunged close to zero, meaning that there were no longer enough assets in the fund to make all the shares worth at least a dollar. This is known as “breaking the buck”, and it was not the first time it had happened. But it was the first time in more than a decade that it had happened at a fund which didn’t have enough money to top up the assets in the fund to bring them back to a value of $1. Bigger investment houses had been quietly topping up their money market funds for month, but Reserve Primary was a smaller firm, and they didn’t have the spare cash handy.This triggered a run on the money markets, which the government really only stopped by a) passing TARP and b) guaranteeing money market funds. But as Matt Yglesias points out, Dodd-Frank stripped Treasury of the authority to do such a thing again. And now the money markets are exposed to a Greek default.

Something like 45% of US Money Market funds have some direct exposure to Greek debt. Greece defaults, and many of these funds may be breaking the buck without Big Ben backstopping for them.

But that’s only the direct exposure. Then, there’s the indirect exposure, though insurance, and (probably) Credit Default Swaps:

Finally, it’s worth noting that once you account for the substantial payouts that US agents will have to make to European creditors in the case of a default by one of the PIGs, financial institutions in the US have roughly as much to lose from default as those in France and Germany. (See the figures in blue in the table above.) The apparent eagerness of US banks and insurance companies to sell default insurance to European creditors means that they will now have to substantially share in the pain inflicted by a PIG default.

The risk to US banks itself may be small, but the effects of having sold this insurance, and of people finding out that they sold this insurance, could be substantial:

The big US banks are well-capitalized now, and can fairly easily absorb losses of several billions of dollars in the event of a Greek default. But two serious concerns remain. First, I fear that this may have the potential consequence of exacerbating the flight to safety that will happen in the event of Greece’s default; if you have no idea who is really going to be on the hook and ultimately liable for CDS payments, your best strategy may be to trust no one. I don’t think that triggering post-traumatic flashbacks of the fall of 2008 is going to do good things to the market or the economy. Second, I wonder if there’s a public relations disaster just lying in wait for the big US banks. After all, how will you feel (assuming you don’t work on Wall Street) when you read the headline that Big Bank X lost money because it sold billions of dollars of credit default insurance while it was on taxpayer life-support? Rightly or wrongly, I’m guessing that Big Bank X will not be very popular for a while.

This also doesn’t address the US banks’ exposure to the European banks, the ones that may go under when Greece finally decides to call it quits. They may have positive exposure to those banks, and find that holdings in them, or loans to them, are suddenly less liquid than they had hoped.

There’s one other issue that I haven’t see addressed anywhere, and that’s the question of securitized Greek debt. Remember that we thought the subprime crisis could be “contained,” because subprime mortgages were such a small portion of the overall mortgage market, never mind the credit markets as a whole. Then it turned out that the subprime assets were poisoning entire classes of securities, since they were so highly leveraged. Is it possible – and this is purely speculation, I really do not know the answer to this – it is possible that people have done the same thing with sovereign debt, and that there are CDOs out there with Greek debt incorporated into them? Securities that could suddenly default, even though they only contain a small mix of drachmas in there?

Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff point out that after every financial crisis, governments find themselves with significantly higher debt, as they seek to stop the dominoes from falling. The potential exists for European governments to become dominoes themselves, and if McArdle is right, there’s some risk (probably small, but hard to say how much) that won’t even be able to step in again and keep our own house in order.

More Pension Risk

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Business, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on May 29th, 2011

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that pensions are moving more money back into hedge funds:

Also, pension officials are using the historically strong returns of hedge funds to justify a rosier future outlook for their investment returns. By generating more gains from their investments, pension funds can avoid the politically unpalatable position of having to raise more money via higher taxes or bigger contributions from employees or reducing benefits for the current or future retirees.

The Fire & Police Pension Association of Colorado, which manages roughly $3.5 billion, now has 11% of its portfolio allocated to hedge funds after having no cash invested in these funds at the start of the year.

…

While pensions have been investing in private equity and what are called alternative investments for many years, hedge funds have represented a smaller part of their portfolio. The average hedge-fund allocation among public pensions has increased to 6.8% this year, from 6.5% for 2010 and 3.6% in 2007, according to data-tracker Preqin. (Emphasis added.)

PERA’s own investments in hedge funds are unclear from the latest data, but if the “Other of Other” category is representative, it could be about 10% of their holdings.

This may be good in the short run. There’s no doubt that some of these funds have done well, being able to hedge some of their risk away and focus on capturing industry or sector returns. But there are some serious dangers here, and they are complicated by the problems already noted with pension accounting.

First, there’s no such thing as risk-free alpha. Remember, the market tries to match risk with return. If someone is selling an investment with 10% return and the risk associated with equities, beware. Because if that were possible over the long run, enough people would pull money from equities and pile it into this mythical investment, so the returns would match. Either that, or there’s hidden risk in there that justifies the extra return.

Either way, in the long run, the funds are taking on more risk, or will have the additional return arbitraged away as more people invest in these strategies. Also, if many of the funds are using the same strategy, it may be difficult for them to execute trades that actually allow them to limit risk, as they may all be trying to sell overperformers, or buy hedges, at the same time.

Another threat to pension funds is in the bolded sentence above. Managers are not only using these returns to justify higher projected returns. What goes unstated is that they’ll also use them to justify the higher discount rates, that make their pensions look better-funded than they are. It’s a perfect example of the perverse accounting incentives built into fund management.

Last, these strategies are not necessarily transparent, making it difficult for independent auditors to even assess the risk that these pensions are taking on.

I’m all for finding ways to hedge away risk, and there’s no reason that pension funds can’t participate in some of those techniques. I’m skeptical that, in the absence of fixing the underlying problems, this approach is going to do any more than paper over problems, yet again.

Everybody Likes A Good Discount

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Economics, Finance, PERA, PPC on April 24th, 2011

So with all the discussion about PERA, one key aspect of pension accounting hasn’t yet been mentioned: the discount rate. Now before you go all accounting-comatose on me, understand how important this is. Because with all the talk of how underfunded PERA is, it’s actually even more underfunded than you think.

Basically, if you have an obligation to meet, the discount rate is the rate you use to see how much money you need to have now in order to meet that obligation. So if you’re going to have to make good on a $100,000 obligation 10 years from now, and you use a 4.5% discount rate, you need to have about $65,000 now. If you use an 8% discount rate, you only need about $46,000.

Of course, the discount rate isn’t arbitrary. It represents a concept. The discount rate is the required rate of return, the return that an investor in that project requires, given the level of risk that he’s taking on.

The problem here, and how this relates to PERA (and many, many other public pensions), is that PERA is using the wrong discount rate. Instead of using the 4.5% discount rate, they’re using the 8% discount rate, which makes them look even less underfunded than they are.

Discount That Optimism

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Colorado Politics, Finance, PERA on July 28th, 2010

On Sunday night’s Backbone Business, we discussed the problems with (mostly) public pensions. PERA, Colorado’s Public Employee Retirement Administration, is not exempt from these issues.

The biggest issue with public pensions is that, for some reason, they’re allowed to game the number that describes how much money they need to have in hand in order to cover future expenses.

We should always discount future cash flows according to the required rate of return of the project. In this case, the project, a government guarantee, should be discounted at the same rate as comparable government bonds. Corporate pensions, a company guarantee, discount at a rate equivalent to a basket of highly-rated corporate bonds, since that closely matches their obligation.

The economic reason for this is that a lower interest rate is associated with lower risk. If you discount at a lower rate, it implies a higher level of safety, and therefore, creates an obligation to have more money on hand to cover those expenses. Since the level of risk associated with a state pension is the same as the level of risk associated with a government bond, they should be discounted at the same rate. Otherwise you have equivalent risks paying different returns which creates all sorts of arbitrage opportunities.

The problem is that government pensions are allowed to discount at the expected rate of return of their investments, in effect presenting a risky investment as though it were a sound one, and therefore underfunding the plan.

Currently, PERA takes full advantage of this loophole, and discounts its obligations at 8%, the expected return on its investments. Needless to say, despite whatever reforms were passed in the last session, it’s not enough, and the taxpayers are going to be left holding the bag.

Eventually, we are going to have to transition to a defined contribution plan, and with the unfunded obligation growing rather than shrinking, the sooner we make that decision, the less painful it will be.

Financial “Reform”

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Finance on June 25th, 2010

According to the Wall Street Journal:

…Banks [will be allowed] to trade interest-rate swaps, certain credit derivatives and others—in other words the kind of standard safeguards a bank would take to hedge its own risk.

Banks, however, would have to set up separately capitalized affiliates to trade derivatives in areas lawmakers perceived as riskier, including metals, energy swaps, and agriculture commodities, among other things.

At one level, this makes sense. Banks can use the markets to hedge risk, but would set up separately capitalized companies to speculate. But that isn’t what the article says, and it’s not clear that’s what legislators have in mind. And it shows they still don’t understand the problem.

Classifying tradeable derivates on the basis of how lawmakers perceive their risk is like classifying road repairs based on how lawmakers perceive the sturdiness of the bridge. Al Franken probably drove back and forth across the I-35 bridge all the time, never guessing that it was unsound, and I can guarantee you he knows even less about what constitutes a “risky” derivative.

I still think the proper distinction here is between hedged and unhedged risk. If the bank is sitting in the middle between two sets of counter-parties, it’s at considerably less risk than if it’s speculating on a directional move, or if it could get killed by a large directional move.

The other derivative legislation largely mirrors what Eric Janszen talked about on the Bubble show:

Would for the first time extend comprehensive regulation to the over-the-counter derivatives market, including the trading of the products and the companies that sell them. Would require many routine derivatives to be traded on exchanges and routed through clearinghouses. Customized swaps could still be traded over-the-counter, but they would have to be reported to central repositories so regulators could get a broader picture of what’s going on in the market. Would impose new capital, margin, reporting, record-keeping and business conduct rules on firms that deal in derivatives.

This is a big change, and pardon me if I doubt the ability of regulators to actually understand what’s going on in the market in any way that lets them steer clear of crisis. But on the whole, more transparency is better. I am given to understand, however, that the exchanges, which are nominally supposed to adopt the underwriting risk of the contracts, would themselves be backstopped by the government. So much for ending “too big to fail.”

Cross-posted on Backbone Business.

UPDATE: Additional thoughts here.

German Shorts

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Business, Finance on May 18th, 2010

No, not liederhosen.

The German government has announced that it will ban short-selling of 10 major financial institutions, government debt, and CDSs on government debt. It roughly parallels our three-week ban on short-selling about 800 financials in the fall of 2008, and is likely to be about as effective, pretty much like all short-selling bans throughout history.

It’s already had the effect of appearing more like panic than prudence, driving the Euro down over a penny against the Dollar today, since the announcement, and probably increasing short interest today in all three areas it seeks to shore up.

Short-sellers, as apparently has to be endlessly repeated, provide liquidity and more information to the market than the long side alone can provide. The fact that this action will have to go to the options market for satisfaction is likely to increase transaction costs. It may reduce naked short-selling, but it will also similarly increase transaction costs for those who are merely hedging, as well.

Similarly, it’s like to decrease the liquidity for Euro-zone government debt, raising interest rates; probably not the effect that the Germans are looking for here. And remember, being short the CDS means being the counter-party for someone who’s looking to parcel out some of the risk, which takes even more liquidity off the table.

Good move, Germany.

Inflation and Gold

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Economics, Finance on April 18th, 2010

Gold fanatics are of the opinion that the gold markets are predicting a massive run-up in inflation. Their policy responses run from abandoning the Fed, to establishing competing currencies, to establishing gold as legal tender for debts, and are not mutually exclusive. The problem is, the debt markets tell another story.

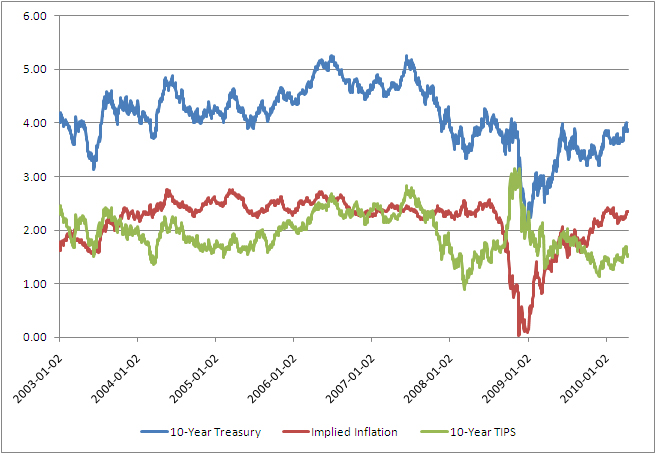

Since 2003, the US Treasury has offered 10-year TIPS, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, bills whose coupons is linked to inflation. At a fairly simplistic level, but an internally consistent one, you can subtract the TIPS rate from the nominal 10-year Treasury rate to see how the markets are pricing 10-year inflation:

As you can see, from mid 2003 until late 2008, the market pretty consistently priced inflation at about 2.5%, and that’s about where it was most of the time. Then, in late 2008, the world came to and end, and with the 2nd Great Contraction, the TIPS rate jumped up to the nominal rate, indicating that inflation was the least of anyone’s concern. The last 16 months have seen a gradual return to historical averages for inflation. But even as nominal rates have risen, the TIPS rates have kept pace, and the current implied inflation, 2.33% is at or slightly below historical averages.

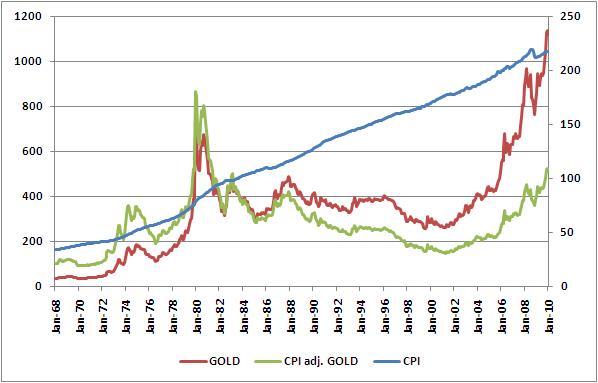

Compare this to gold over the last few decades. Here’s just over 40 years’ worth of gold price info: the current price, the CPI-adjusted price, and the CPI (1982=100):

So much for gold as an infallible inflation hedge. From 1983, prices march inexorably upwards, but I’ll wait until 2010 for the real price of gold to come back. The quadrupling of gold’s real price from 1970 to 1975 doesn’t seem justified by the CPI, and while there’s a definite bump in the CPI in 1980, again, it doesn’t seem to justify gold’s move from $200 to $800. Then, even as there’s another little bump in 1990, gold prices continue down.

Gold is a commodity, with its own price dynamic. Fear can drive up the price, and people move to safety. But gold can also be its own bubble, with inflation being the justification rather than the cause. Like any other commodity, there’s supply and demand. Gold bugs tend to focus on demand. But…

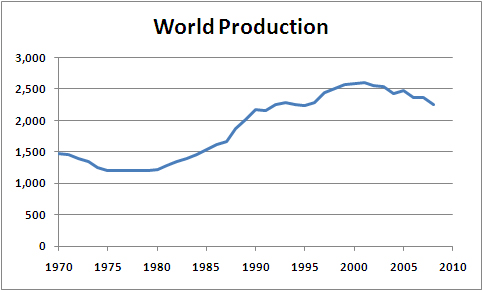

This is the world production of gold according to the USGS. Now, we’ve seen declines in the production of gold before, so perhaps this isn’t “Peak Gold.” In the early 1970s, coinciding with the run-up in prices from ’72-’75. After 1980, production picks up in response to the bubble, and continues to rise until 1990 or so. And then, from 1996 until 2010, production and price are almost inverse to each other.

If this is Peak Gold, if new veins aren’t as productive, and worldwide production will continue to fall, then that goes a long way towards explaining the recent run-up.

This doesn’t mean that inflation won’t happen, or that all’s right with the world. The massive pile-up in federal debt is the sort of thing monetary catastrophe is made of. And once a loss of confidence occurs, it usually happens more swiftly than imagined, even by most who expect it. The credit markets can, and do, miss signals. Perhaps they’re pricing in a higher likelihood of either default or punitive tax rates to make up for the unbearable entitlements we’ve loaded onto ourselves. Or perhaps, more ominously, they’re just not looking beyond the next couple of years, and since we can’t predict when the bottom falls out, there’s no point in trying.

But gold bugs can’t pick and choose signals, and right now, the credit markets just aren’t signaling, “Weimar 1923.” A comprehensive theory has to encompass all the data. The simplest answer is that the run-up in gold isn’t very much about inflation, but about simple supply and demand, with supply falling as much as demand picking up.

PERA Nears A Deal – UPDATED

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Budget, Colorado Politics, Finance, PERA on January 8th, 2010

The Denver Post is reporting that negotiators are nearing a deal on PERA, the generous defined-benefit plan that most state workers have benefited from over the years:

The major changes to the Public Employees’ Retirement Association include increasing employee and employer contributions by 2 percent and reducing cost-of-living increases for current retirees from 3.5 percent this year, capping them at 2 percent….

Several issues remain to be resolved, most revolving around age of retirement and years of service needed to get full benefits, but both men said those issues could be resolved by the time lawmakers convene for their 120-day session next week….

So let’s assume that accounting for the government worked the same as accounting for a private pension. In fact, in this case, there’s no good reason why it shouldn’t. Basically, the plan has assets and obligations, but both of those change over time. So the inputs to the model are 1) Actuarial Assessments, and 2) Interest Rate Assessments.

Actuarial assessments include things like Years of Service, Age of Retirement, Years of Benefits, Salary Increases (due to seniority), Benefit Increases (due to age). Interest rate assessments include benefit inflation, health care inflation, discount rate, and return on plan assets.

The things that can be adjusted generally fall into Actuarial Assessments, and that’s where the article focuses. Retirement age and years of service all fall into this category. What’s critical is the stuff that’s left out. We have no idea what the plan’s assumed rate of inflation, discount rate, rate of benefit inflation or health care inflation are, or what the assumed return on investment is. We don’t know what they’ve assumed them to be in the past. If those numbers are unrealistic, or even aggressive, we’ll likely find ourselves right back in the same place a few years from now.

Consider a simple scenario, where the plan assumes a constant 8% real return on plan assets. Historically, this might be reasonable. But if the bulk of the return is in the out years, the plan will have depleted its assets before those returns can catch up, and will run out of money. (Cool graphs on this topic here.) If you could forecast how returns would change over time, you’d have a more accurate model, but the fact is, as we’ve seen time and again, it’s impossible to make those sorts of predicts 5 years out, never mind 25 years out. Which means that the solvency of any defined-benefit plan is mostly guesswork. Promises of long-term solvency are simply mirages.

Maintaining a defined-benefit for incoming and even current employees is not realistic (promises made to those already retired must be honored). The only fair way to move forward is to transition to a defined-contribution plan, which has only assets, and by definitions, no liabilities. Unfortunately, the political will for this move doesn’t seem to exist.

UPDATE: According to the actuarial projections accompanying PERA’s legislative recommendations, they are indeed projecting a constant 8.0% return for the next 30 years. This strikes me as aggressive. But they key point to remember is that these returns are never constant, and that the shape of that returns curve strongly affects the ending balance. There is simply no way for even the best prognosticators to get that right, and worse, no acknowledgment in the docs that it even matters.

Venture Capital, Take Note

Posted by Joshua Sharf in Economics, Finance, Health Care on September 22nd, 2009

In the generally miserable venture capital environment of that last few quarters, one bright spot has been the health sciences market. It’s one of the area where Colorado can compete effectively, and an area where America is well ahead of the rest of the world. It produces actual long-term savings and real quality-of-life and lifespan improvements.

And the Senate – presumably with the agreement of Colorado’s Bennet and Udall – is getting ready to kill it.

First, the numbers. VC itself has, not surprisingly, gone cliff-diving along with the rest of investment capital recently. After the dot-com craziness, total VC investment seemed to return to a normal growth curve this century before crashing in the recent downturn:

The one exception to this has been Life Sciences. While well behind last year’s pace, VC in life sciences has recovered fairly well in Q2, to the average over the last 5 years, and close to 2005 levels:

Note the steep drop-off in Healthcare Services VC after 2000. I’m not certain why that’s so, but it’d be interesting to find out. Also note that medical device investment has grown not only in dollars, but also as a percentage of total LS investment.

While the National Venture Capital Association doesn’t provide crosstabs between regions and sectors, it’s reasonable to assume that at least some of Colorado’s growth from 3.0% of venture capital dollars in 2008 to 4.3% in 2009 is a result of our strong biotech sector.

Now, the Senate is proposing what is, in effect, a national excise tax on medical device sales, to help pay for the health care takeover. (Hat tip: TigerHawk) Exactly where do they think the large companies come from? Exactly where do they think the large companies get their devices to re-sell? They don’t free-ride on this technology, they buy it once the ideas have been developed by smaller, ie, venture firms.

Brilliant idea, gentlemen.